Source Edition – Chapters 10-12

Chapter 10: Electronic Games and Entertainment

10.1 Electronic Games and Entertainment

10.2 The Evolution of Electronic Games

10.3 Influential Contemporary Games

10.4 The Impact of Video Games on Culture

10.5 Controversial Issues

10.6 Blurring the Boundaries Between Video Games, Information, Entertainment, and Communication

10.1 Electronic Games and Entertainment

Want to Get Away?

Anders Adermark – Playing – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Video games have come a long way from using a simple joystick to guide Pac-Man on his mission to find food and avoid ghosts. This is illustrated by a 2007 Southwest Airlines commercial in which two friends are playing a baseball video game on a Nintendo Wii–like console. The batting friend tells the other to throw his pitch—and he does, excitedly firing his controller into the middle of the plasma TV, which then falls off the wall. Both friends stare in shock at the shattered flat screen as the narrator asks, “Want to get away?”

Such a scene is unlikely to have taken place in the early days of video games when Atari reigned supreme and the action of playing solely centered on hand–eye coordination. The learning curve was relatively nonexistent; players maneuvered a joystick to shoot lines of aliens in the sky, or they turned the wheel on a paddle to play a virtual game of table tennis.

But as video games became increasingly popular, they also became increasingly complex. Consoles upgraded and evolved on a regular basis, and the games kept up. Players called each other with loopholes and tips on how to get Mario and Luigi onto the next level, and now they exchange their tricks on gaming blogs. Games like The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy created alternate worlds and intricate story lines, providing multiple-hour epic adventures.

Long criticized for taking kids out of the backyard and into a sedentary spot in front of the TV, many video games have circled back to their simpler origins and, in doing so, have made players more active. Casual gamers who could quickly figure out how to put together puzzle pieces in Tetris can now just as easily figure out how to “swing” a tennis racket with a Wiimote. Video games are no longer a convenient scapegoat for America’s obesity problems; Wii Fit offers everything from yoga to boxing, and Dance Dance Revolution estimates calories burned while players dance.

The logistics of video games continue to change, and as they do, gaming has begun to intersect with every other part of culture. Players can learn how to “perform” their favorite songs with Guitar Hero and Rock Band. Product placement akin to what is seen in movies and on TV is equally prevalent in video games such as the popular Forza Motorsport or FIFA series. As the Internet allows for players across the world to participate simultaneously, video games have the potential to one day look like competitive reality shows (Dolan). Arguably, video games even hold a place in the art world, with the increasing complexity of animation and story lines (Tres Kap).

And now, with endless possibilities for the future, video games are attracting new and different demographics. Avid players who grew up with video games may be the first ones to purchase 3-D televisions for the 3-D games of the future (Williams, 2010). But casual players, perhaps of an older demographic, will be drawn to the simplicity of a game like Wii Bowling. Video games have become more accessible than ever. Social media websites like Facebook offer free video game applications, and smartphone users can download apps for as little as a dollar, literally putting video games in one’s back pocket. Who needs a cumbersome Scrabble board when it’s available on a touch screen anytime, anywhere?

Video games have become ubiquitous in modern culture. Understanding them as a medium allows a fuller understanding of their implications in the realms of entertainment, information, and communication. Studying their history reveals new perspectives on the ways video games have affected mainstream culture.

References

Dolan, Michael. “The Video Game Revolution: The Future of Video Gaming,” PBS, http://www.pbs.org/kcts/videogamerevolution/impact/future.html.

Tres Kap, Jona. “The Video Game Revolution: But is it Art?” PBS, http://www.pbs.org/kcts/videogamerevolution/impact/art.html.

Williams, M. H. “Study Shows Casual and Core Gamers Are Ready for 3-D Gaming,” Industry Gamers, June 15, 2010, http://www.industrygamers.com/news/study-shows-casual-and-core-gamers-are-ready-for-3d-gaming/.

10.2 The Evolution of Electronic Games

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major companies involved in video game production.

- Explain the important innovations that drove the acceptance of video games by mainstream culture.

- Determine major technological developments that influenced the evolution of video games.

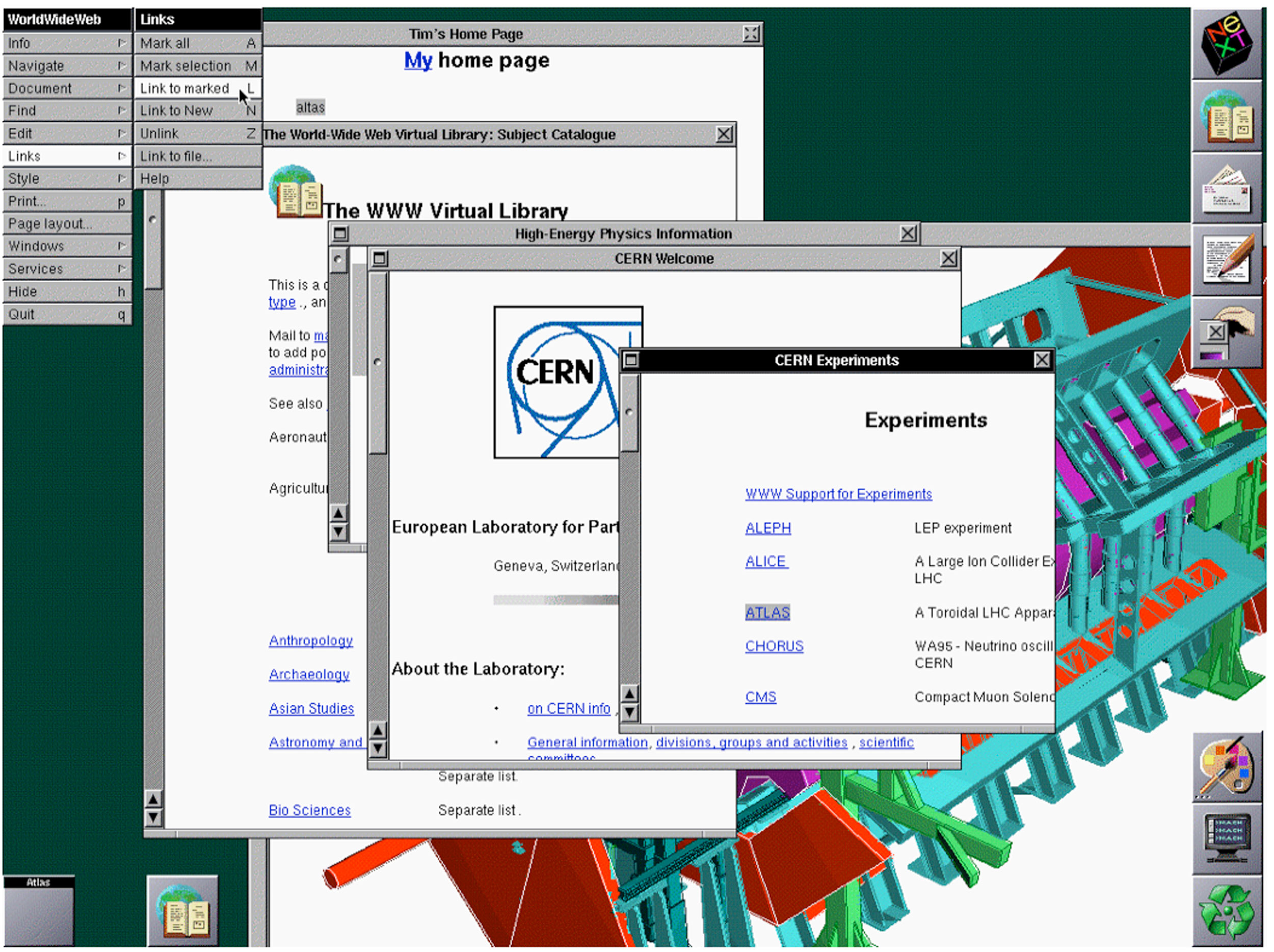

Pong, the electronic table-tennis simulation game, was the first video game for many people who grew up in the 1970s and is now a famous symbol of early video games. However, the precursors to modern video games were created as early as the 1950s. In 1952 a computer simulation of tic-tac-toe was developed for the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC), one of the first stored-information computers, and in 1958 a game called Tennis for Two was developed at Brookhaven National Laboratory as a way to entertain people coming through the laboratory on tours (Egenfeldt-Nielsen, 2008).

