10.6 Blurring the Boundaries Between Video Games, Information, Entertainment, and Communication

Early video games had basic goals and set rules of play. As games have evolved in complexity, they have enabled new options and an expanded understanding of what constitutes a game. At the same time, the aesthetics and design of game culture have infiltrated tools and entertainment phenomena. This has resulted in a blurring of the lines between games and other forms of communication, leading to the creation of new ways to combine information, entertainment, and communication.

Video Games as Mass Communication

Video games have undergone a remarkable transformation, evolving from niche entertainment into a formidable segment of mass communication that rivals and often surpasses traditional media in scale and influence. This growth has been propelled by significant advancements in graphic capabilities, as exemplified by groundbreaking titles like Wolfenstein 3D and Street Fighter, which broadened their appeal to a mainstream audience. Modern video game consoles are no longer just gaming machines, but sophisticated media content devices. The PlayStation 5, for instance, includes an Ultra HD Blu-ray player, and the Xbox 360 was notably marketed as an all-encompassing entertainment hub.

The cultural impact of video games is further evident in the celebrity-like status of many popular video game characters, who are instantly recognizable globally. Beyond character popularity, video games have become a significant and growing venue for advertising. Companies like Anzu specialize in embedding advertisements within games, a strategy famously adopted by Barack Obama’s presidential campaign, which utilized in-game ads to reach voters.

Furthermore, video games serve as vibrant centers for online communities. Titles such as World of Warcraft, Halo, and Call of Duty have long fostered massive online social spaces. More recent examples, such as Final Fantasy XIV, are renowned for their welcoming communities, while Elder Scrolls Online offers an immersive world ripe for social interaction. The battle royale genre, encompassing games like Fortnite, Apex Legends, and PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), boasts enormous player bases and strong community engagement driven by frequent updates and cooperative gameplay. Similarly, multiplayer online shooters like Overwatch 2, Valorant, and Counter-Strike 2 thrive on their competitive scenes and passionate fanbases. Even sandbox games like Minecraft and user-generated content platforms like Roblox, alongside competitive MOBA League of Legends and the unique Rocket League, play a pivotal role in fostering creativity, collaboration, and extensive online communities.

Economically, video games are an incredibly profitable part of popular culture, often outperforming films. For perspective, while Avengers: Endgame famously took five days to reach $1 billion in revenue, global video game sales have consistently eclipsed U.S. domestic movie box office receipts since 1985, underscoring their immense financial power. This dominance is intrinsically linked to the role of video games as a significant element of media synergy and convergence. This convergence is evident in integrated ecosystems like Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe and the Star Wars franchise, where movies, TV shows, comics, and merchandise are intricately interwoven. Content distribution also spans multiple platforms, from Netflix Originals reaching various channels to Amazon Prime Video integrating with other Amazon services. Social media is heavily utilized, with TikTok challenges and Instagram Live Shopping providing new avenues for brand promotion. Within the gaming industry, convergence is evident in successful game-to-film adaptations, such as The Witcher and Uncharted, as well as in interactive storytelling and the immersive experiences offered by virtual and augmented reality in both gaming and live entertainment.

The legal landscape also acknowledges video games’ status as a form of mass communication; in the landmark 2011 case Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, the Supreme Court affirmed First Amendment protection for video games, striking down a law that restricted the sale of violent games. Justice Scalia famously stated that “Disgust is not a valid basis for restricting expression.”

Supporting this ecosystem are platforms like Twitch, founded in 2011 and later acquired by Amazon for $970 million, which now boasts 35 million daily viewers, cementing its role as a premier live streaming service for gaming. Similarly, Minecraft has profoundly shaped YouTube’s content landscape, popularizing “Let’s Play” videos, inspiring countless Minecraft-focused channels, and fostering creative content and community building, ultimately influencing other gaming genres on the platform. Beyond organized platforms, active discussion boards and the widespread phenomenon of “mods” (modifications) for games like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, Grand Theft Auto V, Minecraft, RimWorld, and The Sims demonstrate the deep engagement and creative contributions of gaming communities, further blurring the lines between content creators and consumers in this pervasive form of mass communication.

