10.2 The Evolution of Electronic Games

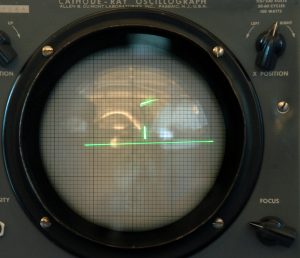

Pong, the electronic table tennis simulation game, marked the entry point into the world of video games for many people who grew up in the 1970s, and it now famously symbolizes the early days of video gaming. However, a rare few had the opportunity to experience the precursors to modern video games as early as the 1950s, if they knew where to look. In 1952, the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC), one of the first stored-information computers, developed a computer simulation of tic-tac-toe. In 1958, Brookhaven National Laboratory developed a game called Tennis for Two as a means of entertaining visitors to the laboratory on tours (Egenfeldt-Nielsen, 2008).

These games would generate little interest among the modern game-playing public. Still, at the time, they enthralled their users and introduced the basic elements of the cultural video game experience. In an era before personal computers, these games enabled the general public to interact with technology that was previously accessible only to those involved in abstract scientific fields. Tennis for Two created an interface that allowed anyone with basic motor skills to operate a complex machine. The first video games initially served as a form of media, disseminating the experience of computer technology to those who did not have access to it.

As video games evolved, their role as a form of media grew as well. Video games have evolved from simple tools that made computing technology accessible to forms of media that can convey cultural values and human relationships.

The 1970s: The Rise of the Video Game

The 1970s saw the rise of video games as a cultural phenomenon. A 1972 article in Rolling Stone describes the early days of computer gaming:

Reliably, at any nighttime moment (i.e. non-business hours) in North America hundreds of computer technicians are effectively out of their bodies, locked in life-or-death space combat computer-projected onto cathode ray tube display screens, for hours at a time, ruining their eyes, numbing their fingers in frenzied mashing of control buttons, joyously slaying their friend and wasting their employers’ valuable computer time. Something fundamental is happening (Brand, 1972).

This scene describes Spacewar!, a game developed in the 1960s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on a DEC PDP-1 minicomputer. The basic configuration of a PDP-1 cost approximately $120,000 at the time, which would be equivalent to nearly $1 million in today’s dollars. This made the computer, and thus the game, inaccessible to the general public, as it existed primarily in university and research labs. In the early ’70s, very few people owned computers. Most computer users work or study at universities, businesses, or government facilities. Those with access to computers quickly utilized them for gaming purposes.

Arcade Games

The creators of the first coin-operated arcade game, Computer Space, modeled the game on Spacewar! It performed poorly among the general public due to its complex controls and user interface. In 1972, the fledgling company Atari created Pong, the table-tennis simulator that became an immediate success. Atari initially placed Pong in bars alongside pinball machines and other games of chance, but as video games gained popularity, they were installed in any establishment that would take them. By the end of the 1970s, so many people attempted to build video arcades that some towns passed zoning laws limiting them (Kent, 1997).

The end of the 1970s ushered in a new era—what some call the golden age of video games—with the game Space Invaders, an international phenomenon that exceeded all expectations. In Japan, the game achieved such popularity that it was rumored to have caused a national coin shortage. Games like Space Invaders illustrate both the effect of arcade games and their influence on international culture. In two different countries on opposite sides of the globe, Japanese and American teenagers, although they could not speak to one another, had the same experiences thanks to a video game.

Video Game Consoles

The first home video game console began selling in 1972. The Magnavox Odyssey, based on prototypes developed by Ralph H. Baer in the late 1960s, included a Pong-type game. When the arcade version of Pong became popular, the Odyssey began to sell well. This prompted Atari to produce a home version of Pong, which was released in 1974. Although this system could only play one game, its graphics and controls surpassed the Odyssey. Due to these advantages, the Atari home version of Pong sold well, and a host of other companies began producing and selling their versions of Pong (Herman, 2008).

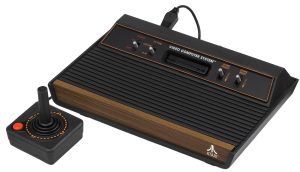

The development of game cartridges that stored the games provided a significant step forward in the evolution of video games. This allowed consoles to play multiple games. With this technology, video game console manufacturers could shift their focus to developing games. Several groups, such as Magnavox, Coleco, and Fairchild, released versions of cartridge-type consoles; however, Atari’s 2600 console had the upper hand due to the company’s expertise in arcade games. Atari capitalized on its arcade successes by releasing games that were familiar to the public and performed well in arcades. The popularity of games like Space Invaders and Pac-Man contributed to the Atari 2600’s success. The late 1970s also saw the birth of companies such as Activision, which developed third-party games like Pitfall! for the Atari 2600 (Wolf).