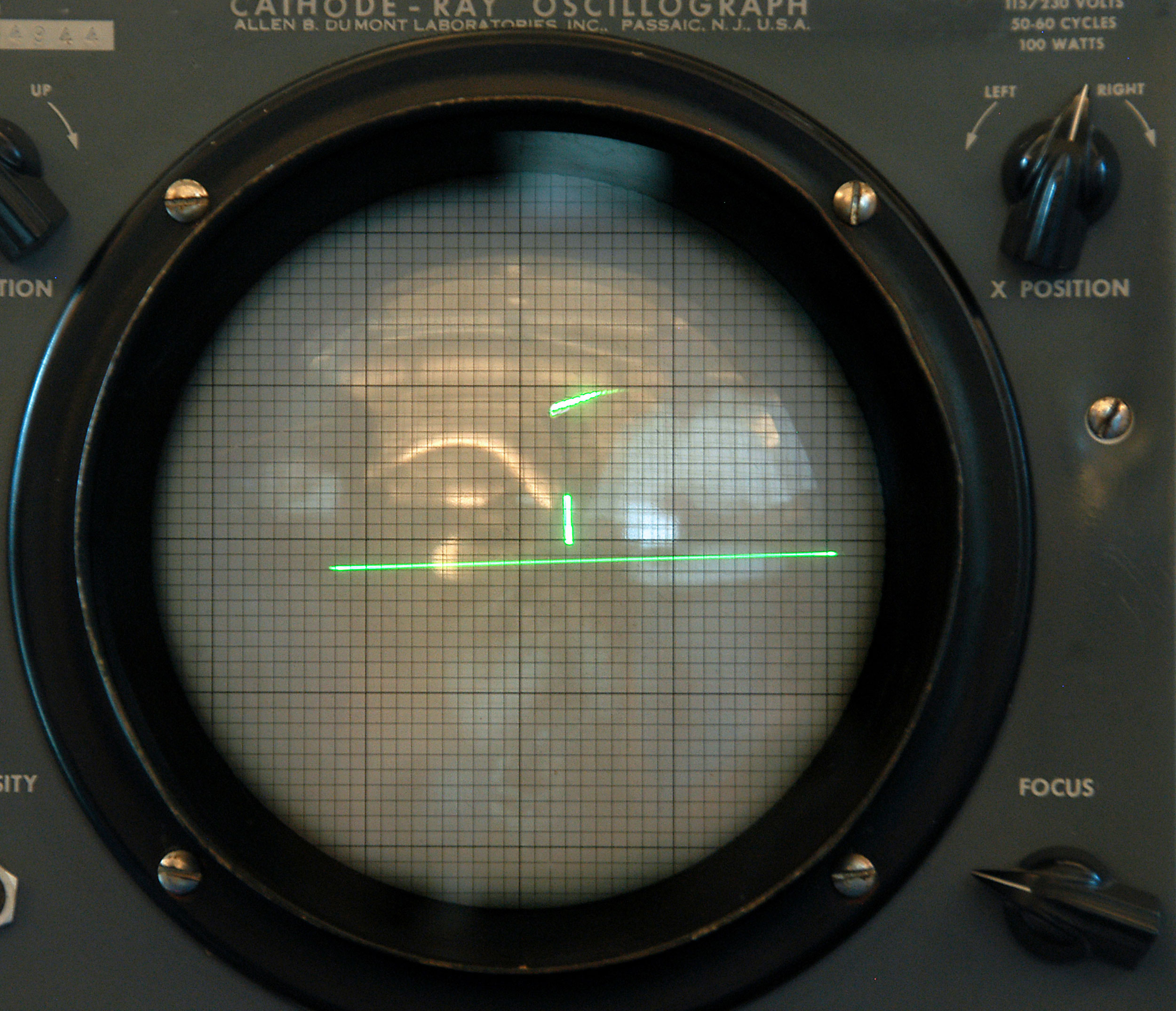

Figure 10.2

Tennis for Two was a rudimentary game designed to entertain visitors to the Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

These games would generate little interest among the modern game-playing public, but at the time they enthralled their users and introduced the basic elements of the cultural video game experience. In a time before personal computers, these games allowed the general public to access technology that had been restricted to the realm of abstract science. Tennis for Two created an interface where anyone with basic motor skills could use a complex machine. The first video games functioned early on as a form of media by essentially disseminating the experience of computer technology to those who did not have access to it.

As video games evolved, their role as a form of media grew as well. Video games have grown from simple tools that made computing technology understandable to forms of media that can communicate cultural values and human relationships.

The 1970s: The Rise of the Video Game

The 1970s saw the rise of video games as a cultural phenomenon. A 1972 article in Rolling Stone describes the early days of computer gaming:

Reliably, at any nighttime moment (i.e. non-business hours) in North America hundreds of computer technicians are effectively out of their bodies, locked in life-or-death space combat computer-projected onto cathode ray tube display screens, for hours at a time, ruining their eyes, numbing their fingers in frenzied mashing of control buttons, joyously slaying their friend and wasting their employers’ valuable computer time. Something basic is going on (Brand, 1972).

This scene was describing Spacewar!, a game developed in the 1960s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that spread to other college campuses and computing centers. In the early ’70s, very few people owned computers. Most computer users worked or studied at university, business, or government facilities. Those with access to computers were quick to utilize them for gaming purposes.

Arcade Games

The first coin-operated arcade game was modeled on Spacewar! It was called Computer Space, and it fared poorly among the general public because of its difficult controls. In 1972, Pong, the table-tennis simulator that has come to symbolize early computer games, was created by the fledgling company Atari, and it was immediately successful. Pong was initially placed in bars with pinball machines and other games of chance, but as video games grew in popularity, they were placed in any establishment that would take them. By the end of the 1970s, so many video arcades were being built that some towns passed zoning laws limiting them (Kent, 1997).

The end of the 1970s ushered in a new era—what some call the golden age of video games—with the game Space Invaders, an international phenomenon that exceeded all expectations. In Japan, the game was so popular that it caused a national coin shortage. Games like Space Invaders illustrate both the effect of arcade games and their influence on international culture. In two different countries on opposite sides of the globe, Japanese and American teenagers, although they could not speak to one another, were having the same experiences thanks to a video game.

Video Game Consoles

The first video game console for the home began selling in 1972. It was the Magnavox Odyssey, and it was based on prototypes built by Ralph Behr in the late 1960s. This system included a Pong-type game, and when the arcade version of Pong became popular, the Odyssey began to sell well. Atari, which was making arcade games at the time, decided to produce a home version of Pong and released it in 1974. Although this system could only play one game, its graphics and controls were superior to the Odyssey, and it was sold through a major department store, Sears. Because of these advantages, the Atari home version of Pong sold well, and a host of other companies began producing and selling their own versions of Pong (Herman, 2008).

A major step forward in the evolution of video games was the development of game cartridges that stored the games and could be interchanged in the console. With this technology, users were no longer limited to a set number of games, leading many video game console makers to switch their emphasis to producing games. Several groups, such as Magnavox, Coleco, and Fairchild, released versions of cartridge-type consoles, but Atari’s 2600 console had the upper hand because of the company’s work on arcade games. Atari capitalized off of its arcade successes by releasing games that were well known to a public that was frequenting arcades. The popularity of games such as Space Invaders and Pac-Man made the Atari 2600 a successful system. The late 1970s also saw the birth of companies such as Activision, which developed third-party games for the Atari 2600 (Wolf).

Home Computers

The birth of the home computer market in the 1970s paralleled the emergence of video game consoles. The first computer designed and sold for the home consumer was the Altair. It was first sold in 1975, several years after video game consoles had been selling, and it sold mainly to a hobbyist market. During this period, people such as Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, were building computers by hand and selling them to get their start-up businesses going. In 1977, three important computers—Radio Shack’s TRS-80, the Commodore PET, and the Apple II—were produced and began selling to the home market (Reimer, 2005).

The rise of personal computers allowed for the development of more complex games. Designers of games such as Mystery House, developed in 1979 for the Apple II, and Rogue, developed in 1980 and played on IBM PCs, used the processing power of early home computers to develop video games that had extended plots and story lines. In these games, players moved through landscapes composed of basic graphics, solving problems and working through an involved narrative. The development of video games for the personal computer platform expanded the ability of video games to act as media by allowing complex stories to be told and new forms of interaction to take place between players.

The 1980s: The Crash

Atari’s success in the home console market was due in large part to its ownership of already-popular arcade games and the large number of game cartridges available for the system. These strengths, however, eventually proved detrimental to the company and led to what is now known as the video game crash of 1983. Atari bet heavily on its past successes with popular arcade games by releasing Pac-Man for the Atari 2600. Pac-Man was a successful arcade game that did not translate well to the home console, leading to disappointed consumers and lower-than-expected sales. Additionally, Atari produced 10 million of the lackluster Pac-Man games on its first run, despite the fact that active consoles were only estimated at 10 million. Similar mistakes were made with a game based on the movie E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, which has gained notoriety as one of the worst games in Atari’s history. It was not received well by consumers despite the success of the movie, and Atari had again bet heavily on its success. Piles of unsold E.T. game cartridges were reportedly buried in the New Mexico desert under a veil of secrecy (Monfort & Bogost, 2009).

As retail outlets became increasingly wary of home console failures, they began stocking fewer games on shelves. This action, combined with an increasing number of companies producing games, led to overproduction and a resulting fallout in the video game market in 1983. Many smaller game developers did not have the capacity to withstand this downturn and went out of business. Although Coleco and Atari were able to make it through the crash, neither company regained its former share of the video game market. It was 1985 when the video game market picked up again.

The Rise of Nintendo

Nintendo, a Japanese card and novelty producer that had begun to produce electronic games in the 1970s, was responsible for arcade games such as Donkey Kong in the early 1980s. Its first home console, developed in 1984 for sale in Japan, tried to succeed where Atari had failed. The Nintendo system used newer, better microchips, bought in large quantities, to ensure high-quality graphics at a price consumers could afford. Keeping console prices low meant Nintendo had to rely on games for most of its profits and maintain control of game production. This was something Atari had failed to do, and it led to a glut of low-priced games that caused the crash of 1983. Nintendo got around this problem with proprietary circuits that would not allow unlicensed games to be played on the console. This allowed Nintendo to dominate the home video game market through the end of the decade, when one-third of homes in the United States had a Nintendo system (Cross & Smits, 2005).

Nintendo introduced its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in the United States in 1985. The game Super Mario Brothers, released with the system, was also a landmark in video game development. The game employed a narrative in the same manner as more complicated computer games, but its controls were accessible and its objectives simple. The game appealed to a younger demographic, generally boys in the 8–14 range, than the one targeted by Atari (Kline, et. al., 2003). Its designer, Shigeru Miyamoto, tried to mimic the experiences of childhood adventures, creating a fantasy world not based on previous models of science fiction or other literary genres (McLaughlin, 2007). Super Mario Brothers also gave Nintendo an iconic character who has been used in numerous other games, television shows, and even a movie. The development of this type of character and fantasy world became the norm for video game makers. Games such as The Legend of Zelda became franchises with film and television possibilities rather than simply one-off games.

As video games developed as a form of media, the public struggled to come to grips with the kind of messages this medium was passing on to children. These were no longer simple games of reflex that could be compared to similar nonvideo games or sports; these were forms of media that included stories and messages that concerned parents and children’s advocates. Arguments about the larger meaning of the games became common, with some seeing the games as driven by ideas of conquest and gender stereotypes, whereas others saw basic stories about traveling and exploration (Fuller & Jenkins, 1995).

Other Home Console Systems

Other software companies were still interested in the home console market in the mid-1980s. Atari released the 2600jr and the 7800 in 1986 after Nintendo’s success, but the consoles could not compete with Nintendo. The Sega Corporation, which had been involved with arcade video game production, released its Sega Master System in 1986. Although the system had more graphics possibilities than the NES, Sega failed to make a dent in Nintendo’s market share until the early 1990s, with the release of Sega Genesis (Kerr, 2005).