Video Games and the Social World of Sports

The meteoric rise of esports further solidifies the position of video games. This competitive gaming phenomenon has evolved from a niche hobby into a global industry, driven by technological advancements such as high-speed internet and streaming platforms, increased accessibility of gaming hardware, and professionalization through leagues and tournaments. Expanded media coverage and passionate fan engagement have transformed esports into a significant economic driver with a profound cultural influence, challenging stereotypes about gamers.

Video games have evolved in complexity and flexibility to the point that they offer new forms of social interaction. For instance, compare video games to physical sports. Most of the abstract reasons for involvement in sports—such as teamwork, problem-solving, and leadership—also motivate people to play online video games, which often involve team interaction. Parents, coaches, and fans frequently praise sports as a social platform where people can acquire new skills. Amateur sports teams offer a vital means of socialization and communication for many people, enabling individuals from diverse genders, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds to find a common platform for interaction. Video games, with their similar capacities, offer a more inclusive platform for socializing. They do not exclude most individuals who are socially or physically challenged. Although competitive endeavors of any sort inevitably create opportunities for negative communication, the social platform allows people of different genders, races, and nationalities to play on equal footing —a feat, albeit different, if not improbable, to achieve in the physical realm.

Virtual Worlds and Societal Interaction: The Potential and Excitement

Massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) have long allowed players to pursue an unprecedented variety of goals beyond traditional questing and combat. These virtual environments inherently foster the development of complex social, cultural, and economic systems, transforming games from solitary activities into vibrant, parallel virtual communities (Zaphiris et al., 2008). In this respect, modern MMORPGs function as a compelling hybrid of social media and interactive entertainment. A player might choose to forgo the prescribed goals of a game entirely, instead spending their time engaging in social areas, interacting with other avatars, participating in player-run events, or even running virtual businesses. At such a point, the distinction between “playing a game” and engaging in a form of social media becomes remarkably thin.

This blurring of lines is even more pronounced in dedicated virtual worlds and metaverse platforms such as the pioneering Second Life, alongside newer decentralized platforms like Decentraland, The Sandbox, and the immensely popular Roblox. In these environments, users create highly customizable avatars to represent themselves, then explore vast digital landscapes and actively participate in their evolving cultures. Second Life, for instance, differentiates itself from traditional MMORPGs by emphasizing user freedom and ownership. While its interface may resemble an MMORPG, its core tenets revolve around creativity and intellectual property. Users are granted extensive freedom to create anything from social spaces and nightclubs to businesses and entirely new games within the world. Crucially, residents retain intellectual property rights over their in-world creations, fostering a unique creator economy. Similarly, platforms like Decentraland and The Sandbox leverage blockchain technology and NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) to enable actual digital ownership of virtual land, assets, and user-generated content, allowing for the exchange of real-world economic value within these digital realms. Roblox, with its vast ecosystem of user-created games and experiences, further exemplifies this trend, attracting millions of daily active users who are not just players but also creators and entrepreneurs within its virtual economy.

Regardless of their specific classification, these virtual worlds heavily rely on the aesthetics and design principles of video games, leveraging immersive environments and interactive elements to facilitate rich social interaction. These virtual societies significantly expand communication opportunities, enabling the relay of information and experiences in ways that traditional media cannot equal. Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) technologies are increasingly integrated into educational settings, offering unique possibilities for immersive simulations, collaborative learning, and global interaction. A class on architecture could lead students through a three-dimensional recreation of a Gothic cathedral in VR, a history class might utilize an interactive battlefield simulation to explain the mechanics of a famous battle, or a physics class could use AR overlays to demonstrate complex principles tangibly.

