10.4 The Impact of Video Games on Culture

In the United States, video games remain a pervasive form of entertainment. Recent data from the Entertainment Software Association (ESA) in their 2024 “Essential Facts About the U.S. Video Game Industry” report indicates that 61% of Americans aged 5-90 play video games, translating to approximately 190.6 million people engaging with games for at least one hour each week. This figure underscores the widespread adoption of gaming across diverse demographics. Another report from Activision Blizzard Media in April 2025 suggests even higher engagement, stating that 86% of the U.S. population plays video games, with most active across multiple platforms, including mobile, console, and PC. In 2010, more people spent time playing video games than checking or writing email. This effect becomes visible in the growing mainstream acceptance of aspects of gaming culture. Video games have also altered the production and consumption of various other forms of media, including music and film. However, their most profound impact may be in the field of education through the integration of innovative technologies that foster new avenues for communication and learning. Modern educational games and gamified learning platforms now offer immersive and interactive experiences that blend entertainment with core curriculum, leveraging elements like virtual reality, augmented reality, and collaborative gameplay to enhance student engagement, critical thinking, and communication skills.

Game Culture

Video games, like books or movies, have avid users who have made this form of media a central part of their lives. In the early 1970s, programmers gathered in groups to play Spacewar!, spending a considerable amount of time competing in a rudimentary game compared to modern titles (Brand). As video arcades and home video game consoles gained popularity, youth culture quickly adapted to this type of media, engaging in competitions to achieve high scores and spending hours at the arcade or with their home consoles.

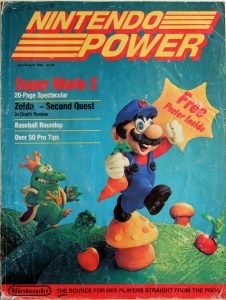

In the 1980s, an increasing number of children spent time playing games on consoles and, more importantly, increasingly identified with the characters and products associated with these games. Networks developed Saturday morning cartoons based on the Pac-Man and Super Mario Bros. games, and game companies sold a wide array of non-game merchandise featuring video game logos and characters. The public recognition of some of these characters has made them into cultural icons. A 2007 poll found that more Canadians surveyed could identify a photo of Mario from Super Mario Bros. than a photo of the current Canadian prime minister (Cohn & Toronto, 2007). Nintendo Power, published from 1988 to 2012, was Nintendo’s official magazine in North America, serving as a vital source of news, strategies, and previews for a generation of gamers in the pre-Internet era. Its unique blend of insider information, vibrant artwork, and engaging content, including the iconic “Howard & Nester” comic, fostered a strong sense of community and significantly shaped Nintendo’s cultural presence during its golden age.

As the generations who first played iconic titles like Super Mario Bros. matured, the video game industry, including companies like Sega, Sony, and Microsoft, strategically broadened its appeal to older demographics. This shift has significantly increased the average age of video game players, which, according to the Entertainment Software Association’s 2024 “Essential Facts” report, now stands at 36 years old in the U.S. Modern gaming has found a strong foothold among older adults through diverse platforms, including smartphones, tablets, and even current-generation consoles like the Nintendo Switch, Xbox, and PlayStation. The AARP reports that 44% of adults over 50 play games monthly, engaging with titles ranging from casual puzzle games, such as Candy Crush Saga, and word games like Words With Friends, to more complex strategy games, often citing benefits for mental sharpness, stress relief, and social connection. This widespread adoption across age groups has firmly cemented video games as an accepted and integral form of mainstream entertainment.