Home Computers

The birth of the home computer market in the 1970s paralleled the emergence of video game consoles. The Altair, the first computer designed and sold for home consumers, was first sold in 1975, primarily to a hobbyist market, several years after the introduction of the first video game consoles. During this period, people such as Steve Jobs, a co-founder of Apple, had built computers by hand and sold them to get their start-up businesses going. In 1977, three significant computers—Radio Shack’s TRS-80, the Commodore PET, and the Apple II—began production and entered the home market (Reimer, 2005).

The rise of personal computers allowed for the development of more complex games. Designers of games such as Mystery House, developed in 1979 for the Apple II, and Rogue, created in 1980 and played on IBM PCs, utilized the processing power of early home computers to build video games with extended plots and storylines. In these games, players navigate landscapes composed of basic graphics, solving puzzles and progressing through an engaging narrative. These games eclipsed the capabilities of text-based games like Zork. The development of video games for the personal computer platform expanded the capabilities of video games as a medium by hosting complex stories and introducing new forms of interaction between players.

The 1980s: The Crash and Rebound

Atari owed its success in the home console market in large part to its ownership of already-popular arcade games and the large number of game cartridges available for the system. These strengths, however, eventually proved detrimental to the company and led to the video game crash of 1983. Atari bet heavily on its past successes with popular arcade games by releasing Pac-Man for the Atari 2600. The successful arcade game did not translate well to the home console after rushing its production, leading to disappointed consumers and lower-than-expected sales. Additionally, Atari produced 12 million of the lackluster Pac-Man games on its first run, even though it meant they had made more than one copy for every console they had sold up to that point. A game based on the movie E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial gained notoriety as one of the worst games in Atari’s history. Consumers disliked the confusing game, despite the movie’s success, and Atari had again bet heavily on its success. Atari buried piles of unsold E.T. game cartridges in the New Mexico desert under a veil of secrecy, which were eventually found (Monfort & Bogost, 2009).

As retail outlets became increasingly wary of home console failures, they began stocking fewer games on shelves. This action, combined with an increasing number of companies producing games, led to overproduction and a resulting fallout in the video game market in 1983. Many smaller game developers were unable to withstand this downturn and went out of business. Although Coleco and Atari survived the crash, neither company regained its former share of the video game market. Some speculated the home video game market would never recover.

The Rise of Nintendo

Nintendo, a Japanese card and novelty producer that began producing electronic games in the 1970s, enjoyed success with arcade games such as Donkey Kong in the early 1980s. Its first home console, the Famicom, developed in 1984 for sale in Japan, tried to succeed where Atari had failed. The Nintendo system utilized newer, higher-quality microchips, purchased in large quantities, to ensure high-quality graphics at a price consumers could afford. Keeping console prices low meant Nintendo had to rely on games for most of its profits and maintain control of game production. Atari had failed to do this, and it led to a glut of low-priced games that contributed to the 1983 crash. Nintendo addressed this problem by incorporating proprietary circuits that prevented the console from playing unlicensed games. This allowed Nintendo to dominate the home video game market through the end of the decade, when one-third of homes in the United States had a Nintendo system (Cross & Smits, 2005).

Nintendo introduced its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in the United States in 1985. This 8-bit system ushered in the third generation of consoles, dramatically advancing home gaming with superior graphics and processing power compared to its predecessors. The game Super Mario Bros., released with the system, signified a landmark in video game development. The game employed a narrative similar to that of more complex computer games, but it featured accessible controls and straightforward objectives. The game appealed to a younger demographic, generally boys in the 8–14 age range, than the one targeted by Atari (Kline et al., 2003). Its designer, Shigeru Miyamoto, attempted to recreate the experiences of childhood adventures, creating a fantasy world that was not based on previous models of science fiction or other literary genres (McLaughlin, 2007). Super Mario Bros. also gave Nintendo an iconic character whom they have since used in numerous other games, television shows, and even two movies. The development of this type of character and fantasy world became the norm for video game makers. Games such as The Legend of Zelda have become franchises with film and television possibilities, rather than simply one-off games.

As video games developed into a form of media, the public struggled to come to terms with the kind of messages this medium conveyed to children. These games did not resemble the simple reflex games comparable to similar non-video games or sports; instead, these forms of media included stories and messages that concerned parents and children’s advocates. Arguments about the broader meaning of the games became common, with some viewing the games as driven by ideas of conquest and gender stereotypes. In contrast, others saw them as basic stories about travel and exploration (Fuller & Jenkins, 1995).

Other Home Console Systems

Other software companies attempted to establish themselves in the home console market in the mid-1980s. Atari released the 2600 Jr. and the 7800 in 1986, following Nintendo’s success, but the consoles were unable to compete with Nintendo. The Sega Corporation, which had produced arcade video games, released its Sega Master System in 1986. Although the system had more graphics possibilities than the NES, Sega failed to make a dent in Nintendo’s market share until the early 1990s, with the release of the Sega Genesis (Kerr, 2005).