Beyond education, virtual worlds and immersive technologies provide a range of other societal benefits. Since 2007, specialists have developed virtual-reality simulations to help individuals with social communication challenges, such as those with autism spectrum disorder, navigate complex social situations more effectively. These simulations enable users to create avatars and practice scenarios, such as job interviews or everyday conversations, in a safe and controlled environment. Specialists can adjust the complexity of interactions, and users can replay their performances, receiving real-time feedback to understand nonverbal cues better and adapt to changing social dynamics (University of Texas at Dallas News Center, 2008). This direct influence of video game design, particularly the creation of avatars and the ability to practice and refine actions, offers a powerful therapeutic tool. The continuous evolution of these virtual environments promises even more sophisticated and interconnected applications, further blurring the lines between digital play and meaningful real-world impact.

Social Media and Games

The integration of video games into social media platforms has profoundly influenced communication and community building. This symbiotic relationship has evolved significantly, pushing the boundaries of how and where people engage with games and with each other.

Facebook Instant Games: A Case Study in Platform Integration

In 2016, Facebook (now Meta) launched Facebook Instant Games, an HTML5-based cross-platform gaming experience integrated directly into Messenger and the Feed. This initiative aimed to lower the barrier to entry for casual gaming, allowing users to discover, share, and play games without needing to install separate applications. Initially, it offered a social experience with score-based games, leaderboards, and group thread conversations within Messenger. While it has seen its share of “starts and stops” and faced challenges with monetization on iOS for some time, Instant Games continue to exist within the Facebook platform, with ongoing efforts to enhance developer support and monetization options. This demonstrates a persistent attempt by major social media companies to leverage casual gaming for user engagement and retention.

The phenomenon described by Walker (2010) regarding “coupling games with social media sites,” which pushes the influence of video games to “unprecedented levels,” remains even more relevant today. While Facebook Instant Games focuses on direct gameplay, the broader impact extends to how social media platforms serve as vital hubs for gaming content, discussions, and community formation.

Dedicated Social Networking for Gamers: Beyond General Platforms

The increasing popularity of video games has indeed led to the emergence and growth of numerous social networking websites and platforms specifically catering to both hardcore and casual gamers. These platforms recognize that gamers often seek connections beyond the confines of a specific game and desire dedicated spaces to discuss their passion, find teammates, and even form personal relationships.