The Revenge of the Nerds: How Gaming Changed the Definition of “Geek”

The acceptance of video games in mainstream culture has consequently changed the way that the culture views certain people. People applied the term “Geek” to those adept at technology but lacking in the skills that tended to make one popular, like fashion sense or athletic ability. Many of these individuals, who often did not fare well in society, favored imaginary worlds, such as those found in the fantasy and science fiction genres. Video games appealed to them because they both took place in a fantasy world and offered a means to excel at something. Jim Rossignol, in his 2008 book This Gaming Life: Travels in Three Cities, explained part of the lure of playing Quake III online:

Cold mornings, adolescent disinterest, and a nagging hip injury had meant that I was banished from the sports field for many years. I wasn’t going to be able to indulge in the camaraderie that sports teams felt or in the extended buzz of victory through dedication and cooperation. That entire swathe of experience had been cut off from me by cruel circumstance and a good dose of self-defeating apathy. Now, however, there was a possibility for some redemption: a sport for the quick-fingered and the computer-bound; a space of possibility in which I could mold friends and strangers into a proficient gaming team (Rossignol, 2008).

Video games provided a means for a group of previously excluded individuals to develop social proficiency. As video games became a more mainstream phenomenon and a large number of people began to desire improvement in their video game skills, the popular idea of geeks evolved. The term “geek” no longer carries the negative connotations it once did. It now refers to a person who has a deep understanding of computers and technology. This former slur appears often in the media, with headlines such as “Turning Geek Into Chic” and “The unstoppable rise of geek culture” (Sharp, 2010). This evolution of the term ‘geek’ reflects a changing cultural landscape where everyone can find their place.

Many media stories focusing on geeks examine how this subculture has found acceptance by the mainstream, indicating that while “geeks” may have become “cooler,” mainstream culture has simultaneously become “geekier.” This acceptance of geek culture has led to a proliferation of its aesthetics and themes across various media. The mainstreaming of video games, in particular, has fueled a widespread appeal for fantasy and virtual worlds, evident in the immense popularity of recent film and television series such as HBO’s House of the Dragon, Netflix’s Stranger Things, and Amazon Prime Video’s The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.

Comic book characters, once niche emblems of geek culture, have become central to blockbuster cinema, with recent examples including Marvel’s Spider-Man: Across the Multiverse, DC’s Superman, and Marvel’s The Fantastic Four: First Steps. These cinematic universes have expanded the idea of immersive worlds, appealing to vast global audiences. Furthermore, virtual worlds within modern online games like Epic Games’ Fortnite (which has evolved beyond battle royale into a social hub for concerts and events), Roblox, and various burgeoning metaverse platforms like Decentraland and The Sandbox, offer not merely means of escape but new, interactive ways for people to connect, socialize, and express themselves within persistent digital environments.

The Effects of Video Games on Other Types of Media

Video games in the 1970s and 1980s were often inspired by other forms of media, such as films and literature. E.T., Star Wars, and numerous other games drew inspiration from movies, television shows, and books. This began to change in the 1980s with the development of cartoons based on video games, and continued in the 1990s and 2000s with the emergence of live-action feature films based on video games. These films, such as the Resident Evil series and the Tomb Raider movies, not only expanded the reach of the video game franchises but also influenced the film industry by introducing new narrative and visual styles.

Television

Television programs based on video games have a long history, dating back to the early 1980s with animated series such as Pac-Man, Pole Position, and QBert. The late 1980s saw shows such as The Super Mario Bros. Super Show! and The Legend of Zelda promotes Nintendo games. The 1990s brought Pokémon, which originated as a game for the Nintendo Game Boy and exploded into a global phenomenon with a highly successful television series, a trading card game, numerous movies, and even a musical (Internet Movie Database).

In recent years, the influence of video games on television has reached unprecedented levels, with a “golden age” of adaptations. Critically acclaimed and commercially successful series like HBO’s The Last of Us (2023), Amazon Prime Video’s Fallout (2024), and animated hits such as Netflix’s Arcane (based on League of Legends, 2021) and Netflix’s Cyberpunk: Edgerunners (2022) have demonstrated the rich storytelling potential of game narratives. These adaptations often boast high production values, complex character development, and intricate plots that appeal to both long-time fans and new audiences.

