Source Edition – Chapters 7-9

Chapter 7: Radio

7.1 Radio

7.2 Evolution of Radio Broadcasting

7.3 Radio Station Formats

7.4 Radio’s Impact on Culture

7.5 Radio’s New Future

7.1 Radio

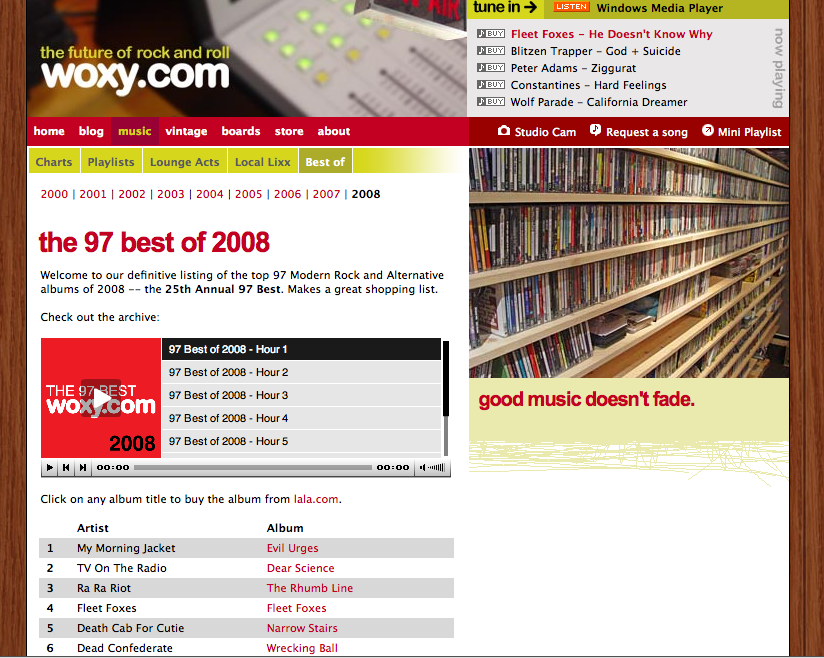

In 1983, radio station WOXY’s new owners bought the station and changed its format from Top 40 to the up-and-coming alternative rock format, kicking off with U2’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday (WOXY, 2009).” Then located in the basement of a fast-food restaurant in Ohio, the station was a risk for its purchasers, a husband and wife team who took a chance by changing the format to a relatively new one. Their investment paid off with the success of their station. By 1990, WOXY had grown in prestige to become one of Rolling Stone magazine’s top 15 radio stations in the country, and had even been made famous by a reference in the 1988 film Rain Man (Bishop, 2004). In 1998, the station launched a web cast and developed a national following, ranking 12th among Internet broadcasters for listenership in 2004 (Bishop, 2004).

When the station’s owners decided to retire and sell the frequency allocation in 2004, they hoped to find investors to continue the online streaming version of the station. After several months of unsuccessful searching, however, the station went off the air entirely—only to find a last-minute investor willing to fund an Internet version of the station (WOXY).

The online version of the station struggled to make ends meet until it was purchased by the online music firm Lala (Cheng, 2010). The now-defunct Lala sold WOXY to music company Future Sounds Inc., which moved the station and staff from Ohio to Austin, Texas. In March 2010, citing “current economic realities and the lack of ongoing funding,” WOXY.com went off the air with only a day’s notice (Cheng, 2010).

Taken in the context of the modern Internet revolution and the subsequent faltering of institutions such as newspapers and book publishers, the rise and fall of WOXY may seem to bode ill for the general fate of radio. However, taken in the larger context of radio’s history, this story of the Internet’s effect on radio could prove to be merely another leap in a long line of radio revolutions. From the shutting down of all broadcasts during World War I to the eclipse of radio by television during the 1950s, many arbiters of culture and business have prophesized the demise of radio for decades. Yet this chapter will show how the inherent flexibility and intimacy of the medium has allowed it to adapt to new market trends and to continue to have relevance as a form of mass communication.

References

Bishop, Lauren. “97X Farewell,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 10, 2004, http://www.enquirer.com/editions/2004/05/10/tem_tem1a.html.

Cheng, Jacqui. “Bad Luck, Funding Issues Shutter Indie Station WOXY.com,” Ars Technica (blog), March 23, 2010, http://arstechnica.com/media/news/2010/03/bad-luck-funding-issues-shutter-indie-station-woxycom.ars.

WOXY, “The History of WOXY,” 2009, http://woxy.com/about/.

WOXY, “The History.”

7.2 Evolution of Radio Broadcasting

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major technological changes in radio as a medium since its inception.

- Explain the defining characteristics of radio’s Golden Age.

- Describe the effects of networks and conglomerates on radio programming and culture.

At its most basic level, radio is communication through the use of radio waves. This includes radio used for person-to-person communication as well as radio used for mass communication. Both of these functions are still practiced today. Although most people associate the term radio with radio stations that broadcast to the general public, radio wave technology is used in everything from television to cell phones, making it a primary conduit for person-to-person communication.

The Invention of Radio

Guglielmo Marconi is often credited as the inventor of radio. As a young man living in Italy, Marconi read a biography of Hienrich Hertz, who had written and experimented with early forms of wireless transmission. Marconi then duplicated Hertz’s experiments in his own home, successfully sending transmissions from one side of his attic to the other (PBS). He saw the potential for the technology and approached the Italian government for support. When the government showed no interest in his ideas, Marconi moved to England and took out a patent on his device. Rather than inventing radio from scratch, however, Marconi essentially combined the ideas and experiments of other people to make them into a useful communications tool (Coe, 1996).

Figure 7.2

Guglielmo Marconi developed an early version of the wireless radio.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

In fact, long-distance electronic communication has existed since the middle of the 19th century. The telegraph communicated messages through a series of long and short clicks. Cables across the Atlantic Ocean connected even the far-distant United States and England using this technology. By the 1870s, telegraph technology had been used to develop the telephone, which could transmit an individual’s voice over the same cables used by its predecessor.

When Marconi popularized wireless technology, contemporaries initially viewed it as a way to allow the telegraph to function in places that could not be connected by cables. Early radios acted as devices for naval ships to communicate with other ships and with land stations; the focus was on person-to-person communication. However, the potential for broadcasting—sending messages to a large group of potential listeners—wasn’t realized until later in the development of the medium.

Broadcasting Arrives

The technology needed to build a radio transmitter and receiver was relatively simple, and the knowledge to build such devices soon reached the public. Amateur radio operators quickly crowded the airwaves, broadcasting messages to anyone within range and, by 1912, incurred government regulatory measures that required licenses and limited broadcast ranges for radio operation (White). This regulation also gave the president the power to shut down all stations, a power notably exercised in 1917 upon the United States’ entry into World War I to keep amateur radio operators from interfering with military use of radio waves for the duration of the war (White).

Wireless technology made radio as it is known today possible, but its modern, practical function as a mass communication medium had been the domain of other technologies for some time. As early as the 1880s, people relied on telephones to transmit news, music, church sermons, and weather reports. In Budapest, Hungary, for example, a subscription service allowed individuals to listen to news reports and fictional stories on their telephones (White). Around this time, telephones also transmitted opera performances from Paris to London. In 1909, this innovation emerged in the United States as a pay-per-play phonograph service in Wilmington, Delaware (White). This service allowed subscribers to listen to specific music recordings on their telephones (White).

In 1906, Massachusetts resident Reginald Fessenden initiated the first radio transmission of the human voice, but his efforts did not develop into a useful application (Grant, 1907). Ten years later, Lee de Forest used radio in a more modern sense when he set up an experimental radio station, 2XG, in New York City. De Forest gave nightly broadcasts of music and news until World War I halted all transmissions for private citizens (White).

Radio’s Commercial Potential

After the World War I radio ban lifted with the close of the conflict in 1919, a number of small stations began operating using technologies that had developed during the war. Many of these stations developed regular programming that included religious sermons, sports, and news (White). As early as 1922, Schenectady, New York’s WGY broadcast over 40 original dramas, showing radio’s potential as a medium for drama. The WGY players created their own scripts and performed them live on air. This same groundbreaking group also made the first known attempt at television drama in 1928 (McLeod, 1998).

Businesses such as department stores, which often had their own stations, first put radio’s commercial applications to use. However, these stations did not advertise in a way that the modern radio listener would recognize. Early radio advertisements consisted only of a “genteel sales message broadcast during ‘business’ (daytime) hours, with no hard sell or mention of price (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).” In fact, radio advertising was originally considered an unprecedented invasion of privacy, because—unlike newspapers, which were bought at a newsstand—radios were present in the home and spoke with a voice in the presence of the whole family (Sterling & Kittross, 2002). However, the social impact of radio was such that within a few years advertising was readily accepted on radio programs. Advertising agencies even began producing their own radio programs named after their products. At first, ads ran only during the day, but as economic pressure mounted during the Great Depression in the 1930s, local stations began looking for new sources of revenue, and advertising became a normal part of the radio soundscape (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).

The Rise of Radio Networks

Not long after radio’s broadcast debut, large businesses saw its potential profitability and formed networks. In 1926, RCA started the National Broadcasting Network (NBC). Groups of stations that carried syndicated network programs along with a variety of local shows soon formed its Red and Blue networks. Two years after the creation of NBC, the United Independent Broadcasters became the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) and began competing with the existing Red and Blue networks (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).

Although early network programming focused mainly on music, it soon developed to include other programs. Among these early innovations was the variety show. This format generally featured several different performers introduced by a host who segued between acts. Variety shows included styles as diverse as jazz and early country music. At night, dramas and comedies such as Amos ’n’ Andy, The Lone Ranger, and Fibber McGee and Molly filled the airwaves. News, educational programs, and other types of talk programs also rose to prominence during the 1930s (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).