Computer Games Flourish and Innovate

The enormous number of games available for Atari consoles in the early 1980s took its toll on the video arcade industry. In 1983, arcade revenues had fallen to a three-year low, leading game makers to turn to newer technologies that home consoles could not replicate. This included stunningly animated arcade games powered by laser discs, such as Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace. Still, their novelty soon wore off due to the simplistic nature of the gaming interface, and laser-disc games became museum pieces (Harmetz, 1984). In 1989, museums already curated exhibitions of early arcade games that included ones from the early 1980s. Although newer games continued to be released on arcade platforms, they could not compete with the home console market and never achieved the same level of success as they had in the early 1980s. Increasingly, arcade gamers chose to stay at home to play games on computers and consoles. Today, dedicated arcades represent a dying breed. Most that remain, such as Dave & Buster’s and Chuck E. Cheese’s chains, offer full-service restaurants and other entertainment attractions (e.g., redemption games, virtual reality experiences, sports viewing, party rooms) to draw in business.

The Unlikely Ace: Golden Tee’s Enduring Swing in a Fading Arcade World

Although arcade games have mostly fallen out of favor, Golden Tee, the iconic arcade golf game developed by Incredible Technologies, has maintained an extraordinary level of popularity and impact since its inception in 1989. Its signature trackball control, allowing players to meticulously shape their golf shots with power, direction, and curve, quickly sets it apart. While the initial releases garnered a following, the series truly exploded in popularity with the release of Peter Jacobson’s Golden Tee 3D Golf in 1995. This version introduced online networked play, a groundbreaking feature for its time, enabling competitive tournaments across different cabinets and fostering a vibrant community of players.

The game’s genius lies in its accessibility—easy to pick up for casual players, yet incredibly challenging to master, attracting a dedicated competitive scene. Golden Tee became a ubiquitous fixture in bars, pubs, and restaurants across North America, often referred to as the “pool table of the next generation” due to its social appeal and ability to generate consistent revenue for establishments. Its enduring legacy is marked by yearly updates with new courses and features, a testament to its sustained appeal. It even pioneered early forms of esports, with real-money tournaments dating back to the mid-90s, well before the term “esports” became mainstream, demonstrating its significant and long-lasting influence on both casual gaming culture and competitive play.

Home games fared better than arcades because they could capitalize on the surge in personal computer purchases that occurred in the 1980s. Some significant developments in video games happened in the mid-1980s with the development of online games. Multiple players could role-play simultaneously in multiuser dungeons, also known as MUDs. The generally text-based games described the world of the MUD through text rather than illustrating it through graphics. The games allowed users to create a character and move through different worlds, accomplishing goals that awarded them with new skills. If characters attained a certain level of proficiency, they could then design their area of the world. Habitat, a game developed in 1986 for the Commodore 64, added graphics to the storyline. Users dialed up on modems to a central host server and then controlled characters on screen, interacting with other users (Reimer, 2005).

During the mid-1980s, a demographic shift occurred. Between 1985 and 1987, the percentage of games designed to run on business computers rose from 15 percent to 40 percent of the total games sold (Elmer-Dewitt et al., 1987). This trend allowed game makers to utilize the increased processing power of business computers to create more complex games. It also demonstrated that adults had an interest in computer games and could become a profitable market.

The 1990s: The Rapid Evolution of Video Games

Video games evolved rapidly throughout the 1990s, progressing from the first 16-bit systems (named for the amount of data they could process and store) in the early 1990s to the first Internet-enabled home console in 1999. As companies focused on new marketing strategies, they targeted broader audiences, and the influence of video games on culture began to expand.

Console Wars

Nintendo’s dominance of the home console market throughout the late 1980s allowed it to build an extensive library of games for use on the NES. This also proved problematic, however, because Nintendo showed reluctance to improve or change its system, fearing it would make its game library obsolete. Technology had changed in the years since the introduction of the NES, and companies such as NEC and Sega prepared to challenge Nintendo with 16-bit systems (Slaven).

NEC’s TurboGrafx-16 struggled to become a major competitor against Nintendo (and later Sega) due to a combination of factors, including a confusing marketing strategy, a higher price point for the console and its essential accessories (like the multi-player adapter), and a limited software library in North America compared to the well-established NES and the rapidly rising Genesis. Despite its innovative hardware and early adoption of CD-ROM technology, these challenges prevented it from gaining significant market share. The Sega Master System had failed to challenge the NES, but with the release of its 16-bit system, Sega Genesis, the company pursued a new marketing strategy. Whereas Nintendo targeted 8- to 14-year-olds, Sega’s marketing plan targeted 15- to 17-year-olds, making more mature games and advertising them during programs such as the MTV Video Music Awards. The campaign successfully branded Sega as a more appealing alternative to Nintendo, shifting mainstream video games into a more mature arena. Nintendo responded to the Sega Genesis with its 16-bit system, the Super NES, and began creating more mature games as well. Games such as Sega’s Mortal Kombat and Nintendo’s Street Fighter II competed to raise the level of violence that could be depicted in a video game. Sega’s advertisements even suggested that it made a better game because of its more violent possibilities (Gamespot).

