Source Edition – Chapters 4-6

Chapter 4: Newspapers

4.1 Newspapers

4.2 History of Newspapers

4.3 Different Styles and Models of Journalism

4.4 How Newspapers Control the Public’s Access to Information and Impact American Pop Culture

4.5 Current Popular Trends in the Newspaper Industry

4.6 Online Journalism Redefines News

4.1 Newspapers

Newspaper Wars

Figure 4.1

The two major newspapers, the The Wall Street Journal and the The New York Times, battle for their place in the print world.

dennis crowley – Wall Street Journal – CC BY 2.0; Aaron Edwards – no-more-war – CC BY-NC 2.0.

On April 26, 2010, Wired magazine proclaimed that a “clash of the titans” between two major newspapers, The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, was about to take place in the midst of an unprecedented downward spiral for the print medium (Burskirk, 2010). Rupert Murdoch, owner of The Wall Street Journal, had announced that his paper was launching a new section, one covering local stories north of Wall Street, something that had been part of The New York Times’ focus since it first began over a century before. New York Times Chairman Arthur Sultzberger Jr. and CEO Janet Robinson pertly responded to the move, welcoming the new section and acknowledging the difficulties a startup can face when competing with the well-established New York Times (Burskirk, 2010).

Despite The New York Times’ droll response, Murdoch’s decision to cover local news indeed presented a threat to the newspaper, particularly as the two publications continue their respective moves from the print to the online market. In fact, some believe that The Wall Street Journal’s decision to launch the new section has very little to do with local coverage and everything to do with the Internet. Newspapers are in a perilous position: Traditional readership is declining even as papers are struggling to create a profitable online business model. Both The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times are striving to remain relevant as competition is increasing and the print medium is becoming unprofitable.

In light of the challenges facing the newspaper industry, The Wall Street Journal’s new section may have a potentially catastrophic effect on The New York Times. Wired magazine described the decision, calling it “two-pronged” to “starve the enemy and capture territory (Burskirk, 2010).” By offering advertising space at a discount in the new Metro section, The Journal would make money while partially cutting The Times off from some of its primary support. Wired magazine also noted that the additional material would be available to subscribers through the Internet, on smartphones, and on the iPad (Burskirk, 2010).

Attracting advertising revenue from The New York Times may give The Wall Street Journal the financial edge it needs to lead in the online news industry. As newspapers move away from print publications to online publications, a strong online presence may secure more readers and, in turn, more advertisers—and thus more revenue—in a challenging economic climate.

This emerging front in the ongoing battle between two of the country’s largest newspapers reveals a problem the newspaper industry has been facing for some time. New York has long been a battleground for other newspapers, but before Murdoch’s decision, these two papers coexisted peacefully for over 100 years, serving divergent readers by focusing on different stories. However, since the invention of radio, newspapers have worried about their future. Even though readership has been declining since the 1950s, the explosion of the Internet and the resulting accessibility of online news has led to an unprecedented drop in subscriptions since the beginning of the 21st century. Also hit hard by the struggling economy’s reluctant advertisers, most newspapers have had to cut costs. Some have reinvented their style to appeal to new audiences. Some, however, have simply closed. As this struggle for profit continues, it’s no surprise that The Wall Street Journal is trying to outperform The New York Times. But how did newspapers get to this point? This chapter provides historical context of the newspaper medium and offers an in-depth examination of journalistic styles and trends to illuminate the mounting challenges for today’s industry.

References

Burskirk, Eliot Van “Print War Between NYT and WSJ Is Really About Digital,” Wired, April 26, 2010, http://www.wired.com/epicenter/2010/04/print-war-between-nyt-and-wsj-is-really-about-digital.

4.4 How Newspapers Control the Public’s Access to Information and Impact American Pop Culture

Learning Objectives

- Describe two ways that newspapers control stories.

- Define watchdog journalism.

- Describe how television has impacted journalistic styles.

Since 1896, The New York Times has printed the phrase “All the News That’s Fit to Print” as its masthead motto. The phrase itself seems innocent enough, and it has been published for such a long time now that many probably skim over it without giving it a second thought. Yet, the phrase represents an interesting phenomenon in the newspaper industry: control. Papers have long been criticized for the way stories are presented, yet newspapers continue to print—and readers continue to buy them.

“All the News That’s Fit to Print”

In 1997, The New York Times publicly claimed that it was “an independent newspaper, entirely fearless, free of ulterior influence and unselfishly devoted to the public welfare (Herman, 1998).” Despite this public proclamation of objectivity, the paper’s publishers have been criticized for choosing which articles to print based on personal financial gain. In reaction to that statement, scholar Edward S. Herman wrote that the issue is that The New York Times “defin[es] public welfare in a manner acceptable to their elite audience and advertisers (Herman, 1998).” The New York Times has continually been accused of determining what stories are told. For example, during the 1993 debate over the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), The New York Times clearly supported the agreement. In doing so, the newspaper exercised editorial control over its publication and the information that went out to readers.

However, The New York Times is not the only newspaper to face accusations of controlling which stories are told. In his review of Read All About It: The Corporate Takeover of America’s Newspapers, Steve Hoenisch, editor of Criticism.com, offers these harsh words about what drives the stories printed in today’s newspapers:

I’ve always thought of daily newspapers as the guardians of our—meaning the public’s—right to know. The guardians of truth, justice, and public welfare and all that. But who am I fooling? America’s daily newspapers don’t belong to us. Nor, for that matter, do they even seek to serve us any longer. They have more important concerns now: appeasing advertisers and enriching stockholders (Hoenisch).

More and more, as readership declines, newspapers must answer to advertisers and shareholders as they choose which stories to report on.

However, editorial control does not end there. Journalists determine not only what stories are told but also how those stories are presented. This issue is perhaps even more delicate than that of selection. Most newspaper readers still expect news to be reported objectively and demand that journalists present their stories in this manner. However, careful public scrutiny can burden journalists, while accusations of controlling information affect their affiliated newspapers. However, this scrutiny takes on importance as the public turns to journalists and newspapers to learn about the world.

Journalists are also expected to hold themselves to high standards of truth and originality. Fabrication and plagiarism are prohibited. If a journalist is caught using these tactics, then his or her career is likely to end for betraying the public’s trust and for damaging the publication’s reputation. For example, The New York Times reporter Jayson Blair lost his job in 2003 when his plagiary and fabrication were discovered, and The New Republic journalist Stephen Glass was fired in 1998 for inventing stories, quotes, and sources.

Despite the critiques of the newspaper industry and its control over information, the majority of newspapers and journalists take their roles seriously. Editors work with journalists to verify sources and to double-check facts so readers are provided accurate information. In this way, the control that journalists and newspapers exert serves to benefit their readers, who can then be assured that articles printed are correct.

The New York Times Revisits Old Stories

Despite the criticism of The New York Times, the famous newspaper has been known to revisit their old stories to provide a new, more balanced view. One such example occurred in 2004 when, in response to criticism on their handling of the Iraq War, The New York Times offered a statement of apology. The apology read:

We have found a number of instances of coverage that was not as rigorous as it should have been. In some cases, information that was controversial then, and seems questionable now, was insufficiently qualified or allowed to stand unchallenged. Looking back, we wish we had been more aggressive in re-examining the claims as new evidence emerged—or failed to emerge (New York Times, 2004).

Although the apology was risky—it essentially admitted guilt in controlling a controversial story—The New York Times demonstrated a commitment to ethical journalism.

Watchdog Journalism

One way that journalists control stories for the benefit of the public is by engaging in watchdog journalism. This form of journalism provides the public with information about government officials or business owners while holding those officials to high standards of operation. Watchdog journalism is defined as:

(1) independent scrutiny by the press of the activities of government, business and other public institutions, with an aim toward (2) documenting, questioning, and investigating those activities, to (3) provide publics and officials with timely information on issues of public concern (Bennett & Serrin, 2005).

One of the most famous examples of watchdog journalism is the role that Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post played in uncovering information about the Watergate break-in and scandal that ultimately resulted in President Richard Nixon’s resignation. Newspapers and journalists often laud watchdog journalism, one of the most important functions of newspapers, yet it is difficult to practice because it requires rigorous investigation, which in turn demands more time. Many journalists often try to keep up with news as it breaks, so journalists are not afforded the time to research the information—nor to hone the skills—required to write a watchdog story. “Surviving in the newsroom—doing watchdog stories—takes a great deal of personal and political skill. Reporters must have a sense of guerilla warfare tactics to do well in the newsroom (Bennett & Serrin, 2005).”

To be successful, watchdog journalists must investigate stories, ask tough questions, and face the possibility of unpopularity to alert the public to corruption or mismanagement while elevating the public’s expectations of the government. At the same time, readers can support newspapers that employ this style of journalism to encourage the press to engage in the challenging watchdog form of journalism. As scholars have observed, “Not surprisingly, watchdog journalism functions best when reporters understand it and news organizations and their audiences support it (Bennett & Serrin, 2005).”

Impact of Television and the Internet on Print

Newspapers have control over which stories are told and how those stories are presented. Just as the newspaper industry has changed dramatically over the years, journalistic writing styles have been transformed. Many times, such changes mirrored a trend shift in readership; since the 1950s, however, newspapers have had to compete with television journalism and, more recently, the Internet. Both television and the Internet have profoundly affected newspaper audiences and journalistic styles.

Case Study: USA Today

USA Today, founded in 1982 and known for its easy-to-read stories, is but one example of a paper that has altered its style to remain competitive with television and the Internet. In the past, newspapers placed their primary focus on the written word. Although some newspapers still maintain the use of written narration, many papers have shifted their techniques to attract a more television-savvy audience. In the case of USA Today, the emphasis lies on the second track—the visual story—dominated by large images accompanied by short written stories. This emphasis mimics the television presentation format, allowing the paper to cater to readers with short attention spans.

A perhaps unexpected shift in journalistic writing styles that derives from television is the more frequent use of present tense, rather than past tense, in articles. This shift likely comes from television journalism’s tendency to allow a story to develop as it is being told. This subtle but noticeable shift from past to present tense in narration sometimes brings a more dramatic element to news articles, which may attract readers who otherwise turn to television news programs for information.