The Radio Act of 1927

In the mid-1920s, profit-seeking companies such as department stores and newspapers owned a majority of the nation’s broadcast radio stations, which promoted their owners’ businesses (ThinkQuest). Nonprofit groups such as churches and schools operated another third of the stations. As the number of radio stations outgrew the available frequencies, interference became problematic, and the government stepped into the fray.

The Radio Act of 1927 established the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) to oversee regulation of the airwaves. A year after its creation, the FRC reallocated station bandwidths to correct interference problems. The organization reserved 40 high-powered channels, setting aside 37 of these for network affiliates. The remaining 600 lower-powered bandwidths went to stations that had to share the frequencies; this meant that as one station went off the air at a designated time, another one began broadcasting in its place. The Radio Act of 1927 allowed major networks such as CBS and NBC to gain a 70 percent share of U.S. broadcasting by the early 1930s, earning them $72 million in profits by 1934 (McChesney, 1992). At the same time, nonprofit broadcasting fell to only 2 percent of the market (McChesney, 1992).

In protest of the favor that the 1927 Radio Act showed toward commercial broadcasting, struggling nonprofit radio broadcasters created the National Committee on Education by Radio to lobby for more outlets. Basing their argument on the notion that the airwaves—unlike newspapers—were a public resource, they asserted that groups working for the public good should take precedence over commercial interests. Nevertheless, the Communications Act of 1934 passed without addressing these issues, and radio continued as a mainly commercial enterprise (McChesney, 1992).

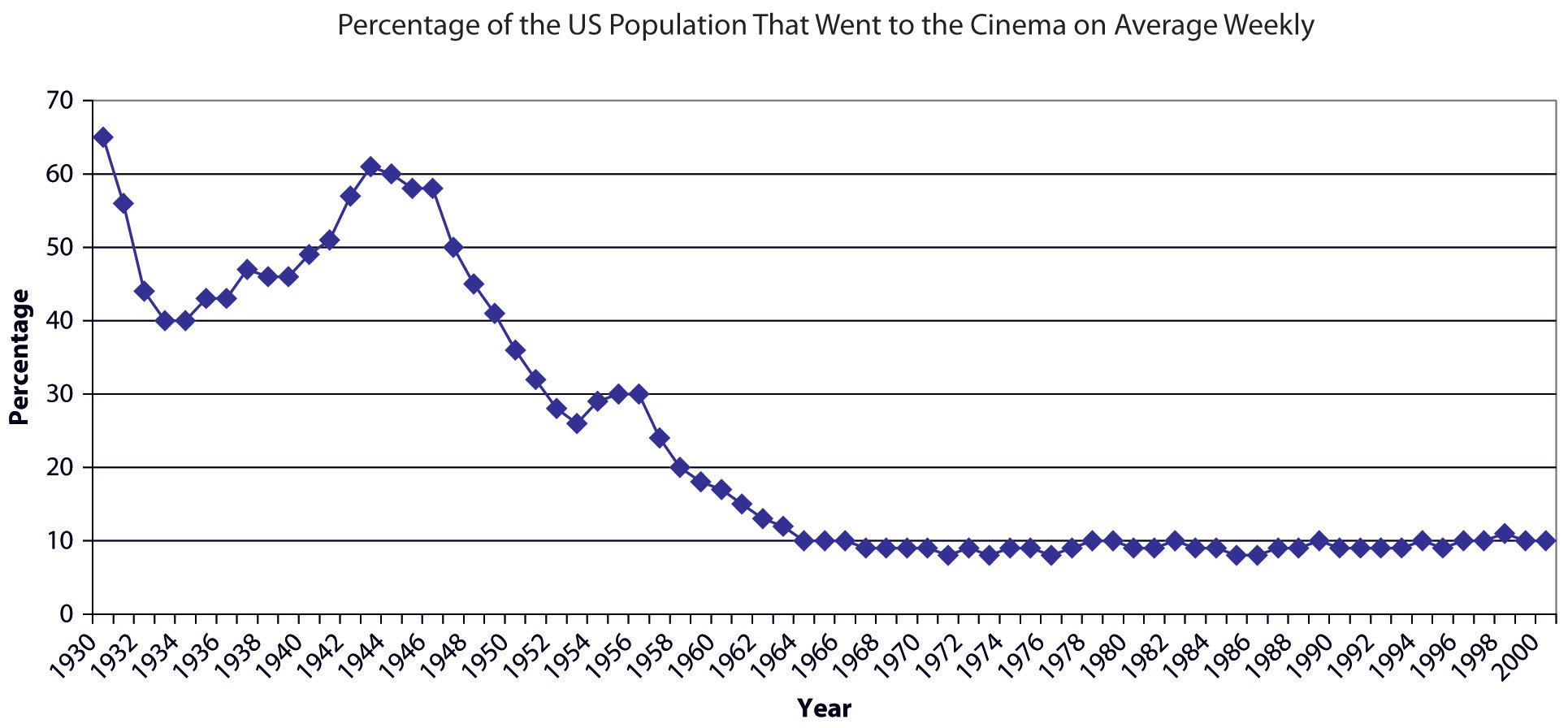

The Golden Age of Radio

The so-called Golden Age of Radio occurred between 1930 and the mid-1950s. Because many associate the 1930s with the struggles of the Great Depression, it may seem contradictory that such a fruitful cultural occurrence arose during this decade. However, radio lent itself to the era. After the initial purchase of a receiver, radio was free and so provided an inexpensive source of entertainment that replaced other, more costly pastimes, such as going to the movies.

Radio also presented an easily accessible form of media that existed on its own schedule. Unlike reading newspapers or books, tuning in to a favorite program at a certain time became a part of listeners’ daily routine because it effectively forced them to plan their lives around the dial.

Daytime Radio Finds Its Market

During the Great Depression, radio became so successful that another network, the Mutual Broadcasting Network, began in 1934 to compete with NBC’s Red and Blue networks and the CBS network, creating a total of four national networks (Cashman, 1989). As the networks became more adept at generating profits, their broadcast selections began to take on a format that later evolved into modern television programming. Serial dramas and programs that focused on domestic work aired during the day when many women were at home. Advertisers targeted this demographic with commercials for domestic needs such as soap (Museum). Because they were often sponsored by soap companies, daytime serial dramas soon became known as soap operas. Some modern televised soap operas, such as Guiding Light, which ended in 2009, actually began in the 1930s as radio serials (Hilmes, 1999).

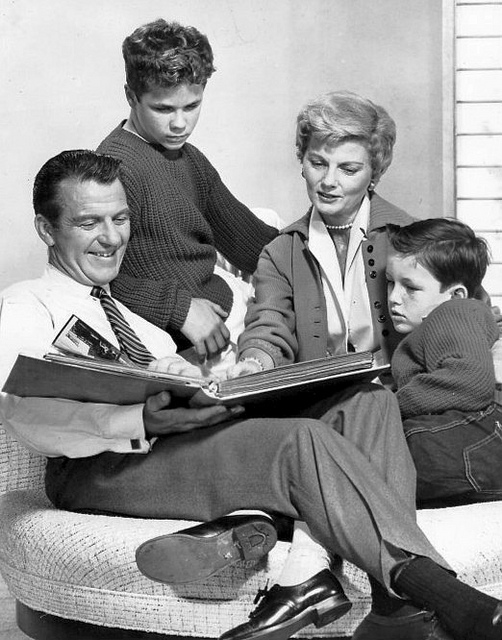

The Origins of Prime Time

During the evening, many families listened to the radio together, much as modern families may gather for television’s prime time. Popular evening comedy variety shows such as George Burns and Gracie Allen’s Burns and Allen, the Jack Benny Show, and the Bob Hope Show all began during the 1930s. These shows featured a central host—for whom the show was often named—and a series of sketch comedies, interviews, and musical performances, not unlike contemporary programs such as Saturday Night Live. Performed live before a studio audience, the programs thrived on a certain flair and spontaneity. Later in the evening, so-called prestige dramas such as Lux Radio Theater and Mercury Theatre on the Air aired. These shows featured major Hollywood actors recreating movies or acting out adaptations of literature (Hilmes).

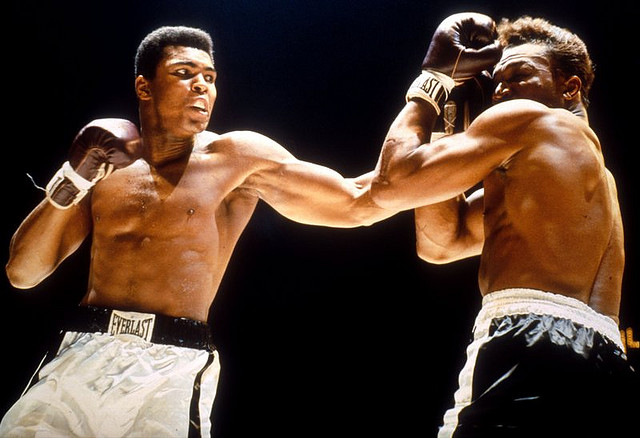

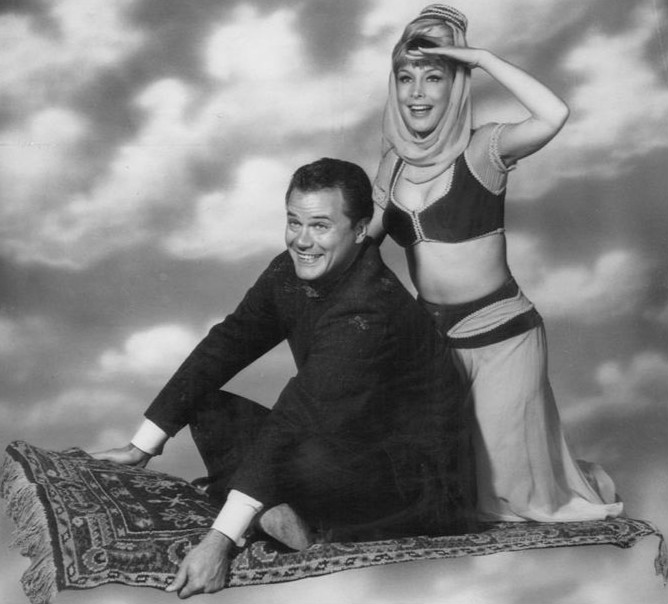

Figure 7.3

Many prime-time radio broadcasts featured film stars recreating famous films over the air.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Instant News

By the late 1930s, the popularity of radio news broadcasts had surpassed that of newspapers. Radio’s ability to emotionally draw its audiences in close to events made for news that evoked stronger responses and, thus, greater interest than print news could. For example, the infant son of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh was kidnapped and murdered in 1932. Radio networks set up mobile stations that covered events as they unfolded, broadcasting nonstop for several days and keeping listeners updated on every detail while tying them emotionally to the outcome (Brown, 1998).