Computer Games Flourish and Innovate

The enormous number of games available for Atari consoles in the early 1980s took its toll on video arcades. In 1983, arcade revenues had fallen to a 3-year low, leading game makers to turn to newer technologies that could not be replicated by home consoles. This included arcade games powered by laser discs, such as Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace, but their novelty soon wore off, and laser-disc games became museum pieces (Harmetz, 1984). In 1989, museums were already putting on exhibitions of early arcade games that included ones from the early 1980s. Although newer games continued to come out on arcade platforms, they could not compete with the home console market and never achieved their previous successes from the early 1980s. Increasingly, arcade gamers chose to stay at home to play games on computers and consoles. Today, dedicated arcades are a dying breed. Most that remain, like the Dave & Buster’s and Chuck E. Cheese’s chains, offer full-service restaurants and other entertainment attractions to draw in business.

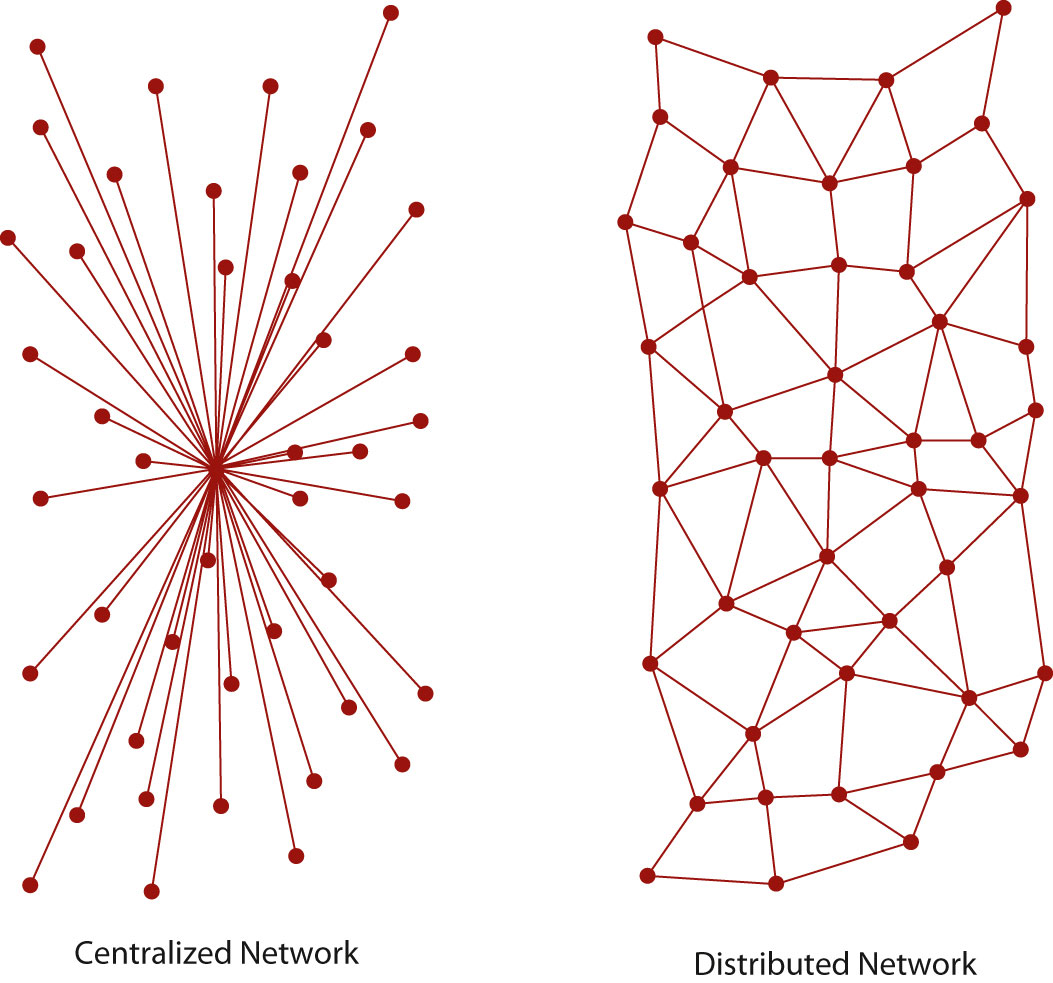

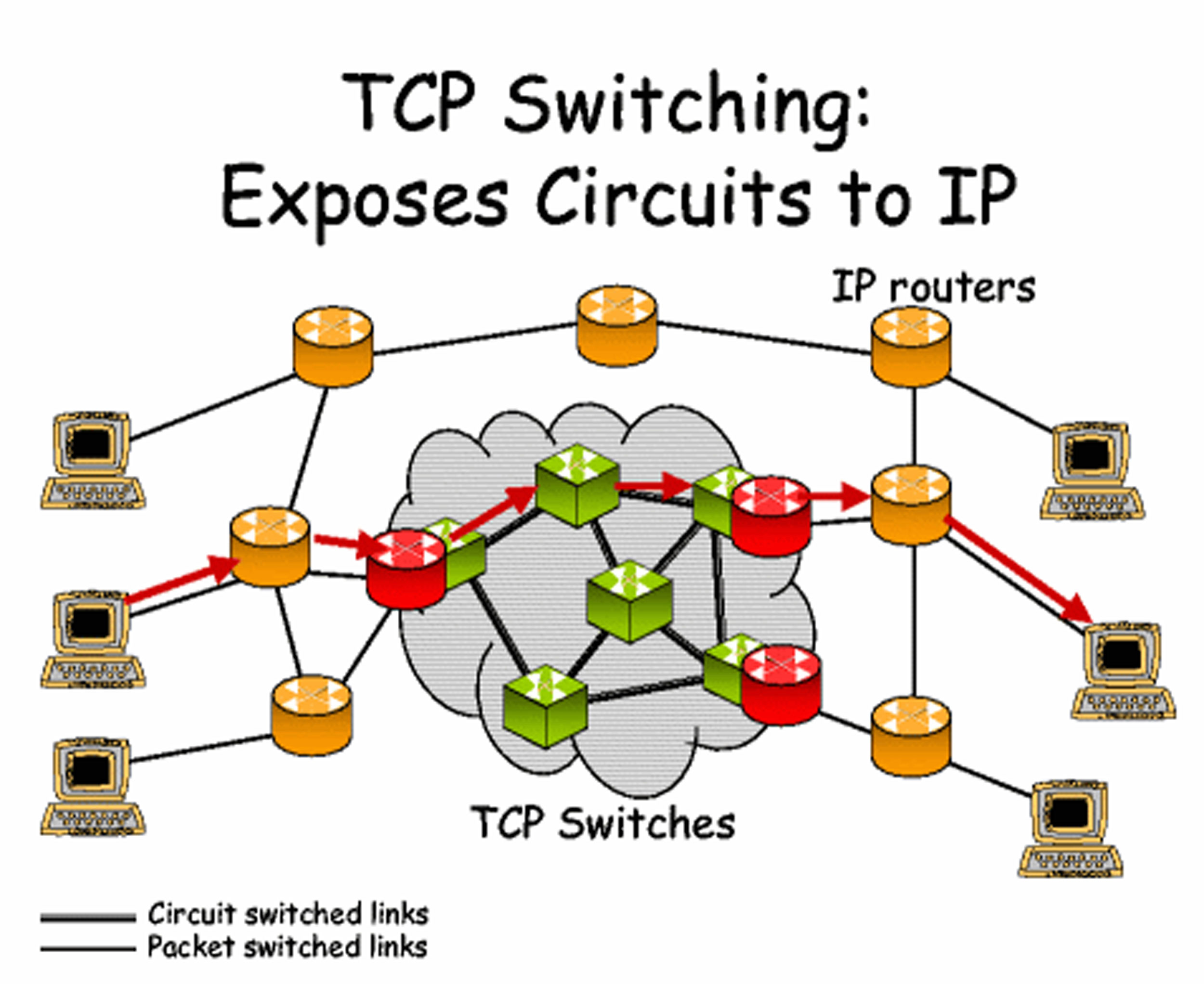

Home games fared better than arcades because they could ride the wave of personal computer purchases that occurred in the 1980s. Some important developments in video games occurred in the mid-1980s with the development of online games. Multiuser dungeons, or MUDs, were role-playing games played online by multiple users at once. The games were generally text-based, describing the world of the MUD through text rather than illustrating it through graphics. The games allowed users to create a character and move through different worlds, accomplishing goals that awarded them with new skills. If characters attained a certain level of proficiency, they could then design their own area of the world. Habitat, a game developed in 1986 for the Commodore 64, was a graphic version of this type of game. Users dialed up on modems to a central host server and then controlled characters on screen, interacting with other users (Reimer, 2005).

During the mid-1980s, a demographic shift occurred. Between 1985 and 1987, games designed to run on business computers rose from 15 percent to 40 percent of games sold (Elmer-Dewitt, et. al., 1987). This trend meant that game makers could use the increased processing power of business computers to create more complex games. It also meant adults were interested in computer games and could become a profitable market.

The 1990s: The Rapid Evolution of Video Games

Video games evolved at a rapid rate throughout the 1990s, moving from the first 16-bit systems (named for the amount of data they could process and store) in the early 1990s to the first Internet-enabled home console in 1999. As companies focused on new marketing strategies, wider audiences were targeted, and video games’ influence on culture began to be felt.

Console Wars

Nintendo’s dominance of the home console market throughout the late 1980s allowed it to build a large library of games for use on the NES. This also proved to be a weakness, however, because Nintendo was reluctant to improve or change its system for fear of making its game library obsolete. Technology had changed in the years since the introduction of the NES, and companies such as NEC and Sega were ready to challenge Nintendo with 16-bit systems (Slaven).