By 1994, companies such as 3DO, with its 32-bit system, and Atari, with its allegedly 64-bit Jaguar, attempted to enter the home console market but failed to utilize effective marketing strategies to support their products. Both systems were discontinued before the end of the decade. Sega, fearing that its system would become obsolete, released the 32-bit Saturn system in 1995. They rushed the system into production and did not have enough games available to ensure its success (Cyberia PC). Sony stepped in with its PlayStation console at a time when Sega’s Saturn floundered and before Nintendo could release its 64-bit system. This system targeted an even older demographic of 14- to 24-year-olds and had a significant impact on the market; by March 2007, Sony had sold 102 million PlayStations (Edge Staff, 2009). The PlayStation console revolutionized the industry by embracing CDs for game distribution, which significantly reduced manufacturing costs and allowed for larger, more intricate games. The PlayStation also brought true 3D graphics to the forefront of console gaming, captivating audiences with immersive new worlds, with popular games including Final Fantasy VII, Gran Turismo, and Tekken 3.

Computer Games Gain Mainstream Acceptance

Computer games had avid players, but they still represented a niche market in the early 1990s. The development of the first-person shooter genre marked a significant step in the mainstream acceptance of personal computer games. First popularized by the 1992 game Wolfenstein 3D, these games put the player in the character’s perspective, allowing them to experience the sensation of firing weapons and attacking enemies. Doom, released in 1993, and Quake, released in 1996, used the increased processing power of personal computers to create vivid three-dimensional worlds that video game consoles of the era could not replicate. These games pushed realism to new heights and began attracting public attention for their graphic violence.

The game Myst, an adventure game where the player walked around an island solving a mystery, drove sales of CD-ROM drives for computers and motivated audiences outside of the video-game-playing community to explore the medium. In the 1990s, Myst, its sequel Riven, and other non-violent games, such as SimCity and Sid Meier’s Civilization, demonstrated the growing popularity of alternative game genres alongside the dominance of action titles like Doom and Quake (Miller, 1999). These nonviolent games appealed to people who did not generally play video games, thereby increasing the form’s audience and expanding the types of information that video games conveyed.

Online Gaming Gains Popularity

A significant advance in game technology occurred with the widespread adoption of the Internet by the general public in the 1990s. Doom enabled multiplayer gaming over the Internet, a significant factor in its appeal. Strategy games such as Command & Conquer and Total Annihilation also included options that allowed players to play each other over the Internet. Other fantasy-inspired role-playing games, such as Ultima Online, helped establish the massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) genre by utilizing the Internet (Reimer). These games used the Internet as their platform, much like the text-based MUDs, creating a space where individuals could play the game while engaging in social interaction with one another.

Portable Game Systems

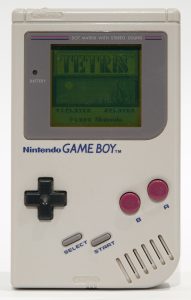

The development of portable game systems boosted another vital aspect of video game evolution during the 1990s. People could purchase handheld electronic games as early as the 1970s, and the early 1980s saw the introduction of a handheld system with interchangeable cartridges. Nintendo released the Game Boy in 1989, using the same principles that made the NES dominate the handheld market throughout the 1990s. Nintendo bundled the Game Boy with Tetris, using the game’s popularity to drive purchases of the unit. The unit’s simple design meant users could get 20 hours of playing time on a set of batteries, and Nintendo left this basic design essentially unaltered for most of the decade. More advanced handheld systems, such as the Atari Lynx and Sega Game Gear, could not compete with the Game Boy despite their superior graphics and color displays (Hutsko, 2000).

The decade-long success of the Game Boy belies the conventional wisdom of the console wars, which holds that more advanced technology makes for a more popular system. Audiences found the Game Boy’s static, simple design easy to use, and its stability allowed for the development of an extensive library of games. Despite using nearly a decade-old technology, the Game Boy accounted for 30 percent of Nintendo of America’s overall revenues at the end of the 1990s (Hutsko, 2000).

Level Up or Lose Out: The Titans Reshaping the Video Game Industry

The video game manufacturing landscape experienced rapid consolidation during the 1990s. This trend continues to shape the industry today as major publishers absorb smaller studios and expand their market reach. Among the most prominent players are Nintendo, represented by its highly successful console and iconic franchises. but many companies vie to be the world’s most successful publisher of video game entertainment.

