1.3 The Evolution of Media

Today, Americans can turn on a television and easily find 24-hour news channels, music videos, nature documentaries, and reality shows about everything from hoarders to fashion designers. That’s not to mention movies provided on demand by cable companies or television, as well as video available online for streaming or downloading. Print media has struggled to adapt; in 2022, U.S. daily newspaper circulation was 20.9 million, down from 60.7 million in 1991 at the start of the information age (Pew Research Center, 2024). A University of California, San Diego study claimed that U.S. households consumed approximately 3.6 zettabytes of information in 2008—the digital equivalent of a 7-foot-high stack of books covering the entire United States—a 350 percent increase since 1980 (Ramsey, 2009). According to data from the Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association, annual mobile wireless data consumption in the United States grew almost 140-fold between 2010 and 2021, resulting in 53.4 trillion megabytes of data traffic in the latter year (CTIA, 2022). Americans expose themselves to media in various settings, including taxicabs, buses, classrooms, doctors’ offices, highways, and airplanes. Individuals can begin to orient themselves in the information cloud by examining the roles the media plays in society, its history within this society, and how technological innovations have helped shape the modern world.

What Does Media Do for Us?

The media fulfills several fundamental roles in society. One prominent role is entertainment. Media can act as a springboard for human imagination, a source of fantasy, and an outlet for escapism. In the 19th century, Victorian readers disillusioned by the grimness of the Industrial Revolution found themselves drawn into fantastic worlds of fairies and other fictitious beings. In the first decade of the 21st century, American television viewers and streamers could watch a young genius come to age in Young Sheldon; witness political machinations and brutal betrayal in Game of Thrones; follow an inexperienced American attempt to coach an English football team in Ted Lasso; or watch humanity attempt to repopulate the world through repressed sexual slavery in The Handmaid’s Tale. By providing its audiences with a wide range of stories, the media has the power to let people escape the problems and monotony of everyday life.

Media can also provide information and education. Information can come in many forms, and it may sometimes be difficult to separate from entertainment. Today, news organizations utilize mass communication platforms to transmit stories from across the globe, enabling readers or viewers in London to access voices and videos from Baghdad, Tokyo, or Buenos Aires. Books and magazines offer in-depth examinations of a wide range of subjects. The free online encyclopedia Wikipedia features articles on a wide range of topics, from presidential nicknames to child prodigies and tongue twisters in various languages. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has posted free lecture notes, exams, and audio and video recordings of classes on its OpenCourseWare website, allowing anyone with an Internet connection access to world-class professors and instruction.

Another valuable aspect of media is its ability to serve as a public forum for discussing important issues. Newspapers and other periodicals publish letters to the editor to allow readers to respond to journalists or to voice their opinions on the day’s issues. These letters were an essential part of U.S. newspapers even when the nation was a British colony, and they have served as a means of public discourse ever since. The Internet is a fundamentally democratic medium that allows everyone with online access to express their opinions on various digital platforms. Whether anyone will ever hear or read the content remains another question.

Similarly, people can use media to monitor the government, businesses, and other institutions. More than a century ago, Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle exposed the miserable conditions in the turn-of-the-century meatpacking industry. In the early 1970s, Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered evidence of the Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up, which eventually led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. However, purveyors of mass media may be beholden to particular agendas due to political slants, advertising funds, or ideological biases, thus constraining their ability to act as a watchdog. The following list outlines some of the agendas of the media:

- Entertaining and providing an outlet for the imagination

- Educating and informing

- Serving as a public forum for the discussion of important issues

- Acting as a watchdog for government, business, and other institutions

It’s important to remember that not all media are created equal. While some forms of mass communication are better suited for entertainment, others are more suitable as a venue for spreading information. In terms of print media, books possess durability and can contain a lot of information, but are relatively slow and expensive to produce. In contrast, newspapers are comparatively cheaper and quicker to create, making them a better medium for the quick turnover of daily news. Television allows the presentation of visual information that radio cannot, and presents information more dynamically than a static printed page. It can also be used to broadcast live events to a nationwide audience, as in the annual State of the Union address given by the U.S. president. However, it is also a one-way medium; it permits very little direct person-to-person communication. In contrast, the Internet encourages public discussion of issues and allows nearly everyone who wants a voice to have one. However, the Internet is also largely unmoderated. Users may have to wade through thousands of inane comments or misinformed amateur opinions to find quality information.