Figure 10.3

Sega’s commercials suggested that it was a more violent version of Nintendo.

jeriaska – Splatterhouse – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Sega Master System had failed to challenge the NES, but with the release of its 16-bit system, Sega Genesis, the company pursued a new marketing strategy. Whereas Nintendo targeted 8- to 14-year-olds, Sega’s marketing plan targeted 15- to 17-year olds, making games that were more mature and advertising during programs such as the MTV Video Music Awards. The campaign successfully branded Sega as a cooler version of Nintendo and moved mainstream video games into a more mature arena. Nintendo responded to the Sega Genesis with its own 16-bit system, the Super NES, and began creating more mature games as well. Games such as Sega’s Mortal Kombat and Nintendo’s Street Fighter competed to raise the level of violence possible in a video game. Sega’s advertisements even suggested that its game was better because of its more violent possibilities (Gamespot).

By 1994, companies such as 3DO, with its 32-bit system, and Atari, with its allegedly 64-bit Jaguar, attempted to get in on the home console market but failed to use effective marketing strategies to back up their products. Both systems fell out of production before the end of the decade. Sega, fearing that its system would become obsolete, released the 32-bit Saturn system in 1995. The system was rushed into production and did not have enough games available to ensure its success (Cyberia PC). Sony stepped in with its PlayStation console at a time when Sega’s Saturn was floundering and before Nintendo’s 64-bit system had been released. This system targeted an even older demographic of 14- to 24-year-olds and made a large effect on the market; by March of 2007, Sony had sold 102 million PlayStations (Edge Staff, 2009).

Computer Games Gain Mainstream Acceptance

Computer games had avid players, but they were still a niche market in the early 1990s. An important step in the mainstream acceptance of personal computer games was the development of the first-person shooter genre. First popularized by the 1992 game Wolfenstein 3D, these games put the player in the character’s perspective, making it seem as if the player were firing weapons and being attacked. Doom, released in 1993, and Quake, released in 1996, used the increased processing power of personal computers to create vivid three-dimensional worlds that were impossible to fully replicate on video game consoles of the era. These games pushed realism to new heights and began attracting public attention for their graphic violence.

Figure 10.4

Myst challenged the notion that only violent games could be successful.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Another trend was reaching out to audiences outside of the video-game-playing community. Myst, an adventure game where the player walked around an island solving a mystery, drove sales of CD-ROM drives for computers. Myst, its sequel Riven, and other nonviolent games such as SimCity actually outsold Doom and Quake in the 1990s (Miller, 1999). These nonviolent games appealed to people who did not generally play video games, increasing the form’s audience and expanding the types of information that video games put across.

Online Gaming Gains Popularity

A major advance in game technology came with the increase in Internet use by the general public in the 1990s. A major feature of Doom was the ability to use multiplayer gaming through the Internet. Strategy games such as Command and Conquer and Total Annihilation also included options where players could play each other over the Internet. Other fantasy-inspired role-playing games, such as Ultima Online, used the Internet to initiate the massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) genre (Reimer). These games used the Internet as their platform, much like the text-based MUDs, creating a space where individuals could play the game while socially interacting with one another.

Portable Game Systems

The development of portable game systems was another important aspect of video games during the 1990s. Handheld games had been in use since the 1970s, and a system with interchangeable cartridges had even been sold in the early 1980s. Nintendo released the Game Boy in 1989, using the same principles that made the NES dominate the handheld market throughout the 1990s. The Game Boy was released with the game Tetris, using the game’s popularity to drive purchases of the unit. The unit’s simple design meant users could get 20 hours of playing time on a set of batteries, and this basic design was left essentially unaltered for most of the decade. More advanced handheld systems, such as the Atari Lynx and Sega Game Gear, could not compete with the Game Boy despite their superior graphics and color displays (Hutsko, 2000).

The decade-long success of the Game Boy belies the conventional wisdom of the console wars that more advanced technology makes for a more popular system. The Game Boy’s static, simple design was readily accessible, and its stability allowed for a large library of games to be developed for it. Despite using technology almost a decade old, the Game Boy accounted for 30 percent of Nintendo of America’s overall revenues at the end of the 1990s (Hutsko, 2000).

The Early 2000s: 21st-Century Games

The Console Wars Continue

Sega gave its final effort in the console wars with the Sega Dreamcast in 1999. This console could connect to the Internet, emulating the sophisticated computer games of the 1990s. The new features of the Sega Dreamcast were not enough to save the brand, however, and Sega discontinued production in 2001, leaving the console market entirely (Business Week).

A major problem for Sega’s Dreamcast was Sony’s release of the PlayStation 2 (PS2) in 2000. The PS2 could function as a DVD player, expanding the role of the console into an entertainment device that did more than play video games. This console was incredibly successful, enjoying a long production run, with more than 106 million units sold worldwide by the end of the decade (A Brief History of Game Console Warfare).

In 2001, two major consoles were released to compete with the PS2: the Xbox and the Nintendo GameCube. The Xbox was an attempt by Microsoft to enter the market with a console that expanded on the functions of other game consoles. The unit had features similar to a PC, including a hard drive and an Ethernet port for online play through its service, Xbox Live. The popularity of the first-person shooter game Halo, an Xbox exclusive release, boosted sales as well. Nintendo’s GameCube did not offer DVD playback capabilities, choosing instead to focus on gaming functions. Both of these consoles sold millions of units but did not come close to the sales of the PS2.

Computer Gaming Becomes a Niche Market

As consoles developed to rival the capabilities of personal computers, game developers began to focus more on games for consoles. From 2000 to the end of the decade, the popularity of personal computer games has gradually declined. The computer gaming community, while still significant, is focused on game players who are willing to pay a lot of money on personal computers that are designed specifically for gaming, often including multiple monitors and user modifications that allow personal computers to play newer games. This type of market, though profitable, is not large enough to compete with the audience for the much cheaper game consoles (Kalning, 2008).

The Evolution of Portable Gaming

Nintendo continued its control of the handheld game market into the 2000s with the 2001 release of the Game Boy Advance, a redesigned Game Boy that offered 32-bit processing and compatibility with older Game Boy games. In 2004, anticipating Sony’s upcoming handheld console, Nintendo released the Nintendo DS, a handheld console that featured two screens and Wi-Fi capabilities for online gaming. Sony’s PlayStation Portable (PSP) was released the following year and featured Wi-Fi capabilities as well as a flexible platform that could be used to play other media such as MP3s (Patsuris, 2004). These two consoles, along with their newer versions, continue to dominate the handheld market

One interesting innovation in mobile gaming occurred in 2003 with the release of the Nokia N-Gage. The N-Gage was a combination of a game console and mobile phone that, according to consumers, did not fill either role very well. The product line was discontinued in 2005, but the idea of playing games on phones persisted and has been developed on other platforms (Stone, 2007). Apple currently dominates the industry of mobile phone games; in 2008 and 2009 alone, iPhone games generated $615 million in revenue (Farago, 2010). As mobile phone gaming grows in popularity and as the supporting technology becomes increasingly more advanced, traditional portable gaming platforms like the DS and the PSP will need to evolve to compete. Nintendo is already planning a successor to the DS that features 3-D graphics without the use of 3-D glasses that it hopes will help the company retain and grow its share of the portable gaming market.

Video Games Today

The trends of the late 2000s have shown a steadily increasing market for video games. Newer control systems and family-oriented games have made it common for many families to engage in video game play as a group. Online games have continued to develop, gaining unprecedented numbers of players. The overall effect of these innovations has been the increasing acceptance of video game culture by the mainstream.

Home Consoles

The current state of the home console market still involves the three major companies of the past 10 years: Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft. The release of Microsoft’s Xbox 360 led this generation of consoles in 2005. The Xbox 360 featured expanded media capabilities and integrated access to Xbox Live, an online gaming service. Sony’s PlayStation 3 (PS3) was released in 2006. It also featured enhanced online access as well as expanded multimedia functions, with the additional capacity to play Blu-ray discs. Nintendo released the Wii at the same time. This console featured a motion-sensitive controller that departed from previous controllers and focused on accessible, often family-oriented games. This combination successfully brought in large numbers of new game players, including many older adults. By June 2010, in the United States, the Wii had sold 71.9 million units, the Xbox 360 had sold 40.3 million, and the PS3 trailed at 35.4 million (VGChartz, 2010). In the wake of the Wii’s success, Microsoft and Sony have introduced their own motion-sensitive systems (Mangalindan, 2010).

Key Takeaways

- In a time before personal computers, early video games allowed the general public to access technology that had been restricted to the realm of abstract science. Tennis for Two created an interface where anyone with basic motor skills could use a complex machine. The first video games functioned early on as a form of media by essentially disseminating the experience of computer technology to those without access to it.

- Video games reached wider audiences in the 1990s with the advent of the first-person shooter genre and popular nonaction games such as Myst. The games were marketed to older audiences, and their success increased demand for similar games.

- Online capabilities that developed in the 1990s and expanded in the 2000s allowed players to compete in teams. This innovation attracted larger audiences to gaming and led to new means of social communication.

- A new generation of accessible, family-oriented games in the late 2000s encouraged families to interact through video games. These games also brought in older demographics that had never used video games before.

Exercises

Video game marketing has changed to bring in more and more people to the video game audience. Think about the influence video games have had on you or people you know. If you have never played video games, then think about the ways your conceptions of video games have changed. Sketch out a timeline indicating the different occurrences that marked your experiences related to video games. Now compare this timeline to the history of video games from this section. Consider the following questions:

- How did your own experiences line up with the history of video games?

- Did you feel the effects of marketing campaigns directed at you or those around you?

- Were you introduced to video games during a surge in popularity? What games appealed to you?

References

A Brief History of Game Console Warfare, “PlayStation 2,” slide in “A Brief History of Game Console Warfare.”

Brand, Stewart. “Space War,” Rolling Stone, December 7, 1972.

Business Week, “Sega Dreamcast,” slide in “A Brief History of Game Console Warfare,” Business Week, http://images.businessweek.com/ss/06/10/game_consoles/.

Cross, Gary and Gregory Smits, “Japan, the U.S. and the Globalization of Children’s Consumer Culture,” Journal of Social History 38, no. 4 (2005).

CyberiaPC.com, “Sega Saturn (History, Specs, Pictures),” http://www.cyberiapc.com/vgg/sega_saturn.htm.

Edge staff, “The Making Of: Playstation,” Edge, April 24, 2009, http://www.next-gen.biz/features/the-making-of-playstation.

