7.2 Evolution of Radio Broadcasting

At its most basic level, radio transmits communication through the use of radio waves. This includes both radio used for person-to-person communication and radio used for mass communication. Although most people associate the term “radio” with radio stations that broadcast to the general public, everything from television to cell phones utilizes radio wave technology, making it a primary conduit for person-to-person communication.

The Invention of Radio

Nathan B. Stubblefield is often cited as an overlooked pioneer in wireless communication, having publicly demonstrated a wireless telephone device as early as 1892 in Murray, Kentucky. His innovative, albeit short-range, technology relied on inductive and conductive methods to transmit voice without wires. While his early work was groundbreaking, his association with the Wireless Telephone Company of America, formed in 1898, proved to be a significant setback. This company was widely regarded as a fraudulent scheme that exploited Stubblefield’s demonstrations to attract investors without delivering a commercially viable product.

Despite his early innovations and the fact that he did secure several patents for his specific wireless communication apparatuses, Stubblefield struggled to achieve widespread recognition or financial success from his inventions. He ultimately died in poverty in 1928 in a primitive dwelling in Kentucky. Although the scientific consensus generally credits others for the development of modern radio based on electromagnetic waves, Stubblefield’s early and compelling demonstrations have led some, particularly in his home state, to advocate for him as the true inventor of radio, highlighting his significant, albeit distinct, contributions to early wireless technology.

Guglielmo Marconi is often credited with inventing the method to harness radio communication. As a young man living in Italy, Marconi read a biography of Heinrich Hertz, who had written and experimented with early forms of wireless transmission. Marconi then duplicated Hertz’s experiments in his own home, successfully sending transmissions from one side of his attic to the other (PBS). He saw the potential for the technology and approached the Italian government for support. When the government showed no interest in his ideas, Marconi moved to England and obtained a patent for his device in 1896. Rather than inventing radio from scratch, however, Marconi essentially combined the ideas and experiments of others to create a valuable communications tool (Coe, 1996).

Long-distance electronic communication has existed since the mid-19th century. The telegraph communicated messages through a series of long and short clicks. Cables across the Atlantic Ocean connected even the far-distant United States and England using this technology. By the 1870s, Alexander Graham Bell used telegraph technology to develop the telephone, which could transmit an individual’s voice over the same cables used by its predecessor.

When Marconi popularized wireless technology, contemporaries initially viewed it as a means to enable telegraphy in inaccessible places that cables could not reach. Early radios acted as devices for naval ships to communicate with other boats and with land stations; users overlooked purposes beyond person-to-person communication. However, the potential for broadcasting—sending messages to a large group of potential listeners—did not develop until later in the medium’s history.

Broadcasting Arrives

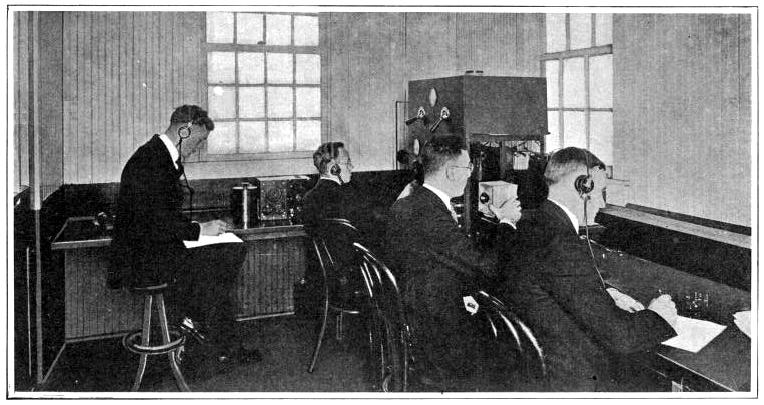

The relatively simple technology required to build a radio transmitter and receiver soon became accessible to the public. Amateur radio operators quickly crowded the airwaves, broadcasting messages to anyone within range. By 1912, they had incurred government regulatory measures that required licenses and limited broadcast ranges for radio operations (White). This regulation also gave the president the power to shut down all stations, a power notably exercised in 1917 upon the United States’ entry into World War I, to prevent amateur radio operators from interfering with the military’s use of radio waves for the duration of the war (White).