Activision Blizzard, once recognized as one of the world’s largest interactive entertainment companies, is now part of Microsoft, following a substantial acquisition completed in October 2023 for approximately $68.7 billion. Before this landmark deal, Activision Blizzard was celebrated for its highly popular franchises, including Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, Overwatch, and Candy Crush. The company’s growth was significantly fueled by strategic acquisitions, including Blizzard Entertainment in 2007 and King Digital Entertainment in 2016. However, Activision Blizzard also faced considerable controversies in recent years, notably stemming from widespread allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination within its workplace.

Electronic Arts (EA) is one of the oldest and largest American gaming companies, distinguished by its extensive portfolio and a strong focus on digital distribution, including its platforms and subscription services such as EA Play. EA’s popular franchises span various genres, most notably in sports with titles like FIFA (now EA Sports FC) and Madden NFL, alongside iconic series such as The Sims, Battlefield, and Apex Legends. The company’s expansion has been bolstered by numerous acquisitions over the years, including key developers such as BioWare and Maxis. Despite its commercial success, EA has frequently faced public criticism regarding its business practices and monetization strategies within its games.

Ubisoft, a major French video game company, holds a prominent position as one of Europe’s largest gaming entities, known for its extensive global presence with studios worldwide. The company is responsible for a strong lineup of popular open-world action-adventure and shooter franchises, including Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry, Watch Dogs, and Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six. While often lauded for its innovative approach to game design and technology, Ubisoft, like other industry leaders, has not been immune to controversies, including significant allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination, as well as recent criticisms over confident game design choices and digital rights policies.

The 2000s: The Console Wars Continue and Gaming Expands

This century, three major companies dominate the home console market: Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft. Sega gave its final effort in the console wars with the Sega Dreamcast in 1999. This console could connect to the Internet, emulating the sophisticated computer games of the 1990s. The new features of the Sega Dreamcast could not save the brand, however, and Sega discontinued production in 2001, leaving the console market entirely (Business Week).

Sony’s release of the PlayStation 2 (PS2) in 2000 likely caused the Dreamcast’s downfall on its way to becoming the best-selling console of all time. The PS2 could function as a DVD player, expanding the console’s role into an entertainment device that did more than play video games. Nikkei Online conducted a survey in Japan and found more than 60% of the participants said they used the PS2 primarily as a DVD player. This console enjoyed an incredible production run, with more than 106 million units sold worldwide by the end of the decade and supported by a vast array of titles from popular franchises like Gran Turismo, Final Fantasy, and Metal Gear Solid (A Brief History of Game Console Warfare).

In 2001, two major consoles attempted to compete with the PS2: the Xbox and the Nintendo GameCube. The Xbox represented Microsoft’s attempt to enter the market with a console that expanded on the functions of other game consoles. The unit had features similar to a PC, including a hard drive and an Ethernet port for online play through its service, Xbox Live. The popularity of the first-person shooter game Halo, an Xbox exclusive, also boosted sales. Nintendo’s GameCube did not offer DVD playback capabilities; instead, it focused on gaming functions. Both of these consoles sold millions of units but did not come close to the sales of the PS2.

Microsoft’s Xbox 360 expanded media capabilities and integrated access to Xbox Live, an online gaming service. Sony’s PlayStation 3 (PS3) followed in 2006. It also featured enhanced online access as well as expanded multimedia functions, with the additional capacity to play Blu-ray discs. Popular games included the Uncharted series and The Last of Us. Nintendo released the Wii at the same time. This console featured a motion-sensitive controller that departed from previous controllers, focusing on accessible, often family-oriented games. This combination successfully brought in large numbers of new game players, including many older adults. The console’s appeal was broadened by bundled titles like Wii Sports, which expertly showcased the motion controls, and a vast library of family-friendly games like Mario Kart Wii and Super Mario Galaxy. By June 2010, in the United States, the Wii had sold 71.9 million units, the Xbox 360 had sold 40.3 million, and the PS3 trailed at 35.4 million (VGChartz, 2010). In the wake of the Wii’s success, Microsoft released Kinect and Sony released the PlayStation Move to incorporate motion-sensitive systems, but neither sold as many units. However, Kinect arguably laid the groundwork for Microsoft’s future ventures into virtual reality (Mangalindan, 2010).

Nintendo released the Wii U in 2012, an attempt to bridge the gap between traditional console gaming and tablet-style interaction. Its defining feature was the GamePad, a large controller with an integrated touchscreen that allowed for “asymmetric gameplay,” where one player could have a unique view or control scheme. The Wii U also introduced Miiverse, an early social network for gamers discontinued in 2017, and continued Nintendo’s tradition of offering engaging local multiplayer experiences. While it struggled commercially compared to its predecessor, it nonetheless gave birth to critically acclaimed titles that would later find massive success in its successor, such as Mario Kart 8, Super Mario 3D World, and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, which IGN has ranked as the best video game ever made.