Beyond direct adaptations, the very concept of video games and “geek culture” has become deeply embedded in mainstream television. Shows like The Big Bang Theory (although it has concluded, it popularized “nerd” archetypes) and the continued prevalence of fantasy and sci-fi epics reflect this shift. The proliferation of virtual worlds and expansive narratives, once confined to games like Grand Theft Auto and Halo, now extends across various media. Modern online games, such as Epic Games’ Fortnite and Roblox, as well as emerging metaverse platforms (e.g., Decentraland, The Sandbox), are not just games but social hubs, hosting virtual concerts, brand experiences, and fostering new forms of community interaction that blur the lines between gaming and everyday life.

This growing ubiquity of gaming has also impacted how media consumption is measured and perceived. Nielsen, a leading company in audience measurement, now actively tracks and reports on video game engagement, recognizing it as a significant media category alongside traditional television. This data highlights that gaming is no longer a niche hobby but a pervasive form of entertainment, influencing advertiser decisions and solidifying its place as a core media habit akin to television watching.

Furthermore, the interactivity inherent in video games has had a profound influence on television production. Modern sports broadcasts, for example, frequently employ augmented reality (AR) overlays to display real-time player statistics, tactical analyses, and even virtual graphics directly on the field or court, enhancing the viewer’s understanding and engagement. Companies like Cosm are creating immersive entertainment venues that project live sports and other content onto massive LED domes, offering a “shared reality” experience that blends physical presence with virtual spectacle. Additionally, streaming platforms and live events increasingly incorporate real-time audience interaction through polls, Q&A sessions, and interactive graphics, allowing viewers to influence content or participate directly. This type of innovation can only exist with a public that has come to demand and rely on the kind of dynamic engagement that video games provide.

Film

Video games have profoundly influenced the film industry, transforming their role from a challenging source of adaptations to a vibrant wellspring of cinematic inspiration and technological innovation. While earlier film versions of video games, such as 1995’s Mortal Kombat and 2001’s Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, found some box office success, they often struggled to gain critical acclaim or fully satisfy fans (Box Office Mojo). This narrative has undergone a dramatic shift over the past seventeen years, particularly during the 2010s and 2020s. We are now witnessing a “golden age” for the genre, marked by blockbuster successes like The Super Mario Bros. Movie, which soared to become one of the highest-grossing animated films ever, alongside the popular 2020 and 2022 Sonic the Hedgehog films, Pokémon Detective Pikachu, Uncharted, Five Nights at Freddy’s and A Minecraft Movie. This new wave of adaptations benefits from larger production budgets, more faithful storytelling, and creative teams deeply invested in the original material, allowing these cinematic ventures to resonate widely with diverse audiences.

Beyond direct adaptations, video games have reshaped the film industry in several fundamental ways, notably in marketing and public perception. The sheer scale of production and the immense profitability of major video game titles now frequently rival those of Hollywood blockbusters. Game releases are often promoted with the same intensity as major movie premieres, sometimes even competing directly for public attention. This elevated status has profoundly altered public perception, with video games increasingly recognized as a powerful and legitimate form of narrative entertainment. The staggering revenue generated by the video game industry, which has even surpassed the combined totals of the film and recorded music industries in recent years, underscores its significant economic and cultural influence. The scale of production and profit for video games has become similar to that of cinema. Video games often feature music scores, actors, and directors, in addition to game designers, and the budgets for major games reflect this. Grand Theft Auto IV cost an estimated $100 million to produce (Bowditch, 2008).

Furthermore, the very methods of film production have increasingly adopted tools and methodologies first pioneered in the gaming world. Game engines, such as Epic Games‘ Unreal Engine and Unity Technologies’ Unity, initially designed for developing interactive virtual experiences, are now indispensable in filmmaking. These powerful software platforms facilitate real-time rendering of intricate digital environments, empowering directors and cinematographers to visualize scenes, adjust lighting, and fine-tune camera movements directly on set. This innovative approach was famously employed in productions like Disney’s The Mandalorian, where massive LED walls displayed high-fidelity virtual backgrounds, dramatically reducing the reliance on traditional green screens and enhancing actor immersion within the digital world. Beyond rendering, motion capture technology, refined through years of game development, has become a cornerstone for creating remarkably realistic computer-generated characters and complex action sequences in films, bringing an unprecedented level of authenticity to digital performances. Game engines also significantly enhance pre-visualization, allowing filmmakers to “play through” scenes and experiment with creative choices before principal photography, leading to substantial savings in both time and resources. Even the branching narratives and player-choice elements common in video games have inspired experimental interactive films, exemplified by Netflix’s Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, where viewers actively make decisions that alter the storyline, thereby blurring the traditional boundaries between passive viewing and active participation.