Like many papers, USA Today has redesigned its image and style to keep up with the sharp immediacy of the Internet and with the entertainment value of television. In fact, the paper’s management was so serious about their desire to compete with television that from 1988 to 1990 they mounted a syndicated television series titled USA Today: The Television Show (later retitled USA Today on TV) (Internet Movie Database). Despite its short run, the show demonstrated the paper’s focus on reaching out to a visual audience, a core value that it has maintained to this day. Today, USA Today has established itself as a credible and reliable news source, despite its unorthodox approach to journalism.

Key Takeaways

- Newspapers control which stories are told by selecting which articles make it to print. They also control how stories are told by determining the way in which information is presented to their readers.

- Watchdog journalism is an investigative approach to reporting that aims to inform citizens of occurrences in government and businesses.

- Television has not only contributed to the decline of readership for newspapers but has also impacted visual and journalistic styles. Newspapers, such as USA Today, have been profoundly affected by the television industry. USA Today caters to television watchers by incorporating large images and short stories, while primarily employing the present tense to make it seem as though the story is unfolding before the reader.

Exercises

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Compare the journalistic styles of USA Today and The Wall Street Journal. Examine differences in the visual nature of the newspapers as well as in the journalistic style.

- How has television affected these particular newspapers?

- What noticeable differences do you observe? Can you find any similarities?

- How did each newspaper cover events differently? How did each newspaper’s coverage change the focus and information told? Did you find any watchdog stories, and, if so, what were they?

References

Bennett, W. Lance and William Serrin, “The Watchdog Role,” in The Institutions of American Democracy: The Press, ed. Geneva Overholser and Kathleen Hall Jamieson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 169.

Herman, Edward S. “All the News Fit to Print: Structure and Background of the New York Times,” Z Magazine, April 1998, http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/Herman%20/AllNewsFit_Herman.html.

Hoenisch, Steven. “Corporate Journalism,” review of Read All About It: The Corporate Takeover of America’s Newspapers, by James D. Squires, http://www.criticism.com/md/crit1.html#section-Read-All-About-It.

Internet Movie Database, “U.S.A Today: The Television Series,” Internet Movie Database, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0094572/.

New York Times, Editorial, “The Times and Iraq,” New York Times, May 26, 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/26/international/middleeast/26FTE_NOTE.html.

4.6 Online Journalism Redefines News

Learning Objectives

- Describe two ways in which online reporting may outperform traditional print reporting.

- Explain the greatest challenges newspapers face as they transition to online journalism.

The proliferation of online communication has had a profound effect on the newspaper industry. As individuals turn to the Internet to receive news for free, traditional newspapers struggle to remain competitive and hold onto their traditional readers. However, the Internet’s appeal goes beyond free content. This section delves further into the Internet and its influence on the print industry. The Internet and its role in media are explored in greater detail in Chapter 11 “The Internet and Social Media” of this textbook.

Competition From Blogs

Weblogs, or blogs, have offered a new take on the traditional world of journalism. Blogs feature news and commentary entries from one or more authors. However, journalists differ on whether the act of writing a blog, commonly known as blogging, is, in fact, a form of journalism.

Indeed, many old-school reporters do not believe blogging ranks as formal journalism. Unlike journalists, bloggers are not required to support their work with credible sources. This means that stories published on blogs are often neither verified nor verifiable. As Jay Rosen, New York University journalism professor, writes, “Bloggers are speakers and writers of their own invention, at large in the public square. They’re participating in the great game of influence called public opinion (Rosen, 2004).” Despite the blurry lines of what constitutes “true” journalism—and despite the fact that bloggers are not held to the same standards as journalists—many people still seek out blogs to learn about news. Thus, blogs have affected the news journalism industry. According to longtime print journalist and blogger Gina Chen, “Blogging has changed journalism, but it is not journalism (Chen, 2009).”

Advantages Over Print Media

Beyond the lack of accountability in blogging, blogs are free from the constraints of journalism in other ways that make them increasingly competitive with traditional print publications. Significantly, Internet publication allows writers to break news as soon as it occurs. Unlike a paper that publishes only once a day, the Internet is constantly accessible, and information is ready at the click of a mouse.

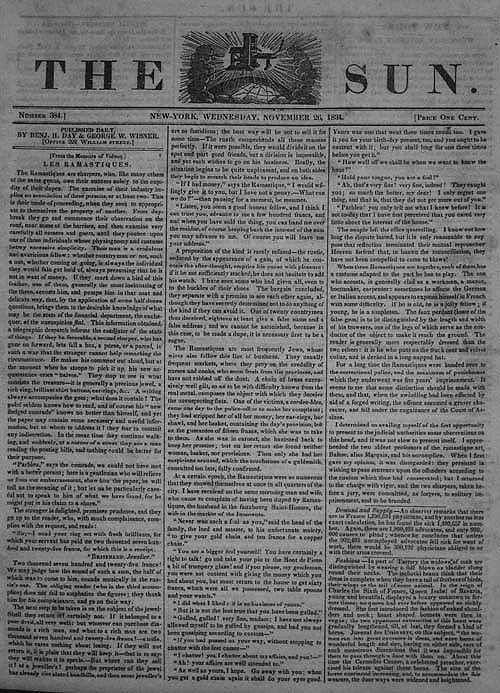

In 1998, the Internet flexed its rising journalistic muscle by breaking a story before any major print publication: the Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinsky scandal. The Drudge Report, an online news website that primarily consists of links to stories, first made the story public, claiming to have learned of the scandal only after Newsweek magazine failed to publish it. On January 18, 1998, the story broke online with the title “Newsweek Kills Story on White House Intern. Blockbuster Report: 23-year-old, Former White House Intern, Sex Relationship with President.” The report gave some details on the scandal, concluding the article with the phrase “The White House was busy checking the Drudge Report for details (Australian Politics, 1998).” This act revealed the power of the Internet because of its superiority in timeliness, threatening the relevancy of slower newspapers and news magazines.

Print media also continuously struggle with space constraints, another limit that the Internet is spared. As newspapers contemplate making the transition from print to online editions, several editors see the positive effect of this particular issue. N. Ram, editor in chief of The Hindu, claims, “One clear benefit online editions can provide is the scope this gives for accommodating more and longer articles…. There need be no space constraints, as in the print edition (Viswanathan, 2010).” With the endless writing space of the Internet, online writers have the freedom to explore topics more fully, to provide more detail, and to print interviews or other texts in their entirety—opportunities that many print journalists have longed for since newspapers first began publishing.

Online writing also provides a forum for amateurs to enter the professional realm of writing. With cost-cutting forcing newspapers to lay off writers, more and more would-be journalists are turning to the Internet to find ways to enter the field. Interestingly, the blogosphere has launched the careers of journalists who otherwise may never have pursued a career in journalism. For example, blogger Molly Wizenberg founded the blog Orangette because she didn’t know what to do with herself: “The only thing I knew was that, whatever I did, it had to involve food and writing (Wyke, 2009).” After Orangette became a successful food blog, Wizenberg transitioned into writing for a traditional media outlet: food magazine Bon Appetit.

Online Newspapers

With declining readership and increasing competition from blogs, most newspapers have embraced the culture shift and have moved to online journalism. For many papers, this has meant creating an online version of their printed paper that readers will have access to from any location, at all times of the day. By 2010, over 10,000 newspapers had gone online. But some smaller papers—particularly those in two-paper communities—have not only started websites, but have also ceased publication of their printed papers entirely.

One such example is Seattle’s Post-Intelligencer. In 2009, the newspaper stopped printing, “leaving the rival Seattle Times as the only big daily in town (Folkenflik, 2009).” As Steve Swartz, president of Hearst Newspapers and owner of the Post-Intelligencer, commented about the move to online-only printing, “Being the second newspaper in Seattle didn’t work. We are very enthusiastic, however, about this experiment to create a digital-only business in Seattle with a robust community website at its core (Folkenflik, 2009).” For the Post-Intelligencer, the move meant a dramatic decrease in its number of staff journalists. The printed version of the paper employed 135 journalists, but the online version, Seattlepi.com, employs only two dozen. For Seattlepi.com, this shift has been doubly unusual because the online-only newspaper is not really like a traditional newspaper at all. As Swartz articulated, “Very few people come to our website and try to re-create the experience of reading a newspaper—in other words, spending a half-hour to 45 minutes and really reading most of the articles. We don’t find people do that on the Web (Folkenflik, 2009).” The online newspaper is, in reality, still trying to figure out what it is. Indeed, this is an uncomfortable position familiar to many online-only papers: trapped between the printed news world and the online world of blogs and unofficial websites.

During this transitional time for newspapers, many professional journalists are taking the opportunity to enter the blogosphere, the realm of bloggers on the Internet. Journalist bloggers, also known as beatbloggers, have begun to utilize blogs as “tool[s] to engage their readers, interact with them, use them as sources, crowdsource their ideas and invite them to contribute to the reporting process,” says beatblogger Alana Taylor (Taylor, 2009). As beatblogging grows, online newspapers are harnessing the popularity of this new phenomenon and taking advantage of the resources provided by the vast Internet audience through crowdsourcing (outsourcing problem solving to a large group of people, usually volunteers). Blogs are becoming an increasingly prominent feature on news websites, and nearly every major newspaper website displays a link to the paper’s official blogs on its homepage. This subtle addition to the web pages reflects the print industry’s desire to remain relevant in an increasingly online world.

Even as print newspapers are making the transformation to the digital world with greater or less success, Internet news sites that were never print papers have begun to make waves. Sites such as The Huffington Post, The Daily Beast, and the Drudge Report are growing in popularity. For example, The Huffington Post displays the phrase “The Internet Newspaper: News, Blogs, Video, Community” as its masthead, reiterating its role and focus in today’s media-savvy world (Huffington Post). In 2008, former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown cofounded and began serving as editor in chief of The Daily Beast. On The Daily Beast’s website, Brown has noted its success: “I revel in the immediacy, the responsiveness, the real-time-ness. I used to be the impatient type. Now I’m the serene type. Because how can you be impatient when everything happens right now, instantly (Brown, 2009)?”

Some newspapers are also making even more dramatic transformations to keep up with the changing online world. In 2006, large newspaper conglomerate GateHouse Media began publishing under a Creative Commons license, giving noncommercial users access to content according to the license’s specifications. The company made the change to draw in additional online viewers and, eventually, revenue for the newspapers. Writer at the Center for Citizen Media, Lisa Williams, explains in her article published by PressThink.org:

GateHouse’s decision to CC license its content may be a response to the cut-and-paste world of weblogs, which frequently quote and point to newspaper stories. Making it easier—and legal—for bloggers to quote stories at length means that bloggers are pointing their audience at that newspaper. Getting a boost in traffic from weblogs may have an impact on online advertising revenue, and links from weblogs also have an impact on how high a site’s pages appear in search results from search engines such as Google. Higher traffic, and higher search engine rankings build a site’s ability to make money on online ads (Williams, 2006).