Following closely, Sony launched the PlayStation 4 (PS4) in 2013, quickly establishing itself as a dominant force in the market. The PS4 emphasized powerful hardware and a developer-friendly architecture, leading to stunning graphical fidelity and seamless gameplay experiences. Innovative features included the DualShock 4 controller, which featured an integrated touchpad and Share button, facilitating easy content sharing on social media and for live streaming. Remote Play enabled users to stream games to other devices, such as the PlayStation Vita, expanding gameplay beyond the main TV. The console’s success was driven by a robust library of exclusive titles, including God of War, Marvel’s Spider-Man, Horizon Zero Dawn, and The Last of Us Part II, alongside major third-party releases such as Grand Theft Auto V and Red Dead Redemption 2.

Microsoft’s entry in 2013 was the Xbox One, initially positioned as an all-in-one entertainment system with a strong focus on media integration through HDMI pass-through and a refined Kinect sensor for voice and gesture control. While its initial emphasis on multimedia and always-online features faced some resistance, Microsoft quickly pivoted to focus on gaming. Key innovations included the improved Xbox Wireless Controller with impulse triggers, cloud-powered processing, and the groundbreaking Xbox Game Pass subscription service, which offered a vast library of games for a monthly fee. Popular titles that defined the Xbox One era included Halo 5: Guardians, Forza Horizon 3 and 4, Gears 5, and a wide array of third-party hits, such as Fortnite and Minecraft.

The Nintendo Switch, released in 2017, revolutionized console design with its hybrid nature, allowing players to seamlessly switch between TV mode, tabletop mode with its kickstand, and handheld portable mode. This versatility, combined with its detachable Joy-Con controllers offering HD Rumble and motion controls, made it a unique and immensely popular system. The Switch also fostered innovative local multiplayer, allowing players to share a single Joy-Con. Its success was monumental, propelled by beloved first-party titles like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Super Mario Odyssey, Animal Crossing: New Horizons, and Mario Kart 8 Deluxe, which showcased the console’s unique playstyles and broad appeal across all demographics.

Most recently, both Sony and Microsoft launched their next-generation consoles in late 2020: the PlayStation 5 (PS5) and the Xbox Series X|S. Both systems push the boundaries of performance with ultra-fast custom SSDs for near-instant load times, significantly more powerful GPUs enabling 4K resolution at high frame rates, and hardware-accelerated ray tracing for incredibly realistic lighting. The PS5 features the innovative DualSense controller, offering highly immersive haptic feedback and adaptive triggers that provide varying levels of force and tension for unparalleled tactile sensations. The Xbox Series X|S introduced Quick Resume, allowing players to instantly switch between multiple games, and Smart Delivery, ensuring players always have the optimal version of a game for their console. Both consoles boast impressive backward compatibility, allowing players to enjoy thousands of games from previous generations with improved performance. Blockbuster titles for this generation include God of War Ragnarök, Marvel’s Spider-Man 2, and Horizon Forbidden West for PS5, and Halo Infinite, Forza Motorsport, and Starfield (after its acquisition by Microsoft) for Xbox, in addition to major multi-platform hits like Elden Ring and Baldur’s Gate 3.

Building on Nintendo’s legacy, the highly anticipated Nintendo Switch 2 launched in 2025, further solidifying the company’s innovative approach to gaming hardware. The Switch 2 retains the successful hybrid console design, seamlessly transitioning between handheld, tabletop, and docked TV modes, much like its predecessor. However, it introduces significant upgrades, and its increased horsepower has allowed for enhanced versions of beloved existing games, such as The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild – Nintendo Switch 2 Edition and Tears of the Kingdom – Nintendo Switch 2 Edition, which now benefit from visual upgrades and smoother performance. New launch titles, such as Mario Kart World and Donkey Kong Bananza have been lauded as masterpieces, showcasing the console’s capabilities with intricate level design and dynamic gameplay.

The Enduring Evolution and Expansion of Computer Gaming

Since the turn of the millennium, computer gaming has not merely persisted but has undergone a profound evolution, cementing its status as a dynamic and ever-expanding segment of the entertainment industry. The period from 2000 to the present has been marked by continuous innovation and a burgeoning player base. The early 2000s witnessed the rise of groundbreaking online experiences, notably the explosion of massively multiplayer online (MMO) games like World of Warcraft, which cultivated vast, persistent virtual worlds and fostered unprecedented levels of player community and long-term engagement.