Wireless technology made radio as audiences know it today possible, but other technologies before the invention occasionally managed to replicate the modern, practical function as a mass communication medium. As early as the 1880s, people relied on telephones to transmit news, music, church sermons, and weather reports. In Budapest, Hungary, for example, a subscription service allowed individuals to listen to news reports and fictional stories on their telephones (White). Around this time, telephones also transmitted opera performances from Paris to London. In 1909, this innovation emerged in the United States as a pay-per-play phonograph service in Wilmington, Delaware (White). This service allowed subscribers to listen to specific music recordings on their telephones (White).

In 1906, Massachusetts resident Reginald Fessenden initiated the first radio transmission of the human voice; however, his efforts did not develop into a practical application (Grant, 1907). Ten years later, Lee de Forest utilized radio in a more modern sense when he established an experimental radio station, 2XG, in New York City. De Forest gave nightly broadcasts of music and news until World War I halted all transmissions for private citizens (White).

Radio’s Commercial Potential

After the World War I radio ban was lifted with the end of the conflict in 1919, several small stations began operating using technologies developed during the war. Many of these stations developed regular programming that included religious sermons, sports, and news (White). The dawn of commercial radio in the United States fundamentally reshaped the landscape of news dissemination. A pivotal moment occurred on November 2, 1920, when KDKA in Pittsburgh, recognized as the nation’s first commercial radio station, broadcast the returns of the Harding-Cox presidential election. This event was groundbreaking because KDKA delivered the results to listeners hours before the morning newspapers could be printed and distributed. The instant delivery of dramatic news presented an immediate challenge to the established press, leading to concerns from newspaper publishers who promptly threatened to cut off radio stations’ access to vital news sources, such as the Associated Press (AP) wire, fearing that radio would undermine their sales of “extra” editions.

Newspapers eventually adapted to this new competition, recognizing they could not compete with radio’s immediacy. They largely phased out special editions for breaking news, instead focusing on providing more in-depth analysis, commentary, and feature stories that radio’s early format couldn’t yet deliver. KDKA’s initial business model, standard for early radio stations, was not based on advertising revenue but instead on the idea of providing programming solely to encourage consumers to purchase more radio receivers manufactured by its parent company, Westinghouse. However, this model would quickly evolve.

As early as 1922, Schenectady, New York’s WGY broadcast over 40 original dramas, showing radio’s potential as a medium for drama. The WGY players created their scripts and performed them live on air. This same groundbreaking group also made the first known attempt at television drama in 1928 (McLeod, 1998). As radio began its rapid ascent in the 1920s, a fundamental question loomed over the new industry: how would this new mass medium sustain itself financially? This pressing concern was underscored in 1924 when Radio Broadcast magazine sponsored an essay contest titled, “Who Is to Pay for Broadcasting—and How?” The contest, offering a then-substantial prize of $500 (equivalent to approximately $9,000 in today’s money), highlighted the industry’s desperate search for a viable business model.

Among the early solutions considered were proposals for a “tithe” on all radio sales or the establishment of a substantial public endowment. The winning essay in the Radio Broadcast contest proposed a particular, yet ultimately impractical, solution: a $2 tax on each vacuum tube and a $0.50 tax on each crystal used in a receiver, with the collection and administration of these funds to be handled by a proposed Federal Bureau of Broadcasting. However, these suggestions, including the winning one, quickly proved utterly inadequate for the scale the industry was rapidly achieving. The rapidly escalating costs associated with producing high-quality content and, crucially, attracting popular entertainers, far outstripped the meager revenue potential of such component taxes or other public funding models.

In this economic vacuum, one solution emerged as the clear frontrunner. Despite initial resistance from some who feared it would compromise the medium’s integrity, advertising has swiftly become—and has remained—the primary source of revenue for radio in the United States. This embrace of commercial sponsorship, which effectively sidelined the initially preferred models, allowed radio stations to afford top talent and extensive programming, ultimately driving the medium’s explosive growth and cementing its role as a powerful advertising platform for decades to come. Businesses, such as department stores, which often had their radio stations, were among the first to utilize radio’s commercial applications. However, these stations did not advertise in a manner that would be recognizable to a modern radio listener. Early radio advertisements consisted only of a “genteel sales message broadcast during ‘business’ (daytime) hours, with no hard sell or mention of price (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).” Audiences initially considered radio advertising an unprecedented invasion of privacy, because—unlike newspapers, which people purchased at a newsstand—radios delivered content in the home and were present in the living room, where the whole family could hear (Sterling & Kittross, 2002). However, within a few years, advertising became readily accepted on radio programs. Advertising agencies even began producing their radio programs named after their products. Initially, ads ran only during the day, but as economic pressure intensified during the Great Depression in the 1930s, local stations sought new sources of revenue, and advertising became a standard part of the radio soundscape (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).