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon. Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2008), 50.

Elmer-Dewitt, Philip and others, “Computers: Games that Grownups Play,” Time, July 27, 1987, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,965090,00.html.

Farago, Peter. “Apple iPhone and iPod Touch Capture U.S. Video Game Market Share,” Flurry (blog), March 22, 2010, http://blog.flurry.com/bid/31566/Apple-iPhone-and-iPod-touch-Capture-U-S-Video-Game-Market-Share.

Fuller, Mary and Henry Jenkins, “Nintendo and New World Travel Writing: A Dialogue,” Cybersociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, ed. Steven G. Jones (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995), 57–72.

Gamespot, “When Two Tribes Go to War: A History of Video Game Controversy,” http://www.gamespot.com/features/6090892/p-5.html.

Harmetz, Aljean. “Video Arcades Turn to Laser Technology as Queues Dwindle,” Morning Herald (Sydney), February 2, 1984.

Herman, Leonard. “Early Home Video Game Systems,” in The Video Game Explosion: From Pong to PlayStation and Beyond, ed. Mark Wolf (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2008), 54.

Hutsko, Joe. “88 Million and Counting; Nintendo Remains King of the Handheld Game Players,” New York Times, March 25, 2000, http://www.nytimes.com/2000/03/25/business/88-million-and-counting-nintendo-remains-king-of-the-handheld-game-players.html.

Kalning, Kristin. “Is PC Gaming Dying? Or Thriving?” MSNBC, March 26, 2008, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23800152/wid/11915773/.

Kent, “Super Mario Nation.”

Kent, Steven. “Super Mario Nation,” American Heritage, September 1997, http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1997/5/1997_5_65.shtml.

Kerr, Aphra. “Spilling Hot Coffee? Grand Theft Auto as Contested Cultural Product,” in The Meaning and Culture of Grand Theft Auto: Critical Essays, ed. Nate Garrelts (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005), 17.

Kline, Stephen, Nick Dyer-Witheford, and Greig De Peuter, Digital Play: The Interaction of Technology, Culture, and Marketing (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 119.

Mangalindan, J. P. “Is Casual Gaming Destroying the Traditional Gaming Market?” Fortune, March 18, 2010, http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2010/03/18/is-casual-gaming-destroying-the-traditional-gaming-market/.

McLaughlin, Rus. “IGN Presents the History of Super Mario Bros.,” IGN Retro, November 8, 2007, http://games.ign.com/articles/833/833615p1.html.

Miller, Stephen C. “News Watch; Most-Violent Video Games Are Not Biggest Sellers,” New York Times, July 29, 1999, http://www.nytimes.com/1999/07/29/technology/news-watch-most-violent-video-games-are-not-biggest-sellers.html.

Montfort, Nick and Ian Bogost, Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), 127.

Patsuris, Penelope. “Sony PSP vs. Nintendo DS,” Forbes, June 7, 2004, http://www.forbes.com/2004/06/07/cx_pp_0607mondaymatchup.html.

Reimer, “The Evolution of Gaming.”

Reimer, Jeremy. “The Evolution of Gaming: Computers, Consoles, and Arcade,” Ars Technica (blog), October 10, 2005, http://arstechnica.com/old/content/2005/10/gaming-evolution.ars/4.

Reimer, Jeremy. “Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures,” Ars Technica (blog), December 14, 2005, http://arstechnica.com/old/content/2005/12/total-share.ars/2.

Slaven, Andy. Video Game Bible, 1985–2002, (Victoria, BC: Trafford), 70–71.

Stone, Brad. “Play It Again, Nokia. For the Third Time,” New York Times, August 27, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/27/technology/27nokia.html.

VGChartz, “Weekly Hardware Chart: 19th June 2010,” http://www.vgchartz.com.

Wolf, Mark J. P. “Arcade Games of the 1970s,” in The Video Game Explosion (see note 7), 41.

10.3 Influential Contemporary Games

Learning Objectives

- Identify the effect electronic games have on culture.

- Select the most influential and important games released to the general public within the last few years.

- Describe ways new games have changed the video game as a form of media.

With such a short history, the place of video games in culture is constantly changing and being redefined. Are video games entertainment or art? Should they focus on fostering real-life skills or developing virtual realities? Certain games have come to prominence in recent years for their innovations and genre-expanding attributes. These games are notable for not only great economic success and popularity but also for having a visible influence on culture.

Guitar Hero and Rock Band

The musical series Guitar Hero, based on a Japanese arcade game of the late ’90s, was first launched in North America in 2005. In the game, the player uses a guitar-shaped controller to match the rhythms and notes of famous rock songs. The closer the player approximates the song, the better the score. This game introduced a new genre of games in which players simulate playing musical instruments. Rock Band, released in 2007, uses a similar format, including a microphone for singing, a drum set, and rhythm and bass guitars. These games are based on a similar premise as earlier rhythm-based games such as Dance Dance Revolution, in which players keep the rhythm on a dance pad. Dance Dance Revolution, which was introduced to North American audiences in 1999, was successful but not to the extent that the later band-oriented games were. In 2008, music-based games brought in an estimated $1.9 billion.

Figure 10.5

Rock Band includes a microphone and a drum set along with a guitar.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain; Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0; Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

GAME Online – World of Warcraft: Cataclysm for PC – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Guitar Hero and Rock Band brought new means of marketing and a kind of cross-media stimulus with them. The songs featured in the games experienced increased downloads and sales—as much as an 840 percent increase in some cases (Peckham, 2008). The potential of this type of game did not escape its developers or the music industry. Games dedicated solely to one band were developed, such as Guitar Hero: Aerosmith and The Beatles: Rock Band. These games were a mix of music documentary, greatest hits album, and game. They included footage from early concerts, interviews with band members, and, of course, songs that allowed users to play along. When Guitar Hero: Aerosmith was released, the band’s catalog experienced a 40 percent increase in sales (Quan, 2008).

The rock band Metallica made its album Death Magnetic available for Guitar Hero III on the same day it was released as an album (Quan, 2008). Other innovations include Rock Band Network, a means for bands and individuals to create versions of their own songs for Rock Band that can be downloaded for a fee. The sporadic history of the video game industry makes it unclear if this type of game will maintain market share or even maintain its popularity, but it has clearly opened new avenues of expression as a form of media.

The Grand Theft Auto series

The first game in the Grand Theft Auto (GTA) series was released in 1997 for the PC and Sony PlayStation. The game had players stealing cars—not surprising given its title—and committing a variety of crimes to achieve specific goals. The game’s extreme violence made it popular with players of the late 1990s, but its true draw was the variety of options that players could employ in the game. Specific narratives and goals could be pursued, but if players wanted to drive around and explore the city, they could do that as well. A large variety of cars, from sports cars to tractor trailers, were available depending on the player’s goals. The violence could likewise be taken to any extreme the player wished, including stealing cars, killing pedestrians, and engaging the police in a shoot-out. This type of game is known as a sandbox game, or open world, and it is defined by the ability of users to freely pursue their own objectives (Donald, 2000).

The GTA series has evolved over the past decade by increasing the realism, options, and explicit content of the first game. GTA III and GTA IV, as well as a number of spin-off games, such as the recent addition The Ballad of Gay Tony, have made the franchise more profitable and more controversial. These newer games have expanded on the idea of an open video game world, allowing players to have their characters buy and manage businesses, play unrelated mini-games (such as bowling and darts), and listen to a wide variety of in-game music, talk shows, and even television programs. However, increasing freedom also results in increasing controversy, as players can choose to solicit prostitutes, visit strip clubs, perform murder sprees, and assault law enforcement agents. Lawsuits have attempted to tie the games to real-life instances of violence, and GTA games are routinely the target of political investigations into video game violence (Morales, 2005).

World of Warcraft

World of Warcraft (WoW), released in 2004, is a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) loosely based on the Warcraft strategy franchise of the 1990s. The game is conducted entirely online, though it is accessed through purchased software, and players purchase playing time. Each player chooses an avatar, or character, that belongs to one of several races, such as orcs, elves, and humans. These characters can spend their time on the game by completing quests, learning trades, or simply interacting with other characters. As characters gain experience, they obtain skills and earn virtual money. Players also choose whether they can attack other players without prior agreement by choosing a PvP (player versus player) server. The normal server allows players to fight each other, but it can only be done if both players consent. A third server is reserved for those players who want to role-play, or act in character.

Figure 10.6

World of Warcraft allows players to team up with other avatars to go on quests or just socialize.

GAME Online – World of Warcraft: Cataclysm for PC – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Various organizations have sprung up within the WoW universe. Guilds are groups that ascribe to specific codes of conduct and work together to complete tasks that cannot be accomplished by a lone individual. The guilds are organized by the players; they are not maintained by WoW developers. Each has its own unique identity and social rules, much like a college fraternity or social club. Voice communication technology allows players to speak to each other as they complete missions and increases the social bonding that holds such organizations together (Barker, 2006).

WoW has taken the medium of video games to unprecedented levels. Although series such as Grand Theft Auto allow players a great deal of freedom, everything done in the games was accounted for at some point. WoW, which depends on the actions of millions of players to drive the game, allows people to literally live their lives through a game. In the game, players can earn virtual gold by mining it, killing enemies, and killing other players. It takes a great deal of time to accumulate gold in this manner, so many wealthy players choose to buy this gold with actual dollars. This is technically against the rules of the game, but these rules are unenforceable. Entire real-world industries have developed from this trade in gold. Chinese companies employ workers, or “gold farmers,” who work 10-hour shifts finding gold in WoW so that the company can sell it to clients. Other players make money by finding deals on virtual goods and then selling them for a profit. One WoW player even “traveled” to Asian servers to take advantage of cheap prices, conducting a virtual import–export business (Davis, 2009).

The unlimited possibilities in such a game expand the idea of what a game is. It is obvious that an individual who buys a video game, takes it home, and plays it during his or her leisure is, in fact, playing a game. But if that person is a “gold farmer” doing repetitious tasks in a virtual world to make a real-world living, the situation is not as clear. WoW challenges conventional notions of what a game is by allowing the players to create their own goals. To some players, the goal may be to gain a high level for their character; others may be interested in role-playing, whereas others are focused on making a profit. This kind of flexibility leads to the development of scenarios never before encountered in game-play, such as the development of economic classes.