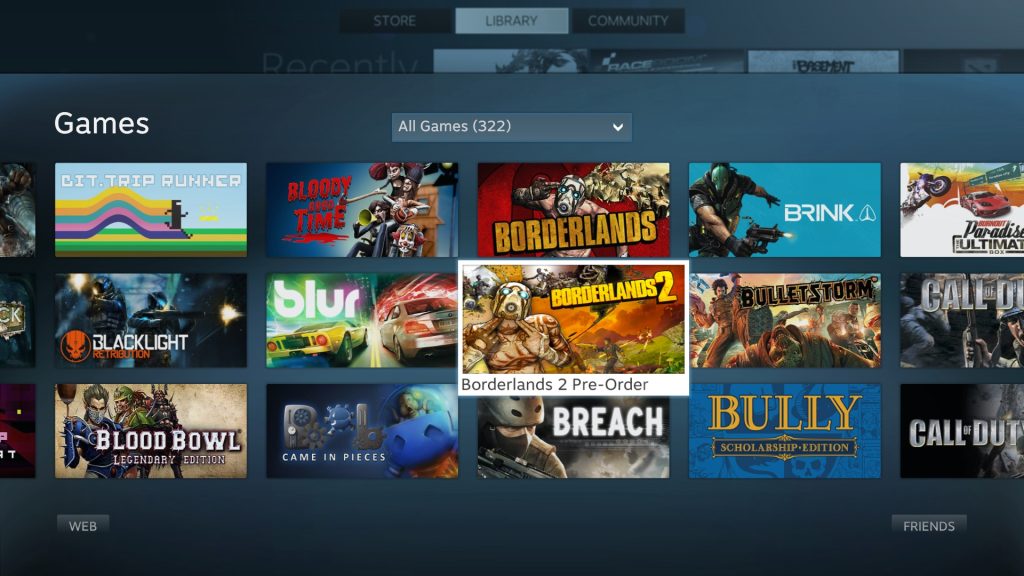

A pivotal development was the widespread adoption of digital distribution platforms. Steam, launched in 2003, revolutionized how computer games were purchased, managed, and updated, making a colossal library of titles instantly accessible and often more affordable. This digital shift empowered independent developers, leading to a vibrant indie game scene that brought immense creative diversity and experimental gameplay to the forefront. Concurrently, computer gaming became the undisputed foundation for the global phenomenon of esports, with competitive titles like League of Legends, Dota 2, and Counter-Strike driving professional leagues, massive tournaments, and attracting millions of spectators on streaming platforms such as Twitch.

The computer gaming community, while always valuing high performance, has diversified beyond just the most dedicated enthusiasts. While a segment of players continues to invest in powerful, custom-built gaming PCs with advanced hardware and multi-monitor setups for cutting-edge experiences, the ecosystem has also become more accessible. Innovations in hardware, coupled with the flexibility for user-generated content (mods) that vastly extend game longevity and replayability, have ensured that computer gaming remains at the forefront of technological advancement in the industry. This blend of evolving distribution models, diverse game offerings across all genres, and a robust, engaged community underscores computer gaming’s enduring appeal and its significant, continuous growth throughout the 21st century.

The Evolution of Portable Gaming

Nintendo continued to dominate the handheld game market into the 2000s with the 2001 release of the Game Boy Advance, a redesigned Game Boy that offered 32-bit processing and compatibility with older Game Boy games. In 2004, anticipating Sony’s upcoming handheld console, Nintendo released the Nintendo DS, a handheld console that featured two screens and Wi-Fi capabilities for online gaming. Sony released the PlayStation Portable (PSP) the following year. The device featured Wi-Fi capabilities as well as a flexible platform that could play other media such as MP3s (Patsuris, 2004). Although the Nintendo DS (and later the 3DS) and PSP enjoyed great popularity (the DS is Nintendo’s best-selling console of all time), handheld game consoles would eventually lose most of their market share to a different mobile device: the smartphone.

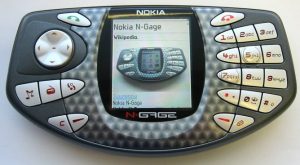

One interesting innovation in mobile gaming occurred in 2003 with the release of the Nokia N-Gage. The N-Gage combined a game console and mobile phone, which, according to consumers, did not excel in either role. Nokia discontinued the product line in 2005, but the idea of playing games on phones persisted (Stone, 2007). The mobile phone gaming industry has since burgeoned into a colossal market, far surpassing its nascent beginnings to become a dominant force in global entertainment. While Apple’s App Store historically led in terms of revenue generation, the landscape has evolved into a duopoly, with Android now boasting a larger global user base. This immense growth is reflected in recent figures: in 2023, global mobile game revenue soared to an impressive $76.7 billion, and forecasts suggest this figure could exceed $100 billion by 2028, with the United States consistently remaining the largest market for this burgeoning sector.

Modern innovations in portable gaming on smartphones extend well beyond the simple act of downloading an app, transforming these devices into sophisticated gaming platforms. Cloud gaming services, such as Xbox Cloud Gaming, NVIDIA GeForce NOW, and Amazon Luna, enable users to stream high-fidelity, console-quality games directly to their smartphones. This eliminates the need for powerful local hardware and extensive downloads, a capability significantly enhanced by the advent of 5G connectivity, which provides the crucial high speeds and low latency necessary for a seamless streaming experience.