The 1960s media theorist Marshall McLuhan took these ideas one step further, famously coining the phrase “the medium is the message (McLuhan, 1964).” By this, McLuhan meant that every medium has a profound impact on how the audience interprets the message. McLuhan said that each medium can present the same information differently, and that the content and how it is presented are fundamentally shaped by the medium of transmission.

For example, television news has the advantage of offering video and live coverage. This helps connect the audience to the story and makes it come alive more vividly, resulting in a faster-paced delivery of information. That means more stories get covered in less depth since extraneous details can bog the story down. A story told on television will probably be flashier, less in-depth, and with less context than the same story covered in a monthly magazine since print publications most overcome space constraints, not time; therefore, people who get the majority of their news from television may have a particular view of the world shaped not by the content of what they watch but its medium.

Computer scientist Alan Kay said, “Each medium has a special way of representing ideas that emphasize particular ways of thinking and de-emphasize others (Kay, 1994).” Kay wrote this in 1994 as the Internet transitioned from an academic research network to a publicly accessible system. However, McLuhan’s claims leave little room for individual autonomy or resistance. In an essay about television’s effects on contemporary fiction, writer David Foster Wallace scoffed at the “reactionaries who regard TV as some malignancy visited on an innocent populace, sapping IQs and compromising SAT scores while we all sit there on ever fatter bottoms with little mesmerized spirals revolving in our eyes…. Treating television as evil is just as reductive and silly as treating it like a toaster with pictures (Wallace, 1997).” Nonetheless, media messages and technologies affect people in countless ways, both obvious and subtle.

A Brief History of Mass Media and Culture

Until Johannes Gutenberg’s 15th-century invention of the movable-type printing press, books were painstakingly handwritten, and no two copies were identical. The printing press enabled the mass production of print media. Not only did it reduce the cost of producing written material, but new transportation technologies also made it easier for texts to reach a broad audience. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Gutenberg’s invention, which helped usher in massive cultural movements, such as the European Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. In 1810, another German printer, Friedrich Koenig, further advanced media production by essentially linking the steam engine to a printing press, thereby enabling the industrialization of printed media. In 1800, a hand-operated printing press could produce about 480 pages per hour; Koenig’s machine more than doubled this rate. By the 1930s, printing presses could publish 3,000 pages an hour.

