12.2 History of Advertising

Advertising promotes a product or service through the use of paid announcements (Dictionary). These announcements have had a profound impact on modern culture and thus deserve considerable attention in any treatment of the media’s influence on culture.

History of Advertising

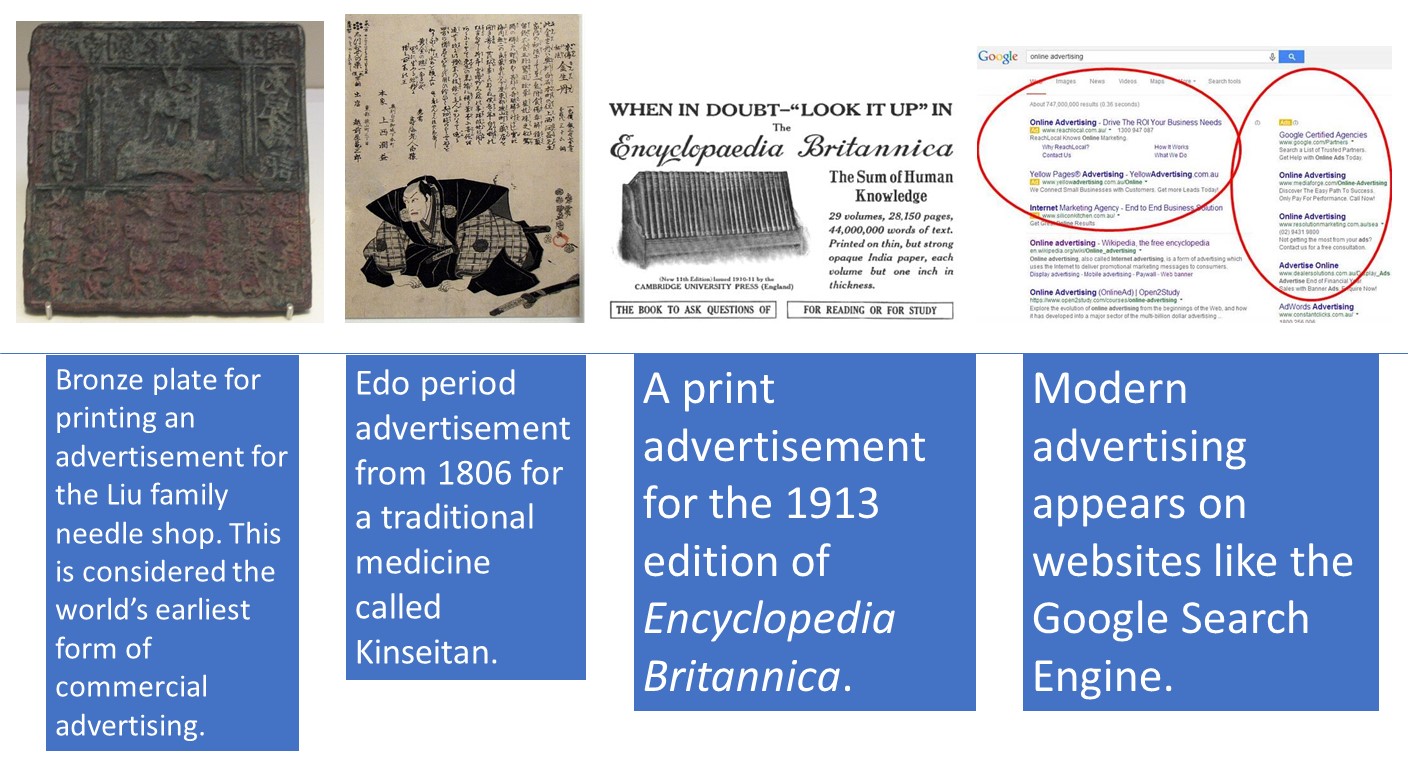

Advertising dates back to ancient Rome’s public markets and forums and continues into the modern era in most homes around the world. Contemporary consumers relate to and identify with brands and products. Advertising has inspired an independent press and conspired to encourage carcinogenic addictions. An exceedingly human invention, people cannot avoid advertising in the modern world.