As recording technology advanced, reporters gained the ability to record events in the field and bring them back to the studio to broadcast over the airwaves. One early example of this was Herb Morrison’s recording of the Hindenburg disaster. In 1937, the Hindenburg blimp exploded into flames while attempting to land, killing 37 of its passengers. Morrison was already on the scene to record the descent, capturing the fateful crash. The entire event was later broadcast, including the sound of the exploding blimp, providing listeners with an unprecedented emotional connection to a national disaster. Morrison’s exclamation “Oh, the humanity!” became a common phrase of despair after the event (Brown, 1998).

Radio news became even more important during World War II, when programs such as Norman Corwin’s This Is War! sought to bring more sober news stories to a radio dial dominated by entertainment. The program dealt with the realities of war in a somber manner; at the beginning of the program, the host declared, “No one is invited to sit down and take it easy. Later, later, there’s a war on (Horten, 2002).” In 1940, Edward R. Murrow, a journalist working in England at the time, broadcast firsthand accounts of the German bombing of London, giving Americans a sense of the trauma and terror that the English were experiencing at the outset of the war (Horten, 2002). Radio news outlets were the first to broadcast the attack on Pearl Harbor that propelled the United States into World War II in 1941. By 1945, radio news had become so efficient and pervasive that when Roosevelt died, only his wife, his children, and Vice President Harry S. Truman were aware of it before the news was broadcast over the public airwaves (Brown).

The Birth of the Federal Communications Commission

The Communications Act of 1934 created the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and ushered in a new era of government regulation. The organization quickly began enacting influential radio decisions. Among these was the 1938 decision to limit stations to 50,000 watts of broadcasting power, a ceiling that remains in effect today (Cashman). As a result of FCC antimonopoly rulings, RCA was forced to sell its NBC Blue network; this spun-off division became the American Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) in 1943 (Brinson, 2004).

Another significant regulation with long-lasting influence was the Fairness Doctrine. In 1949, the FCC established the Fairness Doctrine as a rule stating that if broadcasters editorialized in favor of a position on a particular issue, they had to give equal time to all other reasonable positions on that issue (Browne & Browne, 1986). This tenet came from the long-held notion that the airwaves were a public resource, and that they should thus serve the public in some way. Although the regulation remained in effect until 1987, the impact of its core concepts are still debated. This chapter will explore the Fairness Doctrine and its impact in greater detail in a later section.

Radio on the Margins

Despite the networks’ hold on programming, educational stations persisted at universities and in some municipalities. They broadcast programs such as School of the Air and College of the Air as well as roundtable and town hall forums. In 1940, the FCC reserved a set of frequencies in the lower range of the FM radio spectrum for public education purposes as part of its regulation of the new spectrum. The reservation of FM frequencies gave educational stations a boost, but FM proved initially unpopular due to a setback in 1945, when the FCC moved the FM bandwidth to a higher set of frequencies, ostensibly to avoid problems with interference (Longley, 1968). This change required the purchase of new equipment by both consumers and radio stations, thus greatly slowing the widespread adoption of FM radio.

One enduring anomaly in the field of educational stations has been the Pacifica Radio network. Begun in 1949 to counteract the effects of commercial radio by bringing educational programs and dialogue to the airwaves, Pacifica has grown from a single station—Berkeley, California’s KPFA—to a network of five stations and more than 100 affiliates (Pacifica Network). From the outset, Pacifica aired newer classical, jazz, and folk music along with lectures, discussions, and interviews with public artists and intellectuals. Among Pacifica’s major innovations was its refusal to take money from commercial advertisers, relying instead on donations from listeners and grants from institutions such as the Ford Foundation and calling itself listener-supported (Mitchell, 2005).

Another important innovation on the fringes of the radio dial during this time was the growth of border stations. Located just across the Mexican border, these stations did not have to follow FCC or U.S. regulatory laws. Because the stations broadcast at 250,000 watts and higher, their listening range covered much of North America. Their content also diverged—at the time markedly—from that of U.S. stations. For example, Dr. John Brinkley started station XERF in Del Rio, Mexico, after being forced to shut down his station in Nebraska, and he used the border station in part to promote a dubious goat gland operation that supposedly cured sexual impotence (Dash, 2008). Besides the goat gland promotion, the station and others like it often carried music, like country and western, that could not be heard on regular network radio. Later border station disc jockeys, such as Wolfman Jack, were instrumental in bringing rock and roll music to a wider audience (Rudel, 2008).

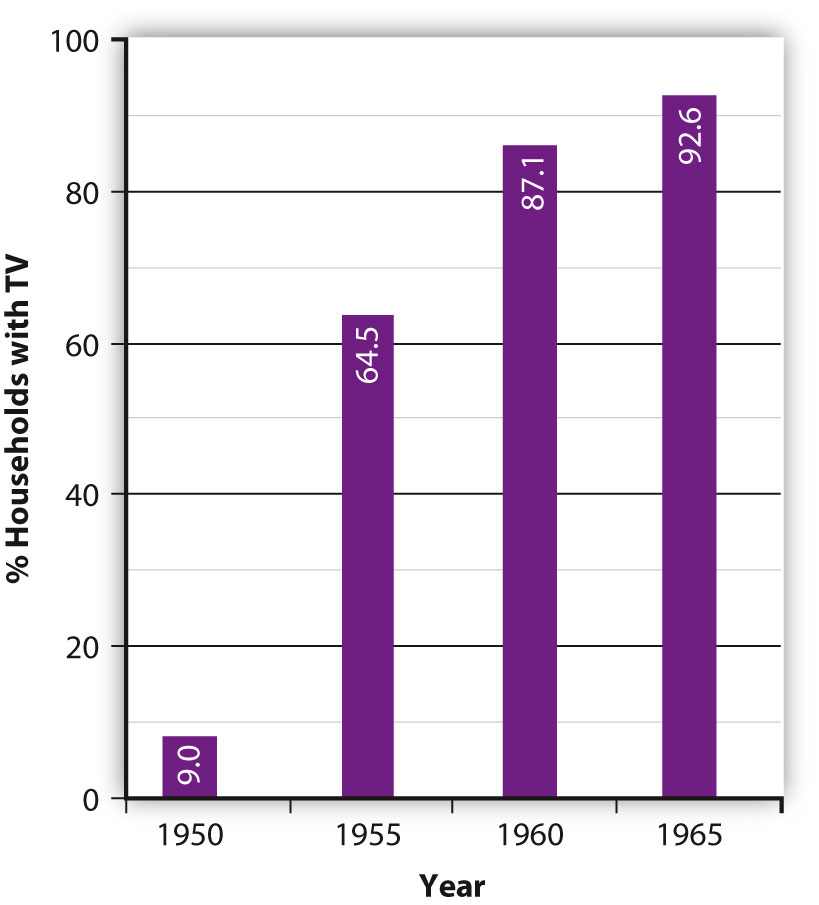

Television Steals the Show

A great deal of radio’s success as a medium during the 1920s and 1930s was due to the fact that no other medium could replicate it. This changed in the late 1940s and early 1950s as television became popular. A 1949 poll of people who had seen television found that almost half of them believed that radio was doomed (Gallup, 1949). Television sets had come on the market by the late 1940s, and by 1951, more Americans were watching television during prime time than ever (Bradley). Famous radio programs such as The Bob Hope Show were made into television shows, further diminishing radio’s unique offerings (Cox, 1949).

Surprisingly, some of radio’s most critically lauded dramas launched during this period. Gunsmoke, an adult-oriented Western show (that later become television’s longest-running show) began in 1952; crime drama Dragnet, later made famous in both television and film, broadcast between 1949 and 1957; and Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar aired from 1949 to 1962, when CBS canceled its remaining radio dramas. However, these respected radio dramas were the last of their kind (Cox, 2002). Although radio was far from doomed by television, its Golden Age was.

Transition to Top 40

As radio networks abandoned the dramas and variety shows that had previously sustained their formats, the soundscape was left to what radio could still do better than any other mass medium: play music. With advertising dollars down and the emergence of better recording formats, it made good business sense for radio to focus on shows that played prerecorded music. As strictly music stations began to rise, new innovations to increase their profitability appeared. One of the most notable and far-reaching of these innovations was the Top 40 station, a concept that supposedly came from watching jukebox patrons continually play the same songs (Brewster & Broughton, 2000). Robert Storz and Gordon McLendon began adapting existing radio stations to fit this new format with great success. In 1956, the creation of limited playlists further refined the format by providing about 50 songs that disc jockeys played repeatedly every day. By the early 1960s, many stations had developed limited playlists of only 30 songs (Walker, 2001).

Another musically fruitful innovation came with the increase of Black disc jockeys and programs created for Black audiences. Because its advertisers had nowhere to go in a media market dominated by White performers, Black radio became more common on the AM dial. As traditional programming left radio, disc jockeys began to develop as the medium’s new personalities, talking more in between songs and developing followings. Early Black disc jockeys even began improvising rhymes over the music, pioneering techniques that later became rap and hip-hop. This new personality-driven style helped bring early rock and roll to new audiences (Walker, 2001).