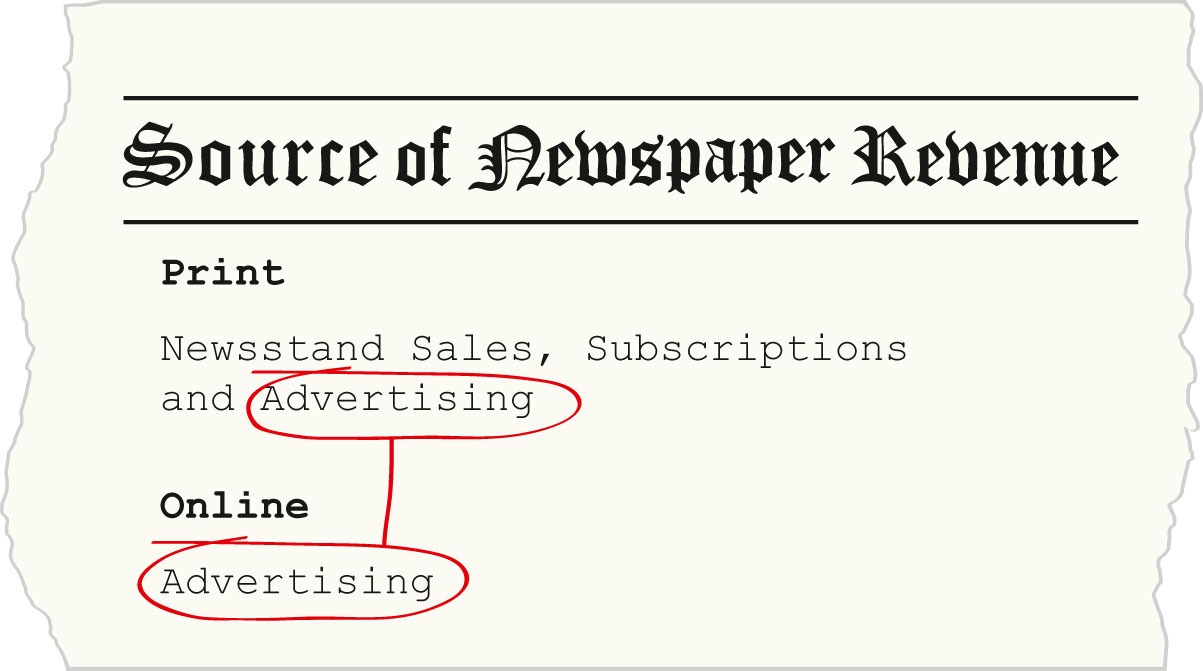

GateHouse Media’s decision to alter its newspapers’ licensing agreement to boost advertising online reflects the biggest challenge facing the modern online newspaper industry: profit. Despite shrinking print-newspaper readership and rising online readership, print revenue remains much greater than digital revenue because the online industry is still determining how to make online newspapers profitable. As one article notes:

The positive news is that good newspapers like The New York Times, The Guardian, The Financial Times, and The Wall Street Journal now provide better, richer, and more diverse content in their Internet editions…. The bad news is that the print media are yet to find a viable, let alone profitable, revenue model for their Internet journalism (Viswanathan, 2010).

The issue is not only that information on the Internet is free but also that advertising is far less expensive online. As National Public Radio (NPR) reports, “The online-only plan for newspapers remains an unproven financial model; there are great savings by scrapping printing and delivery costs, but even greater lost revenues, since advertisers pay far more money for print ads than online ads (Folkenflik).”

Despite these challenges, newspapers both in print and online continue to seek new ways to provide the public with accurate, timely information. Newspapers have long been adapting to cultural paradigm shifts, and in the face of losing print newspapers altogether, the newspaper industry continues to reinvent itself to keep up with the digital world.

Key Takeaways

- Print newspapers face increasing challenges from online media, particularly amateur blogs and professional online news operations.

- Internet reporting outperforms traditional print journalism both with its ability to break news as it happens and through its lack of space limitations. Still, nonprofessional Internet news is not subject to checks for credibility, so some readers and journalists remain skeptical.

- As newspapers move to online journalism, they must determine how to make that model profitable. Most online newspapers do not require subscriptions, and advertising is significantly less expensive online than it is in print.

Exercises

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Choose a topic on which to conduct research. Locate a blog, a print newspaper, and an online-only newspaper that have information about the topic.

- What differences do you notice in style and in formatting?

- Does one appeal to you over the others? Explain.

- What advantages does each source have over the others? What disadvantages?

- Consider the changes the print newspaper would need to make to become an online-only paper. What challenges would the print newspaper face in transitioning to an online medium?

End-of-Chapter Assessment

Review Questions

-

Section 1

- Which European technological advancement of the 1400s forever changed the print industry?

- Which country’s “weeklies” provided a stylistic format that many other papers followed?

- In what ways did the penny paper transform the newspaper industry?

- What is sensationalism and how did it become a prominent style in the journalism industry?

-

Section 2

- What are some challenges of objective journalism?

- What are the unique features of the inverted pyramid style of journalistic writing?

- How does literary journalism differ from traditional journalism?

- What are the differences between consensus journalism and conflict journalism?

-

Section 3

- In what two ways do newspapers control information?

- What are some of the defining features of watchdog journalism?

- Using USA Today as a model, in what tangible ways has television affected the newspaper industry and styles of journalism?

-

Section 4

- What are a few of the country’s most prominent newspapers, and what distinguishes them from one another?

- Name and briefly describe three technological advances that have affected newspaper readership.

-

Section 5

- In what ways might online reporting benefit readers’ access to information?

- Why are print newspapers struggling as they transition to the online market?

Critical Thinking Questions

- Have sensationalism or yellow journalism retained any role in modern journalism? How might these styles impact current trends in reporting?

- Do a majority of today’s newspapers use objective journalism or interpretive journalism? Why might papers tend to favor one style of journalism over another?

- In what ways has watchdog journalism transformed the newspaper industry? What are the potential benefits and pitfalls of watchdog journalism?

- Explore the challenges that have arisen due to the growing number of newspaper chains in the United States.

- How has the Internet altered the way in which newspapers present news? How are print newspapers responding to the decline of subscribers and the rise of online readers?

Career Connection

Although modern print newspapers increasingly face economic challenges and have reduced the number of journalists they have on staff, career opportunities still exist in newspaper journalism. Those desiring to enter the field may need to explore new ways of approaching journalism in a transforming industry.

Read the articles “Every Newspaper Journalist Should Start a Blog,” written by Scott Karp, found at http://publishing2.com/2007/05/22/every-newspaper-journalist-should-start-a-blog/, and “Writing the Freelance Newspaper Article,” by Cliff Hightower, at http://www.fmwriters.com/Visionback/Issue32/Writefreenewspaper.htm.

Think about these two articles as you answer the following questions.

- What does Scott Karp mean when he says that a blog entails “embracing the power and accepting the responsibility of being a publisher”? What should you do on your blog to do just that?

- According to Karp, what is “the fundamental law of the web”?

- Karp lists two journalists who have shown opposition to his article. What are the criticisms or caveats to Karp’s main article that are discussed?

- Describe the three suggestions that Cliff Hightower provides when thinking about a career as a freelance writer. How might you be able to begin incorporating those suggestions into your own writing?

- What two texts does Hightower recommend as you embark on a career as a freelance writer?

References

Australian Politics, “Original Drudge Reports of Monica Lewinsky Scandal (January 17, 1998),” AustralianPolitics.com, http://australianpolitics.com/usa/clinton/impeachment/drudge.shtml.

Brown, Tina. “The Daily Beast Turns One,” Daily Beast, October 5, 2009, http://www.thedailybeast.com/blogs-and-stories/2009-10-05/the-daily-beast-turns-one/full/.

Chen, Gina. “Is Blogging Journalism?” Save the Media, March 28, 2009, http://savethemedia.com/2009/03/28/is-blogging-journalism/.

Folkenflik, “Newspapers Wade Into an Online-Only Future.”

Folkenflik, David. “Newspapers Wade Into an Online-Only Future,” NPR, March 20, 2009, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=102162128.

Huffington Post, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/.

Rosen, Jay. “Brain Food for BloggerCon,” PressThink (blog), April 16, 2004, http://journalism.nyu.edu/pubzone/weblogs/pressthink/2004/04/16/con_prelude.html.

Taylor, Alana. “What It Takes to Be a Beatblogger,” BeatBlogging.org (blog), March 5, 2009, http://beatblogging.org/2009/03/05/what-it-takes-to-be-a-beatblogger/.

Viswanathan, S. “Internet Media: Sky’s the Limit,” Hindu, March 28, 2010, http://beta.thehindu.com/opinion/Readers-Editor/article318231.ece.

Viswanathan, S. “Internet Media: Sky’s the Limit,” Hindu, March 28, 2010, http://beta.thehindu.com/opinion/Readers-Editor/article318231.ece.

Williams, Lisa. “Newspaper Chain Goes Creative Commons: GateHouse Media Rolls CC Over 96 Newspaper Sites,” PressThink (blog), December 15, 2006, http://journalism.nyu.edu/pubzone/weblogs/pressthink/2006/12/15/newspaper_chain.html.

Wyke, Nick. “Meet the Food Bloggers: Orangette,” Times (London), May 26, 2009, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/food_and_drink/real_food/article6364590.ece.

4.5 Current Popular Trends in the Newspaper Industry

Learning Objectives

- Identify newspapers with high circulations.

- Describe the decline of the newspaper industry.

Popular media such as television and the Internet have forever changed the newspaper industry. To fully understand the impact that current technology is having on the newspaper industry, it is necessary to first examine the current state of the industry.

Major Publications in the U.S. Newspaper Industry

Although numerous papers exist in the United States, a few major publications dominate circulation and, thus, exert great influence on the newspaper industry. Each of these newspapers has its own unique journalistic and editorial style, relying on different topics and techniques to appeal to its readership.