Ancient and Medieval Advertising

In 79 CE, the eruption of Italy’s Mount Vesuvius both destroyed and ultimately preserved the ancient city of Pompeii. Historians have utilized the city’s archaeological evidence to reconstruct various aspects of ancient life. Pompeii’s ruins reveal a world whose products demonstrate the application of fundamental tenets of commerce and advertising. Merchants offered different brands of fish sauces identified by various names such as “Scaurus’ tunny jelly.” They also branded wines, and their manufacturers sought to position them by making claims about their prestige and quality. Toys and other merchandise found in the city bear the names of famous athletes, providing, perhaps, the first example of endorsement techniques (Hood, 2005).

The invention of the printing press in 1440 made it possible to print advertisements for posting and/or distributing to individuals. By the 1600s, newspapers had begun to include advertisements on their pages. Advertising revenue allowed newspapers to print independently of secular or clerical authority, eventually achieving daily circulation. By the end of the 16th century, most newspapers contained at least some advertisements (O’Barr, 2005).

Selling the New World

European colonization of the Americas during the 1600s brought about one of the first large-scale advertising campaigns. When European trading companies realized that the Americas held economic potential as a source of natural resources such as timber, fur, and tobacco, they attempted to convince others to cross the Atlantic Ocean and work to harvest this bounty. The advertisements for this venture described a paradise without beggars and with plenty of land for those who made the trip. The advertisements convinced many impoverished Europeans to become indentured servants to finance their voyage (Mierau, 2000).

Nineteenth-Century Roots of Modern Advertising

The rise of the penny press during the 1800s had a profound effect on advertising. The New York Sun adopted a novel advertising model in 1833, which enabled it to sell issues of the paper for a minimal amount, thereby ensuring higher circulation and a wider audience. This larger audience, in turn, justified higher prices for advertisements, allowing newspapers to make a profit from their ads for the first time (Vance).

Barnum’s Big Top of Buzz: Advertising in the Unregulated 1800s

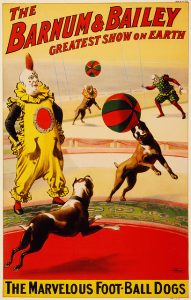

The career of P. T. Barnum, co-founder of the famed Barnum & Bailey Circus, provides insight into the unregulated nature of advertising during the 1800s. He began his career in the 1840s, writing ads for a theater, and soon after, he began promoting his shows. He advertised these shows any way he could, using not only interesting newspaper ads but also bands of musicians, paintings on the outside of his buildings, and street-spanning banners. Barnum also learned the effectiveness of using the media to gain attention by using an early form of public relations. In an early publicity stunt, Barnum hired a man to wordlessly stack bricks at various corners near his museum during the hours preceding a show. When this activity drew a crowd, the man went to the museum and bought a ticket for the show. This stunt drew such large crowds over the next two days that the police forced Barnum to halt it, thereby gaining it even wider media attention. Someone sued Barnum for fraud over a bearded woman featured in one of his shows; the plaintiffs claimed that she was, in fact, a man. Rather than trying to keep the trial quiet, Barnum drew attention to it by parading a crowd of witnesses attesting to the bearded woman’s gender, drawing more media attention—and more customers.

Barnum aimed to make his audience reflect on their experience for an extended period. His Feejee mermaid—a mummified monkey and fish sewn together—did not necessarily interest audiences because they thought the creation was a mermaid, but because they weren’t sure if it was or not. Such marketing tactics brought Barnum’s shows out of his establishments and into social conversations and newspapers (Applegate, 1998). Although most companies today would eschew Barnum’s outrageous style, many have used the media and a similar sense of mystery to promote their products. Apple, for example, famously keeps its products, such as the iPhone and iPad, under wraps, building media anticipation and coverage.

In 1843, Volney Palmer, a salesman, founded the first U.S. advertising agency in Philadelphia. The agency generated revenue by connecting potential advertisers with newspapers. By 1867, other agencies had formed, and advertisements could now reach national audiences. During this time, George Rowell, who made a living buying bulk advertising space in newspapers to subdivide and sell to advertisers, began conducting market research in its modern, recognizable form. He used surveys and circulation counts to estimate the number of readers and anticipate effective advertising techniques. His agency gained an advantage over other agencies by offering advertising space most suited for a particular product. This trend quickly caught on with other agencies. In 1888, Rowell started the first advertising trade magazine, Printers’ Ink (Gartrell).