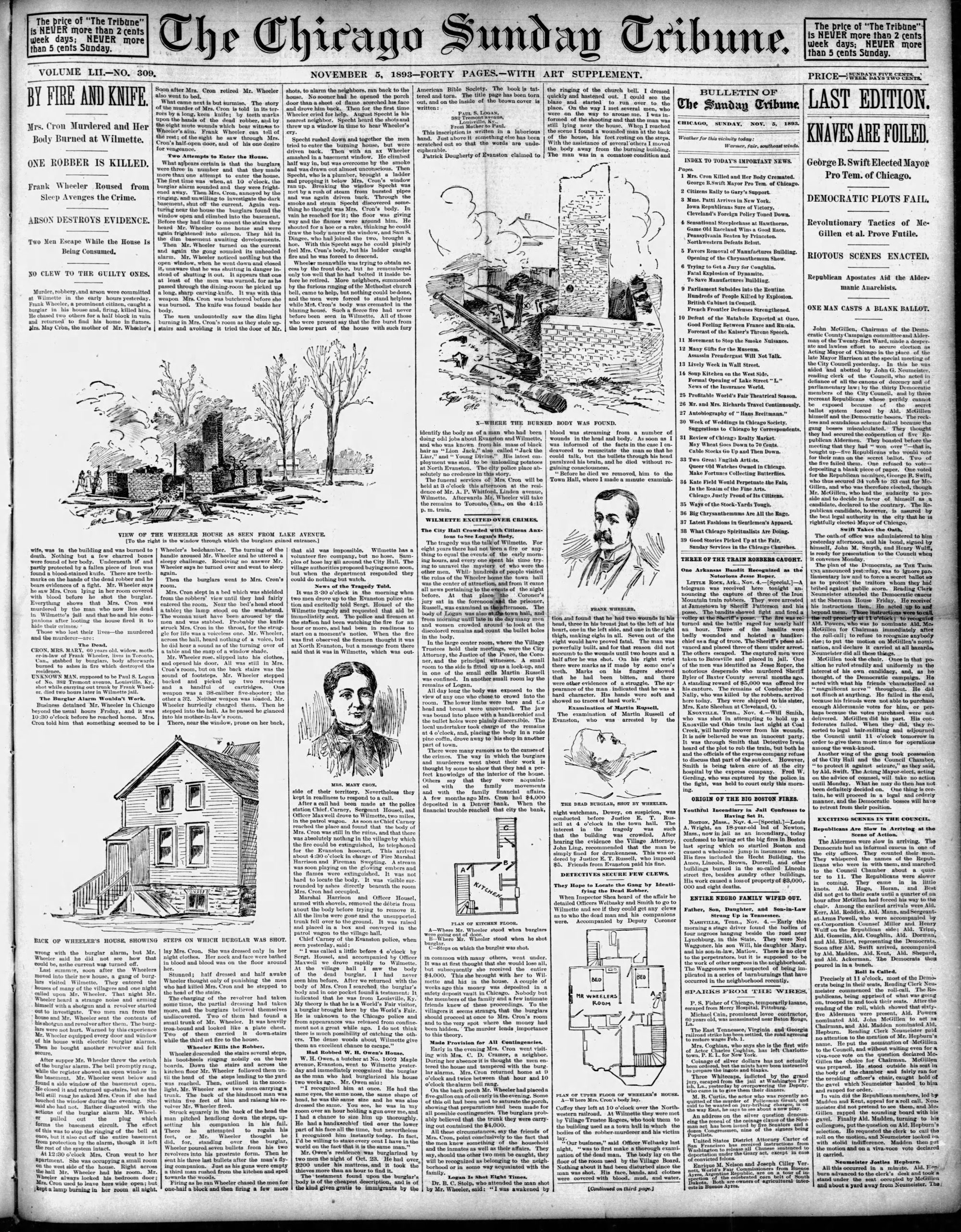

This increased efficiency went hand in hand with the rise of the daily newspaper. The newspaper was the perfect medium for the increasingly urbanized Americans of the 19th century, who could no longer get their local news merely through gossip and word of mouth. These Americans lived in unfamiliar territory, and newspapers and other media helped them negotiate the rapidly changing world. The Industrial Revolution meant that some people had more leisure time and money, and the press helped them figure out how to spend both. Media theorist Benedict Anderson has argued that newspapers also helped forge a sense of national identity by treating readers across the country as part of one unified community (Anderson, 1991).

In the 1830s, the major daily newspapers faced a new threat from the rise of penny papers, which were low-priced broadsheets that provided a cheaper and more sensational daily news source. They favored news of murder and adventure over the dry political news of the day. While newspapers catered to a wealthier, more educated audience, the penny press aimed to reach a broad range of readers through affordable prices and entertaining (often scandalous) stories. The penny press can be seen as the forerunner to today’s gossip-hungry tabloids.