FM: The High-Fidelity Counterculture

As music came to rule the airwaves, FM radio drew in new listeners because of its high-fidelity sound capabilities. When radio had primarily featured dramas and other talk-oriented formats, sound quality had simply not mattered to many people, and the purchase of an FM receiver did not compete with the purchase of a new television in terms of entertainment value. As FM receivers decreased in price and stereo recording technology became more popular, however, the high-fidelity trend created a market for FM stations. Mostly affluent consumers began purchasing component stereos with the goal of getting the highest sound quality possible out of their recordings (Douglas, 2004). Although this audience often preferred classical and jazz stations to Top 40 radio, they were tolerant of new music and ideas (Douglas, 2004).

Both the high-fidelity market and the growing youth counterculture of the 1960s had similar goals for the FM spectrum. Both groups eschewed AM radio because of the predictable programming, poor sound quality, and over-commercialization. Both groups wanted to treat music as an important experience rather than as just a trendy pastime or a means to make money. Many adherents to the youth counterculture of the 1960s came from affluent, middle-class families, and their tastes came to define a new era of consumer culture. The goals and market potential of both the high-fidelity lovers and the youth counterculture created an atmosphere on the FM dial that had never before occurred (Douglas, 2004).

Between the years 1960 and 1966, the number of households capable of receiving FM transmissions grew from about 6.5 million to some 40 million. The FCC also aided FM by issuing its nonduplication ruling in 1964. Before this regulation, many AM stations had other stations on the FM spectrum that simply duplicated the AM programming. The nonduplication rule forced FM stations to create their own fresh programming, opening up the spectrum for established networks to develop new stations (Douglas, 2004).

The late 1960s saw new disc jockeys taking greater liberties with established practices; these liberties included playing several songs in a row before going to a commercial break or airing album tracks that exceeded 10 minutes in length. University stations and other nonprofit ventures to which the FCC had given frequencies during the late 1940s popularized this format, and, in time, commercial stations tried to duplicate their success by playing fewer commercials and by allowing their disc jockeys to have a say in their playlists. Although this made for popular listening formats, FM stations struggled to make the kinds of profits that the AM spectrum drew (Douglas, 2004).

In 1974, FM radio accounted for one-third of all radio listening but only 14 percent of radio profits (Douglas, 2004). Large network stations and advertisers began to market heavily to the FM audience in an attempt to correct this imbalance. Stations began tightening their playlists and narrowing their formats to please advertisers and to generate greater revenues. By the end of the 1970s, radio stations were beginning to play specific formats, and the progressive radio of the previous decade had become difficult to find (Douglas, 2004).

The Rise of Public Radio

After the Golden Age of Radio came to an end, most listeners tuned in to radio stations to hear music. The variety shows and talk-based programs that had sustained radio in early years could no longer draw enough listeners to make them a successful business proposition. One divergent path from this general trend, however, was the growth of public radio.

Groups such as the Ford Foundation had funded public media sources during the early 1960s. When the foundation decided to withdraw its funding in the middle of the decade, the federal government stepped in with the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. This act created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) and charged it with generating funding for public television and radio outlets. The CPB in turn created National Public Radio (NPR) in 1970 to provide programming for already-operating stations. Until 1982, in fact, the CPB entirely and exclusively funded NPR. Public radio’s first program was All Things Considered, an evening news program that focused on analysis and interpretive reporting rather than cutting-edge coverage. In the mid-1970s, NPR attracted Washington-based journalists such as Cokie Roberts and Linda Wertheimer to its ranks, giving the coverage a more professional, hard-reporting edge (Schardt, 1996).

However, in 1983, public radio was pushed to the brink of financial collapse. NPR survived in part by relying more on its member stations to hold fundraising drives, now a vital component of public radio’s business model. In 2003, Joan Kroc, the widow of McDonald’s CEO and philanthropist Ray Kroc, bequeathed a grant of over $200 million to NPR that may keep it afloat for many years to come.

Having weathered the financial storm intact, NPR continued its progression as a respected news provider. During the first Gulf War, NPR sent out correspondents for the first time to provide in-depth coverage of unfolding events. Public radio’s extensive coverage of the 2001 terrorist bombings gained its member stations many new listeners, and it has since expanded (Clift, 2011). Although some have accused NPR of presenting the news with a liberal bias, its listenership in 2005 was 28 percent conservative, 32 percent liberal, and 29 percent moderate. Newt Gingrich, a conservative Republican and former speaker of the house, has stated that the network is “a lot less on the left” than some may believe (Sherman, 2005). With more than 26 million weekly listeners and 860 member stations in 2009, NPR has become a leading radio news source (Kamenetz, 2009).

Public radio distributors such as Public Radio International (PRI) and local public radio stations such as WBEZ in Chicago have also created a number of cultural and entertainment programs, including quiz shows, cooking shows, and a host of local public forum programs. Storytelling programs such as This American Life have created a new kind of free-form radio documentary genre, while shows such as PRI’s variety show A Prairie Home Companion have revived older radio genres. This variety of popular public radio programming has shifted radio from a music-dominated medium to one that is again exploring its vast potential.

Conglomerates

During the early 1990s, many radio stations suffered the effects of an economic recession. Some stations initiated local marketing agreements (LMAs) to share facilities and resources amid this economic decline. LMAs led to consolidation in the industry as radio stations bought other stations to create new hubs for the same programming. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 further increased consolidation by eliminating a duopoly rule prohibiting dual station ownership in the same market and by lifting the numerical limits on station ownership by a single entity.

As large corporations such as Clear Channel Communications bought up stations around the country, they reformatted stations that had once competed against one another so that each focused on a different format. This practice led to mainstream radio’s present state, in which narrow formats target highly specific demographic audiences.

Ultimately, although the industry consolidation of the 1990s made radio profitable, it reduced local coverage and diversity of programming. Because stations around the country served as outlets for a single network, the radio landscape became more uniform and predictable (Keith, 2010). Much as with chain restaurants and stores, some people enjoy this type of predictability, while others prefer a more localized, unique experience (Keith, 2010).

Key Takeaways

- The Golden Age of Radio covered the period between 1930 and 1950. It was characterized by radio’s overwhelming popularity and a wide range of programming, including variety, music, drama, and theater programs.

- Top 40 radio arose after most nonmusic programming moved to television. This format used short playlists of popular hits and gained a great deal of commercial success during the 1950s and 1960s.

- FM became popular during the late 1960s and 1970s as commercial stations adopted the practices of free-form stations to appeal to new audiences who desired higher fidelity and a less restrictive format.

- Empowered by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, media conglomerates have subsumed unprecedented numbers of radio stations by single companies. Radio station consolidation brings predictability and profits at the expense of unique programming.

Exercises

Please respond to the following short-answer writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Explain the advantages that radio had over traditional print media during the 1930s and 1940s.

- Do you think that radio could experience another golden age? Explain your answer.

- How has the consolidation of radio stations affected radio programming?

- Characterize the overall effects of one significant technological or social shift described in this section on radio as a medium.

References

Bradley, Becky. “American Cultural History: 1950–1959,” Lone Star College, Kingwood, http://kclibrary.lonestar.edu/decade50.html.

Brewster, Bill and Frank Broughton, Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey, (New York: Grove Press, 2000), 48.

Brinson, Susan. The Red Scare, Politics, and the Federal Communications Commission, 1941–1960 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004), 42.

Brown, Manipulating the Ether, 123.

Brown, Robert. Manipulating the Ether: The Power of Broadcast Radio in Thirties America (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland, 1998), 134–137.

Browne, Ray and Glenn Browne, Laws of Our Fathers: Popular Culture and the U.S. Constitution (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1986), 132.

Cashman, America in the Twenties and Thirties, 327.

Cashman, Sean. America in the Twenties and Thirties: The Olympian Age of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (New York: New York University Press, 1989), 328.

Clift, Nick. “Viewpoint: Protect NPR, It Protects Us,” Michigan Daily, February 15, 2011, http://www.michigandaily.com/content/viewpoint-npr.

Coe, Lewis. Wireless Radio: A Brief History (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland, 1996), 4–10.

Cox, Jim. American Radio Networks: A History (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland, 2009), 171–175.

Cox, Jim. Say Goodnight, Gracie: The Last Years of Network Radio (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland, 2002), 39–41.

Dash, Mike. “John Brinkley, the goat-gland quack,” The Telegraph, April 18, 2008, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/non_fictionreviews/3671561/John-Brinkley-the-goat-gland-quack.html.

Douglas, Susan. Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 266–268.

Gallup, George. “One-Fourth in Poll Think Television Killing Radio,” Schenectady (NY) Gazette, June 8, 1949, http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=d3YuAAAAIBAJ&sjid=loEFAAAAIBAJ&pg=840,1029432&dq=radio-is-doomed&hl=en.

Grant, John. Experiments and Results in Wireless Telegraphy (reprinted from The American Telephone Journal, 49–51, January 26, 1907), http://earlyradiohistory.us/1907fes.htm.

Hilmes, Radio Voices, 183–185.

Hilmes, Michele. Radio Voices: American Broadcasting 1922–1952 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 157.

Horten, Gerd. Radio Goes to War: The Cultural Politics of Propaganda During World War II (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2002), 48–52.

Kamenetz, Anya. “Will NPR Save the News?” Fast Company, April 1, 2009, http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/134/finely-tuned.html.

Keith, Michael. The Radio Station: Broadcast, Satellite and Internet (Burlington, MA: Focal Press, 2010), 17–24.

Longley, Lawrence D. “The FM Shift in 1945,” Journal of Broadcasting 12, no. 4 (1968): 353–365.

McChesney, Robert W. “Media and Democracy: The Emergence of Commercial Broadcasting in the United States, 1927–1935,” in “Communication in History: The Key to Understanding,” OAH Magazine of History 6, no. 4 (1992).