USA Today

USA Today currently tops the popularity chart with a daily circulation of 2,281,831 (Newspapers). This national paper’s easy-to-read content and visually focused layout contribute to its high readership numbers. Although the paper does not formally publish on weekends, it does have a partner paper titled USA Weekend. USA Today consists of four sections: news, money, sports, and life; for the ease of its readers, the newspaper color-codes each section. Owned by the Gannett Company, the paper caters to its audience by opting for ease of comprehension over complexity.

The Wall Street Journal

Established in the late 1800s, The Wall Street Journal closely trails USA Today, with a circulation of 2,070,498 (Newspapers). In fact, USA Today and The Wall Street Journal have competed for the top circulation spot for many years. An international paper that focuses on business and financial news, The Wall Street Journal primarily uses written narration with few images. Recent changes to its layout, such as adding advertising on the front page and minimizing the size of the paper slightly to save on printing costs, have not dramatically shifted this long-standing focus. The paper runs between 50 and 96 pages per issue and gives its readers up-to-date information on the economy, business, and national and international financial news.

The New York Times

The New York Times is another major publication, with circulation at 1,121,623 (Newspapers). Founded in 1851, the New York City–based paper is owned by the New York Times Company, which also publishes several smaller regional papers. The flagship paper contains three sections: news, opinion, and features. Although its articles tend to be narrative-driven, the paper does include images for many of its articles, creating a balance between the wordier layout of The Wall Street Journal and the highly visual USA Today. The New York Times publishes international stories along with more local stories in sections such as Arts, Theater, and Metro. The paper has also successfully established itself on the Internet, becoming one of the most popular online papers today.

Los Angeles Times

The Los Angeles Times—currently the only West Coast paper to crack the top 10 circulation list—has also contributed much to the newspaper industry. First published in 1881, the California-based paper has a distribution of 907,977 (Newspapers). Perhaps the most unique feature of the paper is its Column One, which focuses on sometimes-bizarre stories meant to engage readers. Known for its investigative journalistic approach, the Los Angeles Times demands that its journalists “provide a rich, nuanced account” of the issues they cover (Los Angeles Times, 2007). By 2010, the paper had won 39 Pulitzer Prizes, including five gold medals for public service (Los Angeles Times).

The Washington Post

First published in 1877, The Washington Post is Washington, DC’s oldest and largest paper, with a daily circulation of 709,997 (Top 10 US Newspapers by Circulation). According to its editors, the paper aims to be “fair and free and wholesome in its outlook on public affairs and public men (Washington Post).” In this vein, The Washington Post has developed a strong investigative journalism style, perhaps most exemplified by its prominent investigation of the Watergate Scandal.

The paper also holds the principle of printing articles fit “for the young as well as the old (Washington Post).” In 2003, The Washington Post launched a new section called the Sunday Source which targets the 18- to 34-year-old age group in an attempt to increase readership among younger audiences. This weekend supplement section focused on entertainment and lifestyle issues, like style, food, and fashion. Although it ceased publication in 2008, some of its regular features migrated to the regular paper. Like the Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post holds numerous Pulitzer Prizes for journalism.

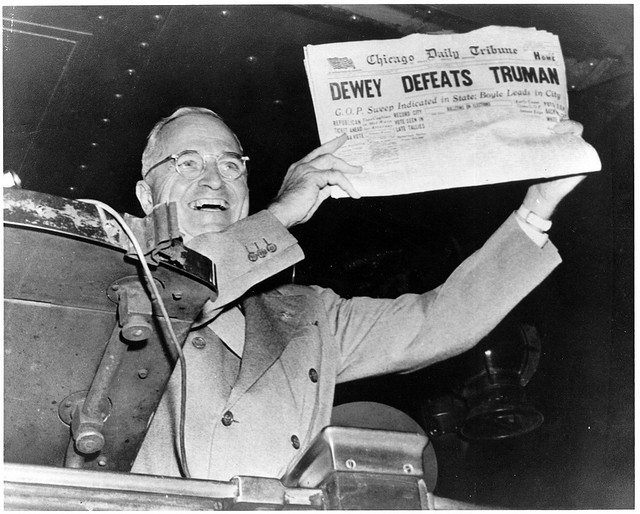

Chicago Tribune

One other major publication with a significant impact on the newspaper industry is the Chicago Tribune, wielding a circulation of 643,086. First established in 1847, the paper is often remembered for famously miscalling the 1948 presidential election with the headline of “Dewey Defeats Truman.”

Despite this error, the Chicago Tribune has become known for its watchdog journalism, including a specific watchdog section for issues facing Chicago, like pollution, politics, and more. It proudly proclaims its commitment “to standing up for your interests and serving as your watchdog in the corridors of power (Chicago Tribune).”

Dave Winer – Dewey Defeats Truman – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Declining Readership and Decreasing Revenues

Despite major newspapers’ large circulations, newspapers as a whole are experiencing a dramatic decline in both subscribers and overall readership. For example, on February 27, 2009, Denver’s Rocky Mountain News published its final issue after nearly 150 years in print. The front-page article “Goodbye, Colorado” reflected on the paper’s long-standing history with the Denver community, observing that “It is with great sadness that we say goodbye to you today. Our time chronicling the life of Denver and Colorado, the nation and the world, is over (Rocky Mountain News, 2009).”

Readership Decline

The story of Rocky Mountain News is neither unique nor entirely unexpected. For nearly a half-century, predictions of the disappearance of print newspapers have been an ongoing refrain. The fear of losing print media began in the 1940s with the arrival of the radio and television. Indeed, the number of daily papers has steadily decreased since the 1940s; in 1990, the number of U.S. dailies was just 1,611. By 2008, that number had further shrunk to 1,408 (Newspaper Association of America). But the numbers are not as clear-cut as they appear. As one report observed, “The root problems go back to the late 1940s, when the percentage of Americans reading newspapers began to drop. But for years the U.S. population was growing so much that circulation kept rising and then, after 1970s, remained stable (State of the Media, 2004).” During the 1970s when circulation stopped rising, more women were entering the workforce. By the 1990s when “circulation began to decline in absolute numbers,” the number of women in the workforce was higher than had ever been previously experienced (State of the Media, 2004). With women at work, there were fewer people at home with leisure time for reading daily papers for their news. This, combined with television journalism’s rising popularity and the emergence of the Internet, meant a significant decrease in newspaper circulation. With newer, more immediate ways to get news, the disconnect between newspapers and consumers deepened.

Compounding the problem is newspapers’ continuing struggle to attract younger readers. Many of these young readers simply did not grow up in households that subscribed to daily papers and so they do not turn to newspapers for information. However, the problem seems to be more complex “than fewer people developing the newspaper habit. People who used to read every day now read less often. Some people who used to read a newspaper have stopped altogether (State of the Media, 2004).”