In the early 20th century, the first primary non-print form of mass media—radio—exploded in popularity. Radios, which were less expensive than telephones and widely available by the 1920s, had the unprecedented ability to allow vast numbers of people to listen to the same event in real time as it occurred. In 1924, Calvin Coolidge’s pre-election speech reached more than 20 million people. Advertisers loved radio due to its access to a large and captive audience. An early advertising consultant claimed that the early days of radio were “a glorious opportunity for the advertising man to spread his sales propaganda” because of “a countless audience, sympathetic, pleasure-seeking, enthusiastic, curious, interested, approachable in the privacy of their homes (Briggs & Burke, 2005).” The reach of radio also meant that the medium could downplay regional differences and foster a unified sense of the American lifestyle, which had become increasingly defined by consumer purchases. “Americans in the 1920s were the first to wear ready-made, exact-size clothing…to play electric phonographs, to use electric vacuum cleaners, to listen to commercial radio broadcasts, and to drink fresh orange juice year-round (Mintz, 2007).” This boom in consumerism left its mark on the 1920s and contributed to the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s (Library of Congress). The consumerist impulse drove production to unprecedented levels. Still, when the Depression began, and consumer demand dropped dramatically, the surplus of production helped further deepen the economic crisis as more goods were being produced than could be sold.

The post–World War II era in the United States was marked by prosperity and the introduction of a seductive new form of mass communication: television. In 1946, about 17,000 televisions existed in the United States; within seven years, two-thirds of American households owned at least one set. As the United States’ gross national product (GNP) doubled in the 1950s, and again in the 1960s, the American home became firmly ensconced as a consumer unit; along with a television, the typical U.S. household owned a car and a house in the suburbs, all of which contributed to the nation’s thriving consumer-based economy (Briggs & Burke, 2005). Broadcast television was the dominant form of mass media, and the three major networks —NBC, CBS, and ABC —controlled more than 90 percent of the news programs, live events, and sitcoms viewed by Americans. Social critics argue that television has fostered a homogeneous, conformist culture by reinforcing ideas about what constitutes the “normal” American experience. But television also contributed to the counterculture of the 1960s. The Vietnam War was the nation’s first televised military conflict, and nightly images of war footage and war protesters helped intensify the nation’s internal conflicts.

Broadcast technology, including radio and television, had such a profound impact on the American imagination that newspapers and other print media had to adapt to the new media landscape to survive economically, as their traditional methods of delivering messages to a mass audience were now competing with new alternatives. Print media was more durable and easier to archive. It allowed users more flexibility in terms of time—once a person had purchased a magazine, they could read it whenever and wherever. Broadcast media, in contrast, usually aired programs on a fixed schedule, which allowed them to both provide a sense of immediacy and fleetingness. Until the advent of digital video recorders in the late 1990s, it was impossible to pause and rewind a live television broadcast.

The media world underwent drastic changes once again in the 1980s and 1990s with the widespread adoption of cable television. During the early decades of television, viewers had a limited number of channels to choose from—one reason for the charges of homogeneity. In 1975, the three major networks accounted for 93 percent of all television viewing. By 2004, however, this share had dropped to 28.4 percent of total viewing, mainly due to the widespread adoption of cable television programming. Cable providers offered viewers a wide range of choices, including channels tailored explicitly to those who wanted to watch only golf, classic films, sermons, shark videos, and more. Still, until the mid-1990s, the three large national networks dominated the television landscape. The Telecommunications Act of 1996, an attempt to foster competition by deregulating the industry, actually resulted in many mergers and buyouts that left most of the control of the broadcast spectrum in the hands of a few large corporations. In 2003, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) further loosened regulations, allowing a single company to own up to 45 percent of a single market (up from 25 percent in 1982). In 2017, the agency rolled back rules that had previously prevented ownership of a newspaper and a broadcast station in the same market (Kemp 2015). Four years later, the Supreme Court ruled that the FCC had not violated the Constitution when it loosened restrictions on the ownership of radio stations, television stations, and newspapers.