McLeod, Elizabeth. “The WGY Players and the Birth of Radio Drama,” 1998, http://www.midcoast.com/~lizmcl/wgy.html.

Mitchell, Jack. Listener Supported: The Culture and History of Public Radio (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2005), 21–24.

Museum, “Soap Opera,” The Museum of Broadcast Communications, http://www.museum.tv/eotvsection.php?entrycode=soapopera.

Pacifica Network, “Pacifica Network Stations,” The Pacifica Foundation, http://pacificanetwork.org/radio/content/section/7/42/.

PBS, “Guglielmo Marconi,” American Experience: People & Events, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/rescue/peopleevents/pandeAMEX98.html.

Rudel, Anthony. Hello, Everybody! The Dawn of American Radio (Orlando, FL: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008), 130–132.

Schardt, Sue. “Public Radio—A Short History,” Christian Science Monitor Publishing Company, 1996, http://www.wsvh.org/pubradiohist.htm.

Sherman, Scott. “Good, Gray NPR,” The Nation, May 23, 2005, 34–38.

Sterling, Christopher and John Kittross, Stay Tuned: A History of American Broadcasting, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2002), 124.

ThinkQuest, “Radio’s Emergence,” Oracle ThinkQuest: The 1920s, http://library.thinkquest.org/27629/themes/media/md20s.html.

Walker, Jesse. Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America (New York: New York University Press, 2001), 56.

White, “Broadcasting After World War I (1919–1921),” United States Early Radio History, http://earlyradiohistory.us/sec016.htm.

White, “News and Entertainment by Telephone (1876–1925),” United States Early Radio History, http://earlyradiohistory.us/sec003.htm.

White, “Pre-War Vacuum Tube Transmitter Development 1914–1917),” United States Early Radio History, http://earlyradiohistory.us/sec011.htm.

White, Thomas. “Pioneering Amateurs (1900–1917),” United States Early Radio History, http://earlyradiohistory.us/sec012.htm.

7.3 Radio Station Formats

Learning Objectives

- Describe the use of radio station formats in the development of modern stations.

- Analyze the effects of formats on radio programming.

Early radio network programming laid the groundwork for television’s format, with many different programs that appealed to a variety of people broadcast at different times of the day. As television’s popularity grew, however, radio could not compete and so it turned to fresh programming techniques. A new type of format-driven station became the norm. Propelled by the development of new types of music such as psychedelic rock and smooth jazz, the evolution of radio station formats took place. Since the beginning of this shift, different stations have tended to focus on the music that certain demographics preferred. For example, many people raised on Top 40 radio of the 1950s and 1960s did not necessarily want to hear modern pop hits, so stations playing older popular songs emerged to meet their needs.

Modern formats take into account aging generations, with certain stations specifically playing the pop hits of the 1950s and early 1960s, and others focusing on the pop hits of the late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. These formats have developed to target narrow, defined audiences with predictable tastes and habits. Ratings services such as Arbitron can identify the 10-year age demographic, the education level, and even the political leanings of listeners who prefer a particular format. Because advertisers want their commercials to reach an audience likely to buy their products, this kind of audience targeting is crucial for advertising revenue.

Top Radio Formats

The following top radio formats and their respective statistics were determined by an Arbitron survey that was released in 2010 (Arbitron Inc., 2010). The most popular formats and subformats cover a wide range of demographics, revealing radio’s wide appeal.

Country

Country music as a format includes stations devoted both to older and newer country music. In 2010, the country music format stood as the most popular radio format, beating out even such prominent nonmusic formats as news and talk. The format commanded the greatest listener share and the second largest number of stations dedicated to the style. Favored in rural regions of the country, the country music format—featuring artists like Keith Urban, the Dixie Chicks, and Tim McGraw—appeals to both male and female listeners from a variety of income levels (Arbitron Inc., 2010).

News/Talk/Information

The news/talk/information format includes AM talk radio, public radio stations with talk programming, network news radio, sports radio, and personality talk radio. This format reached nearly 59 million listeners in 2010, appealing particularly to those aged 65 and older; over 70 percent of its listeners had attended college. These listeners also ranked the highest among formats in levels of home ownership (Arbitron Inc., 2010).

Adult Contemporary

Generally targeted toward individuals over 30, the adult contemporary (AC) format favors pop music from the last 15 to 20 years as opposed to current hits. Different subformats, such as hot AC and modern AC, target younger audiences by playing songs that are more current. In 2010, the majority of AC audience were affluent, married individuals divided roughly along the national average politically. Adult contemporary listeners ranked highest by format in at-work listening. Hot AC, a subformat of AC that plays more current hits, ranked seventh in the nation. Urban AC, a version of AC that focuses on older R&B hits, ranked eighth in the nation in 2010 (Arbitron Inc., 2010).

Pop Contemporary Hit Radio

Pop contemporary hit radio, or pop CHR, is a subformat of contemporary hit radio (CHR). Other subformats of CHR include dance CHR and rhythmic CHR. Branded in the 1980s, this format encompasses stations that have a Top 40 orientation but draw on a wide number of formats, such as country, rock, and urban (Ford, 2008). In 2010, pop CHR ranked first among teenaged listeners, with 65 percent of its overall listeners aged under 35. This music, ranging from popular artists like Taylor Swift and Kanye West to Shakira, was played in the car more than at home or work, and saw its largest listening times in the evenings. Rhythmic CHR, a subformat focusing on a mix of rhythmic pop, R&B, dance, and hip-hop hits, also ranked high in 2010 (Arbitron).

Classic Rock

Classic rock stations generally play rock singles from the 1970s and 1980s, like “Stairway to Heaven,” by Led Zeppelin, and “You Shook Me All Night Long,” by AC/DC. Another distinct but similar format is album-oriented rock (AOR). This format focuses on songs that were not necessarily released as singles, also known as album cuts (Radio Station World). In 2010, classic rock stations ranked fifth in listener figures. These individuals were overwhelmingly men (70 percent) between the ages of 35 and 54 (54 percent). Classic rock was most often listened to in the car and at work, with only 26 percent of its listeners tuning in at home (Arbitron).

Urban Contemporary

The urban contemporary format plays modern hits from mainly Black artists—such as Lil Wayne, John Legend, and Ludacris—featuring a mix of soul, hip-hop, and R&B. In 2010, the format ranked eleventh in the nation. Urban contemporary focuses on listeners in the 18–34 age range (Arbitron).

Mexican Regional

The Mexican regional format is devoted to Spanish-language music, particularly Mexican and South American genres. In 2010, it ranked thirteenth in the nation and held the top spot in Los Angeles, a reflection of the rise in immigration from Mexico, Central America, and South America. Mexican regional’s listener base was over 96 percent Hispanic, and the format was most popular in the Western and Southwestern regions of the country. However, it was less popular in the Eastern regions of the country; in New England, for example, the format held a zero percent share of listening. The rise of the Mexican regional format illustrates the ways in which radio can change rapidly to meet new demographic trends (Arbitron).

An increasingly Spanish language–speaking population in the United States has also resulted in a number of distinct Spanish-language radio formats. These include Spanish oldies, Spanish adult hits, Spanish religious, Spanish tropical, and Spanish talk among others. Tejano, a type of music developed in Hispanic Texan communities, has also gained enough of an audience to become a dedicated format (Arbitron).

Other Popular Formats

Radio formats have become so specialized that ratings group Arbitron includes more than 50 designations. What was once simply called rock music has been divided into such subformats as alternative and modern rock. Alternative rock began as a format played on college stations during the 1980s but developed as a mainstream format during the following decade, thanks in part to the popular grunge music of that era. As this music aged, stations began using the term modern rock to describe a format dedicated to new rock music. This format has also spawned the active rock format, which plays modern rock hits with older rock hits thrown in (Radio Station World).

Nostalgia formats have split into a number of different formats as well. Oldies stations now generally focus on hits from the 1950s and 1960s, while the classic hits format chooses from hits of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Urban oldies, which focuses on R&B, soul, and other urban music hits from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, has also become a popular radio format. Formats such as adult hits mix older songs from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s with a small selection of popular music, while formats such as ’80s hits picks mainly from the 1980s (Radio Station World).

Radio station formats are an interesting way to look at popular culture in the United States. The evolution of nostalgia formats to include new decades nods to the size and tastes of the nation’s aging listeners. Hits of the 1980s are popular enough with their demographic to have entire stations dedicated to them, while other generations prefer stations with a mix of decades. The rise of the country format and the continued popularity of the classic rock format are potential indicators of cultural trends.

Key Takeaways

- Radio station formats target demographics that can generate advertising revenue.

- Contemporary hit radio was developed as a Top 40 format that expanded beyond strictly pop music to include country, rock, and urban formats.

- Spanish-language formats have grown in recent years, with Mexican regional moving into the top 10 formats in 2008.

- Nostalgia genres have developed to reflect the tastes of aging listeners, ranging from mixes of music from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s with current hits to formats that pick strictly from the 1980s.

Exercises

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- What is the purpose of radio station formats?

- How have radio station formats affected the way that modern stations play music?

- Pick a format, such as country or classic rock, and speculate on the reasons for its popularity.

References

Arbitron Inc., Radio Today: How America Listens to Radio, 2010.

Arbitron, Radio Today, 27–30.

Arbitron, Radio Today, 32–34.

Ford, John. “Contemporary Hit Radio,” September 2, 2008, http://radioindustry.suite101.com/article.cfm/contemporary_hit_radio_history.

Radio Station World, “Oldies, Adult Hits, and Nostalgia Radio Formats,” Radio Station World, 1996–2010, http://radiostationworld.com/directory/radio_formats/radio_formats_oldies.asp.

Radio Station World, “Rock and Alternative Music Formats,” Radio Station World, 1996–2010, http://radiostationworld.com/directory/Radio_Formats/radio_formats_rock.asp.