Simultaneously, the hardware within flagship smartphones has advanced dramatically. These devices now feature stunning OLED displays with high refresh rates, reaching up to 185Hz, coupled with powerful processors like the Snapdragon 8 Elite. To manage the demands of intensive gaming, they incorporate internal cooling chambers and offer expansive storage capacities up to 1TB. Furthermore, specialized “gaming phones” from brands like Asus (ROG Ally X Phone) and Nubia (RedMagic) push these boundaries even further, integrating dedicated features such as ultrasonic shoulder buttons and advanced cooling systems for optimal performance.

Immersive technologies are also redefining the mobile gaming experience. Haptic feedback has become remarkably sophisticated, delivering nuanced vibrations that realistically simulate in-game actions, from subtle movements to powerful explosions, thereby greatly enhancing player immersion. Augmented Reality (AR) games, famously popularized by titles like Pokémon Go, continue to evolve, seamlessly overlaying digital elements onto the real world to create dynamic, interactive, and location-based experiences that blend the virtual with the physical.

The business models supporting mobile gaming have diversified as well. Subscription services, including Apple Arcade and Google Play Pass, offer curated libraries of games for a monthly fee, often distinguished by being ad-free and devoid of in-app purchases, providing a “Netflix-like” approach to mobile gaming consumption. Even traditional streaming giants like Netflix have entered this space, integrating mobile games directly into their existing subscription offerings. This era also champions connectivity, with many popular titles such as Fortnite and Call of Duty: Mobile supporting cross-platform play, allowing mobile gamers to compete directly with players on consoles and PCs. Alongside this, cross-progression features ensure that players can seamlessly continue their game progress across various devices, offering unparalleled flexibility. Looking ahead, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly being integrated into mobile games, promising more personalized experiences, dynamically adaptive non-playable characters (NPCs), and even adaptive storytelling, further enriching the mobile gaming landscape

Current Trends

The contemporary video game industry is characterized by several dynamic trends that are fundamentally reshaping how games are developed, distributed, and played. A significant shift is the increasing move towards digital-only platforms, with many gaming systems now offering or prioritizing digital downloads and online access over physical discs. Services like Steam, primarily a PC gaming platform, along with Xbox’s extensive ecosystem (including Xbox Cloud Gaming) and Ubisoft Connect, are at the forefront of this shift, enabling gamers to access and play their titles across an expanding array of devices, from traditional PCs and consoles to mobile phones and smart TVs. This push towards digital convenience is further enhanced by popular streaming platforms like Twitch, which has become a central hub for live gameplay, esports, and community interaction, influencing how games are consumed and shared.

Beyond distribution, cloud gaming has emerged as a transformative force. Services such as Amazon Luna and Microsoft’s Xbox Cloud Gaming allow players to stream demanding titles directly to their devices, effectively eliminating the need for expensive, powerful local hardware. This technology significantly broadens accessibility, making a vast library of games available on everything from smartphones and tablets to web browsers and smart televisions, democratizing access to high-fidelity gaming experiences. Complementing this, mobile gaming continues its reign as the largest segment of the global gaming industry, driven by its unparalleled accessibility on smartphones and tablets, primarily through the prevalent free-to-play model that leverages in-app purchases for revenue.

The indie game scene also continues to thrive, offering immense creative diversity and pushing the boundaries of traditional genres and gameplay mechanics. Critically acclaimed titles such as the Metroidvania-style Hollow Knight and Ori and the Blind Forest, narrative-driven experiences like Night in the Woods and Outer Wilds, and visually distinct pixel art games like Celeste and Undertale showcase the independent sector’s ability to achieve both commercial success and widespread critical acclaim. Furthermore, unique gameplay experiences such as the innovative puzzle design of Baba Is You and The Witness and the whimsical mischief of Untitled Goose Game highlight the indie community’s relentless pursuit of novel interactive forms.

Further shaping the industry are “live service games” and the broader “Game-as-a-Service” (GaaS) model. Live service games receive continuous updates, new content, events, and features, fostering long-term player engagement and loyalty, essentially treating games as evolving platforms rather than one-off products. Concurrently, GaaS platforms like Xbox Game Pass and PlayStation Plus offer subscribers extensive libraries of games for a recurring monthly fee, providing immense convenience and value for gamers. These trends—from the shift to digital and cloud-based gaming to the flourishing indie scene and the pervasive live service and GaaS models—are fundamentally altering the landscape of the video game industry, creating exciting new opportunities for both players and developers. Virtual and augmented reality are also gaining significant traction, with VR offering deeply immersive experiences and AR blending digital elements with the real world, further expanding the horizons of interactive