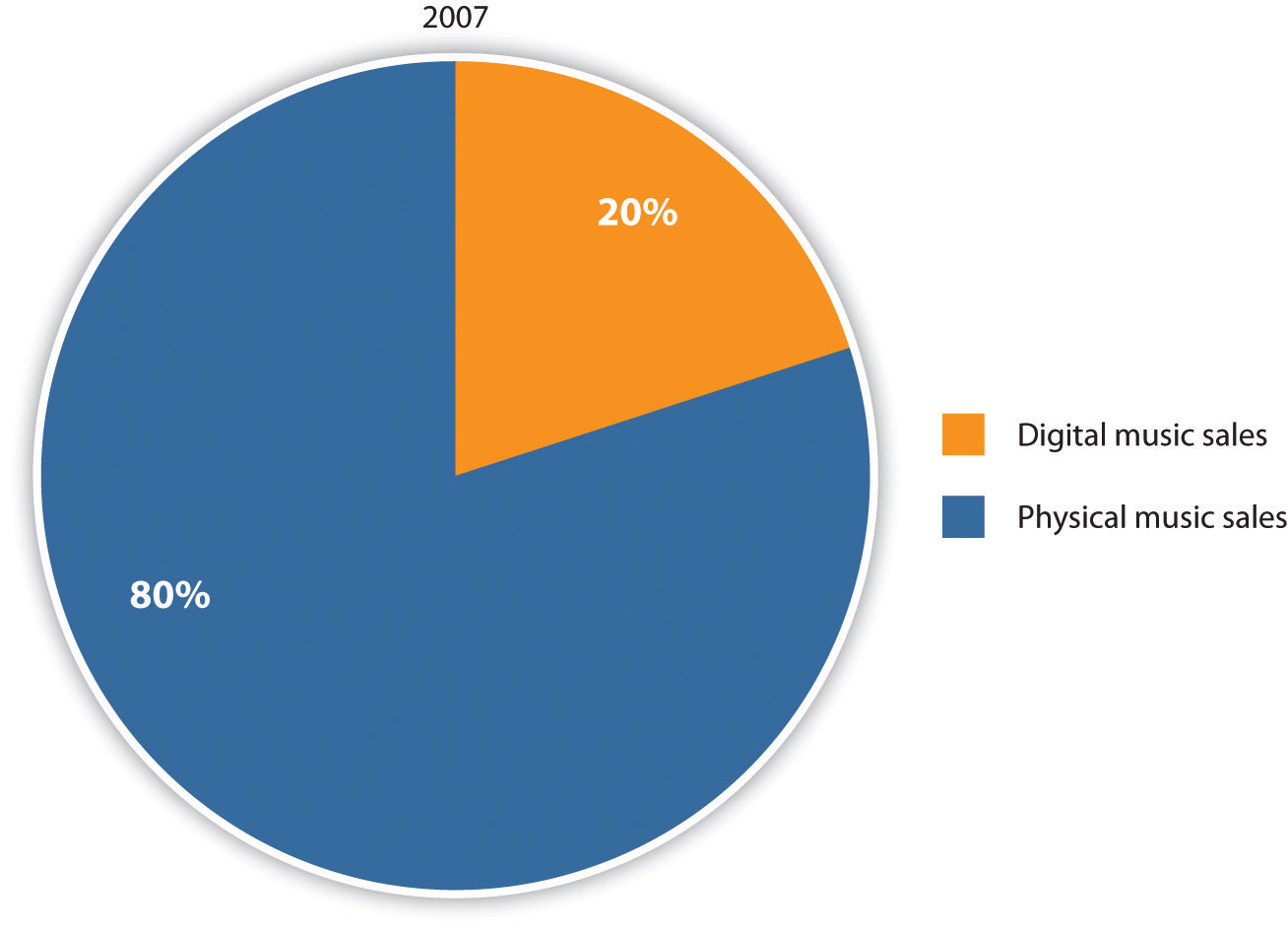

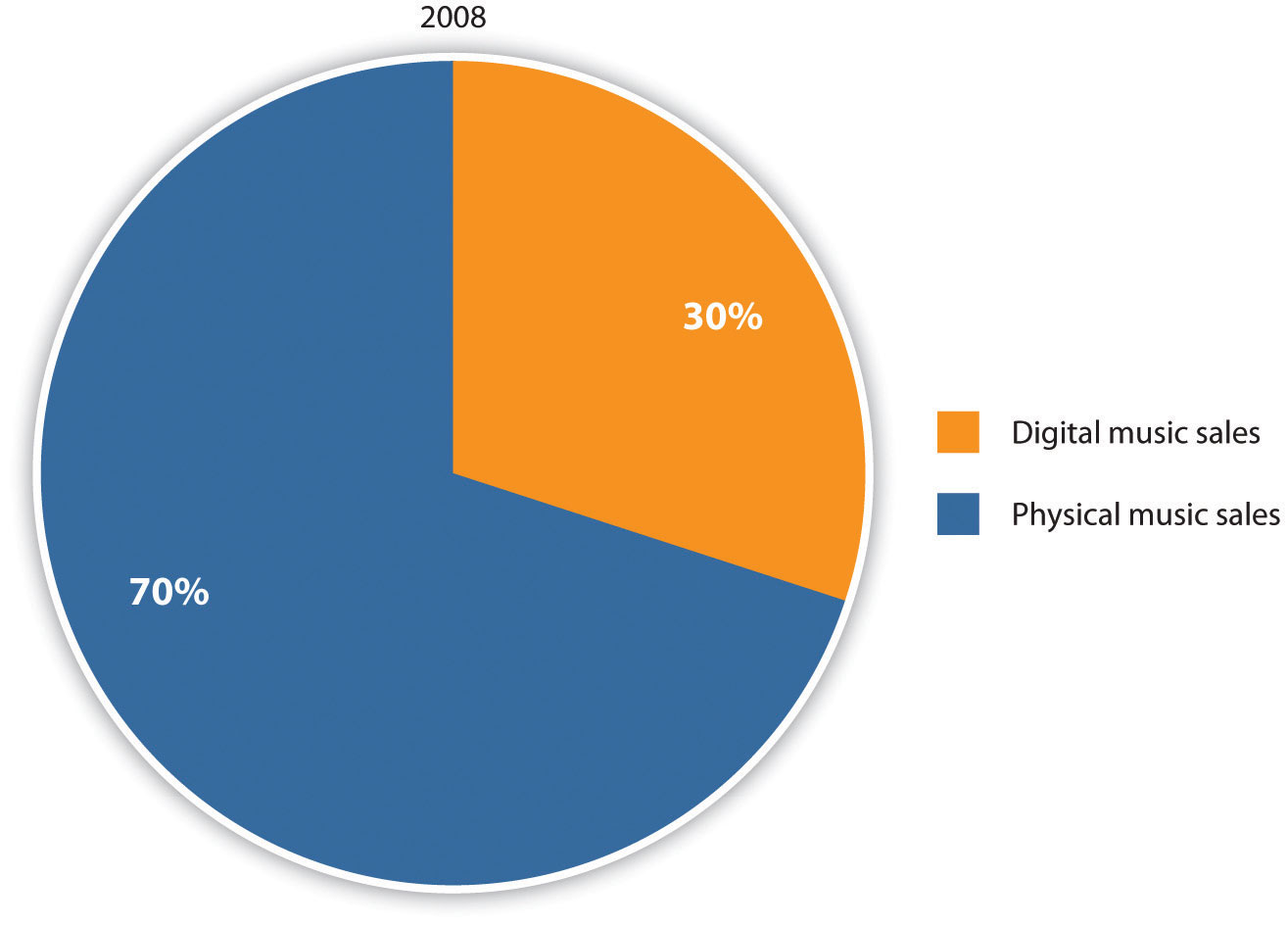

Yet the most significant challenge to newspapers is certainly the Internet. As print readership declines, online readership has grown; fast, free access to breaking information contributes to the growing appeal of online news. Despite the increase in online news readers, that growth has not offset the drop in print readership. In 2008, the Pew Research Center conducted a news media consumption survey in which only

39 percent of participants claimed to having read a newspaper (either print or online) the day before, showing a drop from 43 percent in 2006. Meanwhile, readership of print newspapers fell from 34 percent to 25 percent in that time period (Dilling, 2009).

The study also observed that younger generations are primarily responsible for this shift to online reading. “The changes in reader habits seem to be similar amongst both Generation X and Y demographics, where marked increases in consulting online news sources were observed (Dilling, 2009).” Baby boomers and older generations do, for the most part, still rely on printed newspapers for information. Perhaps this distinction between generations is not surprising. Younger readers grew up with the Internet and have developed different expectations about the speed, nature, and cost of information than have older generations. However, this trend suggests that online readership along with the general decline of news readers may make printed newspapers all but obsolete in the near future.

Joint Operating Agreements

As readership began to decline in the 1970s and newspapers began experiencing greater competition within individual cities, Congress issued the Newspaper Preservation Act authorizing the structure of joint operating agreements (JOAs). The implementation of JOAs means that two newspapers could “share the cost of business, advertising, and circulation operations,” which helped newspapers stay afloat in the face of an ever-shrinking readership (Milstead, 2009). The Newspaper Preservation Act also ensured that two competing papers could keep their distinct news divisions but merge their business divisions.

At its peak, 28 newspaper JOAs existed across the United States, but as the industry declines at an increasingly rapid rate, JOAs are beginning to fail. With today’s shrinking pool of readers, two newspapers simply cannot effectively function in one community. In 2009, only nine JOAs continued operations, largely because JOAs “don’t eliminate the basic problem of one newspaper gaining the upper hand in circulation and, hence, advertising revenue (Milstead, 2009).” With advertising playing a key role in newspapers’ financial survival, revenue loss is a critical blow. Additionally, “in recent years, of course, the Internet has thrown an even more dramatic wrench into the equation. Classified advertising has migrated to Internet sites like craigslist.org while traditional retail advertisers…can advertise via their own web sites (Milstead, 2009).” As more advertisers move away from the newspaper industry, more JOAs will likely crumble. The destruction of JOAs will, in turn, result in the loss of more newspapers.

Newspaper Chains

As newspapers diminish in number and as newspaper owners find themselves in financial trouble, a dramatic increase in the consolidation of newspaper ownership has taken place. Today, many large companies own several papers across the country, buying independently owned papers to help them stay afloat. The change has been occurring for some time; in fact, “since 1975, more than two-thirds of independently owned newspapers…have disappeared (Free Press).” However, since 2000, newspaper consolidation has increased markedly as more papers are turning over control to larger companies.

In 2002, the 22 largest newspaper chains owned 39 percent of all the newspapers in the country (562 papers). Yet those papers represent 70 percent of daily circulation and 73 percent of Sunday. And their influence appears to be growing. These circulation percentages are a full percentage point higher than 2001 (State of the Media, 2004).

Among the 22 companies that own the largest percentage of the papers, four chains stand out: Gannett, the Tribune Company, the New York Times Company, and the McClatchy Company. Not only do these companies each own several papers across the country, but they also enjoy a higher-than-normal profit margin relative to smaller chains.

Recent Ownership Trends

In addition to consolidation, the decline of print newspapers has brought about several changes in ownership as companies attempt to increase their revenue. In 2007, media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation purchased The Wall Street Journal with an unsolicited $5 billion bid, promising to “pour money into the Journal and its website and use his satellite television networks in Europe and Asia to spread Journal content the world over (Ahrens, 2007).” Murdoch has used the buyout to move the paper into the technological world, asking readers and newspapers to embrace change. In 2009, he published an article in The Wall Street Journal assuring his readers that “the future of journalism is more promising than ever—limited only by editors and producers unwilling to fight for their readers and viewers, or government using its heavy hand either to overregulate or subsidize us (Murdoch, 2009).” Murdoch believes that the hope of journalism lies in embracing the changing world and how its inhabitants receive news. Time will tell if he is correct.

Despite changes in power, the consolidation trend is leveling off. Even large chains must cut costs to avoid shuttering papers entirely. In January 2009, the newspaper industry experienced 2,252 layoffs; in total, the U.S. newspaper industry lost 15,114 jobs that year (Murdoch, 2009). With the dual challenges of layoffs and decreasing readership, some in the journalism industry are beginning to explore other options for ownership, such as nonprofit ownership. As one article in the Chronicle of Philanthropy puts it, “It may be time for a more radical reinvention of the daily newspaper. The answer for some newspapers may be to adopt a nonprofit ownership structure that will enable them to seek philanthropic contributions and benefit from tax exemptions (Stehle, 2009).”

It is clear that the newspaper industry is on the brink of major change. Over the next several years, the industry will likely continue to experience a complete upheaval brought on by dwindling readership and major shifts in how individuals consume news. As newspapers scramble to find their footing in an ever-changing business, readers adapt and seek out trustworthy information in new ways.

Key Takeaways

- Some key players in the U.S. newspaper market include the USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and the Chicago Tribune.

- Although readership has been declining since the invention of the radio, the Internet has had the most profound effect on the newspaper industry as readers turn to free online sources of information.

- Financial challenges have led to the rise of ever-growing newspaper chains and the creation of JOAs. Nevertheless, newspapers continue to fold and lay off staff.

Exercises

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Pick a major national event that interests you. Then, select two papers of the six discussed in this section and explore the differences in how those newspapers reported on the story. How does the newspaper’s audience affect the way in which a story is presented?

- Spend some time exploring websites of several major newspapers. How have these papers been responding to growing online readership?

References

Ahrens, Frank. “Murdoch Seizes Wall St. Journal in $5 Billion Coup,” Washington Post, August 1, 2007, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/07/31/AR2007073100896.html.

Chicago Tribune, “On Guard for Chicago,” http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/chi-on-guard-for-chicago,0,3834517.htmlpage.

Dilling, Emily. “Study: Newspaper Readership Down, Despite Online Increase,” Shaping the Future of the Newspaper (blog), March 3, 2009, http://www.sfnblog.com/circulation_and_readership/2009/03/study_newspaper_readership_down_despite.php.

Free Press, “Media Consolidation,” http://www.freepress.net/policy/ownership/consolidation.