Radio Station World, “Rock and Alternative Music Formats,” Radio Station World.

7.4 Radio’s Impact on Culture

Learning Objectives

- Analyze radio as a form of mass media.

- Describe the effects of radio on the spread of different types of music.

- Analyze the effects of the Fairness Doctrine on political radio.

- Formulate opinions on controversial issues in radio.

Since its inception, radio’s impact on American culture has been immense. Modern popular culture is unthinkable without the early influence of radio. Entire genres of music that are now taken for granted, such as country and rock, owe their popularity and even existence to early radio programs that publicized new forms.

A New Kind of Mass Media

Mass media such as newspapers had been around for years before the existence of radio. In fact, radio was initially considered a kind of disembodied newspaper. Although this idea gave early proponents a useful, familiar way to think about radio, it underestimated radio’s power as a medium. Newspapers had the potential to reach a wide audience, but radio had the potential to reach almost everyone. Neither illiteracy nor even a busy schedule impeded radio’s success—one could now perform an activity and listen to the radio at the same time. This unprecedented reach made radio an instrument of social cohesion as it brought together members of different classes and backgrounds to experience the world as a nation.

Radio programs reflected this nationwide cultural aspect of radio. Vox Pop, a show originally based on person-in-the-street interviews, was an early attempt to quantify the United States’ growing mass culture. Beginning in 1935, the program billed itself as an unrehearsed “cross-section of what the average person really knows” by asking random people an assortment of questions. Many modern television shows still employ this format not only for viewers’ amusement and information but also as an attempt to sum up national culture (Loviglio, 2002). Vox Pop functioned on a cultural level as an acknowledgement of radio’s entrance into people’s private lives to make them public (Loviglio, 2002).

Radio news was more than just a quick way to find out about events; it was a way for U.S. citizens to experience events with the same emotions. During the Ohio and Mississippi river floods of 1937, radio brought the voices of those who suffered as well as the voices of those who fought the rising tides. A West Virginia newspaper explained the strengths of radio in providing emotional voices during such crises: “Thanks to radio…the nation as a whole has had its nerves, its heart, its soul exposed to the needs of its unfortunates…We are a nation integrated and interdependent. We are ‘our brother’s keeper (Brown).’”

Radio’s presence in the home also heralded the evolution of consumer culture in the United States. In 1941, two-thirds of radio programs carried advertising. Radio allowed advertisers to sell products to a captive audience. This kind of mass marketing ushered in a new age of consumer culture (Cashman).

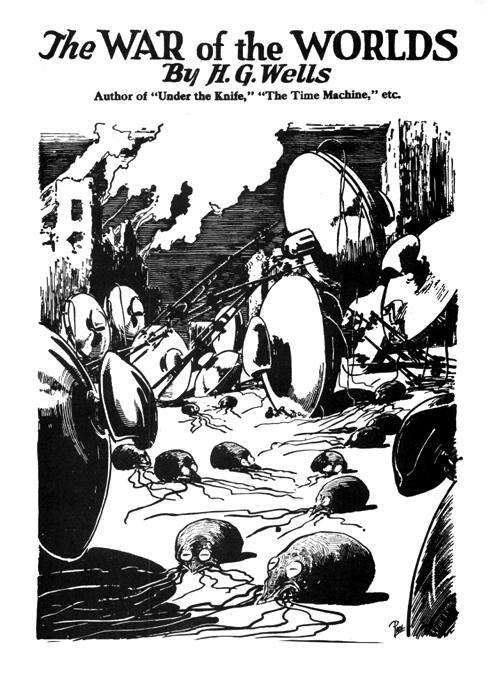

War of the Worlds and the Power of Radio

During the 1930s, radio’s impact and powerful social influence was perhaps most obvious in the aftermath of the Orson Welles’s notorious War of the Worlds broadcast. On Halloween night in 1938, radio producer Orson Welles told listeners of the Mercury Theatre on the Air that they would be treated to an original adaptation of H. G. Wells’s classic science fiction novel of alien invasion War of the Worlds. The adaptation started as if it were a normal music show that was interrupted by news reports of an alien invasion. Many listeners had tuned in late and did not hear the disclaimer, and so were caught up by the realism of the adaptation, believing it to be an actual news story.

Figure 7.5

Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds broadcast terrified listeners, many of whom actually believed a Martian invasion was actually occurring.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

According to some, an estimated 6 million people listened to the show, with an incredible 1.7 million believing it to be true (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). Some listeners called loved ones to say goodbye or ran into the street armed with weapons to fight off the invading Martians of the radio play (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). In Grovers Mill, New Jersey—where the supposed invasion began—some listeners reported nonexistent fires and fired gunshots at a water tower thought to be a Martian landing craft. One listener drove through his own garage door in a rush to escape the area. Two Princeton University professors spent the night searching for the meteorite that had supposedly preceded the invasion (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). As calls came in to local police stations, officers explained that they were equally concerned about the problem (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005).

Although the story of the War of the Worlds broadcast may be funny in retrospect, the event traumatized those who believed the story. Individuals from every education level and walk of life had been taken in by the program, despite the producers’ warnings before, during the intermission, and after the program (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). This event revealed the unquestioning faith that many Americans had in radio. Radio’s intimate communication style was a powerful force during the 1930s and 1940s.

Radio and the Development of Popular Music

One of radio’s most enduring legacies is its impact on music. Before radio, most popular songs were distributed through piano sheet music and word of mouth. This necessarily limited the types of music that could gain national prominence. Although recording technology had also emerged several decades before radio, music played live over the radio sounded better than it did on a record played in the home. Live music performances thus became a staple of early radio. Many performance venues had their own radio transmitters to broadcast live shows—for example, Harlem’s Cotton Club broadcast performances that CBS picked up and broadcast nationwide.

Radio networks mainly played swing jazz, giving the bands and their leaders a widespread audience. Popular bandleaders including Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey and their jazz bands became nationally famous through their radio performances, and a host of other jazz musicians flourished as radio made the genre nationally popular (Wald, 2009). National networks also played classical music. Often presented in an educational context, this programming had a different tenor than did dance-band programming. NBC promoted the genre through shows such as the Music Appreciation Hour, which sought to educate both young people and the general public on the nuances of classical music (Howe, 2003). It created the NBC Symphony Orchestra, a 92-piece band under the direction of famed conductor Arturo Toscanini. The orchestra made its first performance in 1937 and was so popular that Toscanini stayed on as conductor for 17 years (Horowitz, 2005). The Metropolitan Opera was also popular; its broadcasts in the early 1930s had an audience of 9 million listeners (Horowitz, 2005).

Regional Sounds Take Hold

The promotional power of radio also gave regional music an immense boost. Local stations often carried their own programs featuring the popular music of the area. Stations such as Nashville, Tennessee’s WSM played early country, blues, and folk artists. The history of this station illustrates the ways in which radio—and its wide range of broadcasting—created new perspectives on American culture. In 1927, WSM’s program Barn Dance, which featured early country music and blues, followed an hour-long program of classical music. George Hay, the host of Barn Dance, used the juxtaposition of classical and country genres to spontaneously rename the show: “For the past hour we have been listening to music taken largely from Grand Opera, but from now on we will present ‘The Grand Ole Opry (Kyriakoudes).’” NBC picked up the program for national syndication in 1939, and it is currently one of the longest-running radio programs of all time.

Figure 7.6

The Grand Ole Opry gave a national stage to country and early rock musicians.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Shreveport, Louisiana’s KWKH aired an Opry-type show called Louisiana Hayride. This program propelled stars such as Hank Williams into the national spotlight. Country music, formerly a mix of folk, blues, and mountain music, was made into a genre that was accessible by the nation through this show. Without programs that featured these country and blues artists, Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash would not have become national stars, and country music may not have risen to become a popular genre (DiMeo, 2010).

In the 1940s, other Southern stations also began playing rhythm and blues records recorded by Black artists. Artists such as Wynonie Harris, famous for his rendition of Roy Brown’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” were often played by White disc jockeys who tried to imitate Black Southerners (Laird, 2005). During the late 1940s, both Memphis, Tennessee’s WDIA and Atlanta, Georgia’s WERD were owned and operated by Black individuals. These disc jockeys often provided a measure of community leadership at a time when few Black individuals were in powerful positions (Walker).

Radio’s Lasting Influences

Radio technology changed the way that dance and popular music were performed. Because of the use of microphones, vocalists could be heard better over the band, allowing singers to use a greater vocal range and create more expressive styles, an innovation that led singers to become an important part of popular music’s image. The use of microphones similarly allowed individual performers to be featured playing solos and lead parts, features that were less encouraged before radio. The exposure of radio also led to more rapid turnover in popular music. Before radio, jazz bands played the same arrangement for several years without it getting old, but as radio broadcasts reached wide audiences, new arrangements and songs had to be produced at a more rapid pace to keep up with changing tastes (Wald).

The spotlight of radio allowed the personalities of artists to come to the forefront of popular music, giving them newfound notoriety. Phil Harris, the bandleader from the Jack Benny Show, became the star of his own program. Other famous musicians used radio talent shows to gain fame. Popular programs such as Major Bowes and His Original Amateur Hour featured unknown entertainers trying to gain fame through exposure to the show’s large audience. Major Bowes used a gong to usher bad performers offstage, often contemptuously dismissing them, but not all the performers struck out; such successful singers as Frank Sinatra debuted on the program (Sterling & Kitross).

Television, much like modern popular music, owes a significant debt to the Golden Age of Radio. Major radio networks such as NBC, ABC, and CBS became—and remain—major forces in television, and their programming decisions for radio formed the basis for television. Actors, writers, and directors who worked in radio simply transferred their talents into the world of early television, using the successes of radio as their models.