Call of Duty: Modern Warfare

The Call of Duty series of first-person shooter games is notable for its record-breaking success in the video game market, generating more than $3 billion in retail sales through late 2009 (Ivan, 2009). Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 was released in 2009 to critical acclaim and a great deal of controversy. The game included a 5-minute sequence in which the player, as a CIA agent infiltrating a terrorist cell, takes part in a massacre of innocent civilians. The player was not required to shoot civilians and could skip the sequence if desired, but these options did not stop international attention and calls to ban the game (Games Radar, 2009). Proponents of the series argue that Call of Duty has a Mature rating and is not meant to be played by minors. They also point out that the games are less violent than many modern movies. However, the debate has continued, escalating as far as the United Kingdom’s House of Commons (Games Radar, 2009).

Wii Sports and Wii Fit

The Nintendo Wii, with its dedicated motion-sensitive controller, was sold starting in 2006. The company had attempted to implement similar controllers in the past, including the Power Glove in 1989, but it had never based an entire console around such a device. The Wii’s simple design was combined with basic games such as Wii Sports to appeal to previously untapped audiences. Wii Sports was included with purchase of the Wii console and served as a means to demonstrate the new technology. It included five games: baseball, bowling, boxing, tennis, and golf. Wii Sports created a way for group play without the need for familiarity with video games. It was closer to outdoor social games such as horseshoes or croquet than it was to Doom. There was also nothing objectionable about it: no violence, no in-your-face intensity—just a game that even older people could access and enjoy. Wii Bowling tournaments were sometimes organized by retirement communities, and many people found the game to be a new way to socialize with their friends and families (Wischnowsky, 2007).

Wii Fit combined the previously incompatible terms “fitness” and “video games.” Using a touch-sensitive platform, players could do aerobics, strength training, and yoga. The game kept track of players’ weights, acting as a kind of virtual trainer (Vella, 2008).Wii Fit used the potential of video games to create an interactive version of an exercise machine, replacing workout videos and other forms of fitness that had never before considered Nintendo a competitor. This kind of design used the inherent strengths of video games to create a new kind of experience.

Nintendo found most of its past success marketing to younger demographics with games that were less controversial than the 1990s first-person shooters. Wii Sports and Wii Fit saw Nintendo playing to its strengths and expanding on them with family-friendly games that encouraged multiple generations to use video games as a social platform. This campaign was so successful that it is being imitated by rival companies Sony and Microsoft, which have released the Sony PlayStation Move and the Microsoft Kinect.

Key Takeaways

- Guitar Hero and Rock Band created a new means of marketing for the music industry. Music featured on the games experienced increased downloads and sales.

- The Grand Theft Auto series was revolutionary and controversial for its open-ended field. Players could choose from a number of different options, allowing them to set their own goals and create their own version of the game.

- World of Warcraft has brought the MMORPG genre to new heights of popularity. The large number of users has made the game evolve to a level of complexity unheard of in video games.

- Wii Sports and Wii Fit brought video games to audiences that had never been tapped by game makers. Older adults and families used Wii Sports as a means of family bonding, and Wii Fit took advantage of motion-controlled game playing to enter the fitness market.

Exercises

Think about the ways in which the games from this section were innovative and groundbreaking. Consider the following questions:

- What new social, technological, or cultural areas did they explore?

- Pick one of these areas—social, technological, or cultural—and write down ways in which video games could have a future influence in this area.

References

Barker, Carson. “Team Players: Guilds Take the Lonesome Gamer Out of Seclusion…Kind Of,” Austin Chronicle, July 28, 2006, http://www.austinchronicle.com/gyrobase/Issue/story?oid=oid%3A390551.

Davis, Rowenna. “Welcome to the New Gold Mines,” Guardian (London), March 5, 2009, http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2009/mar/05/virtual-world-china?intcmp=239.

Donald, Ryan. review of Grand Theft Auto (PlayStation), CNET, 28 April 2000, http://reviews.cnet.com/legacy-game-platforms/grand-theft-auto-playstation/4505-9882_7-30971409-2.html.

Games Radar, “The Decade in Gaming: The 10 Most Shocking Moments of the Decade,” December 29, 2009, http://www.gamesradar.com/f/the-10-most-shocking-game-moments-of-the-decade/a-20091221122845427051/p-2.

Ivan, Tom. “Call of Duty Series Tops 55 Million Sales,” Edge, November 27, 2009, http://www.edge-online.com/news/call-of-duty-series-tops-55-million-sales.

Morales, Tatiana. “Grand Theft Auto Under Fire,” CBS News, July 14, 2005, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/07/13/earlyshow/living/parenting/main708794.shtml.

Peckham, Matt. Music Sales Rejuvenated by Rock Band, Guitar Hero,” PC World, December 22, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/12/22/AR2008122200798.html.

Quan, Denise. “Is ‘Guitar Hero’ Saving Rock ’n’ Roll?” CNN, August 28, 2008, http://www.cnn.com/2008/SHOWBIZ/Music/08/20/videol.games.music/.

Vella, Matt. “Wii Fit Puts the Fun in Fitness,” Business Week, May 21, 2008, http://www.businessweek.com/innovate/content/may2008/id20080520_180427.htm.

Wischnowsky, Dave. “Wii Bowling Knocks Over Retirement Home,” Chicago Tribune, February 16, 2007, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/chi-070216nintendo,0,2755896.story.

10.4 The Impact of Video Games on Culture

Learning Objectives

- Describe gaming culture and how it has influenced mainstream culture.

- Analyze the ways video games have affected other forms of media.

- Describe how video games can be used for educational purposes.

- Identify the arguments for and against the depiction of video games as an art.

An NPD poll conducted in 2007 found that 72 percent of the U.S. population had played a video game that year (Faylor, 2008). The increasing number of people playing video games means that video games are having an undeniable effect on culture. This effect is clearly visible in the increasing mainstream acceptance of aspects of gaming culture. Video games have also changed the way that many other forms of media, from music to film, are produced and consumed. Education has also been changed by video games through the use of new technologies that help teachers and students communicate in new ways through educational games such as Brain Age. As video games have an increasing influence on our culture, many have voiced their opinions on whether this form of media should be considered an art.

Game Culture

To fully understand the effects of video games on mainstream culture, it is important to understand the development of gaming culture, or the culture surrounding video games. Video games, like books or movies, have avid users who have made this form of media central to their lives. In the early 1970s, programmers got together in groups to play Spacewar!, spending a great deal of time competing in a game that was rudimentary compared to modern games (Brand). As video arcades and home video game consoles gained in popularity, youth culture quickly adapted to this type of media, engaging in competitions to gain high scores and spending hours at the arcade or with the home console.

In the 1980s, an increasing number of kids were spending time on consoles playing games and, more importantly, increasingly identifying with the characters and products associated with the games. Saturday morning cartoons were made out of the Pac-Man and Super Mario Bros. games, and an array of nongame merchandise was sold with video game logos and characters. The public recognition of some of these characters has made them into cultural icons. A poll taken in 2007 found that more Canadians surveyed could identify a photo of Mario, from Super Mario Bros., than a photo of the current Canadian prime minister (Cohn & Toronto, 2007).

As the kids who first played Super Mario Bros. began to outgrow video games, companies such as Sega, and later Sony and Microsoft, began making games to appeal to older demographics. This has increased the average age of video game players, which was 35 in 2009 (Entertainment Software Association, 2009). The Nintendo Wii has even found a new demographic in retirement communities, where Wii Bowling has become a popular form of entertainment for the residents (Wischnowsky). The gradual increase in gaming age has led to an acceptance of video games as an acceptable form of mainstream entertainment.

The Subculture of Geeks

The acceptance of video games in mainstream culture has consequently changed the way that the culture views certain people. “Geek” was the name given to people who were adept at technology but lacking in the skills that tended to make one popular, like fashion sense or athletic ability. Many of these people, because they often did not fare well in society, favored imaginary worlds such as those found in the fantasy and science fiction genres. Video games were appealing because they were both a fantasy world and a means to excel at something. Jim Rossignol, in his 2008 book This Gaming Life: Travels in Three Cities, explained part of the lure of playing Quake III online:

Cold mornings, adolescent disinterest, and a nagging hip injury had meant that I was banished from the sports field for many years. I wasn’t going to be able to indulge in the camaraderie that sports teams felt or in the extended buzz of victory through dedication and cooperation. That entire swathe of experience had been cut off from me by cruel circumstance and a good dose of self-defeating apathy. Now, however, there was a possibility for some kind of redemption: a sport for the quick-fingered and the computer-bound; a space of possibility in which I could mold friends and strangers into a proficient gaming team (Rossignol, 2008).

Video games gave a group of excluded people a way to gain proficiency in the social realm. As video games became more of a mainstream phenomenon and video game skills began to be desired by a large number of people, the popular idea of geeks changed. It is now common to see the term “geek” used to mean a person who understands computers and technology. This former slur is also prominent in the media, with headlines in 2010 such as “Geeks in Vogue: Top Ten Cinematic Nerds (Sharp, 2010).”

Many media stories focusing on geeks examine the ways in which this subculture has been accepted by the mainstream. Geeks may have become “cooler,” but mainstream culture has also become “geekier.” The acceptance of geek culture has led to acceptance of geek aesthetics. The mainstreaming of video games has led to acceptance of fantasy or virtual worlds. This is evident in the popularity of film/book series such as The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter. Comic book characters, emblems of geek culture, have become the vehicles for blockbuster movies such as Spider-Man and The Dark Knight. The idea of a fantasy or virtual world has come to appeal to greater numbers of people. Virtual worlds such as those represented in the Grand Theft Auto and Halo series and online games such as World of Warcraft have expanded the idea of virtual worlds so that they are not mere means of escape but new ways to interact (Konzack, 2006).

The Effects of Video Games on Other Types of Media

Video games during the 1970s and ’80s were often derivatives of other forms of media. E.T., Star Wars, and a number of other games took their cues from movies, television shows, and books. This began to change in the 1980s with the development of cartoons based on video games, and in the 1990s and 2000s with live-action feature films based on video games.