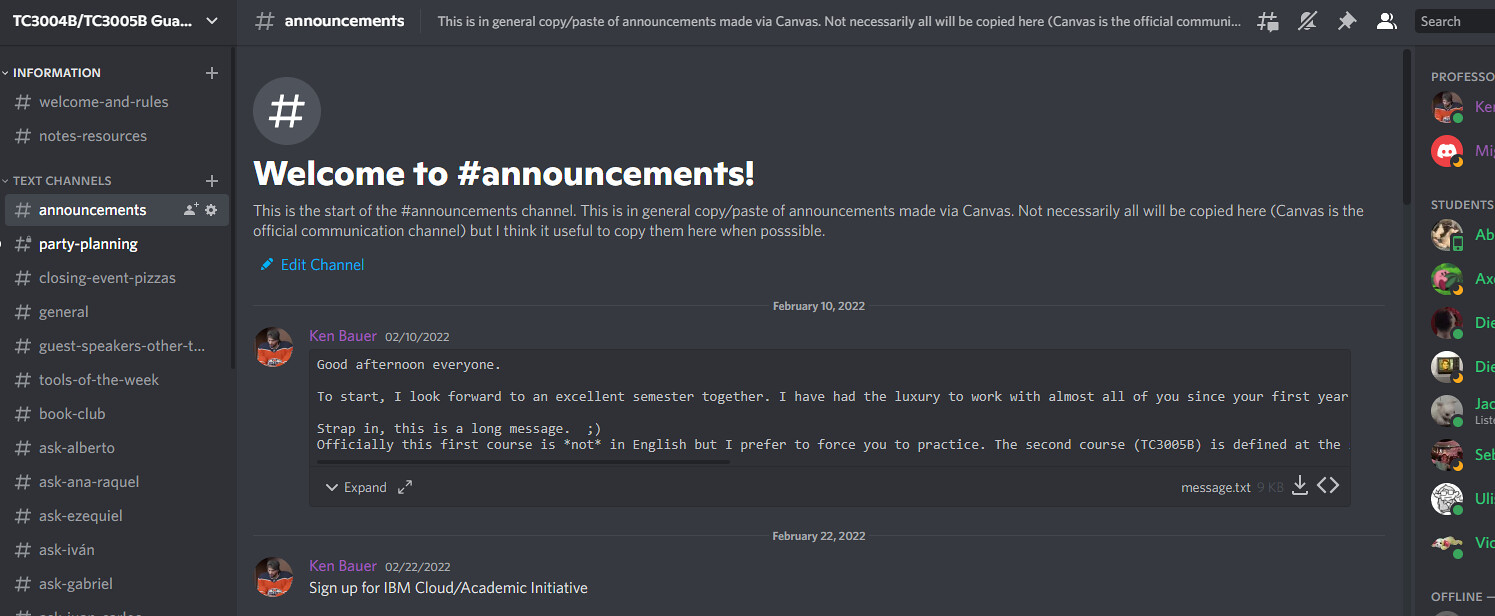

Today, the landscape of social networking for gamers is dominated by comprehensive and dynamic platforms that offer a multitude of features beyond simple dating or general discussion. Discord is arguably the most prominent and widely used platform for gamers, offering robust voice, video, and text communication. Users can create or join servers dedicated to specific games, communities, or interests, making it ideal for team coordination, community events, and casual chat. Twitch, a leading live-streaming platform, allows gamers to broadcast their gameplay, interact with viewers in real-time through chat, and build a community around their content. It’s a significant hub for esports, game promotion, and direct engagement between streamers and their audience.

Reddit, with its numerous “subreddits” dedicated to virtually every game imaginable, serves as a massive forum for discussions, news, memes, and community-driven content. Gamers use it to find tips, share experiences, and connect with niche communities. The Steam Community, beyond being a digital storefront, offers extensive features like forums, user reviews, guides, workshops for user-created content, and integrated chat, allowing players to connect directly within the ecosystem where they play many of their PC games. YouTube Gaming, although part of a broader video platform, is immense, hosting numerous gameplay videos, reviews, tutorials, esports highlights, and streams, with many gamers following content creators and engaging through comments and subscriptions. Other apps like GameTree aim to connect gamers based on compatibility, using personality tests and gaming preferences to help users find ideal gaming buddies and even romantic partners, focusing on personalized matchmaking and fostering meaningful connections.

In essence, social media’s influence on gaming has moved beyond simple integration to creating entirely new ecosystems where gaming communities thrive, content is shared, and social connections are formed, sometimes even leading to real-world relationships. The constant evolution of technology and user behavior will undoubtedly continue to reshape this dynamic intersection of social media and games.

Mobile Phones and Gaming

The emergence of Internet-enabled mobile phones revolutionized gaming, transforming it from a niche activity into a pervasive form of entertainment and social interaction. What began as a shift from computer to phone platforms has blossomed into a sophisticated ecosystem where mobile games profoundly shape how people connect, communicate, and express themselves.