New media technologies both spring from and cause social changes. For this reason, it can be irresponsible to neatly sort the evolution of media into clear causes and effects. Did radio fuel the consumerist boom of the 1920s, or did it become wildly popular because it appealed to a society that had already begun exploring consumerist tendencies? A little bit of both. Technological innovations such as the steam engine, electricity, wireless communication, and the Internet have all had lasting and significant effects on American culture. As media historians Asa Briggs and Peter Burke note, every crucial invention came with “a change in historical perspectives” (Briggs & Burke, 2005). Electricity altered the way people thought about time. Work and play no longer depended on the daily rhythms of sunrise and sunset. Since then, wireless communication has collapsed distance, while the Internet revolutionized the way humanity stores and retrieves information.

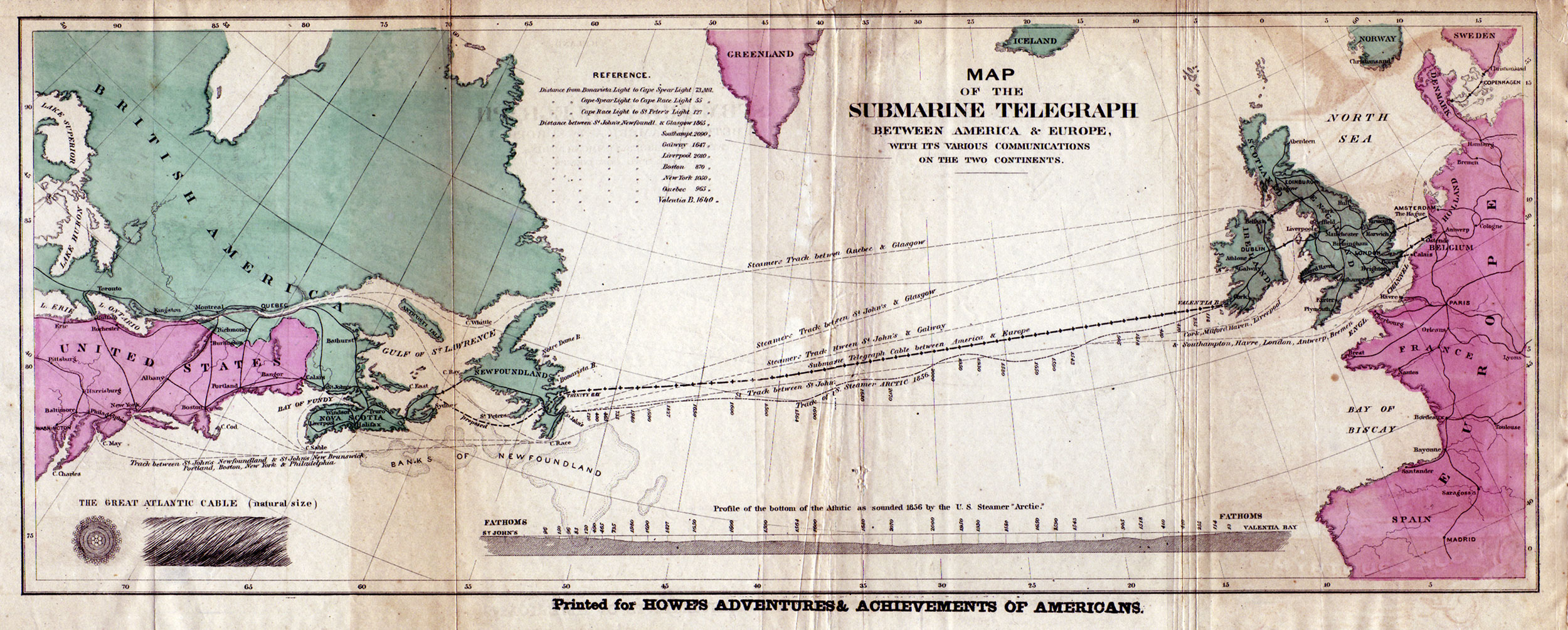

The contemporary media age can be traced back to the electrical telegraph, patented by Samuel Morse in 1837. Thanks to the telegraph, communication was no longer linked to the physical transportation of messages; it didn’t matter whether a message needed to travel five or 500 miles. Suddenly, information from distant places became nearly as accessible as local news, as telegraph lines began to stretch across the globe, making their kind of “World Wide Web.” In this way, the telegraph became a precursor to much of the technology that followed, including the telephone, radio, television, and the Internet. When the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858, which allowed nearly instantaneous communication from the United States to Europe, the London Times described it as “the greatest discovery since that of Columbus, a vast enlargement…given to the sphere of human activity.”