The Rise of Radio Networks

David Sarnoff, then an engineer for American Marconi, penned a pivotal document in 1915 known as the “Radio Music Box Memo.” This forward-thinking memo was revolutionary for its time, outlining a bold vision for radio as a mass communication tool, rather than merely a point-to-point telegraphic device. Sarnoff remarkably predicted a future where radio receivers, resembling simple “music boxes,” would bring news, music, lectures, and sporting events directly into people’s homes, making it an indispensable household utility.

However, Sarnoff’s prescient idea for commercial radio broadcasting was put on hold by the onset of World War I. During the conflict, the U.S. government, recognizing the strategic importance of radio, effectively nationalized the technology. The Navy purchased all existing transmitters and took control of radio operations, making it illegal for private citizens to own or operate a radio without explicit government permission. This wartime centralization of radio technology meant that Sarnoff’s broadcasting vision would not be fully realized until after the war’s conclusion, when the radio industry could shift its focus from military necessity to public entertainment.

Sarnoff’s vision, however, was far from halted by the war; it merely lay dormant, waiting for the opportune moment to blossom. The formation of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in 1919 was a strategic move driven by a crucial post-World War I concern: the desire to prevent foreign entities from dominating the burgeoning American radio industry, and to ensure that the U.S. government did not maintain permanent control over radio technology after its wartime nationalization. To achieve this, key American industrial and communication giants were brought together to pool their vast patent holdings. These included General Electric, which manufactured radio transmitters and had acquired American Marconi; AT&T, the global leader in wired communication with vital patents related to amplification; and Westinghouse, another electrical powerhouse holding numerous essential radio patents. Intriguingly, even the United Fruit Company played a role, contributing patents they had developed for their critical radio communications with ships transporting fruit from South American plantations.

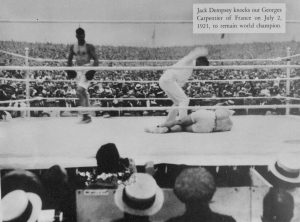

Sarnoff became RCA’s general manager and was finally in a position to champion his broadcasting concept. He demonstrated radio’s broad appeal by arranging the live broadcast of the Jack Dempsey-Georges Carpentier heavyweight boxing match in 1921, an event that captivated hundreds of thousands of listeners and ignited public demand for home radio receivers. This success provided the crucial momentum to push broadcasting into the mainstream. The primary objective of creating RCA was to consolidate thousands of disparate radio patents under a single American entity. This patent pool was vital, as it enabled various companies to cross-license technologies necessary for manufacturing and developing radio receivers and broadcasting equipment without the constant threat of litigation. This collaborative structure was designed to accelerate the development of radio from a niche point-to-point communication tool into a widely accessible mass medium. Ultimately, RCA’s foundational role in uniting these critical patents laid the groundwork for its subsequent dominance in the industry.

Meanwhile, in Europe. The British Broadcasting Company, founded in 1922, emerged with a distinct public service mission, aiming to inform, educate, and entertain the British public. In its earliest incarnation, the BBC’s operations were uniquely supported by revenue generated from the sale of radio receiving sets and compulsory radio-receiving licenses, establishing a funding model distinct from the advertising-driven approach taking root in the United States. This public service ethos would soon extend globally as the BBC began transmitting shortwave signals in multiple languages worldwide, particularly through what would become the BBC World Service.

This international reach proved critically crucial during World War II, when the BBC served as a vital voice against the Nazis. Its broadcasts delivered uncensored news and essential information to occupied territories and Allied forces, standing as an international voice of truth and resistance. Today, the BBC continues its formidable global presence, often claiming to reach a staggering 95% of the world’s population through a multi-platform strategy that leverages the Internet, alongside traditional FM, shortwave, and satellite communication. This extensive network is crucial to its mission of providing independent news, serving as a trusted source that is not censored by local governments, thereby upholding its long-standing commitment to impartial journalism on the global stage.