Radio and Politics

Over the years, radio has had a considerable influence on the political landscape of the United States. In the past, government leaders relied on radio to convey messages to the public, such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “fireside chats.” Radio was also used as a way to generate propaganda for World War II. The War Department established a Radio Division in its Bureau of Public Relations as early as 1941. Programs such as the Treasury Hour used radio drama to raise revenue through the sale of war bonds, but other government efforts took a decidedly political turn. Norman Corwin’s This Is War! was funded by the federal Office of Facts and Figures (OFF) to directly garner support for the war effort. It featured programs that prepared listeners to make personal sacrifices—including death—to win the war. The program was also directly political, popularizing the idea that the New Deal was a success and bolstering Roosevelt’s image through comparisons with Lincoln (Horten).

FDR’s Fireside Chats

Figure 7.7

During his presidency, Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered fireside chats, a series of radio broadcasts in which he spoke directly to the American people.

UNC Greensboro Special Collections and University Archives – Franklin Roosevelt photograph, 1940s – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-era radio talks, or “fireside chats,” remain one of the most famous uses of radio in politics. While governor of New York, Roosevelt had used radio as a political tool, so he quickly adopted it to explain the unprecedented actions that his administration was taking to deal with the economic fallout of the Great Depression. His first speech took place only 1 week after being inaugurated. Roosevelt had closed all of the banks in the country for 4 days while the government dealt with a national banking crisis, and he used the radio to explain his actions directly to the American people (Grafton, 1999).

Roosevelt’s first radio address set a distinct tone as he employed informal speech in the hopes of inspiring confidence in the American people and of helping them stave off the kind of panic that could have destroyed the entire banking system. Roosevelt understood both the intimacy of radio and its powerful outreach (Grafton, 1999). He was thus able to balance a personal tone with a message that was meant for millions of people. This relaxed approach inspired a CBS executive to name the series the “fireside chats (Grafton, 1999).”

Roosevelt delivered a total of 27 of these 15- to 30-minute-long addresses to estimated audiences of 30 million to 40 million people, then a quarter of the U.S. population (Grafton, 1999). Roosevelt’s use of radio was both a testament to his own skills and savvy as a politician and to the power and ubiquity of radio during this period. At the time, there was no other form of mass media that could have had the same effect.

Certainly, radio has been used by the government for its own purposes, but it has had an even greater impact on politics by serving as what has been called “the ultimate arena for free speech (Davis & Owen, 1998).” Such infamous radio firebrands as Father Charles Coughlin, a Roman Catholic priest whose radio program opposed the New Deal, criticized Jews, and supported Nazi policies, aptly demonstrated this capability early in radio’s history (Sterling & Kitross). In recent decades, radio has supported political careers, including those of U.S. Senator Al Franken of Minnesota, former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, and presidential aspirant Fred Thompson. Talk show hosts such as Rush Limbaugh have gained great political influence, with some even viewing Limbaugh as the de facto leader of the Republican Party (Halloran, 2009).

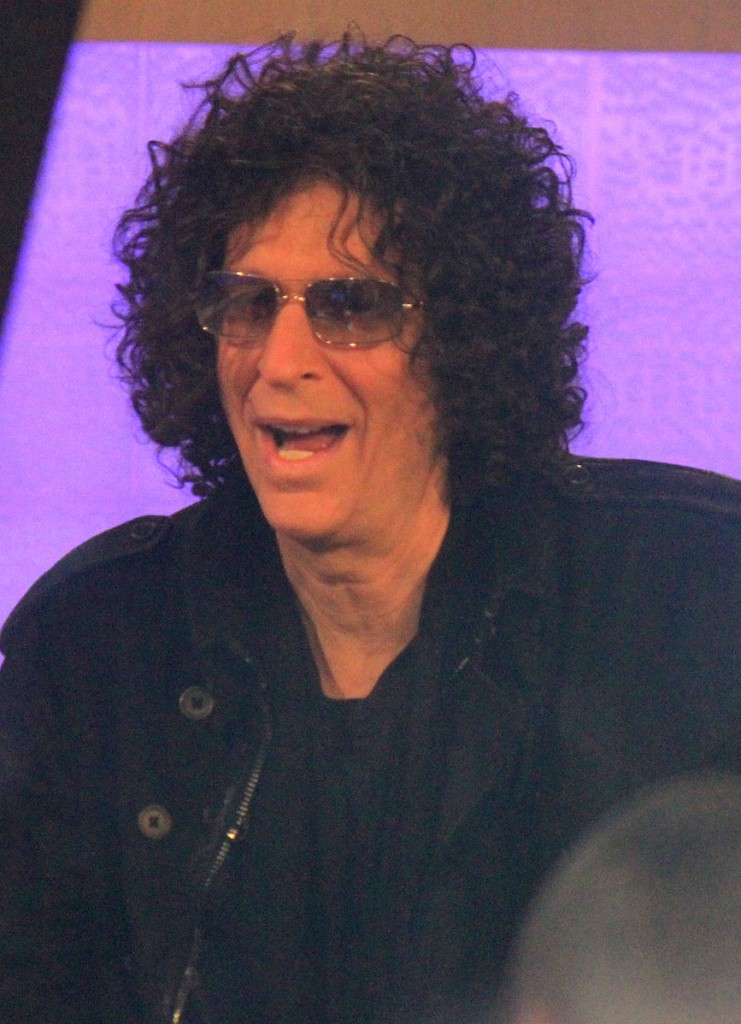

The Importance of Talk Radio

An important contemporary convergence of radio and politics can be readily heard on modern talk radio programs. Far from being simply chat shows, the talk radio that became popular in the 1980s features a host who takes callers and discusses a wide assortment of topics. Talk radio hosts gain and keep their listeners by sheer force of personality, and some say shocking or insulting things to get their message across. These hosts range from conservative radio hosts such as Rush Limbaugh to so-called shock jocks such as Howard Stern.

Repeal of the Fairness Doctrine

While talk radio first began during the 1920s, the emergence of the format as a contemporary cultural and political force took place during the mid- to late-1980s following the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine (Cruz, 2007). As you read earlier in this chapter, this doctrine, established in 1949, required any station broadcasting a political point of view over the air to allow equal time to all reasonable dissenting views. Despite its noble intentions of safeguarding public airwaves for diverse views, the doctrine had long attracted a level of dissent. Opponents of the Fairness Doctrine claimed that it had a chilling effect on political discourse as stations, rather than risk government intervention, avoided programs that were divisive or controversial (Cruz, 2007). In 1987, the FCC under the Reagan administration repealed the regulation, setting the stage for an AM talk radio boom; by 2004, the number of talk radio stations had increased by 17-fold (Anderson, 2005).

The end of the Fairness Doctrine allowed stations to broadcast programs without worrying about finding an opposing point of view to balance the stated opinions of its host. Radio hosts representing all points of the political spectrum could say anything that they wanted to—within FCC limits—without fear of rebuttal. Media bias and its ramifications will be explored at greater length in Chapter 14 “Ethics of Mass Media”.

The Revitalization of AM

The migration of music stations to the FM spectrum during the 1960s and 1970s provided a great deal of space on the AM band for talk shows. With the Fairness Doctrine no longer a hindrance, these programs slowly gained notoriety during the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1998, talk radio hosts railed against a proposed congressional pay increase, and their listeners became incensed; House Speaker Jim Wright received a deluge of faxes protesting it from irate talk radio listeners from stations all over the country (Douglas). Ultimately, Congress canceled the pay increase, and various print outlets acknowledged the influence of talk radio on the decision. Propelled by events such as these, talk radio stations rose from only 200 in the early 1980s to more than 850 in 1994 (Douglas).

Coast to Coast AM

Although political programs unquestionably rule AM talk radio, that dial is also home to a kind of show that some radio listeners may have never experienced. Late at night on AM radio, a program airs during which listeners hear stories about ghosts, alien abductions, and fantastic creatures. It’s not a fictional drama program, however, but instead a call-in talk show called Coast to Coast AM. In 2006, this unlikely success ranked among the top 10 AM talk radio programs in the nation—a stunning feat considering its 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. time slot and bizarre format (Vigil, 2006).

Originally started by host Art Bell in the 1980s, Coast to Coast focuses on topics that mainstream media outlets rarely treat seriously. Regular guests include ghost investigators, psychics, Bigfoot biographers, alien abductees, and deniers of the moon landing. The guests take calls from listeners who are allowed to ask questions or talk about their own paranormal experiences or theories.

Coast to Coast’s current host, George Noory, has continued the show’s format. In some areas, its ratings have even exceeded those of Rush Limbaugh’s (Vigil, 2006). For a late-night show, these kinds of high ratings are rare. The success of Coast to Coast is thus a continuing testament to the diversity and unexpected potential of radio (Vigil, 2006).

On-Air Political Influence

As talk radio’s popularity grew during the early 1990s, it quickly became an outlet for political ambitions. In 1992, nine talk show hosts ran for U.S. Congress. By the middle of the decade, it had become common for many former—or failed—politicians to attempt to use the format. Former California governor Jerry Brown and former New York mayor Ed Koch were among the mid-1990s politicians that had AM talk shows (Annenberg Public Policy Center, 1996). Both conservatives and liberals widely agree that conservative hosts dominate AM talk radio. Many talk show hosts, such as Limbaugh, who began his popular program 1 year after the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine, have made a profitable business out of their programs.

Figure 7.8

Talk radio shows increased dramatically in number and popularity in the wake of the 1987 repeal of the Fairness Doctrine.

JD Lasica – Blogworld Talk Radio – CC BY-NC 2.0.

During the 2000s, AM talk radio continued to build. Hosts such as Michael Savage, Sean Hannity, and Bill O’Reilly furthered the trend of popular conservative talk shows, but liberal hosts also became popular through the short-lived Air America network. The network closed abruptly in 2010 amid financial concerns (Stelter, 2010). Although the network was unsuccessful, it provided a platform for such hosts as MSNBC TV news host Rachel Maddow and Minnesota Senator Al Franken. Other liberal hosts such as Bill Press and Ron Reagan, son of President Ronald Reagan, have also found success in the AM political talk radio field (Stelter, 2010). Despite these successes, liberal talk radio is often viewed as unsustainable (Hallowell, 2010). To some, the failure of Air America confirms conservatives’ domination of AM radio. In response to the conservative dominance of talk radio, many prominent liberals, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, have advocated reinstating the Fairness Doctrine and forcing stations to offer equal time to contrasting opinions (Stotts, 2008).