As mentioned in Chapter 5, McClure’s owed its success in 1893 to its advertising model: it would sell issues for nearly half the price of other magazines and rely on advertising revenues to make up the difference between the cost and the sales price. Magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal focused on specific audiences, allowing advertisers to market products designed for a particular demographic. By 1900, Harper’s Weekly, once known for refusing advertising, featured ads on half of its pages (All Classic Ads).

The Rise of Brand Names

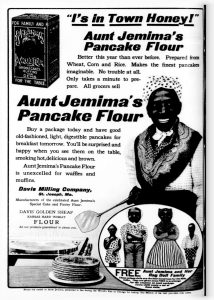

The birth of consumer culture was profoundly shaped by the advent of industrialization, a revolutionary shift from artisanal, hand-crafted goods produced in small workshops to the mass production of items in factories. Before the 1800s, brand names were essentially nonexistent, and most commerce involved direct, face-to-face interactions where products were often generic commodities. This era of transformation also coincided with modernization, moving societies away from a structure where individuals’ identities were predetermined mainly by birthright to one where people could actively choose and present their desired selves to the world.

During most of the 19th century, consumers purchased goods in bulk, weighing out scoops of flour or sugar from large store barrels and paying for them by the pound. Innovations in industrial packaging enabled companies to mass-produce bags, tins, and cartons with branded names. Although brands existed before this time, they were generally reserved for inherently recognizable goods, such as china or furniture. Advertising a particular kind of honey or flour made it possible for customers to ask for that product by name, giving it an edge over the unnamed competition.

The rise of department stores during the late 1800s also provided brands with a significant boost. Nationwide outlets, such as Sears, Roebuck & Company and Montgomery Ward, sold many of the same items to consumers across the country. A particular item spotted in a big-city storefront could come to a small-town shopper’s home thanks to mail-order catalogs. Customers made associations with the stores, trusting them to have a particular kind of item and to provide quality wares. Essentially, consumers came to trust the store’s name rather than its specific products.

Sticking to the Name: VELCRO’s Battle for Brand Identity

Branding is the strategic process of establishing a distinct identity for a company’s product, logo, or trademark in the mind of the consumer. This identity is crucial for differentiating products in a crowded marketplace and fostering customer loyalty. Given the immense value associated with successful brands, almost all brands are meticulously trademarked, and companies vigilantly protect these intellectual property rights, often resorting to legal action for copyright or trademark infringement if their branding is used without permission. A real-world example of this is the case where 5-Hour Energy successfully sued 6-Hour Energy for using similar branding, demonstrating the legal recourse available to protect a brand’s unique presence.

However, the responsibility to protect a brand lies squarely with the company, and this is where the story of VELCRO becomes particularly illuminating. If a brand name becomes so commonly used that it transforms into a generic term for an entire category of products, the company risks losing its trademark protection. This phenomenon is known as “genericide.” For instance, “aspirin” was once a brand name, but it became so widely used that it is now a generic term for a type of pain reliever, and its original trademark protection was lost. Similarly, “escalator” and “zipper” were once protected brand names before suffering the same fate.

To prevent this very outcome, VELCRO Companies go to extraordinary lengths to ensure their brand name is not used generically. They understand that their product, the hook-and-loop fastener, is incredibly popular, almost ubiquitous, and the risk of “VELCRO” becoming a generic term for all hook-and-loop fasteners is constant and significant. This proactive approach is vital for the company to maintain the distinctiveness and legal protection of its valuable brand.

VELCRO Companies actively educates the public, often through extensive campaigns and strict guidelines, that “VELCRO®” is a brand name and that the general, generic term for the product is “hook-and-loop fasteners.” They regularly issue public statements, create informative videos, and even provide detailed style guides to journalists, educators, and manufacturers, urging them to use the trademark correctly. A particularly memorable and successful example of their proactive defense was their viral YouTube video, “Don’t Say Velcro,” released in 2017. This humorous, yet firm, video featured lawyers rapping about the importance of using “VELCRO® Brand Hook and Loop Fasteners” correctly, cleverly using self-awareness to highlight their serious legal concern. The video garnered millions of views, effectively bringing awareness to their brand protection efforts in an engaging way.

The company’s stance is not merely pedantic; it’s a critical legal defense. If they fail to police their trademark, they risk a court ruling that the term has become generic, thus losing the exclusive rights to their brand name, which would significantly diminish their market position and financial value. This vigilant defense, combining traditional legal strategies with modern digital campaigns, highlights the immense ongoing effort required by successful brands to protect their intellectual property from the very popularity they strive to achieve.

