11.4 The Effects of the Internet and Globalization on Popular Culture and Interpersonal Communication

The name World Wide Web encapsulates its essence. The Internet has shattered communication barriers between cultures, a feat that earlier generations could only dream of. Today, individuals can access a multitude of news services from around the world, understanding their content with the aid of tools like Google Translate. This not only facilitates the spread of American culture but also empowers smaller nations to export their own culture, news, entertainment, and even propaganda at a fraction of the cost.

The Internet, a catalyst for globalization, has significantly reduced the impact of geographical distances. It enables the outsourcing of jobs, such as software development, to teams in distant countries like India. Despite the thousands of miles that separate them, communication is seamless, thanks to online tools such as email, instant messaging, and video conferencing. The most challenging aspect of setting up an international video conference online is often just figuring out the time difference.

Electronic Media and the Globalization of Culture

The rise of globalization has not only spurred economic growth but also democratized access to information. The Internet, at its core, dismantles economic and cultural barriers, fostering communication between countries. This is evident in the form of easy access to foreign newspapers or the ability of individuals in previously closed countries to share their experiences with the world at a minimal cost.

TV, especially satellite TV, has proliferated American cultural norms via the media it exports to global audiences (Arango, 2008). American popular culture remains one of the country’s most crucial exports.

At the Eisenhower Fellowship Conference in Singapore in 2005, U.S. ambassador Frank Lavin gave a defense of American culture that differed somewhat from previous arguments. It would not be all Starbucks, MTV, or Baywatch, he said, because American culture is more diverse than that. Instead, he said that “America is a nation of immigrants,” and asked, “When Mel Gibson or Jackie Chan come to the United States to produce a movie, whose culture is being exported (Lavin, 2005)?” This idea of a truly globalized culture—one in which a person can distribute content just as easily as receive it—now has the potential to be realized through the Internet. While some political and social barriers remain, from a technological standpoint, there is nothing to stop the two-way flow of information and culture across the globe.

Don’t Be Evil: How Google’s Stance on Censorship Tested Globalization

The scarcity of artistic resources, the time lag in transmission to a foreign country, and censorship by the host government can all impede the transmission of entertainment and culture. China provides a valuable example of the ways the Internet has helped to overcome (or highlight) all three of these hurdles.

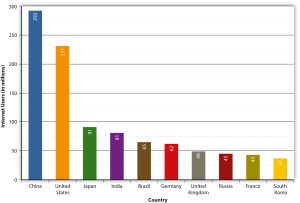

China, as the world’s most populous country and one of its leading economic powers, has considerable influence on the Internet. Additionally, a single political party governs the country and employs extensive censorship to maintain its control. Despite the open nature of the Internet, China has a highly well-connected population—with 22.5 percent (roughly 300 million people, or the population of the entire United States) of the country online as of 2008 (Google, 2010)—China has been a case study in how the Internet makes resistance to globalization increasingly complex.

On January 21, 2010, Hillary Clinton gave a speech in Washington, DC, saying, “We stand for a single Internet where all of humanity has equal access to knowledge and ideas (Ryan & Halper, 2010).” That same month, Google decided to stop censoring search results on Google.cn, its Chinese-language search engine, due to a serious cyberattack on the company originating in China. In addition, Google stated that if it could not agree with the Chinese government regarding the censorship of search results, it would withdraw from China altogether. Because Google had complied (albeit uneasily) with the Chinese government in the past, this policy change signified a significant reversal. Withdrawing from one of the largest and fastest-growing markets in the world is shocking, coming from a company that has been aggressively expanding into foreign markets. This move highlights the fundamental tension between China’s censorship policy and Google’s core values. Google’s company motto, “Don’t be evil,” had long been at odds with its decision to censor search results in China. Google’s compliance with the Chinese government did not help it make inroads into the Chinese Internet search market, although Google held about a quarter of the market share in China; most of the search traffic, however, went to the tightly controlled Chinese search engine, Baidu. However, Google’s departure from China would be a blow to anti-government forces in the country. Since Baidu has a closer relationship with the Chinese government, political dissidents tend to use Google’s Gmail, which uses encrypted servers based in the United States. Google’s threat to withdraw from China raises the possibility that globalization could indeed hit roadblocks due to the ways that foreign governments may choose to censor the Internet.

Internet-Only Sources

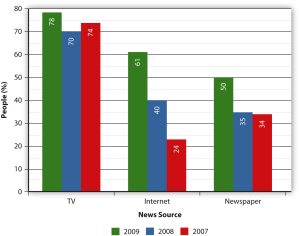

The Internet overtook print media as a primary source of information for national and international news in the U.S. in 2008. This shift in news consumption has significant implications for the media industry and the public. Television remains far in the lead, but especially among younger demographics, the Internet is quickly catching up as a source of news, with 40 percent of the public receiving their news from the Internet (Pew Research Center, 2008). Many legacy news organizations have established websites, although community newspapers tend to engage with online platforms less frequently. Even as news organizations adapt to their shrinking markets, they must contend with another modern competitor: online-only news sources.