Freedom of Speech and Radio Controversies

While the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution gives radio personalities the freedom to say nearly anything they want on the air without fear of prosecution (except in cases of obscenity, slander, or incitement of violence, which will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 15 “Media and Government”), it does not protect them from being fired from their jobs when their controversial comments create a public outrage. Many talk radio hosts, such as Howard Stern, push the boundaries of acceptable speech to engage listeners and boost ratings, but sometimes radio hosts push too far, unleashing a storm of controversy.

Making (and Unmaking) a Career out of Controversy

Talk radio host Howard Stern has managed to build his career on creating controversy—despite being fined multiple times for indecency by the FCC, Stern remains one of highest-paid and most popular talk radio hosts in the United States. Stern’s radio broadcasts often feature scatological or sexual humor, creating an “anything goes” atmosphere. Because his on-air antics frequently generate controversy that can jeopardize advertising sponsorships and drive away offended listeners—in addition to risking fines from the FCC—Stern has a history of uneasy relationships with the radio stations that employ him. In an effort to free himself of conflicts with station owners and sponsors, in 2005 Stern signed a contract with Sirius Satellite Radio, which is exempt from FCC regulation, so that he can continue to broadcast his show without fear of censorship.

Stern’s massive popularity gives him a lot of clout, which has allowed him to weather controversy and continue to have a successful career. Other radio hosts who have gotten themselves in trouble with poorly considered on-air comments have not been so lucky. In April 2007, Don Imus, host of the long-running Imus in the Morning, was suspended for racist and sexist comments made about the Rutgers University women’s basketball team (MSNBC, 2007). Though he publically apologized, the scandal continued to draw negative attention in the media, and CBS canceled his show to avoid further unfavorable publicity and the withdrawal of advertisers. Though he returned to the airwaves in December of that year with a different station, the episode was a major setback for Imus’s career and his public image. Similarly, syndicated conservative talk show host Dr. Laura Schelssinger ended her radio show in 2010 due to pressure from radio stations and sponsors after her repeated use of a racial epithet on a broadcast incited a public backlash (MSNBC, 2007).

As the examples of these talk radio hosts show, the issue of freedom of speech on the airwaves is often complicated by the need for radio stations to be profitable. Outspoken or shocking radio hosts can draw in many listeners, attracting advertisers to sponsor their shows and bringing in money for their radio stations. Although some listeners may be offended by these hosts and may stop tuning in, as long as the hosts continue to attract advertising dollars, their employers are usually content to allow the hosts to speak freely on the air. However, if a host’s behavior ends up sparking a major controversy, causing advertisers to withdraw their sponsorship to avoid tarnishing their brands, the radio station will often fire the host and look to someone who can better sustain advertising partnerships. Radio hosts’ right to free speech does not compel their employer to give them the forum to exercise it. Popular hosts like Don Imus may find a home on the air again once the furor has died down, but for radio hosts concerned about the stability of their careers, the lesson is clear: there are practical limits on their freedom of speech.

Key Takeaways

- Radio was unique as a form of mass media because it had the potential to reach anyone, even the illiterate. Radio news in the 1930s and 1940s brought the emotional impact of traumatic events home to the listening public in a way that gave the nation a sense of unity.

- Radio encouraged the growth of national popular music stars and brought regional sounds to wider audiences. The effects of early radio programs can be felt both in modern popular music and in television programming.

- The Fairness Doctrine was created to ensure fair coverage of issues over the airwaves. It stated that radio stations must give equal time to contrasting points of view on an issue. An enormous rise in the popularity of AM talk radio occurred after the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine in 1987.

- The need for radio stations to generate revenue places practical limits on what radio personalities can say on the air. Shock jocks like Howard Stern and Don Imus test, and sometimes exceed, these limits and become controversial figures, highlighting the tension between freedom of speech and the need for businesses to be profitable.

Exercises

Please respond to the following writing prompts. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- Describe the unique qualities that set radio apart from other forms of mass media, such as newspapers.

- How did radio bring new music to places that had never heard it before?

- Describe political talk radio before and after the Fairness Doctrine. What kind of effect did the Fairness Doctrine have?

- Do you think that the Fairness Doctrine should be reinstated? Explain your answer.

- Investigate the controversy surrounding Don Imus and the comments that led to his show’s cancellation. What is your opinion of his comments and CBS’s reaction to them?

References

Anderson, Brian. South Park Conservatives: The Revolt Against Liberal Media Bias (Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2005), 35–36.

Annenberg Public Policy Center, Call-In Political Talk Radio: Background, Content, Audiences, Portrayal in Mainstream Media, Annenberg Public Policy Center Report Series, August 7, 1996, http://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/Downloads/Political_Communication/Political_Talk_Radio

/1996_03_political_talk_radio_rpt.PDF.

Brown, Manipulating the Ether, 140.

Cashman, America in the Twenties and Thirties, 329.

Cruz, Gilbert. “GOP Rallies Behind Talk Radio,” Time, June 28, 2007, http://www.time.com/time/politics/article/0,8599,1638662,00.html.

Davis, Richard. and Diana Owen, New Media and American Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 54.

DiMeo, Nate. “New York Clashes with the Heartland,” Hearing America: A Century of Music on the Radio, American Public Media, 2010, http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/radio/b1.html.

Douglas, Listening In, 287.

Grafton, John. ed., Great Speeches—Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Mineola, NY: Dover, 1999), 34.

Halloran, Liz. “Steele-Limbaugh Spat: A Battle for GOP’s Future?” NPR, March 2, 2009, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=101430572.

Hallowell, Billy. “Media Matters’ Vapid Response to Air America’s Crash,” Big Journalism, January 26, 2010, http://bigjournalism.com/bhallowell/2010/01/26/media-matters-vapid-response-to-air-americas-crash.

Horowitz, Joseph. Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall (New York: Norton, 2005), 399–404.

Horten, Radio Goes to War, 45–47.

Howe, Sondra Wieland “The NBC Music Appreciation Hour: Radio Broadcasts of Walter Damrosch, 1928–1942,” Journal of Research in Music Education 51, no. 1 (Spring 2003).

Kyriakoudes, Louis. The Social Origins of the Urban South: Race, Gender, and Migration in Nashville and Middle Tennessee, 1890–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 7.

Laird, Tracey. Louisiana Hayride: Radio and Roots Music Along the Red River (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 4–10.

Loviglio, Jason. “Vox Pop: Network Radio and the Voice of the People” in Radio Reader: Essays in the Cultural History of Radio, ed. Michele Hilmes and Jason Loviglio (New York: Routledge, 2002), 89–106.

Lubertozzi, Alex and Brian Holmsten, The War of the Worlds: Mars’ Invasion of Earth, Inciting Panic and Inspiring Terror From H. G. Wells to Orson Welles and Beyond (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2005), 7–9.

MSNBC, Imus in the Morning, MSNBC, April 4, 2007.

Stelter, Brian. “Liberal Radio, Even Without Air America,” New York Times, January 24, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/25/arts/25radio.html.

Sterling and Kitross, Stay Tuned, 182.

Sterling and Kitross, Stay Tuned, 199.

Stotts, Bethany. “Pelosi Supports Return of Fairness Doctrine,” Accuracy in Media Column, June 26, 2008, http://www.aim.org/aim-column/pelosi-support-return-of-fairness-doctrine.

Vigil, Delfin. “Conspiracy Theories Propel AM Radio Show Into the Top Ten,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 12, 2006, http://articles.sfgate.com/2006-11-12/news/17318973_1_radio-show-coast-cold-war.

Wald, Beatles Destroyed Rock ’n’ Roll, 95–96.

Wald, Elijah. How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ’n’ Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 100–104.

Walker, Rebels on the Air, 53–54.

7.5 Radio’s New Future

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish the differences between satellite radio, HD radio, Internet radio, and podcasting.

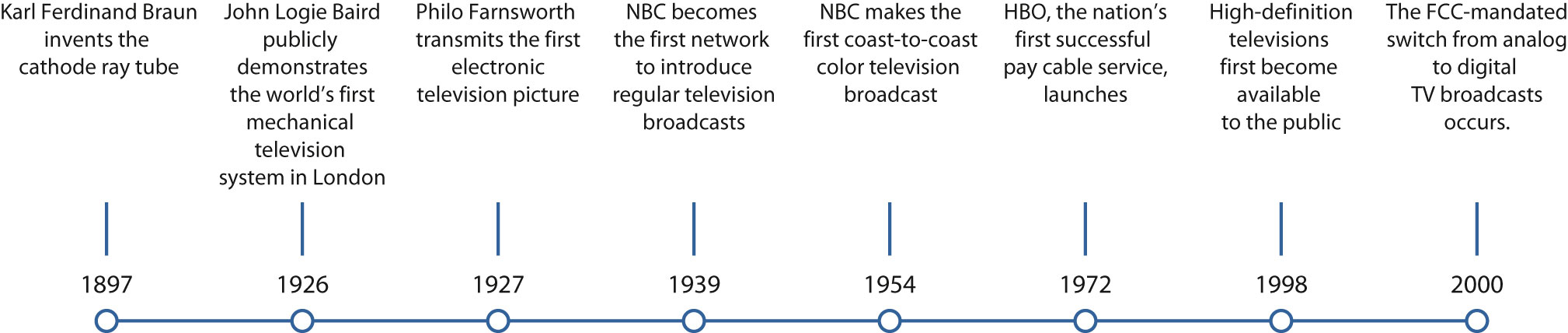

- Identify the development of new radio technologies.