Los Angeles Times, “L.A. Times Ethics Guidelines,” Readers’ Representative Journal (blog), http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/readers/2007/07/los-angeles-tim.html.

Los Angeles Times, “Times’ Pulitzer Prizes,” http://www.latimes.com/about/mediagroup/latimes/la-mediagroup-pulitzers,0,1929905.htmlstory.

Milstead, David. “Newspaper Joint Operating Agreements Are Fading,” Rocky Mountain News, January 22, 2009, http://www.rockymountainnews.com/news/2009/jan/22/newspaper-joas-fading/.

Murdoch, Rupert. “Journalism and Freedom,” Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704107104574570191223415268.html.

Newspaper Association of American, “Total Paid Circulation,” http://www.naa.org/TrendsandNumbers/Total-Paid-Circulation.aspx.

Newspaper, “Top 10 US Newspapers by Circulation,” Newspapers.com, http://www.newspapers.com/top10.html.

Rocky Mountain News, “Goodbye, Colorado,” February 7, 2009, http://www.rockymountainnews.com/news/2009/feb/27/goodbye-colorado/.

State of the Media, project for Excellence in Journalism, “Newspapers: Audience” in The State of the News Media 2004, http://www.stateofthemedia.org/2004/narrative_newspapers_audience.asp?cat=3&media=2.

State of the Media, project for Excellence in Journalism, “Newspapers: Ownership” in The State of the News Media 2004, http://www.stateofthemedia.org/2004/narrative_newspapers_ownership.asp?cat=5&media=2.

Stehle, Vince. “It’s Time for Newspapers to Become Nonprofit Organizations,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, March 12, 2009, http://gfem.org/node/492.

Washington Post, “General Information: Post Principles,” https://nie.washpost.com/gen_info/principles/index.shtml.

4.3 Different Styles and Models of Journalism

Learning Objectives

- Explain how objective journalism differs from story-driven journalism.

- Describe the effect of objectivity on modern journalism.

- Describe the unique nature of literary journalism.

Location, readership, political climate, and competition all contribute to rapid transformations in journalistic models and writing styles. Over time, however, certain styles—such as sensationalism—have faded or become linked with less serious publications, like tabloids, while others have developed to become prevalent in modern-day reporting. This section explores the nuanced differences among the most commonly used models of journalism.

Objective versus Story-Driven Journalism

In the late 1800s, a majority of publishers believed that they would sell more papers by reaching out to specific groups. As such, most major newspapers employed a partisan approach to writing, churning out political stories and using news to sway popular opinion. This all changed in 1896 when a then-failing paper, The New York Times, took a radical new approach to reporting: employing objectivity, or impartiality, to satisfy a wide range of readers.

The Rise of Objective Journalism

At the end of the 19th century, The New York Times found itself competing with the papers of Pulitzer and Hearst. The paper’s publishers discovered that it was nearly impossible to stay afloat without using the sensationalist headlines popularized by its competitors. Although The New York Times publishers raised prices to pay the bills, the higher charge led to declining readership, and soon the paper went bankrupt. Adolph Ochs, owner of the once-failing Chattanooga Times, took a gamble and bought The New York Times in 1896. On August 18 of that year, Ochs made a bold move and announced that the paper would no longer follow the sensationalist style that made Pulitzer and Hearst famous, but instead would be “clean, dignified, trustworthy and impartial (New York Times, 1935).”

This drastic change proved to be a success. The New York Times became the first of many papers to demonstrate that the press could be “economically as well as ethically successful (New York Times, 1935).” With the help of managing editor Carr Van Anda, the new motto “All the News That’s Fit to Print,” and lowered prices, The New York Times quickly turned into one of the most profitable impartial papers of all time. Since the newspaper’s successful turnaround, publications around the world have followed The New York Times’ objective journalistic style, demanding that reporters maintain a neutral voice in their writing.

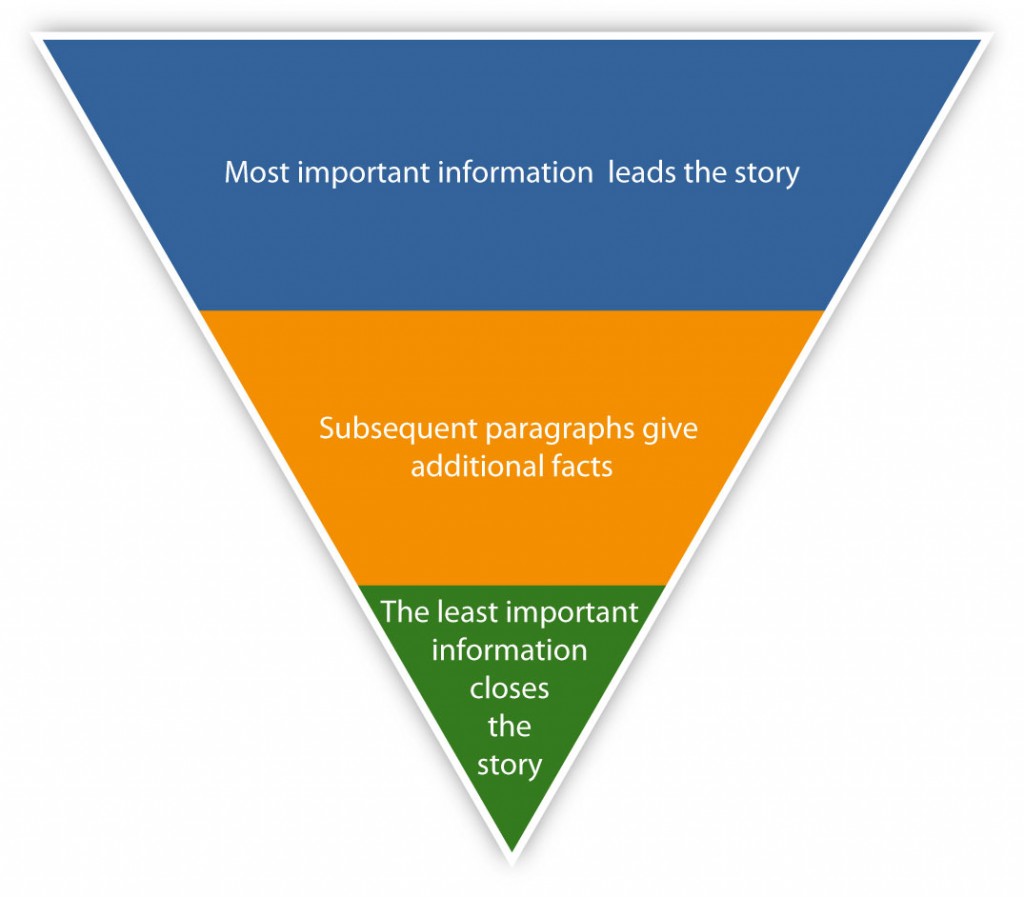

The Inverted Pyramid Style

One commonly employed technique in modern journalism is the inverted pyramid style. This style requires objectivity and involves structuring a story so that the most important details are listed first for ease of reading. In the inverted pyramid format, the most fundamental facts of a story—typically the who, what, when, where, and why—appear at the top in the lead paragraph, with nonessential information in subsequent paragraphs. The style arose as a product of the telegraph. The inverted pyramid proved useful when telegraph connections failed in the middle of transmission; the editor still had the most important information at the beginning. Similarly, editors could quickly delete content from the bottom up to meet time and space requirements (Scanlan, 2003).

The reason for such writing is threefold. First, the style is helpful for writers, as this type of reporting is somewhat easier to complete in the short deadlines imposed on journalists, particularly in today’s fast-paced news business. Second, the style benefits editors who can, if necessary, quickly cut the story from the bottom without losing vital information. Finally, the style keeps in mind traditional readers, most of who skim articles or only read a few paragraphs, but they can still learn most of the important information from this quick read.

Interpretive Journalism

During the 1920s, objective journalism fell under critique as the world became more complex. Even though The New York Times continued to thrive, readers craved more than dry, objective stories. In 1923, Time magazine launched as the first major publication to step away from simple objectivity to try to provide readers with a more analytical interpretation of the news. As Time grew, people at some other publications took notice, and slowly editors began rethinking how they might reach out to readers in an increasingly interrelated world.

During the 1930s, two major events increased the desire for a new style of journalism: the Great Depression and the Nazi threat to global stability. Readers were no longer content with the who, what, where, when, and why of objective journalism. Instead, they craved analysis and a deeper explanation of the chaos surrounding them. Many papers responded with a new type of reporting that became known as interpretive journalism.

Interpretive journalism, following Time’s example, has grown in popularity since its inception in the 1920s and 1930s, and journalists use it to explain issues and to provide readers with a broader context for the stories that they encounter. According to Brant Houston, the executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors Inc., an interpretive journalist “goes beyond the basic facts of an event or topic to provide context, analysis, and possible consequences (Houston, 2008).” When this new style was first used, readers responded with great interest to the new editorial perspectives that newspapers were offering on events. But interpretive journalism posed a new problem for editors: the need to separate straight objective news from opinions and analysis. In response, many papers in the 1930s and 1940s “introduced weekend interpretations of the past week’s events…and interpretive columnists with bylines (Ward, 2008).” As explained by Stephen J. A. Ward in his article, “Journalism Ethics,” the goal of these weekend features was to “supplement objective reporting with an informed interpretation of world events (Ward, 2008).”

Competition From Broadcasting

The 1930s also saw the rise of broadcasting as radios became common in most U.S. households and as sound–picture recordings for newsreels became increasingly common. This broadcasting revolution introduced new dimensions to journalism. Scholar Michael Schudson has noted that broadcast news “reflect[ed]…a new journalistic reality. The journalist, no longer merely the relayer of documents and messages, ha[d] become the interpreter of the news (Schudson, 1982).” However, just as radio furthered the interpretive journalistic style, it also created a new problem for print journalism, particularly newspapers.

Suddenly, free news from the radio offered competition to the pay news of newspapers. Scholar Robert W. McChesney has observed that, in the 1930s, “many elements of the newspaper industry opposed commercial broadcasting, often out of fear of losing ad revenues and circulation to the broadcasters (McChesney, 1992).” This fear led to a media war as papers claimed that radio was stealing their print stories. Radio outlets, however, believed they had equal right to news stories. According to Robert W. McChesney, “commercial broadcasters located their industry next to the newspaper industry as an icon of American freedom and culture (McChesney, 1992).” The debate had a major effect on interpretive journalism as radio and newspapers had to make decisions about whether to use an objective or interpretive format to remain competitive with each other.