This dynamic and symbiotic relationship continues to evolve, with video games serving not only as a rich source of intellectual property for adaptation but also as a powerful driving force behind technological innovation and the evolution of narrative approaches within the film industry.

Music

Music has been an integral part of video games since the earliest arcade days, evolving dramatically from simple computer beeps constrained by hardware limitations into sophisticated, immersive soundscapes. The advent of consoles like the Nintendo 64, Sega Saturn, and Sony PlayStation in the mid-1990s revolutionized game audio by enabling the use of sampled sound. This breakthrough allowed developers to incorporate recorded music played on physical instruments, moving beyond synthesized tones. This innovation truly blossomed with the music of iconic series such as Final Fantasy, famously scored by Nobuo Uematsu, whose compositions took on the grand, emotional quality of film scores, complete with full orchestral and vocal tracks. This artistic leap proved highly beneficial to the broader music industry, opening new avenues for exposure and employment. Today, renowned composers like Austin Wintory (Journey, Abzû), Lena Raine (Celeste, Guild Wars 2), and Bear McCreary (God of War) are celebrated for their original game scores, reaching vast new audiences. Composing music for video games has become a highly sought-after and profitable career path, leading prestigious institutions such as Berklee College of Music, New York University, and the University of Southern California to establish dedicated programs focusing on video game scoring, where students learn principles akin to those used in film composition, often collaborating with game development students on real projects (Khan, 2010).

Beyond original scores, video games have had a significant impact on the music industry through the licensing of popular songs. Many contemporary artists and rock bands readily allow their previously recorded music to be featured in games, mirroring the inclusion of hit songs on movie soundtracks. This provides artists with licensing fees and, crucially, exposes their music to new generations of potential fans who might not otherwise encounter it. While rhythm games like Rock Band and Guitar Hero were highly influential in promoting bands in the late 2000s, even leading to special releases such as The Beatles: Rock Band, coinciding with remastered albums, the integration of licensed music has evolved. Modern titles across various genres, from sports franchises like MLB: The Show, EA Sports FC (formerly FIFA), and NBA 2K to open-world epics like Grand Theft Auto V (renowned for its diverse in-game radio stations featuring original and licensed music), consistently curate extensive soundtracks of popular contemporary and classic tracks. Sound Shapes, released in 2012, innovated the music video game genre by seamlessly blending platforming gameplay with music creation, allowing players to build levels that simultaneously composed dynamic soundtracks. Its unique approach, featuring musical contributions from professional artists like Beck, Deadmau5, and Jim Guthrie, demonstrated a deeper integration of interactive music, influencing subsequent games to explore more creative and player-driven audio experiences beyond traditional rhythm-matching. This deep integration makes music an integral part of the game’s atmosphere and identity, often leading to songs experiencing a renewed popularity or discovering new fan bases.

Another vibrant phenomenon related to music and video games involves musicians performing and reinterpreting video game music. The trend of bands performing video game covers has continued to flourish, with groups like the popular Japanese ensemble The Black Mages, who specialized in rock versions of Final Fantasy music, maintaining a dedicated following. Orchestras and choruses dedicated to playing well-known video game music, such as the globally touring Video Games Live, continue to draw large crowds, often projecting synchronized gameplay footage and graphics during their performances to create a truly immersive experience (Play Symphony). Furthermore, the rise of streaming platforms has made official game soundtracks and fan-created remixes widely accessible, with many video game scores now garnering millions of streams and even receiving recognition from major awards, solidifying video game music’s place as a significant and respected genre within the broader musical landscape.