The conventional argument claims that the anonymity and the echo chamber of the Internet undermine worthwhile news reporting, especially for expensive topics to cover. However, as the Internet has become a primary news source for an increasing number of people, new media outlets—publications that exist entirely online—have begun to emerge.

In 2006, two reporters for the Washington Post, John F. Harris and Jim VandeHei, left the newspaper to start a politically centered website called Politico. Rather than simply repeating the day’s news in a blog, they decided to start a journalistically viable online news organization. The site has over 6,000,000 unique monthly visitors and approximately 100 staff members, and now features a Politico reporter on almost every White House trip (Wolff, 2009).

Far from being a collection of amateurs trying to make it big on the Internet, Politico’s senior White House correspondent is Mike Allen, who previously wrote for The New York Times, Washington Post, and Time. His daily Playbook column appears at around 7 a.m. each morning and is read by much of the politically centered media. The various ways Politico reaches out to its supporters—through blogs, Twitter feeds, regular news articles, and now even a print edition—illustrate how media convergence has occurred within the Internet itself. The interactive nature of its services and the active comment boards on the site also show how the media have become a two-way street: more of a public forum than a straight news service.

“Live” From New York…

Entertainment programs have also found ways to provide quality content on the Internet, however. Saturday Night Live (SNL) has built an entire entertainment model around its broadcast time slot. Every weekend, around 11:40 p.m. on Saturday, someone interrupts a skit, turns toward the camera, shouts “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!” and the band starts playing. Yet the show’s sketch comedy style also seems to lend itself to the watch-anytime convenience of the Internet. The program releases clips of its sketches and Weekend Update news parody shortly after broadcast on its YouTube channel. The online TV service Hulu carries a full eight episodes of SNL at any given time, with regular 3.5-minute commercial breaks replaced by Hulu-specific minute-long advertisements. The time listed for an SNL episode on Hulu lasts just over an hour, a full half-hour less than the time it takes to watch it live on Saturday night.

Hulu calls its product “online premium video,” primarily because of its desire to avoid amateur content posted on YouTube in favor of courting partnerships with large media organizations. Although many networks, such as NBC and Comedy Central, stream video on their websites, Hulu builds its business by offering a legal way to access all these shows on the same site; a user can switch from South Park to SNL with a single click, rather than having to navigate to a different website.

Premium Online Video Content

Hulu’s success indicates a high demand among Internet users for a wide variety of content, collected and packaged in one easy-to-use interface. The Associated Press rated Hulu as the Website of the Year (Coyle, 2008) and even received an Emmy nomination for a commercial featuring Alec Baldwin and Tina Fey, the stars of the NBC comedy 30 Rock (Neil, 2009). Hulu’s success did not resemble that of the typical dot-com underdog startup, however. In its infancy, it brought together two of the world’s giant media companies, News Corporation and NBC Universal. It made logical sense for these companies to collaborate on monetizing content that others had pirated on YouTube. In December 2005, the video “Lazy Sunday,” an SNL digital short featuring Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell, went viral, garnering over 5,000,000 views on YouTube before February 2006, when NBC demanded that YouTube remove the video (Biggs, 2006). NBC later posted the video on Hulu, where it could sell advertising, as it did not have a deal with YouTube at the time.

Hulu allows users to break free from programming models controlled by broadcast and cable TV providers, choosing freely which shows to watch and when to watch them. This seems to work exceptionally well for cult programs that broadcasters no longer air on TV. In 2008, the show Arrested Development, which was canceled in 2006 after repeated time slot shifts, was Hulu’s second-most-popular program.

Hulu has leveled the playing field for some shows that have struggled to find an audience through traditional means. 30 Rock, much like Arrested Development, suffered from a lack of viewers in its early years. In 2008, New York Magazine described the show as a “fragile suckling that critics coddle but that America never quite warms up to (Sternbergh, 2008).” However, even as 30 Rock shifted time slots mid-season, its viewer base continued to grow through its partnership with Hulu. The nontraditional media approach of NBC’s programming culminated in October 2008, when NBC decided to launch the new season of 30 Rock on Hulu a whole week before it was broadcast over the airwaves (Wortham, 2008). Hulu’s strategy of providing premium online content appears to have paid off: As of March 2011, Hulu had generated 143,673,000 viewing sessions, serving more than 27 million unique visitors, according to Nielsen (ComScore, 2011).

Unlike other “premium” services, Hulu does not charge for its content; instead, the word premium in its slogan seems to imply that it could charge for content if it wanted to. Other platforms, like Sony’s PlayStation 3, block Hulu for this very reason—Sony’s online store sells the products that Hulu gives away for free. However, Hulu has considered moving to a paid subscription model that would allow users to access its entire back catalog of shows. Like many other fledgling web enterprises, Hulu seeks to establish reliable revenue streams to avoid the fate of many companies that folded during the dot-com crash (Sandoval, 2009).