Advertising Gains Stature During the 20th Century

Although advertising has become increasingly accepted as an element of mass media, many still regard it as an unseemly industry. This attitude began to change during the early 20th century. As magazines—widely considered a highbrow medium—began to incorporate more advertising, the advertising profession began to attract a greater number of artists and writers. Writers used verse, and artists produced illustrations to embellish advertisements. Not surprisingly, this era gave rise to commercial jingles and iconic brand characters such as the Jolly Green Giant and the Pillsbury Doughboy.

Advertising played a critical role in this evolving landscape, not merely informing but actively helping to shape these newfound identities. As industrial output created an economy of abundance, where goods were plentiful and often exceeded what people immediately needed, the focus shifted. Banker Paul Mazur of Lehman Brothers articulated a pivotal moment in this transition in 1927, who famously declared, “We must shift America from a needs to a desires culture. People must be trained to desire, to want new things even before the old have been entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality in America. Man’s desires must overshadow his needs.” This philosophy underpinned the rise of modern advertising, which sought to cultivate aspiration and a constant yearning for new products, even when existing ones were still perfectly functional. This move from fulfilling basic needs to cultivating an endless cycle of desires became a cornerstone of the burgeoning consumer society.

The household cleaner Sapolio produced advertisements that capitalized on the artistic advertising trend. Sapolio’s ads featured various drawings of the residents of “Spotless Town” along with a rhymed verse celebrating the virtues of this fictional haven of cleanliness. The public anticipated each new ad in much the same way people today anticipate new TV episodes. The ads became so popular that citizens passed “Spotless Town” resolutions to clean up their jurisdictions. Advertising trends later moved away from flowery writing and artistry, but the lessons of those memorable campaigns continued to influence the advertising profession for years to come (Fox, 1984).

Advertising Makes Itself Useful

World War I fueled a boom in advertising and propaganda. Corporations that had switched to manufacturing wartime goods sought to maintain their public image by advertising their patriotism. Equally, the government needed to encourage public support for the war, employing such techniques as the famous Uncle Sam recruiting poster. President Woodrow Wilson established the advertiser-run Committee on Public Information to produce movies and posters, write speeches, and generally sell the war to the public. Advertising helped popularize World War I on the home front, and the war, in turn, gave advertising a much-needed boost in stature. The postwar return to regular manufacturing marked the beginning of the 1920s as an era of unprecedented advertising.

Broadcasting Welcomes Advertising

The burgeoning film industry made celebrity testimonials, or product endorsements, a crucial aspect of advertising during the 1920s. Film stars, including Clara Bow and Joan Crawford, endorsed products such as Lux toilet soap. In the early days of mass-media consumer culture, film actors and actresses provided their audiences with figures to emulate as they began to participate in popular culture.

As discussed in Chapter 7, “Radio”, radio became an accepted commercial medium during the 1920s. Many initially thought that advertising would not work on the radio, as they believed people would find ads too intrusive in their home environment. By the end of the decade, advertising had become an integral aspect of programming. Advertising agencies often created their programs, which networks then distributed. As advertisers conducted surveys and researched prime-time slots, radio programming evolved to appeal to their target demographics. A brand of soap, for example, named and sponsored the famous Lux Radio Theater. Product placement also appeared in these early radio programs. Ads for Jell-O appeared during the Jack Benny Show (JackBennyShow.com), and Fibber McGee and Molly scripts often involved their sponsor’s floor wax (Burgan, 1996). The relationship between a sponsor and a show’s producers did not always work harmoniously; the producers of radio programs could not broadcast any content that might reflect poorly on their sponsor.

The Great Depression and Backlash

Unsurprisingly, the Great Depression, with its widespread decline in income and purchasing power, hurt the advertising industry. Spending on ads dropped to a mere 38 percent of its previous level. Social reformers added to revenue woes by again questioning the moral standing of the advertising profession. Books such as Through Many Windows and Our Master’s Voice portrayed advertisers as dishonest and cynical, willing to say anything to make a profit and unconcerned about their influence on society. Humorists also questioned advertising’s authority. The Depression-era magazine Ballyhoo regularly featured parodies of ads, similar to those seen later in the modern era on Saturday Night Live or in The Onion, that further reduced advertising’s public standing.