The emergence of television during the 1950s created even more competition for newspapers. In response, paper publishers increased opinion-based articles, and many added what became known as op-ed pages. An op-ed page—short for opposite the editorial page—features opinion-based columns typically produced by a writer or writers unaffiliated with the paper’s editorial board. As op-ed pages grew, so did interpretive journalism. Distinct from news stories, editors and columnists presented opinions on a regular basis. By the 1960s, the interpretive style of reporting had begun to replace the older descriptive style (Patterson, 2002).

Literary Journalism

Stemming from the development of interpretive journalism, literary journalism began to emerge during the 1960s. This style, made popular by journalists Tom Wolfe (formerly a strictly nonfiction writer) and Truman Capote, is often referred to as new journalism and combines factual reporting with sometimes fictional narration. Literary journalism follows neither the formulaic style of reporting of objective journalism nor the opinion-based analytical style of interpretive journalism. Instead, this art form—as it is often termed—brings voice and character to historical events, focusing on the construction of the scene rather than on the retelling of the facts.

Important Literary Journalists

Figure 4.9

The works of Tom Wolfe are some of the best examples of literary journalism of the 1960s.

erin williamson – tom wolfe – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Tom Wolfe was the first reporter to write in the literary journalistic style. In 1963, while his newspaper, New York’s Herald Tribune, was on strike, Esquire magazine hired Wolfe to write an article on customized cars. Wolfe gathered the facts but struggled to turn his collected information into a written piece. His managing editor, Byron Dobell, suggested that he type up his notes so that Esquire could hire another writer to complete the article. Wolfe typed up a 49-page document that described his research and what he wanted to include in the story and sent it to Dobell. Dobell was so impressed by this piece that he simply deleted the “Dear Byron” at the top of the letter and published the rest of Wolfe’s letter in its entirety under the headline “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.” The article was a great success, and Wolfe, in time, became known as the father of new journalism. When he later returned to work at the Herald Tribune, Wolfe brought with him this new style, “fusing the stylistic features of fiction and the reportorial obligations of journalism (Kallan, 1992).”

Truman Capote responded to Wolfe’s new style by writing In Cold Blood, which Capote termed a “nonfiction novel,” in 1966 (Plimpton, 1966). The tale of an actual murder that had taken place on a Kansas farm some years earlier, the novel was based on numerous interviews and painstaking research. Capote claimed that he wrote the book because he wanted to exchange his “self-creative world…for the everyday objective world we all inhabit (Plimpton, 1966).” The book was praised for its straightforward, journalistic style. New York Times writer George Plimpton claimed that the book “is remarkable for its objectivity—nowhere, despite his involvement, does the author intrude (Plimpton, 1966).” After In Cold Blood was finished, Capote criticized Wolfe’s style in an interview, commenting that Wolfe “[has] nothing to do with creative journalism,” by claiming that Wolfe did not have the appropriate fiction-writing expertise (Plimpton, 1966). Despite the tension between these two writers, today they are remembered for giving rise to a similar style in varying genres.

The Effects of Literary Journalism

Although literary journalism certainly affected newspaper reporting styles, it had a much greater impact on the magazine industry. Because they were bound by fewer restrictions on length and deadlines, magazines were more likely to publish this new writing style than were newspapers. Indeed, during the 1960s and 1970s, authors simulating the styles of both Wolfe and Capote flooded magazines such as Esquire and The New Yorker with articles.

Literary journalism also significantly influenced objective journalism. Many literary journalists believed that objectivity limited their ability to critique a story or a writer. Some claimed that objectivity in writing is impossible, as all journalists are somehow swayed by their own personal histories. Still others, including Wolfe, argued that objective journalism conveyed a “limited conception of the ‘facts,’” which “often effected an inaccurate, incomplete story that precluded readers from exercising informed judgment (Kallan).”

Advocacy Journalism and Precision Journalism

The reactions of literary journalists to objective journalism encouraged the growth of two more types of journalism: advocacy journalism and precision journalism. Advocacy journalists promote a particular cause and intentionally adopt a biased, nonobjective viewpoint to do so effectively. However, serious advocate journalists adhere to strict guidelines, as “an advocate journalist is not the same as being an activist” according to journalist Sue Careless (Careless, 2000). In an article discussing advocacy journalism, Careless contrasted the role of an advocate journalist with the role of an activist. She encourages future advocate journalists by saying the following:

A journalist writing for the advocacy press should practice the same skills as any journalist. You don’t fabricate or falsify. If you do you will destroy the credibility of both yourself as a working journalist and the cause you care so much about. News should never be propaganda. You don’t fudge or suppress vital facts or present half-truths (Careless, 2000).

Despite the challenges and potential pitfalls inherent to advocacy journalism, this type of journalism has increased in popularity over the past several years. In 2007, USA Today reporter Peter Johnson stated, “Increasingly, journalists and talk-show hosts want to ‘own’ a niche issue or problem, find ways to solve it, and be associated with making this world a better place (Johnson, 2007).” In this manner, journalists across the world are employing the advocacy style to highlight issues they care about.

Oprah Winfrey: Advocacy Journalist

Television talk-show host and owner of production company Harpo Inc., Oprah Winfrey is one of the most successful, recognizable entrepreneurs of the late-20th and early-21st centuries. Winfrey has long been a news reporter, beginning in the late 1970s as a coanchor of an evening television program. She began hosting her own show in 1984, and in 2010, the Oprah Winfrey Show was one of the most popular TV programs on the air. Winfrey had long used her show as a platform for issues and concerns, making her one of the most famous advocacy journalists. While many praise Winfrey for using her celebrity to draw attention to causes she cares about, others criticize her techniques, claiming that she uses the advocacy style for self-promotion. As one critic writes, “I’m not sure how Oprah’s endless self-promotion of how she spent millions on a school in South Africa suddenly makes her ‘own’ the ‘education niche.’ She does own the trumpet-my-own-horn niche. But that’s not ‘journalism (Schlussel, 2007).’”

Yet despite this somewhat harsh critique, many view Winfrey as the leading example of positive advocacy journalism. Sara Grumbles claims in her blog “Breaking and Fitting the Mold”: “Oprah Winfrey obviously practices advocacy journalism…. Winfrey does not fit the mold of a ‘typical’ journalist by today’s standards. She has an agenda and she voices her opinions. She ha[d] her own op-ed page in the form of a million dollar television studio. Objectivity is not her strong point. Still, in my opinion she is a journalist (Grumbles, 2007).”

Regardless of the arguments about the value and reasoning underlying her technique, Winfrey unquestionably practices a form of advocacy journalism. In fact, thanks to her vast popularity, she may be the most compelling example of an advocacy journalist working today.

Precision journalism emerged in the 1970s. In this form, journalists turn to polls and studies to strengthen the accuracy of their articles. Philip Meyer, commonly acknowledged as the father of precision journalism, says that his intent is to “encourage my colleagues in journalism to apply the principles of scientific method to their tasks of gathering and presenting the news (Meyer, 2002).” This type of journalism adds a new layer to objectivity in reporting, as articles no longer need to rely solely on anecdotal evidence; journalists can employ hard facts and figures to support their assertions. An example of precision journalism would be an article on voting patterns in a presidential election that cites data from exit polls. Precision journalism has become more popular as computers have become more prevalent. Many journalists currently use this type of writing.

Consensus versus Conflict Newspapers

Another important distinction within the field of journalism must be made between consensus journalism and conflict journalism. Consensus journalism typically takes place in smaller communities, where local newspapers generally serve as a forum for many different voices. Newspapers that use consensus-style journalism provide community calendars and meeting notices and run articles on local schools, events, government, property crimes, and zoning. These newspapers can help build civic awareness and a sense of shared experience and responsibility among readers in a community. Often, business or political leaders in the community own consensus papers.

Conversely, conflict journalism, like that which is presented in national and international news articles in The New York Times, typically occurs in national or metropolitan dailies. Conflict journalists define news in terms of societal discord, covering events and issues that contravene perceived social norms. In this style of journalism, reporters act as watchdogs who monitor the government and its activities. Conflict journalists often present both sides of a story and pit ideas against one another to generate conflict and, therefore, attract a larger readership. Both conflict and consensus papers are widespread. However, because they serve different purposes and reach out to differing audiences, they largely do not compete with each other.

Niche Newspapers

Niche newspapers represent one more model of newspapers. These publications, which reach out to a specific target group, are rising in popularity in the era of Internet. As Robert Courtemanche, a certified journalism educator, writes, “In the past, newspapers tried to be everything to every reader to gain circulation. That outdated concept does not work on the Internet where readers expect expert, niche content (Courtemanche, 2008).” Ethnic and minority papers are some of the most common forms of niche newspapers. In the United States—particularly in large cities such as New York—niche papers for numerous ethnic communities flourish. Some common types of U.S. niche papers are papers that cater to a specific ethnic or cultural group or to a group that speaks a particular language. Papers that cover issues affecting lesbians, gay men, and bisexual individuals—like the Advocate—and religion-oriented publications—like The Christian Science Monitor—are also niche papers.