Not long afterward, wireless communication (which eventually led to the development of radio, television, and other broadcast media) emerged as an extension of telegraph technology. Many 19th-century inventors, including Nikola Tesla, were involved in early wireless experiments, but Italian-born Guglielmo Marconi developed the first practical wireless radio system. Early radio was used for military communication, but it soon entered the home. The burgeoning interest in radio inspired hundreds of applications for broadcasting licenses from newspapers and other news outlets, as well as from retail stores, schools, and cities. In the 1920s, large media networks, including the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), were launched, and they soon began to dominate the airwaves. In 1926, they owned 6.4 percent of U.S. broadcasting stations; by 1931, that number had risen to 30 percent.

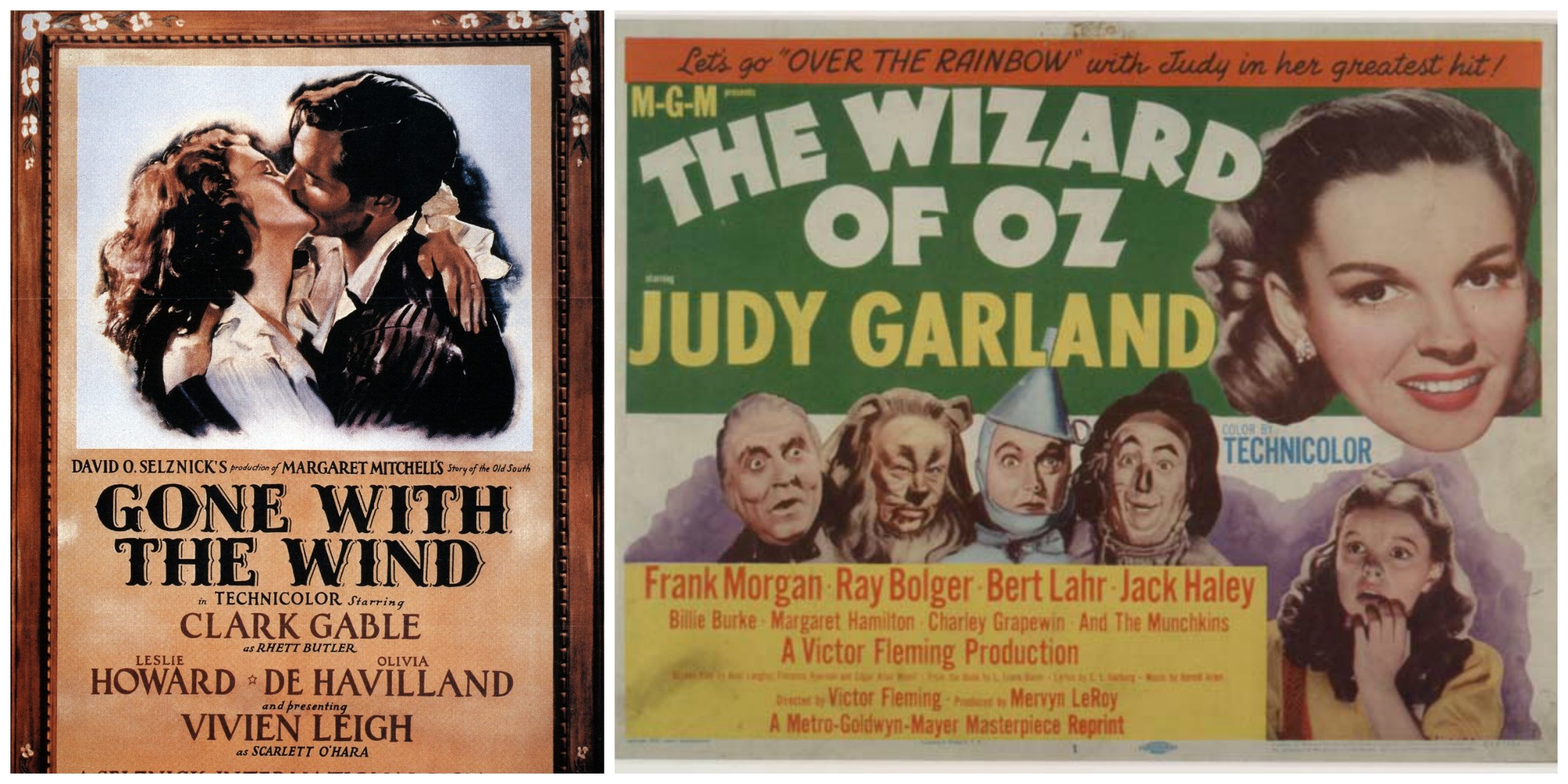

In addition to the breakthroughs in audio broadcasting, inventors in the 1800s made significant advances in visual media. The 19th-century development of photographic technologies would lead to the later innovations of cinema and television. As with wireless technology, several inventors independently created a form of photography at the same time, among them the French inventors Joseph Niépce and Louis Daguerre, and the British scientist William Henry Fox Talbot. In the United States, George Eastman developed the Kodak camera in 1888, anticipating that Americans would welcome an inexpensive, easy-to-use camera into their homes as they had with the radio and telephone. Audiences first experienced moving pictures around the turn of the century, with the first U.S. projection hall opening in Pittsburgh in 1905. By the 1920s, Hollywood had already created its first stars, most notably Charlie Chaplin. By the end of the 1930s, Americans were watching color films with full sound, including Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz.

Television existed before World War II, but gained mainstream popularity in the 1950s. In 1947, there were 178,000 television sets manufactured in the United States; five years later, that number had increased to 15 million. Radio, cinema, and live theater experienced declines in audience numbers because the new medium allowed viewers to entertain themselves with