1.5 The Role of Social Values in Communication

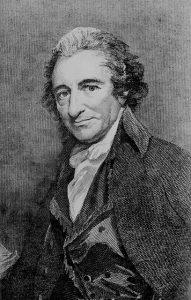

In a 1995 Wired magazine article, “The Age of Paine,” Jon Katz suggested that the Revolutionary War patriot Thomas Paine should be considered “the moral father of the Internet.” The Internet, Katz wrote, “offers what Paine and his revolutionary colleagues hoped for—a vast, diverse, passionate, global means of transmitting ideas and opening minds.” In fact, Katz said the emerging Internet era is closer in spirit to the 18th-century media world than to the 20th century’s “old media” (radio, television, print). “The ferociously spirited press of the late 1700s…was dominated by individuals expressing their opinions. The idea that ordinary citizens with no special resources, expertise, or political power—like Paine himself—could sound off, reach wide audiences, even spark revolutions, was brand-new to the world (Creel, 1920).” Katz’s defense of Paine’s plucky independence speaks to how social values and communication technologies affect the adoption of media technologies today. Keeping Katz’s words in mind, additional questions about the role of social values in communication come to mind. How do social values shape mass communication? How, in turn, does mass communication change the understanding of what society values?

Free Speech and Its Limitations

American mass communication would not have succeeded if the value of free speech had been central to the country’s existence since the nation’s revolutionary founding. The U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press. Due to the First Amendment and subsequent statutes, the United States has some of the broadest protections for speech of any industrialized nation. However, there are limits to what kinds of speech are legally protected—limits that have changed over time, reflecting shifts in U.S. social values.

Definitions of obscenity, a type of speech not protected by the First Amendment, have altered with the nation’s changing social attitudes. James Joyce’s Ulysses, ranked by the Modern Library as the best English-language novel of the 20th century, was illegal to publish in the United States between 1922 and 1934 because the U.S. Customs Court declared the book obscene due to its sexual content. The 1954 Supreme Court case Roth v. the United States defined obscenity more narrowly, allowing for differences depending on community standards. The sexual revolution and social changes of the 1960s made it even more challenging to determine what constitutes a “community standard”—a question that remains unclear to this day.

Regulations related to obscene content are not the only restrictions on First Amendment rights. Copyright law also puts limits on free speech. Intellectual property law was initially intended to protect the proprietary rights, both economic and philosophical, of the originator of a creative work. Works under copyright cannot be reproduced without the creator’s authorization, nor can anyone else use them to make a profit. Inventions, novels, musical tunes, and even phrases are all covered by copyright law. The first copyright statute in the United States established a maximum term of 14 years for copyright protection. This number has risen exponentially in the 20th century; some works are copyright-protected for up to 120 years. In recent years, an Internet culture that enables file sharing, musical mash-ups, and YouTube video parodies has raised questions about the fair use exception to copyright law. The exact line between what types of expressions are protected or prohibited by law is still being set by courts. As the changing values of the U.S. public evolve, copyright law—like obscenity law—will continue to change as well.

The Unscripted Screen: Where Reaction Meets Red Tape

Reaction videos, a ubiquitous presence on platforms like YouTube, have become a fascinating and sometimes contentious aspect of online culture. They often feature creators’ spontaneous and unscripted responses to a wide array of pop culture phenomena, from the thought-provoking imagery of Childish Gambino’s “This is America” to the classic comedic timing of Abbott and Costello’s “Who’s on First” routine, or even the jump scares and triumphs within video games like Subnautica. Their widespread popularity stems from their relatable content, which fosters diverse perspectives among viewers and builds a sense of community around shared experiences and reactions. This engagement is a powerful driver for their continued proliferation.

Despite their undeniable appeal and community-building potential, these videos frequently navigate the complex and often murky legal waters between fair use and copyright infringement. This tension was notably highlighted by Professor Devin J. Stone, known on YouTube as LegalEagle, who publicly accused streamer xQc and others of content theft. Stone’s argument hinged on the premise that these creators were broadcasting significant portions of protected material without adding sufficient value or substantive change. As Stone eloquently put it, “The transformative nature of fair use is one of the most misunderstood areas of the law on the Internet.” This statement underscores the significant challenges the legal system has grappled with since the dawn of the internet age, struggling to apply existing copyright frameworks to new forms of digital content creation (LegalEagle, 2023).

The question then arises: are all reaction videos inherently legally problematic? The answer, fortunately, is no. Many responsible reaction content creators meticulously adhere to principles that align with fair use guidelines. They often pause the media under review to interject with critical analysis, offer insightful commentary, or provide educational context. This deliberate act of transformation adds original value to the viewing experience. However, when creators simply play through large segments of copyrighted material without such meaningful additions, they risk limiting the market for the original creator’s work, as viewers might choose the free reaction video over the paid original. Simultaneously, such practices can disproportionately increase the reaction creator’s advertising revenue at the expense of the rights holder. Ultimately, when reaction video makers find themselves in court, their success in qualifying for fair use largely hinges on their ability to demonstrate the degree to which they have transformed the original content through their commentary, criticism, or new creative expression.