Like Politico, Hulu has packaged professionally produced content into an on-demand web service, eliminating the traditional constraints of media. Just as users can comment on Politico articles (and now, on most newspapers’ articles), they can rate Hulu videos, and Hulu will take this into account. Even when users do not produce the content themselves, they still want this same “two-way street” service.

|

Rank |

Parent |

Total Streams (in Millions) |

Unique Viewers (in Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

YouTube |

6,622,374 |

112,642 |

|

2 |

Hulu |

635,546 |

15,256 |

|

3 |

Yahoo! |

221,355 |

26,081 |

|

4 |

MSN |

179,741 |

15,645 |

|

5 |

Turner |

137,311 |

5,343 |

|

6 |

MTV Networks |

131,077 |

5,949 |

|

7 |

ABC TV |

128,510 |

5,049 |

|

8 |

Fox Interactive |

124,513 |

11,450 |

|

9 |

Nickelodeon |

117,057 |

5,004 |

|

10 |

Megavideo |

115,089 |

3,654 |

The Role of the Internet in Social Alienation

As they developed, it became quickly apparent that the Internet generation did not typically suffer from perpetual loneliness. After all, the generation raised on instant messaging invented Facebook. As detailed earlier in the chapter, Facebook began as a service limited to college students—a requirement that practically excluded older participants. As a social tool and a reflection of the way younger people now connect online, Facebook has provided a comprehensive model for the Internet’s impact on social skills, particularly on education.

A study by the Michigan State University Department of Telecommunication, Information Studies, and Media has shown that college-age Facebook users connect with offline friends twice as often as they connect with purely online “friends (Ellison, et. al., 2007).” The study found that 90% of participants identified high school friends, classmates, and other acquaintances as the top three groups of people Facebook directed them toward.

However, as Facebook began to grow, users’ networks of friends grew exponentially, and the networking feature became increasingly unwieldy from a privacy perspective. In 2009, Facebook discontinued regional networks over concerns that networks consisting of millions of people were “no longer the best way for you to control your privacy (Zuckerberg, 2009).” Where privacy controls once consisted of allowing everyone at one’s college access to specific information, Facebook now allows only three levels: friends, friends of friends, and everyone.

Meetup: Meeting Up “IRL”

The Internet has become a hub of activity for a wide range of people. In 2002, Scott Heiferman started Meetup based on the “simple idea of using the Internet to get people off the Internet (Heiferman, 2009).” Meetup does not attempt to foster global interaction and collaboration like Usenet; instead, it provides a platform that allows people to organize local events (COVID-19 necessitated they add the addition of the ability to host online events, which remains to this day). People can search for Meetups for a variety of social reasons, including political, athletic, spiritual, musical, or philosophical interests. Essentially, the service (which charges a small fee to Meetup organizers) separates itself from other social networking sites by encouraging real-life interaction. Whereas a member of a Facebook group may never see or interact with fellow members, Meetup keeps track of the (self-reported) real-life activity of its groups. Ideally, people like to join groups with more activity. Despite the amount of time these groups spend together on or off the Internet, one group of people undoubtedly has the upper hand when it comes to online interaction: World of Warcraft players.

World of Warcraft: Social Interaction Through Avatars

A writer for Time states the reasons for the massive popularity of online role-playing games quite well: “[My generation’s] assumptions were based on the idea that video games would never grow up. But no genre has worked harder to disprove that maxim than MMORPGs—Massively Multiplayer Online Games (Coates, 2007).” World of Warcraft (WoW, for short). The most popular MMORPG of all time has more then 11 million subscriptions and counting . Players must complete “quests” to advance in the inherently social game, and playing with multiple people makes many of the quests significantly easier. Players often form small, four- to five-person groups at the beginning of the game, but by the end of the game, larger “raiding parties” can reach up to 40 players.

Additionally, WoW offers a highly developed social networking feature called “guilds.” Players create or join a guild, which they can then use to band with other guilds to complete some of the most challenging quests. “But once you’ve got a posse, the social dynamic just makes the game more addictive and time-consuming,” writes Clive Thompson for Slate (Thompson, 2005). Although these guilds do occasionally meet up in real life, they spend most of their time together online for hours per day (which amounts to quite a bit of time together), and some of the guild leaders profess to seeing real-life improvements. Joi Ito, an Internet business and investment guru, joined WoW long after he had worked with some of the most successful Internet companies; he says he “definitely (Pinckard, 2006)” learned new lessons about leadership from playing the game. Writer Jane Pinckard, for video game blog 1UP, lists some of Ito’s favorite activities as “looking after newbs [lower-level players] and pleasing the veterans,” which he calls a “delicate balancing act,” even for an ex-CEO (Pinckard, 2006).

World of Warcraft’s large subscription base, currently exceeding 12 million subscribers, broke the boundaries of previous MMORPGs. The social nature of the game has attracted unprecedented numbers of female players (although men still make up the vast majority of players ), and critics cannot easily label its players as antisocial video game addicts. On the contrary, calling them social video game players seems most appropriate, judging from the general responses given by players as to why they enjoy the game. This type of play certainly points to a new way of online interaction that may continue to grow in the coming years.