Video Games and Education

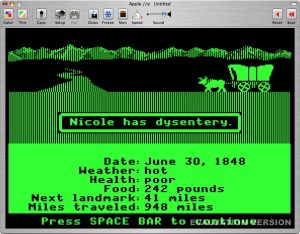

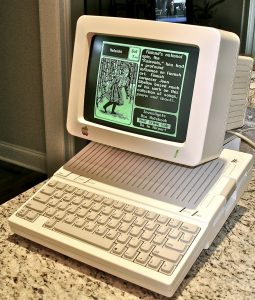

The increasing embrace of video games by educational institutions underscores their mainstream acceptance and growing recognition as valuable learning tools. Decades ago, games like Number Munchers and Word Munchers offered early examples of how interactive digital experiences could foster basic math and grammar skills in children. Oregon Trail, first developed in 1971, became a foundational educational computer game widely used in schools, immersing students in the challenges of 19th-century American westward expansion through resource management and decision-making. Its interactive and often unforgiving gameplay taught valuable lessons about history, geography, and problem-solving, setting a precedent for experiential learning in digital environments. Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, launched in 1985, revolutionized geography education by transforming learning into an engaging detective adventure. This game cleverly integrated real-world geographical facts and cultural information into its mystery-solving mechanics, proving that educational software could be both informative and highly entertaining.

Integrating video games and education has since evolved dramatically, supported by extensive research that consistently highlights the cognitive benefits of video game play, demonstrating improvements in areas such as visual processing, problem-solving, critical thinking, and even “fluid intelligence“—the ability to adapt and solve novel problems without prior knowledge (Feller, 2006). More recent research, including ongoing work by the Office of Naval Research, continues to explore how gaming can enhance information processing speed and fundamental reasoning abilities in adults, noting that frequent gamers often exhibit superior perceptual and cognitive skills.

Modern educational landscapes are now rich with examples of video games and game-inspired approaches. Far beyond early examples, contemporary educational games and gamified learning platforms offer immersive and interactive experiences that seamlessly blend entertainment with core curriculum. Educators now leverage game-based learning to simplify complex subjects, such as math and science, transforming abstract concepts into engaging, hands-on activities where students can experiment in virtual laboratories without real-world consequences. Games like Minecraft: Education Edition enable students to explore and build in interactive environments across various subjects, while Civilization VII immerses learners in historical, cultural, and geopolitical concepts, fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Platforms such as Kahoot! and Quizlet transform traditional quizzes into dynamic, competitive games, providing immediate feedback and fostering a fun, engaging atmosphere that reinforces knowledge. For younger learners, applications like Khan Academy Kids utilize gamified features such as points and badges to enhance literacy and math skills through adaptive, personalized learning paths.

Crucially, these new technologies also revolutionize how teachers and students communicate and collaborate. Many modern educational games are specifically designed for teamwork, requiring players to articulate thoughts, strategize, and coordinate actions in real-time. This active engagement in multiplayer environments naturally hones communication skills, fostering collaboration and social interaction among learners. Beyond specific games, the principles of gamification—incorporating elements like points, badges, leaderboards, and progress bars into learning activities—motivate students and provide clear visual indicators of their progress, making the learning journey feel more manageable and rewarding. Teachers can effectively use these systems to track individual and group achievements, encouraging healthy competition and a strong sense of accomplishment.

The validation of video games in education extends beyond traditional classrooms. Youth organizations, recognizing the appeal and skill-building potential of gaming, have integrated it into their programs. The rise of scholastic and collegiate esports is a prime example, with high schools and universities worldwide establishing competitive gaming teams. These programs not only offer new avenues for student engagement and scholarships but also cultivate crucial 21st-century skills such as teamwork, communication, strategic thinking, and digital literacy, often linking directly to STEM fields and potential career paths in the rapidly expanding esports industry.