Under Sarnoff’s leadership in 1926, RCA established the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), America’s first major radio network. This marked a monumental shift, creating a standardized programming schedule and bringing entertainment, news, and cultural events to a mass audience nationwide. His influence extended beyond radio, as he became a leading proponent and investor in the development of television, famously pushing RCA’s research into electronic television systems that would eventually lead to the commercialization of the medium, first in black-and-white and later in color, further solidifying his legacy as a titan of electronic mass media. Groups of stations that carried syndicated network programs along with a variety of local shows soon formed their Red and Blue networks. Two years after the creation of NBC, the United Independent Broadcasters became the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) and began competing with the existing Red and Blue networks (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).

Although early network programming primarily focused on music, it soon evolved to include other innovative programs, such as variety shows. This format generally featured several different performers introduced by a host who provided the transition between acts. Variety shows included styles as diverse as jazz and early country music. At night, dramas and comedies such as Amos ’n’ Andy, The Lone Ranger, and Fibber McGee and Molly filled the airwaves. News, educational programs, and other types of talk programs also rose to prominence during the 1930s (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).

From Cigars to Customers: William Paley and the Birth of Modern Radio Advertising

The growth of radio networks in the 1920s gave rise to two distinct philosophies regarding their fundamental purpose. When the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) was founded by RCA in 1926, its initial approach, particularly under David Sarnoff, was largely centered on developing high-quality programming for the benefit of its listeners. The goal was to provide diverse content – from music and news to dramas and educational talks – thereby encouraging the public to purchase more radio sets, which was RCA’s primary business. The audience was seen as the end-user for whom the programming was created.

In contrast, William Paley approached radio from a purely commercial perspective when he took over what would become the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). Paley, who had started his career in his family’s cigar business, first recognized radio’s immense potential when he used it successfully to advertise their La Palina cigars. Seeing the undeniable power of compelling programming to influence consumer behavior, he purchased the struggling United Independent Broadcasters in 1928 and swiftly rebranded it as the Columbia Broadcasting System.

Paley’s genius lay in his reframing of the broadcasting business model. For him, the real clients were not the listeners, but the advertisers. He famously articulated the idea that the product of the radio network was the audience itself. CBS’s strategic focus was on attracting and delivering the largest possible audience to advertisers, who paid for access to this aggregated audience. This commercial-first philosophy would ultimately become the dominant model for American broadcasting, fundamentally shaping the industry’s trajectory and defining the relationship between content, audience, and revenue for decades to come.

The Radio Act of 1927

In the mid-1920s, profit-seeking companies, including department stores and newspapers, owned a majority of the nation’s broadcast radio stations, which promoted their owners’ businesses (ThinkQuest). Nonprofit groups such as churches and schools operated another third of the stations. As the number of radio stations outgrew the available frequencies, interference became a significant problem, prompting the government to intervene.

The Radio Act of 1927 established the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) to regulate the use of the airwaves. A year after its creation, the FRC reallocated station bandwidths to correct interference problems. The organization reserved 40 high-powered channels, setting aside 37 of these for network affiliates. The remaining 600 lower-powered bandwidths were allocated to stations that had to share the frequencies; this meant that as one station went off the air at a designated time, another station began broadcasting in its place. The Radio Act of 1927 enabled major networks, such as CBS and NBC, to gain a 70 percent share of U.S. broadcasting by the early 1930s, yielding them $72 million in profits by 1934 (McChesney, 1992). At the same time, nonprofit broadcasting fell to only 2 percent of the market (McChesney, 1992).

In protest of the favor shown by the 1927 Radio Act toward commercial broadcasting, struggling nonprofit radio broadcasters established the National Committee on Education by Radio to lobby for more outlets. Basing their argument on the notion that the airwaves—unlike newspapers—were a public resource, they asserted that groups working for the public good should take precedence over commercial interests. Nevertheless, the Communications Act of 1934 passed without addressing these issues, and radio continued as a mainly commercial enterprise (McChesney, 1992).

The Golden Age of Radio

The so-called Golden Age of Radio spanned from the 1930s to the mid-1950s. Because many associate the 1930s with the struggles of the Great Depression, it may seem contradictory that such a fruitful cultural occurrence arose during this decade. However, radio lent itself to the era. After the initial purchase of a receiver, radio provided free entertainment that replaced other, more costly pastimes, such as going to the movies.