Television

Television programs based on video games were an early phenomenon. Pac-Man, Pole Position, and Q*bert were among the animated programs that aired in the early 1980s. In the later 1980s, shows such as The Super Mario Bros. Super Show! and The Legend of Zelda promoted Nintendo games. In the 1990s, Pokémon, originally a game developed for the Nintendo Game Boy, was turned into a television series, a card game, several movies, and even a musical (Internet Movie Database). Recently, several programs have been developed that revolve entirely around video games—the web series The Guild, for instance, tells the story of a group of friends who interact through an unspecified MMORPG.

Nielsen, the company that tabulates television ratings, has begun rating video games in a similar fashion. In 2010, this information showed that video games, as a whole, could be considered a kind of fifth network, along with the television networks NBC, ABC, CBS, and Fox (Shields, 2009). Advertisers use Nielsen ratings to decide which programs to support. The use of this system is changing public perceptions to include video game playing as a habit similar to television watching.

Video games have also influenced the way that television is produced. The Rocket Racing League, scheduled to be launched in 2011, will feature a “virtual racetrack.” Racing jets will travel along a virtual track that can only be seen by pilots and spectators with enabled equipment. Applications for mobile devices are being developed that will allow spectators to race virtual jets alongside the ones flying in real time (Hadhazy, 2010). This type of innovation is only possible with a public that has come to demand and rely on the kind of interactivity that video games provide.

Film

The rise in film adaptations of video games accompanies the increased age of video game users. In 1995, Mortal Kombat, a live-action movie based on the video game, grossed over $70 million at the box office, placing it 22nd in the rankings for that year (Box Office Mojo). Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, released in 2001, starred well-known actress Angelina Jolie and ranked No. 1 at the box office when it was released, and 15th overall for the year (Box Office Mojo). Films based on video games are an increasingly common sight at the box office, such as producer Jerry Bruckheimer’s Prince of Persia, or the recent sequel to Tron, based on the idea of a virtual gaming arena.

Another aspect of video games’ influence on films is how video game releases are marketed and perceived. The release date for anticipated game Grand Theft Auto IV was announced and marketed to compete with the release of the film Iron Man. Grand Theft Auto IV supposedly beat Iron Man by $300 million in sales. This kind of comparison is, in some ways, misleading. Video games cost much more than a ticket to a movie, so higher sales does not mean that more people bought the game than the movie. Also, the distribution apparatus for the two media is totally different. Movies can only be released in theaters, whereas video games can be sold at any retail outlet (Associated Press, 2008). What this kind of news story proves, however, is that the general public considers video games as something akin to a film. It is also important to realize that the scale of production and profit for video games is similar to that of films. Video games include music scores, actors, and directors in addition to the game designers, and the budgets for major games reflect this. Grand Theft Auto IV cost an estimated $100 million to produce (Bowditch, 2008).

Music

Video games have been accompanied by music ever since the days of the arcade. Video game music was originally limited to computer beeps turned into theme songs. The design of the Nintendo 64, Sega Saturn, and Sony PlayStation made it possible to use sampled audio on new games, meaning songs played on physical instruments could be recorded and used on video games. Beginning with the music of the Final Fantasy series, scored by famed composer Nobuo Uematsu, video game music took on film score quality, complete with full orchestral and vocal tracks. This innovation proved beneficial to the music industry. Well-known musicians such as Trent Reznor, Thomas Dolby, Steve Vai, and Joe Satriani were able to create the soundtracks for popular games, giving these artists exposure to new generations of potential fans (Video Games Music Big Hit, 1997). Composing music for video games has turned into a profitable means of employment for many musicians. Schools such as Berklee College of Music, Yale, and New York University have programs that focus on composing music for video games. The students are taught many of the same principles that are involved in film scoring (Khan, 2010).

Many rock bands have allowed their previously recorded songs to be used in video games, similar to a hit song being used on a movie soundtrack. The bands are paid for the rights to use the song, and their music is exposed to an audience that otherwise might not hear it. As mentioned earlier, games like Rock Band and Guitar Hero have been used to promote bands. The release of The Beatles: Rock Band was timed to coincide with the release of digitally remastered reissues of the Beatles’ albums.

Another phenomenon relating to music and video games involves musicians covering video game music. A number of bands perform only video game covers in a variety of styles, such as the popular Japanese group the Black Mages, which performs rock versions of Final Fantasy music. Playing video game themes is not limited to rock bands, however. An orchestra and chorus called Video Games Live started a tour in 2005 dedicated to playing well-known video game music. Their performances are often accompanied by graphics projected onto a screen showing relevant sequences from the video games (Play Symphony).

Machinima

Recently, the connection between video games and other media has increased with the popularity of machinima, animated films and series created by recording character actions inside video games. Beginning with the short film “Diary of a Camper,” filmed inside the game Quake in 1996, fans of video games have adopted the technique of machinima to tell their own stories. Although these early movies were released only online and targeted a select niche of gamers, professional filmmakers have since adopted the process, using machinima to storyboard scenes and to add a sense of individuality to computer-generated shots. This new form of media is increasingly becoming mainstream, as TV shows such as South Park and channels such as MTV2 have introduced machinima to a larger audience (Strickland).

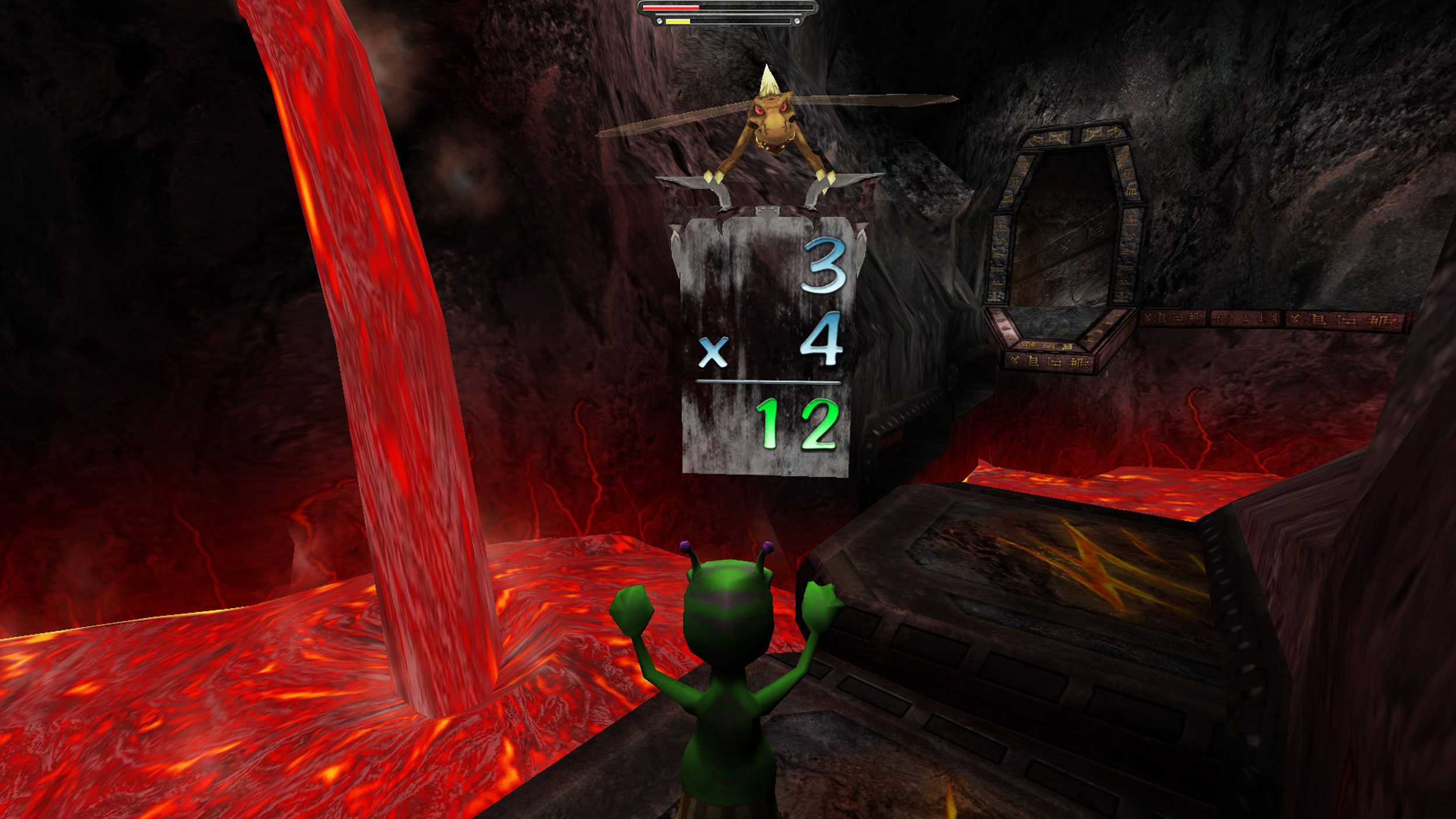

Video Games and Education

One sign of the mainstreaming of video games is the increase of educational institutions that embrace them. As early as the 1980s, games such as Number Munchers and Word Munchers were designed to help children develop basic math and grammar skills. In 2006, the Federation of American Scientists completed a study that approved of video game use in education. The study cited the fact that video game systems were present in most households, kids favored learning through video games, and games could be used to facilitate analytical skills (Feller, 2006). Another study, published in the science journal Nature in 2002, found that regular video game players had better developed visual-processing skills than people who did not play video games. Participants in the test were asked to play a first-person shooter game for 1 hour a day for 10 days, and were then tested for specific visual attention skills. The playing improved these skills in all participants, but the regular video game players had a greater skill level than the non–game players. According to the study, “Although video-game playing may seem to be rather mindless, it is capable of radically altering visual attention processing (Green & Bavelier, 2003).”