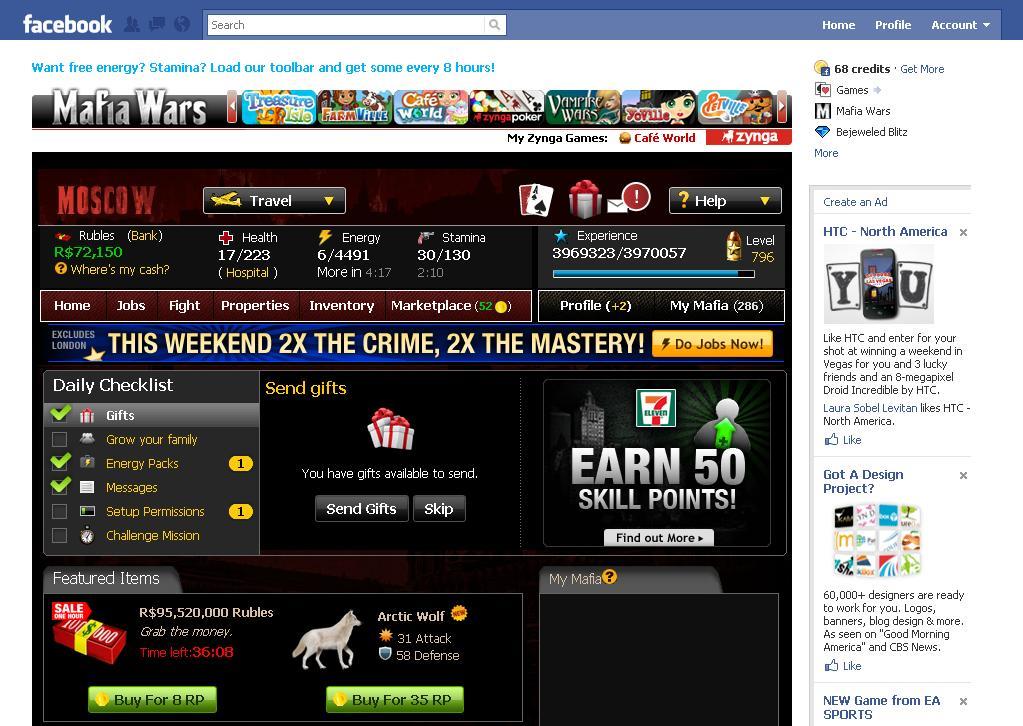

Early mobile social games, such as Zynga‘s FarmVille and Mafia Wars, demonstrated the power of integrating casual games with nascent mobile capabilities. FarmVille, in particular, leveraged social network features for virality, with players sending virtual gifts and collaborating on farm-building tasks. Mafia Wars, which also had a significant presence on Facebook before its mobile iteration and eventual cancellation, allowed players to manage simulated criminal empires and engage in competitive activities. This early innovation led to more than just a platform shift. It laid the groundwork for mobile gaming to become a primary means of social interaction. The ease of access, the “always-on” nature of mobile devices, and the intuitive touch interfaces made games accessible to a far broader audience than traditional PC or console gaming.

The idea that adding games to phones creates “a new language that people can use to communicate with each other” has proven incredibly prescient. Before social media, the notion of transmitting a spat or a romantic connection through a game was conceptual, but today, it’s commonplace. The sheer volume of virtual gifts exchanged in FarmVille during Valentine’s Day 2010 (over 220 million) was an early indicator of this powerful social dimension (Ingram, 2010). During events like the annual Winterfest in Fortnite, players often exchange thousands of gifts, which are primarily cosmetic items like outfits, emotes, and virtual currency. The social dimension is crucial: the act of gifting is not just about the item itself, but about strengthening friendships and celebrating holidays within the game’s community. The feature allows players to directly interact and show appreciation, proving that social gestures in a virtual world are still a powerful driver of engagement, much like the early days of FarmVille.

More recently, mobile games have integrated sophisticated social features that facilitate diverse forms of communication and interaction. Modern multiplayer mobile games, ranging from competitive titles like Mobile Legends: Bang Bang and Call of Duty: Mobile to casual cooperative experiences, now feature robust in-game text and voice chat. This allows for real-time strategy, friendly banter, and the development of strong social bonds among players, whether they are friends in real life or met within the game. Many mobile games are also built around guild or clan systems, where players form persistent groups to collaborate on objectives, compete against other groups, and share resources. These in-game social structures foster a sense of belonging and teamwork, often leading to extensive out-of-game communication on platforms like Discord.

The prevalence of cooperative and Player-versus-Player (PvP) modes inherently encourages direct interaction. Whether it’s helping a friend overcome a challenging level or engaging in a friendly rivalry on a leaderboard, these interactions fuel a broad spectrum of emotions, from generosity and camaraderie to intense competition and even playful aggression. Players routinely send in-game items, resources, or even “lives” to friends, not just as a game mechanic but as a genuine gesture of support, gratitude, or even a subtle form of communication.

Furthermore, mobile games often integrate with major social media platforms, such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok, allowing players to share achievements, invite friends, and spectate gameplay easily. This integration extends the game’s social reach beyond its ecosystem. The rise of mobile esports and game streaming on platforms like Twitch and YouTube has further transformed how players interact, as spectators can chat directly with streamers and other viewers, forming vibrant communities around shared interests and favorite content creators.