Propaganda and Other Ulterior Motives

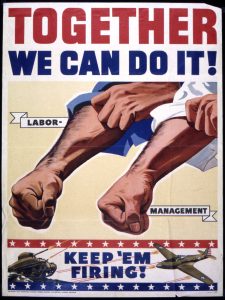

Sometimes, social values are more overtly expressed in mass media messages. Producers of media content may have vested interests in particular social goals, which, in turn, may cause them to promote or refute certain viewpoints. In its most extreme form, this type of media influence can become propaganda, a form of communication that intentionally attempts to persuade its audience for ideological, political, or commercial purposes. Propaganda often (but not always) distorts the truth, selectively presents facts, or uses emotional appeals. During wartime, propaganda can include caricatures of the enemy. Even in peacetime, however, propaganda frequently gets published and distributed through mass media platforms. Political campaign commercials, in which one candidate openly criticizes the other, remain common around election time. Some negative ads deliberately twist the truth or present outright falsehoods to attack an opposing candidate.

Other types of influence appear less blatant or sinister. Advertisers use propaganda to motivate viewers to purchase their products; some news sources, such as Fox News or The Huffington Post, demonstrate an explicit political slant. Still, people who want to exert media influence often use the tricks and techniques of propaganda. During World War I, the U.S. government created the Creel Commission as a de facto public relations firm for the United States’ entry into the war.

The Creel Commission used radio, movies, posters, and in-person speakers to present a positive slant on the U.S. war effort and to demonize the opposing Germans. Chairman George Creel acknowledged the commission’s attempt to influence the public but shied away from calling their work propaganda:

In no degree was the Committee an agency of censorship, a machinery of concealment or repression…. In all things, from first to last, without halt or change, it was a plain publicity proposition, a vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s most incredible adventures in advertising…. We did not call it propaganda, for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, as we had such confidence in our case that we felt no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of the facts (Creel, 1920).

Of course, the line between the selective (but “straightforward”) presentation of the truth and the manipulation of propaganda is not apparent or distinct. (Another of the Creel Commission’s members, Edward Bernays, was later deemed the father of public relations and authored a book titled Propaganda.) In general, public relations differs from propaganda, as PR focuses on presenting one side of the truth, while propaganda seeks to create a new “truth” altogether.

Gatekeepers

In 1960, journalist A. J. Liebling wryly observed that “freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Liebling referred to the role of gatekeepers in the media industry, another way social values influence mass communication. Gatekeepers help determine which stories reach the public, including reporters who decide which sources to use and editors who decide which stories to cover (or ignore) by the news media and which stories make it to the front page. In deciding what counts as newsworthy, entertaining, or relevant, gatekeepers pass on their values to the broader public. In contrast, stories deemed unimportant or uninteresting to consumers can linger forgotten in the back pages of the newspaper, or never get covered at all.

In one striking example of the power of gatekeeping, journalist Allan Thompson places the blame on the news media for their sluggishness in covering the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Thompson said many outside reporters failed to go to Rwanda at the height of the genocide, so the world wasn’t forced to confront the atrocities happening there. Instead, the nightly news in the United States became preoccupied with the O. J. Simpson trial, Tonya Harding’s alleged involvement in an attack on fellow figure skater Nancy Kerrigan, and the less bloody conflict in Bosnia (where more reporters were stationed). Thompson argued that the lack of international media attention provided cover for politicians, allowing them to remain complacent (Thompson, 2007). The lack of meaningful media coverage about the Rwandan atrocities meant few people expressed outrage, which contributed to a lack of political will to invest time and troops in a faraway conflict. Richard Dowden, Africa editor for the British newspaper The Independent during the Rwandan genocide, bluntly explained the news media’s larger reluctance to focus on African issues: “Africa was simply not important. It didn’t sell newspapers. Newspapers have to make a profit. So it wasn’t important (Thompson, 2007).” Bias on both the individual and institutional levels downplayed the genocide at a time of great crisis and potentially contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Gatekeepers wielded tremendous influence in the days before the Internet, as all media were subject to either space or time limitations. A news broadcast could only last for its allotted half hour, while a newspaper had a set number of pages to print. The Internet, in contrast, theoretically has the potential to host an infinite number of news reports. The interactive nature of the Internet also minimizes the gatekeeper function of legacy media outlets by allowing media consumers to have a voice as well. Sites like Reddit allow readers to upvote posts to show approval of the post’s content, or disapproval as video game producers EA Sports learned when it commented that players of Star Wars: Battlefront II didn’t mind having to unlock characters like Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker through a “loot box” experience that required hours of gameplay to achieve because “the intent is to provide players a sense of pride and accomplishment for unlocking different heroes,” an opinion so unpopular it has earned a 2020 Guinness World Record for receiving the most downvotes on the site (Leskin, 2019). Media expert Mark Glaser noted that the digital age hasn’t eliminated gatekeepers; it’s just shifted who holds these responsibilities, like those “who choose videos to spotlight on YouTube” (Glaser, 2009). Social media platforms like Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube wield immense power using algorithms that prioritize certain content, influencing what users experience on their platforms and shaping online discourse. Search engines like Google use ranking algorithms to determine what information appears at the top of search results. Social media influencers can curate and promote certain viewpoints. Unlike legacy media, these new gatekeepers rarely have public bylines, making it challenging to determine who makes such decisions and on what basis they are made.

Observing how distinct cultures and subcultures present the same story can reveal the various social values of those cultures. Another way to critically examine today’s media messages is to analyze how the media has functioned in the world and the United States during various cultural periods of the past.