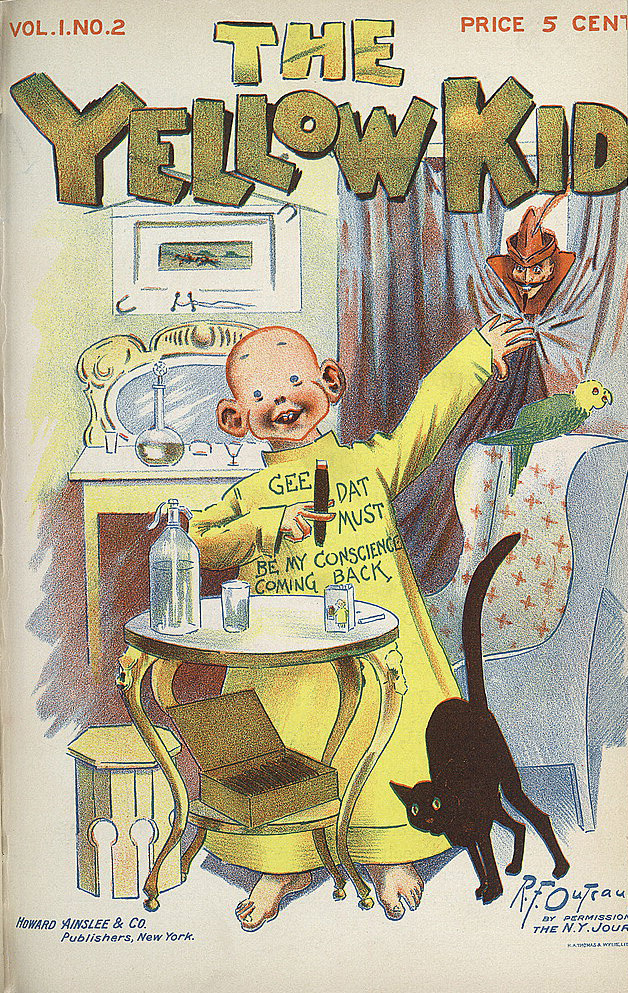

The Underground Press

Some niche papers are part of the underground press. Popularized in the 1960s and 1970s as individuals sought to publish articles documenting their perception of social tensions and inequalities, the underground press typically caters to alternative and countercultural groups. Most of these papers are published on small budgets. Perhaps the most famous underground paper is New York’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Village Voice. This newspaper was founded in 1955 and declares its role in the publishing industry by saying:

The Village Voice introduced free-form, high-spirited and passionate journalism into the public discourse. As the nation’s first and largest alternative newsweekly, the Voice maintains the same tradition of no-holds-barred reporting and criticism it first embraced when it began publishing fifty years ago (Village Voice).

Despite their at-times shoestring budgets, underground papers serve an important role in the media. By offering an alternative perspective to stories and by reaching out to niche groups through their writing, underground-press newspapers fill a unique need within the larger media marketplace. As journalism has evolved over the years, newspapers have adapted to serve the changing demands of readers.

Key Takeaways

- Objective journalism began as a response to sensationalism and has continued in some form to this day. However, some media observers have argued that it is nearly impossible to remain entirely objective while reporting a story. One argument against objectivity is that journalists are human and are, therefore, biased to some degree. Many newspapers that promote objectivity put in place systems to help their journalists remain as objective as possible.

- Literary journalism combines the research and reporting of typical newspaper journalism with the writing style of fiction. While most newspaper journalists focus on facts, literary journalists tend to focus on the scene by evoking voices and characters inhabiting historical events. Famous early literary journalists include Tom Wolfe and Truman Capote.

- Other journalistic styles allow reporters and publications to narrow their editorial voice. Advocacy journalists encourage readers to support a particular cause. Consensus journalism encourages social and economic harmony, while conflict journalists present information in a way that focuses on views outside of the social norm.

- Niche newspapers—such as members of the underground press and those serving specific ethnic groups, racial groups, or speakers of a specific language—serve as important media outlets for distinct voices. The rise of the Internet and online journalism has brought niche newspapers more into the mainstream.

Exercises

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Find an objective newspaper article that includes several factual details. Rewrite the story in a literary journalistic style. How does the story differ from one genre to the other?

- Was it difficult to transform an objective story into a piece of literary journalism? Explain.

- Do you prefer reading an objective journalism piece or a literary journalism piece? Explain.

References

Careless, Sue. “Advocacy Journalism,” Interim, May 2000, http://www.theinterim.com/2000/may/10advocacy.html.

Courtemanche, Robert. “Newspapers Must Find Their Niche to Survive,” Suite101.com, December 20, 2008, http://newspaperindustry.suite101.com/article.cfm/newspapers_must_find_their_niche_to_survive.

Grumbles, Sara. “Breaking and Fitting the Mold,” Media Chatter (blog), October 3, 2007, http://www.commajor.com/?p=1244.

Houston, Brant. “Interpretive Journalism,” The International Encyclopedia of Communication, 2008, http://www.blackwellreference.com/public/tocnode?id=g9781405131995_chunk_g978140513199514_ss82-1.

Johnson, Peter. “More Reporters Embrace an Advocacy Role,” USA Today, March 5, 2007, http://www.usatoday.com/life/television/news/2007-03-05-social-journalism_N.htm.

Kallan, Richard A. “Tom Wolfe.”

Kallan, Richard K. “Tom Wolfe,” in A Sourcebook of American Literary Journalism: Representative Writers in an Emerging Genre, ed. Thomas B. Connery (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 1992).

McChesney, Robert W. “Media and Democracy: The Emergence of Commercial Broadcasting in the United States, 1927–1935,” in “Communication in History: The Key to Understanding” OAH Magazine of History 6, no. 4 (1992): 37.

Meyer, Phillip. Precision Journalism: A Reporter’s Introduction to Social Science Methods, 4th ed. (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002), vii.

New York Times, “Adolph S. Ochs Dead at 77; Publisher of Times Since 1896,” New York Times, April 9, 1935, http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0312.html.

Patterson, Thomas. “Why Is News So Negative These Days?” History News Network, 2002, http://hnn.us/articles/1134.html.

Plimpton, George. “The Story Behind a Nonfiction Novel,” New York Times, January 16, 1966, http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/capote-interview.html.

Scanlan, Chip. “Writing from the Top Down: Pros and Cons of the Inverted Pyramid,” Poynter, June 20, 2003, http://www.poynter.org/how-tos/newsgathering-storytelling/chip-on-your-shoulder/12754/writing-from-the-top-down-pros-and-cons-of-the-inverted-pyramid/.

Schlussel, Debbie. “USA Today Heralds ‘Oprah Journalism,’” Debbie Schlussel (blog), March 6, 2007, http://www.debbieschlussel.com/497/usa-today-heralds-oprah-journalism/.

Schudson, Michael. “The Politics of Narrative Form: The Emergence of News Conventions in Print and Television,” in “Print Culture and Video Culture,” Daedalus 111, no. 4 (1982): 104.

Village Voice, “About Us,” http://www.villagevoice.com/about/index.

Ward, Stephen J. A. “Journalism Ethics,” in The Handbook of Journalism Studies, ed. Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch (New York: Routledge, 2008): 298.

4.2 History of Newspapers

Learning Objectives

- Describe the historical roots of the modern newspaper industry.

- Explain the effect of the penny press on modern journalism.

- Define sensationalism and yellow journalism as they relate to the newspaper industry.

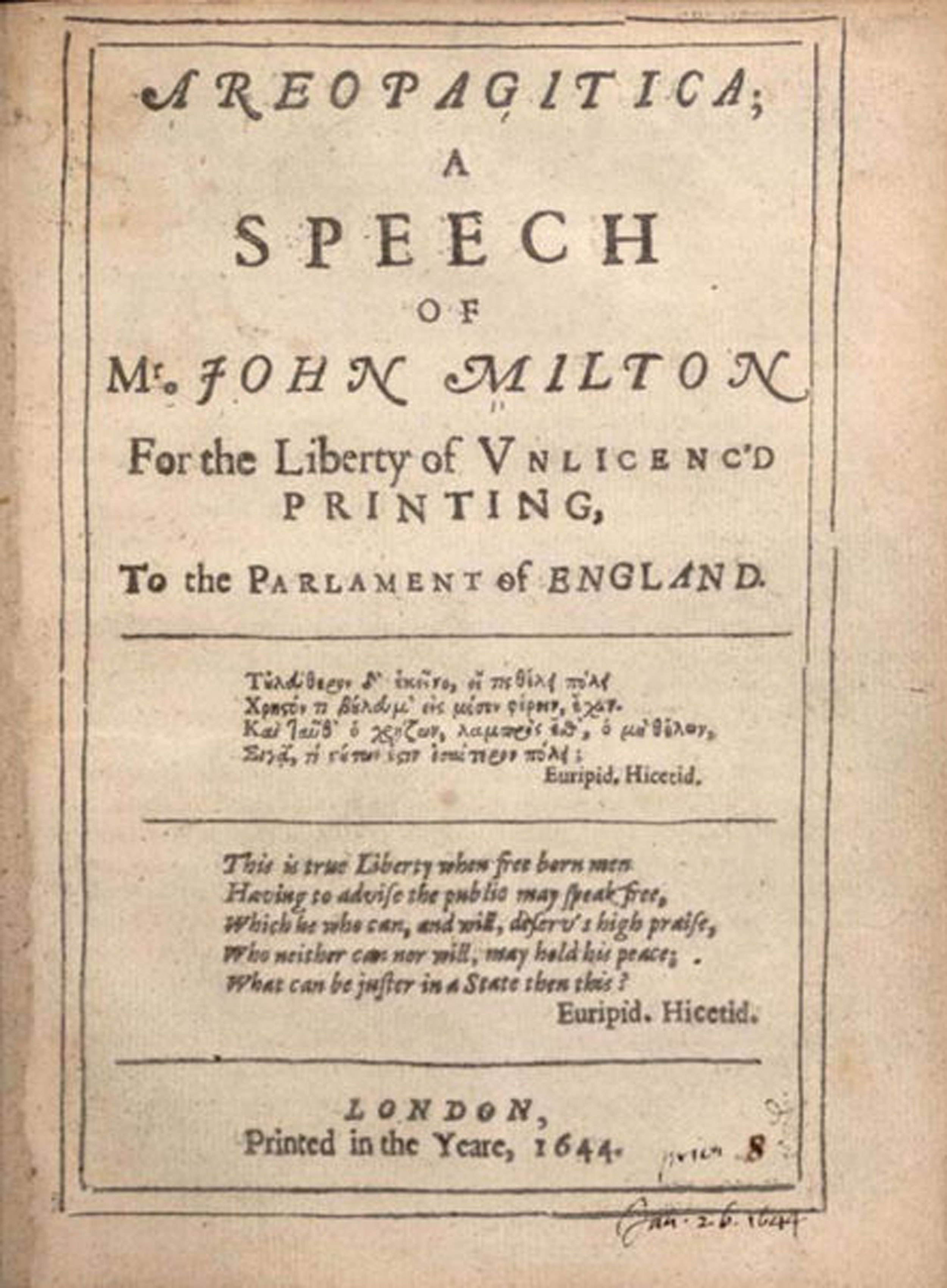

Over the course of its long and complex history, the newspaper has undergone many transformations. Examining newspapers’ historical roots can help shed some light on how and why the newspaper has evolved into the multifaceted medium that it is today. Scholars commonly credit the ancient Romans with publishing the first newspaper, Acta Diurna, or daily doings, in 59 BCE. Although no copies of this paper have survived, it is widely believed to have published chronicles of events, assemblies, births, deaths, and daily gossip.