Other educational institutions have begun to embrace video games as well. The Boy Scouts of America have created a “belt loop,” something akin to a merit badge, for tasks including learning to play a parent-approved game and developing a schedule to balance video game time with homework (Murphy, 2010). The federal government has also seen the educational potential of video games. A commission on balancing the federal budget suggested a video game that would educate Americans about the necessary costs of balancing the federal budget (Wolf, 2010). The military has similarly embraced video games as training simulators for new soldiers. These simulators, working off of newer game technologies, present several different realistic options that soldiers could face on the field. The games have also been used as recruiting tools by the U.S. Army and the Army National Guard (Associated Press, 2003).

The ultimate effect of video game use for education, whether in schools or in the public arena, means that video games have been validated by established cultural authorities. Many individuals still resist the idea that video games can be beneficial or have a positive cultural influence, but their embrace by educational institutions has given video games validation.

Video Games as Art

While universally accepted as a form of media, a debate has recently arisen over whether video games can be considered a form of art. Roger Ebert, the well-known film critic, has historically argued that “video games can never be art,” citing the fact that video games are meant to be won, whereas art is meant to be experienced (Ebert, 2010).

His remarks have generated an outcry from both video gamers and developers. Many point to games such as 2009’s Flower, in which players control the flow of flower petals in the wind, as examples of video games developing into art. Flower avoids specific plot and characters to allow the player to focus on interaction with the landscape and the emotion of the game-play (That Game Company). Likewise, more mainstream games such as the popular Katamari series, released in 2004, are built around the idea of creation, requiring players to pull together a massive clump of objects in order to create a star.

Video games, once viewed as a mindless source of entertainment, are now being featured in publications such as The New Yorker magazine and The New York Times (Fisher, 2010). With the development of increasingly complex musical scores and the advent of machinima, the boundaries between video games and other forms of media are slowly blurring. While they may not be considered art by everyone, video games have contributed significantly to modern artistic culture.

Key Takeaways

- The aesthetics and principles of gaming culture have had an increasing effect on mainstream culture. This has led to the gradual acceptance of marginalized social groups and increased comfort with virtual worlds and the pursuit of new means of interaction.

- Video games have gone from being a derivative medium that took its cues from other media, such as books, films, and music, to being a form of media that other types derive new ideas from. Video games have also interacted with older forms of media to change them and create new means of entertainment and interaction.

- Educational institutions have embraced the use of video games as valuable tools for teaching. These tools include simulated worlds in which important life skills can be learned and improved.

- While video games may not be accepted by everyone as a form of art, there is no doubt that they contribute greatly to artistic media such as music and film.

Exercises

Think about the ways in which video games have influenced and affected other forms of media. Then consider the following questions:

- Are there things video games will never be able to offer?

- Write down several examples of ways in which other forms of media are not replicated by video games. Then speculate on ways video games could eventually emulate these forms.

References

Associated Press, “‘Grand Theft Auto IV’ Beats ‘Iron Man’ by $300 Million,” Fox News, May 9, 2008, http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,354711,00.html.

Associated Press, “Military Training Is Just a Game,” Wired, October 3, 2003, http://www.wired.com/gaming/gamingreviews/news/2003/10/60688.

Bowditch, Gillian. “Grand Theft Auto Producer is Godfather of Gaming,” Times (London), April 27, 2008, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/scotland/article3821838.ece.

Box Office Mojo, “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider,” http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=tombraider.htm.

Box Office Mojo, “Mortal Kombat,” http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=mortalkombat.htm.

Brand, “Space War.”

Cohn & Wolfe Toronto, “Italian Plumber More Memorable Than Harper, Dion,” news release, November 13, 2007, http://www.newswire.ca/en/releases/mmnr/Super_Mario_Galaxy/index.html.

Ebert, Roger. “Video Games Can Never Be Art,” Chicago Sun-Times, April 16, 2010, http://blogs.suntimes.com/ebert/2010/04/video_games_can_never_be_art.html.

Entertainment Software Association, Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry: 2009 Sales, Demographic, and Usage Data, 2009, http://www.theesa.com/facts/pdfs/ESA_EF_2009.pdf.

Faylor, Chris. “NPD: 72% of U.S. Population Played Games in 2007; PC Named “Driving Force in Online Gaming,” Shack News, April 2, 2008, http://www.shacknews.com/onearticle.x/52025.

Feller, Ben. “Group: Video Games Can Reshape Education,” MSNBC, October 18, 2006, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15309615/from/ET/.

Fisher, Max. “Are Video Games Art?” Atlantic Wire, April 19, 2010, http://www.theatlanticwire.com/features/view/feature/Are-Video-Games-Art-1085/.

Green, C. Shawn. and Daphne Bavelier, “Action Video Game Modifies Visual Selective Attention,” Nature 423, no. 6939 (2003): 534–537.

Hadhazy, Adam. “’NASCAR of the Skies’ to Feature Video Game-Like Interactivity,” TechNewsDaily, April 26, 2010, http://www.technewsdaily.com/nascar-of-the-skies-to-feature-video-game-like-interactivity–0475/.

Internet Movie Database, “Pokémon,” http://www.imdb.com/.

Khan, Joseph P. “Berklee is Teaching Its Students to Compose Scores for Video Games,” Boston Globe, January 19, 2010, http://www.boston.com/news/education/higher/articles/2010/01/19/berklee_is_teaching_students_to_compose_scores_for_video_games/.

Konzack, Lars. “Geek Culture: The 3rd Counter-Culture,” (paper, FNG2006, Preston, England, June 26–28, 2006), http://www.scribd.com/doc/270364/Geek-Culture-The-3rd-CounterCulture.

Murphy, David. “Boy Scouts Develop ‘Vide Game’ Merit Badge,” PC Magazine, May 2, 2010, http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2363331,00.asp.

Play Symphony, Jason Michael Paul Productions, “About,” Play! A Video Game Symphony, http://www.play-symphony.com/about.php.

Rossignol, Jim. This Gaming Life: Travels in Three Cities (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2008), 17.

Sharp, Craig. “Geeks in Vogue: Top Ten Cinematic Nerds,” Film Shaft, April 26, 2010, http://www.filmshaft.com/geeks-in-vogue-top-ten-cinematic-nerds/.

Shields, Mike. “Nielsen: Video Games Approach 5th Network Status,” Adweek, March 25, 2009, http://www.adweek.com/aw/content_display/news/agency/e3i4f087b1aeac6f008d0ecadfeffe4a191.

Strickland, Jonathan. “How Machinima Works,” HowStuffWorks.com, http://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/machinima3.htm.

That Game Company, “Flower,” http://thatgamecompany.com/games/flower/.

Video Games Music Big Hit, “Video Games Music Big Hit,” Wilmington (NC) Morning Star, February 1, 1997, 36.

Wischnowsky, “Wii Bowling.”

Wolf, Richard. “Nation’s Soaring Deficit Calls for Painful Choices,” USA Today, April 14, 2010, http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2010-04-12-deficit_N.htm.

10.5 Controversial Issues

Learning Objectives

- Describe controversial issues related to modern video games.

- Analyze the issues and problems with rating electronic entertainment.

- Discuss the effects of video game addiction.

- Examine the gender issues surrounding video games.

The increasing realism and expanded possibilities of video games has inspired a great deal of controversy. However, even early games, though rudimentary and seemingly laughable nowadays, raised controversy over their depiction of adult themes. Although increased realism and graphics capabilities of contemporary video games have increased the shock value of in-game violence, international culture has been struggling to come to terms with video game violence since the dawn of video games.

Violence

Violence in video games has been controversial from their earliest days. Death Race, an arcade game released in 1976, encouraged drivers to run over stick figures, which then turned into Xs. Although the programmers claimed that the stick figures were not human, the game was controversial, making national news on the TV talk show Donahue and the TV news magazine 60 Minutes. Video games, regardless of their realism or lack thereof, had added a new potential to the world of games and entertainment: the ability to simulate murder.

The enhanced realism of video games in the 1990s accompanied a rise in violent games as companies expanded the market to target older demographics. A great deal of controversy exists over the influence of this kind of violence on children, and also over the rating system that is applied to video games. There are many stories of real-life violent acts involving video games. The 1999 Columbine High School massacre was quickly linked to the teenage perpetrators’ enthusiasm for video games. The families of Columbine victims brought a lawsuit against 25 video game companies, claiming that if the games had not existed, the massacre would not have happened (Ward, 2001). In 2008, a 17-year-old boy shot his parents after they took away his video game system, killing his mother (Harvey, 2009). Also in 2008, when six teens were arrested for attempted carjacking and robbery, they stated that they were reenacting scenes from Grand Theft Auto (Cochran, 2008).

There is no shortage of news stories that involve young men committing crimes relating to an obsession with video games. The controversy has not been resolved regarding the influences behind these crimes. Many studies have linked aggression to video games; however, critics take issue with using the results of these studies to claim that the video games caused the aggression. They point out that people who enact video-game–related crimes already have psychopathic tendencies, and that the results of such research studies are correlational rather than causational—a naturally violent person is drawn to play violent video games (Adams, 2010). Other critics point out that violent games are designed for adults, just as violent movies are, and that parents should enforce stricter standards for their children.

The problem of children’s access to violent games is a large and complex one. Video games present difficult issues for those who create the ratings. One problem is the inconsistency that seems to exist in rating video games and movies. Movies with violence or sexual themes are rated either R or NC-17. Filmmakers prefer the R rating over the NC-17 rating because NC-17 ratings hurt box office sales, and they will often heavily edit films to remove overly graphic content. The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), rates video games. The two most restrictive ratings the ESRB has put forth are “M” (for Mature; 17 and older; “may contain mature sexual themes, more intense violence, and/or strong language”) and “AO” (for Adults Only; 18 and up; “may include graphic depictions of sex and/or violence”). If this rating system were applied to movies, a great deal of movies now rated R would be labeled AO. An AO label can have a devastating effect on game sales; in fact, many retail outlets will not sell games with an AO rating (Hyman, 2005). This creates a situation where a video game with a sexual or violent scene as graphic as the ones seen in R-rated movies is difficult to purchase, whereas a pornographic magazine can be bought at many convenience stores. This issue reveals a unique aspect of video games. Although many of them are designed for adults, the distribution system and culture surrounding video games is still largely youth-oriented.

Video Game Addiction