In contemporary mobile gaming, the expression of competition, aggression, hostility, generosity, and general friendliness is not just given “new means of expression”. Still, it has become deeply embedded in the core gameplay loop and the broader social fabric surrounding these titles. Mobile phones have unequivocally made gaming a common, indeed ubiquitous, means of social interaction, fundamentally reshaping how individuals connect in the digital age.

Video Games and Their Messages

Beyond entertainment, video games have evolved into powerful interactive mediums for conveying specific messages, exploring complex social issues, and engaging players with thought-provoking political and ethical dilemmas. These “serious games,” often created by independent developers, advocacy groups, or even mainstream organizations, push the boundaries of what video games can communicate.

Sometimes, independent developers or small studios create impactful, often low-budget, games to convey a specific point or critique. Molleindustria, for example, remains a prominent collective known for producing a range of critical games that blend satire with social commentary. Their titles, such as Oiligarchy, where players manage an oil-drilling business and navigate corruption to maximize profits, and Faith Fighter, which satirically depicts religious icons in combat, exemplify how games can deconstruct complex societal structures and beliefs (Industria). Other games of theirs include The New York Times Simulator, The McDonalds Videogame, Queer Power, and many more.

The modern video game landscape includes titles that feature substantial content designed to inform players about current events and complex global phenomena. The field of “newsgames” or “journalism games” has expanded considerably, immersing players in scenarios that help them understand the forces at work behind real-world issues, from geopolitical conflicts to economic crises. For instance, the indie game Papers, Please, where players act as a border agent in a fictional dystopian state, forces them to confront difficult ethical decisions and the complexities of political systems.

Similarly, games designed for civic engagement and education demonstrate how interactive experiences can inform players about specific policy issues and inspire action. iCivics, a non-profit founded by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, offers a range of free-to-play games where players can run a law firm that specializes in constitutional rights, draft legislation, or manage a presidential campaign. Furthermore, titles like Alba: A Wildlife Adventure teach players about sustainability and environmental issues as they clean up a Mediterranean island and restore its natural habitats. Publishers and developers are increasingly leveraging the interactive nature of games to convey information in uniquely engaging ways.

Political satire delivered through video games offers a distinct advantage: it allows the player to effectively “play out” a satirical joke to its logical conclusion, exploring the entire scope and implications of the commentary through direct interaction. This engagement contrasts sharply with passive forms of media consumption.

The concept of “advocacy games” has matured significantly. These games engage players with an interactive political or social message, often proving more impactful than traditional media advertisements. Mainstream non-profit and advocacy groups widely utilize video games to convey their messages. For instance, PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) has a long history of creating parody games to highlight concerns about animal cruelty, such as their Thanksgiving-themed parody of the popular Cooking Mama series, designed to criticize meat consumption (Sliwinski, 2008). This practice continues today, with PETA regularly releasing new games that comment on various animal welfare issues, often targeting widespread cultural phenomena or major game releases with their satirical takes.

The use of games for advocacy extends beyond satire. Organizations develop “serious games” or “games for change” to raise awareness about humanitarian crises, environmental issues, mental health challenges, and historical events. These games can foster empathy, encourage critical thinking, and even facilitate real-world action by providing players with actionable information or connections to relevant causes. They transform abstract concepts into tangible, interactive experiences, allowing players to grasp the complexities of an issue by experiencing it firsthand or making consequential decisions within a simulated environment.

While these message-driven games may not always compete with blockbuster series like The Legend of Zelda in terms of production budget or mainstream popularity, they are crucial in pushing the boundaries of the video game as a form of media. Just as political pamphlets played a significant role as a primary source of information and a platform for political discourse during historical periods, such as the American Revolution, video games are increasingly serving a similar informational and discursive function in the digital age. They offer a unique avenue for expressing complex ideas, challenging perspectives, and fostering a deeper, more interactive engagement with social, political, and ethical messages.