Radio also presented an easily accessible form of media that existed on its schedule. Unlike reading newspapers or books, tuning in to a favorite program at a particular time became a part of listeners’ daily routine because it effectively forced them to plan their lives around the dial.

Daytime Radio Finds Its Market

During the Great Depression, radio became so successful that another network, the Mutual Broadcasting Network, began in 1934 to compete with NBC’s Red and Blue networks and the CBS network, creating a total of four national networks (Cashman, 1989). As the networks became more adept at generating profits, their broadcast selections began to take on a format that later evolved into modern television programming. Serial dramas and programs that focused on domestic work aired during the day to cater to female audiences. Advertisers targeted this demographic with commercials for domestic needs such as soap (Museum). Because soap companies often sponsored these programs, daytime serial dramas soon became known as soap operas. Some modern televised soap operas, such as Guiding Light, which ended in 2009, actually began in the 1930s as radio serials (Hilmes, 1999).

The Origins of Prime Time

During the evening, many families gathered to listen to the radio together. Popular evening comedy variety shows such as George Burns and Gracie Allen’s Burns and Allen, the Jack Benny Show, and the Bob Hope Show all began during the 1930s. These shows featured a central host—for whom the show was often named—and a series of sketch comedies, interviews, and musical performances, not unlike contemporary programs such as Saturday Night Live. Performed live before a studio audience, the programs thrived on a certain flair and spontaneity. Later in the evening, stations aired so-called prestige dramas such as Lux Radio Theater and Mercury Theatre on the Air. These shows featured prominent Hollywood actors recreating movies or acting out adaptations of literature (Hilmes).

Instant News

By the late 1930s, the popularity of radio news broadcasts had surpassed that of newspapers. Radio’s ability to emotionally draw its audiences close to events made for news that evoked stronger responses and, thus, greater interest than print news could. For example, the kidnapping and murder of the infant son of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh in 1932 prompted radio networks to set up mobile stations that covered events as they unfolded, broadcasting nonstop for several days and keeping listeners updated on every detail while tying them emotionally to the outcome (Brown, 1998).

As recording technology advanced, reporters gained the ability to record events in the field and bring them back to the studio to broadcast over the airwaves. In 1937, Herb Morrison witnessed the Hindenburg blimp explode into flames while attempting to land, killing 37 of its passengers. Stations later rebroadcast Morrison’s recording, including the sound of the exploding blimp, providing listeners with an unprecedented emotional connection to a national disaster. Morrison’s exclamation “Oh, the humanity!” became a common phrase of despair after the event (Brown, 1998).

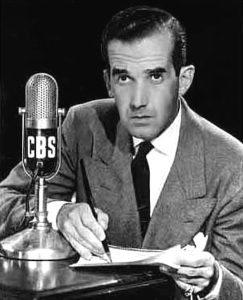

Radio news became even more critical during World War II, with programs such as Norman Corwin’s This Is War! seeking to bring more sober news stories to a radio dial dominated by entertainment. The program dealt with the realities of war somberly; at the beginning of the program, the host declared, “No one is invited to sit down and take it easy. Later, there’s a war on (Horten, 2002).” In 1940, Edward R. Murrow, a journalist working in England at the time, broadcast firsthand accounts of the German bombing of London, giving Americans a sense of the trauma and terror that the English were experiencing at the outset of the war (Horten, 2002). Radio news outlets broke the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor that propelled the United States into World War II in 1941. By 1945, radio news had become so efficient and pervasive that when Roosevelt died, only his wife, his children, and Vice President Harry S. Truman knew of it before the news spread over the public airwaves (Brown).

The Birth of the Federal Communications Commission

The Communications Act of 1934 established the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and marked the beginning of a new era of government regulation. The organization quickly began enacting influential radio decisions. In 1938, they decided to limit stations to 50,000 watts of broadcasting power, a ceiling that remains in effect today, although there have been some exceptions and adjustments over the years (Cashman). As a result of FCC antimonopoly rulings, the FCC forced RCA to sell its NBC Blue network; this spun-off division became the American Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) in 1943 (Brinson, 2004).

In 1949, the FCC established the Fairness Doctrine, stipulating that if broadcasters took a position on a particular issue, they had to provide equal time to all other reasonable positions on that issue (Browne & Browne, 1986). This tenet originated from the long-held notion that the airwaves functioned as a public resource and should therefore serve the public in some way. Although the regulation remained in effect until 1987, the impact of its core concepts remains a topic of debate. This chapter will explore the Fairness Doctrine and its impact in greater detail in a later section.