Furthermore, immersive technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) are being increasingly integrated into educational gaming. VR can transport students to entirely different worlds, whether it’s ancient Rome or the intricate interior of a human cell, offering a deeply immersive learning experience that significantly enhances retention. AR, conversely, overlays digital information onto the real world, allowing students to interact with 3D models of the solar system on a classroom desk or bring historical figures to life within their physical learning space. These technologies not only make learning more engaging but also provide unique opportunities for interactive discussions and shared discoveries, fundamentally changing the dynamic between educators and learners.

Government bodies and public sectors have also actively promoted the educational potential of video games. Initiatives like iCivics offer free, interactive games designed to teach students in grades K-12 civics and government concepts. The Federal Games Guild serves as a community of practice for U.S. federal agencies interested in leveraging games for various initiatives, including public education and outreach. Moreover, the military continues to be a significant adopter of advanced gaming technology for training. Highly sophisticated military training simulators utilize cutting-edge game engines and virtual reality to create realistic, immersive environments where recruits can practice tactical decision-making, engage in combat scenarios, and develop cultural awareness in a safe and repeatable setting. These simulators are continuously updated to reflect real-world conditions and leverage the latest advancements in game development. The U.S. Army and Army National Guard have also effectively used video games as engaging recruiting tools, offering potential service members a virtual glimpse into military life (Associated Press, 2003).

The widespread and increasing adoption of video games by diverse educational institutions and cultural authorities signifies a profound shift in perception. While some individuals may still harbor skepticism about the societal benefits of video games, their integration into formal and informal learning environments unequivocally validates their capacity to provide meaningful educational experiences and exert a powerful, positive cultural influence. The continuous evolution of video game technology promises even more sophisticated and interconnected learning experiences in the future, further blurring the lines between play and education.

Video Games as Art

While video games have long been universally accepted as a prominent form of media, a significant and evolving debate has centered on whether they truly constitute a form of art. Historically, well-known film critics, such as Roger Ebert, have famously argued that “video games can never be art,” often framing them primarily as exercises in competition rather than experiences designed to evoke profound emotion or aesthetic appreciation (Ebert, 2010).

However, Ebert’s remarks, though influential at the time, sparked a widespread outcry from both video gamers and developers, who pointed to a growing body of interactive experiences that defied such narrow definitions. Games like Flower, which invites players to control the gentle flow of flower petals through the wind, intentionally eschew traditional plots and characters to focus on the player’s interaction with the serene landscape and the emotional resonance of the gameplay (That Game Company). Similarly, the imaginative Katamari series, first released in 2004, built its core around the whimsical act of creation, tasking players with rolling a sticky ball to accumulate a massive clump of objects, ultimately forming a new star.

In the years since, the artistic ambition and sophistication of video games have soared, further challenging and essentially refuting the notion that they cannot be art. Modern titles frequently demonstrate breathtaking visual design, intricate soundscapes, and profound narrative depth that rival traditional artistic mediums. Games such as Journey are widely celebrated for their evocative visuals, minimalist storytelling, and powerful emotional impact, often described as interactive poems. What Remains of Edith Finch pushes the boundaries of narrative, using unique gameplay mechanics to explore themes of family, memory, and loss with striking originality. Even expansive, critically acclaimed titles like Elden Ring showcase unparalleled world-building, implicit storytelling, and environmental artistry that invite deep interpretation and appreciation. The visual splendor of games like Gris, with its stunning watercolor aesthetics and exploration of grief through abstract imagery, further exemplifies the medium’s capacity for artistic expression.

Once dismissed as a mindless pastime, video games are now regularly subjects of serious critical analysis and cultural commentary in prestigious publications such as The New Yorker and The New York Times, reflecting a broader societal recognition of their cultural significance (Fisher, 2010). The development of increasingly complex and emotionally resonant musical scores, often performed by full orchestras, and the continued evolution of techniques like machinima (filmmaking within a real-time 3D environment, usually a video game) have further blurred the boundaries between video games and other established forms of media. While a lingering debate about their artistic merits may persist in some corners, the undeniable contributions of video games to modern artistic culture, through their innovative design, immersive storytelling, and profound emotional resonance, have firmly established them as a powerful and evolving art form.