sound and moving pictures within the comforts of their homes. In the United States, the radio powerhouses of CBS and NBC applied the same principles of airing commercial-driven programming to the television networks they developed. In Great Britain, the government managed broadcasting through the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), which raised funding by charging licensing fees rather than airing advertisements. In contrast to the U.S. system, the BBC strictly regulated the length and character of commercials that stations could air. However, U.S. television (and its increasingly powerful networks) would use programming funded by advertising to dominate the television landscape. By the beginning of 1955, there were around 36 million television sets in the United States, but only 4.8 million in Europe. Critical national events, broadcast live for the first time, inspired consumers who missed them to purchase sets so they would not miss future spectacles; both England and Japan experienced a surge in sales before important royal weddings in the 1950s.

In 1969, management consultant Peter Drucker predicted that the next major technological innovation would be an electronic appliance that would revolutionize people’s lives just as thoroughly as Thomas Edison’s light bulb had. This appliance would sell for less than a television set and be “capable of being plugged in wherever there is electricity and giving immediate access to all the information needed for school work from first grade through college.” Although Drucker may have underestimated the cost of this hypothetical machine, he was prescient about the effect these machines—personal computers—and the Internet would have on education, social relationships, and the culture at large. The invention of random access memory (RAM) chips and microprocessors in the 1970s was a significant stepping stone to the Internet age. As Briggs and Burke note, these advances meant “hundreds of thousands of components could be carried on a microprocessor.” This reduction of many different kinds of content to digitally stored information signified that “print, film, recording, radio and television and all forms of telecommunications [were] now being thought of increasingly as part of one complex process.” This process, also known as convergence, is a force that’s affecting media today.