The Tragic History and Influence of FM Radio

In 1934, American electrical engineer Edwin Howard Armstrong achieved a monumental breakthrough in radio technology with his invention of Frequency Modulation (FM) radio. This innovation represented a significant improvement over the existing Amplitude Modulation (AM) radio, primarily because FM signals were far less susceptible to static and interference, resulting in a much clearer and higher-fidelity listening experience. Armstrong’s invention promised to revolutionize broadcasting by delivering a cleaner sound, free from the crackle and hiss familiar on AM.

However, Armstrong’s groundbreaking work was met not with widespread adoption but with fierce opposition from influential industry players. David Sarnoff, the head of RCA and Armstrong’s former mentor, viewed FM as a direct threat to RCA’s vast investments in AM radio and its burgeoning television ventures. Consequently, Armstrong found himself embroiled in decades of relentless legal battles, as RCA systematically attacked his patents and actively lobbied against the widespread commercial development of FM. This protracted and debilitating fight, combined with personal struggles including an estranged marriage and declining health, took a severe toll on Armstrong. Tragically, in 1954, after years of legal and financial exhaustion, he took his own life, dying without seeing his invention fully recognized or widely adopted to the extent it eventually would be.

As music came to dominate the airwaves, FM radio attracted new listeners due to its high-fidelity sound capabilities. When radio primarily featured dramas and other talk-oriented formats, sound quality had not mattered to many people, and the purchase of an FM receiver did not compete with the purchase of a new television in terms of entertainment value. As FM receivers decreased in price and stereo recording technology became more popular, the high-fidelity trend created a market for FM stations. Mostly affluent consumers began purchasing component stereos to achieve the highest sound quality possible from their recordings (Douglas, 2004). Although this audience often preferred classical and jazz stations to Top 40 radio, they were willing to tolerate new music and ideas (Douglas, 2004).

Both the high-fidelity market and the growing youth counterculture of the 1960s had similar goals for the FM spectrum. Both groups eschewed AM radio due to its predictable programming, poor sound quality, and over-commercialization. Both groups sought to treat music as a meaningful experience, rather than merely a trendy pastime or a means to earn a living. Many adherents to the youth counterculture of the 1960s came from affluent, middle-class families, and their tastes came to define a new era of consumer culture. The goals and market potential of both the high-fidelity lovers and the youth counterculture created an atmosphere on the FM dial that audiences had never experienced (Douglas, 2004).

Between 1960 and 1966, the number of households capable of receiving FM transmissions increased from approximately 6.5 million to over 40 million. The FCC also aided FM by issuing its nonduplication ruling in 1964. Before this regulation, many AM stations had other stations on the FM spectrum that duplicated the AM programming. The nonduplication rule compelled FM stations to create their original programming, thereby opening up the spectrum for established networks to develop new stations (Douglas, 2004).

The late 1960s saw new disc jockeys taking greater liberties with established practices; these liberties included playing several songs in a row before going to a commercial break or airing album tracks that exceeded 10 minutes in length. University stations and other nonprofit ventures to which the FCC had assigned frequencies during the late 1940s popularized this format, and, over time, commercial stations attempted to replicate their success by playing fewer commercials and allowing their disc jockeys to have a say in their playlists. Although this made for popular listening formats, FM stations struggled to make the kinds of profits that the AM spectrum drew (Douglas, 2004).

In 1974, FM radio accounted for one-third of all radio listening but only 14 percent of radio profits (Douglas, 2004). Large network stations and advertisers began to market heavily to the FM audience in an attempt to correct this imbalance. Stations began tightening their playlists and narrowing their formats to please advertisers and generate greater revenues. By the end of the 1970s, radio stations began to play specific formats, and the progressive radio of the previous decade had become difficult to find (Douglas, 2004).

Radio on the Margins

Despite the networks’ hold on programming, educational stations continued to operate at universities and in some municipalities. They broadcast programs such as School of the Air and College of the Air, as well as roundtable and town hall forums. In 1940, the FCC reserved a set of frequencies in the lower range of the FM radio spectrum for public education purposes as part of its regulation of the new spectrum. The reservation of FM frequencies gave educational stations a boost. Still, FM proved initially unpopular due to a setback in 1945, when the FCC relocated the FM bandwidth to a higher set of frequencies, ostensibly to avoid interference problems (Longley, 1968). This change required the purchase of new equipment by both consumers and radio stations, thus significantly slowing the widespread adoption of FM radio.

The blossoming sounds of rock ‘n’ roll in the mid-20th century were powerfully amplified by pioneering radio disc jockeys who dared to defy the norms of racial segregation. Among the most influential was Dewey Phillips, whose “Red, Hot & Blue” radio show on WHBQ in Memphis, Tennessee, became a cultural melting pot. In a deeply segregated South, Phillips fearlessly curated a playlist that transcended racial divides, attracting an unprecedented multi-racial audience, including both Black and white teenagers, who eagerly tuned in.

Phillips’s groundbreaking approach lay in his willingness to regularly spin R&B records, a genre then largely confined to Black radio stations and considered “race music.” By enthusiastically playing these rhythm and blues tracks, Phillips exposed a vital segment of white youth to the energetic, blues-infused sounds that would become the foundation of rock ‘n’ roll. His show was not just a source of music; it was a cultural bridge that inadvertently helped dismantle social barriers, directly contributing to the cross-cultural appeal and eventual mainstream success of rock ‘n’ roll.

The Pacifica Radio network represents an enduring anomaly in the field of educational stations. Begun in 1949 to counteract the effects of commercial radio by bringing educational programs and dialogue to the airwaves, Pacifica has grown from a single station—Berkeley, California’s KPFA—to a network of five stations and more than 200 affiliates (Pacifica Network). From the outset, Pacifica aired newer classical, jazz, and folk music along with lectures, discussions, and interviews with public artists and intellectuals. Pacifica refuses to accept money from commercial advertisers, instead relying on donations from listeners and grants from institutions such as the Ford Foundation, and describes itself as listener-supported (Mitchell, 2005).

The growth of border stations signifies another vital innovation on the fringes of the radio dial. Located just across the Mexican border, these stations were exempt from following FCC or U.S. regulatory laws. Because the stations broadcast at 250,000 watts and higher, their listening range covered much of North America. Their content also diverged—at the time markedly—from that of U.S. stations. For example, Dr. John Brinkley started station XERF in Del Rio, Mexico, after the closure of his station in Nebraska, and he used the border station in part to promote a dubious goat gland operation that supposedly cured sexual impotence (Dash, 2008). Besides the goat gland promotion, the station and others like it often carried music, like country and western, that regular network radio did not broadcast. Later border station disc jockeys, such as Wolfman Jack, played a crucial role in introducing rock and roll music to a wider audience (Rudel, 2008).

Television Steals the Show

Radio enjoyed considerable success as a medium during the 1920s and 1930s because no other medium could replicate its reach. This shift occurred in the late 1940s and early 1950s as television gained popularity. A 1949 poll of people who had seen television found that almost half of them believed that radio would fail (Gallup, 1949). Television sets had come on the market by the late 1940s, and by 1951, more Americans watched television during prime time than ever (Bradley). Famous radio programs such as The Bob Hope Show transitioned into television shows, further diminishing radio’s unique offerings (Cox, 1949).

Surprisingly, some of radio’s most critically lauded dramas launched during this period. Gunsmoke, an adult-oriented Western show (that later became television’s longest-running show) began in 1952; crime drama Dragnet, later made famous in both television and film, broadcast between 1949 and 1957; and Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar aired from 1949 to 1962, when CBS canceled its remaining radio dramas. However, these respected radio dramas represent the last of their kind (Cox, 2002). Although television did not kill radio, it marked the end of its Golden Age.

Transition to Top 40

As radio networks abandoned the dramas and variety shows that had previously sustained their formats, radio stations decided to focus on what they could still do better than any other mass media: play music. With advertising dollars down and the emergence of better recording formats, it made good business sense for radio to focus on shows that played prerecorded music. As strictly music stations began to rise, innovations to increase their profitability appeared. The Top 40 station emerged, a concept that supposedly originated from observing jukebox patrons repeatedly playing the same songs (Brewster & Broughton, 2000). Robert Storz and Gordon McLendon successfully adapted existing radio stations to fit this new format. In 1956, the creation of limited playlists further refined the format by providing about 50 songs that disc jockeys played repeatedly every day. By the early 1960s, many stations had developed limited playlists of only 30 songs (Walker, 2001).

Another musically fruitful innovation came with the increase of Black disc jockeys and programs created for Black audiences. Because its advertisers had nowhere to go in a media market dominated by White performers, Black radio became more common on the AM dial. As traditional programming left the radio, disc jockeys emerged as the medium’s new personalities, engaging in more conversation between songs and building followings. Early Black disc jockeys even began improvising rhymes over the music, pioneering techniques that later became rap and hip-hop. This new personality-driven style helped bring early rock and roll to new audiences (Walker, 2001).

The Rise of Public Radio

After the Golden Age of Radio came to an end, most listeners tuned in to radio stations to hear music. The variety shows and talk-based programs that had sustained radio in the early years could no longer draw enough listeners to make them a successful business proposition. One divergent path from this general trend, however, grew from the success of public radio.

Groups such as the Ford Foundation had funded public media sources during the early 1960s. When the foundation decided to withdraw its funding in the middle of the decade, the federal government stepped in with the passage of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. This act established the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) and tasked it with generating funding for public television and radio stations. The CPB, in turn, created National Public Radio (NPR) in 1970 to provide programming for already-operating stations. Until 1982, the CPB entirely and exclusively funded NPR. Public radio’s first program, All Things Considered, delivered news that focused on analysis and interpretive reporting rather than cutting-edge coverage. In the mid-1970s, NPR attracted Washington-based journalists such as Cokie Roberts and Linda Wertheimer to its ranks, giving the coverage a more professional, hard-reporting edge (Schardt, 1996).

However, in 1983, public radio stood on the brink of financial collapse. NPR survived in part by relying more on its member stations to hold fundraising drives, now a vital component of public radio’s business model. A major donation from the Kroc Foundation in 2003 provided a significant boost to NPR’s finances.

Since its early days, NPR has evolved into a respected news provider. Its coverage of major events, such as the Gulf War and the 2001 terrorist attacks, has gained it a wider audience. While NPR has faced criticism for a perceived liberal bias, it has also attracted a significant conservative audience. As of 2024, NPR boasts more than 1,000 member stations and has 28.7 million weekly on-air listeners and 42 million weekly audience members across all platforms. Its digital presence, including podcasts, Tiny Desk concerts, online news, and social media, has further expanded its reach and influence. NPR’s future appears uncertain based on President Donald Trump’s request to cut funding for NPR.

Public radio distributors and stations have expanded their programming beyond news and current events to include a wide range of cultural and entertainment offerings. Quiz shows like Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me! and cooking shows like Radio Kitchen have become popular favorites. Storytelling programs like This American Life and Radiolab have pioneered new genres of free-form radio documentary. Meanwhile, shows like The Moth have revived older radio formats. This diversity of programming has helped public radio attract a wider audience and showcase its potential as a platform for storytelling, education, and entertainment.

Conglomerates

For decades, the American radio landscape was characterized by strict ownership limitations imposed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), designed to ensure diversity of voices and prevent undue market concentration. Before 1985, these regulations stipulated that no single person or company could own more than seven AM, seven FM, and seven television stations nationwide. These caps fostered a more fragmented and localized industry, with numerous independent owners operating stations across the country.

However, this regulatory framework underwent a dramatic transformation with the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. This landmark legislation ushered in an era of significant deregulation of broadcast ownership. Critically, the Act eliminated the national cap on the total number of radio stations a single company could own, opening the door for unprecedented consolidation.

Following the 1996 Act, a single company could now own an unlimited number of radio stations across the United States. Local market limits were also substantially relaxed, allowing companies to acquire multiple stations within the same market, in some cases up to eight stations (depending on the overall size of the market). This shift led to a massive wave of mergers and acquisitions, fundamentally reshaping the radio industry from one dominated by local ownership to one increasingly controlled by a handful of large, national broadcast conglomerates.

As large corporations, such as Clear Channel Communications (now iHeartMedia), acquired stations around the country, they reformatted stations that had once competed against one another, so that each focused on a distinct format. This practice led to mainstream radio’s present state, in which narrow formats target particular demographic audiences.

Ultimately, although the industry consolidation of the 1990s made radio profitable, it reduced local coverage and diversity of programming. Because stations around the country served as outlets for a single network, the radio landscape became more uniform and predictable (Keith, 2010). Much as with chain restaurants and stores, some people enjoy this type of predictability, while others prefer a more localized, unique experience (Keith, 2010).