This advertising downturn lasted only as long as the Depression. As the United States entered World War II, advertising again returned to encourage public support and improve the image of businesses.

The growing consumer movement during the Great Depression made false and misleading advertising a significant public policy concern. At the time, companies such as Fleischmann’s (which claimed its yeast could cure crooked teeth) used advertisements to pitch misleading assertions. Only the morals of business owners stood in the way of such claims until 1938, when the federal government created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and gave it the authority to halt false advertising.

In 1955, television surpassed all other media in advertising. TV provided advertisers with unique, geographically oriented mass markets they could target with regionally appropriate ads (Samuel, 2006). The 1950s saw a 75 percent increase in advertising spending, faster than any other economic indicator at the time

Single sponsors created early TV programs. These sponsors had total control over programs such as Goodyear TV Playhouse and Kraft Television Theatre. Some sponsors went as far as to manipulate various aspects of the programs. In one instance, a program run by the DeSoto car company asked a contestant to use a false name rather than his given name, Ford. The present-day network model of TV advertising emerged during the 1950s, as the costs of TV production made sole sponsorship of a show financially prohibitive for most companies. Rather than having a single sponsor, the networks began producing their shows, paying for them through ads sold to several different sponsors.

Under the new advertising model, TV producers had significantly more creative control than they did under the sole-sponsorship model.

The quiz shows of the 1950s marked the last of the single-sponsor–produced programs. In 1958, when allegations of quiz show fraud became national news, advertisers largely withdrew from programming. The quiz show scandals also added to an increasing skepticism of ads and consumer culture (Boddy, 1990).

Advertising research during the 1950s employed scientifically driven techniques to influence consumer opinion. Although the effectiveness of this type of advertising seems questionable, the idea of consumer manipulation through scientific methods became an issue for many Americans. Vance Packard’s best-selling 1957 book The Hidden Persuaders targeted this style of advertising. The Hidden Persuaders and other similar books offered a critique of 1950s consumer culture. The U.S. public has become increasingly wary of advertising claims, and is also growing increasingly weary of ads themselves. A few adventurous ad agencies used this consumer fatigue to usher in a new era of advertising and American culture (Frank, 1998).

The Creative Revolution

Burdened by association with Nazi Germany, where the company had originated, Volkswagen took a daring risk during the 1950s. In 1959, the Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) agency initiated an ad campaign for the company that targeted skeptics of contemporary culture. Using a frank personal tone with the audience and making fun of Detroit automakers’ planned obsolescence model, the campaign stood apart from other advertisements of the time. It utilized many of the consumer icons of the 1950s, such as suburbia and game shows, in a satirical manner, pitting Volkswagen against mainstream conformity and positioning it firmly on the side of the consumer. By the end of the 1960s, the campaign had become an icon of American anticonformity. The campaign’s success led other automakers to emulate it quickly. Ads for the Dodge Fever, for example, mocked corporate values and championed rebellion.

This era of advertising became known as the creative revolution for its emphasis on creativity over straight salesmanship. The creative revolution reflected the values of the growing anticonformist movement that culminated in the countercultural revolution of the 1960s. The creativity and anticonformity of 1960s advertising quickly gave way to more product-oriented conventional ads during the 1970s. Agency conglomeration, a recession, and cultural fallout all contributed to the recycling of older ad techniques. Major TV networks dropped their long-standing ban on comparative advertising early in the decade, leading to a new trend in positioning ads that compared products. Advertising wars, such as those between Coke and Pepsi and later between Microsoft and Apple, encapsulated this trend.

Innovations in the 1980s were sparked by the emergence of a new TV channel: MTV. Producers of youth-oriented products created ads featuring music and focusing on stylistic effects, mirroring the look and feel of music videos. By the end of the decade, this style had become more mainstream in products. Campaigns for the pain reliever Nuprin featured black-and-white footage with bright yellow pills, whereas ads for Michelob used grainy atmospheric effects (New York Times, 1989).

Advertising Stumbles

During the late 1980s, studies revealed that consumers were increasingly shifting away from maintaining brand loyalty. A recession, coupled with general consumer fatigue, led to an increase in purchases of generic brands and a decrease in advertising. In 1983, marketing budgets allocated 70 percent of their expenditures to ads and the remaining 30 percent to other forms of promotion. By 1993, only 25 percent of marketing budgets were allocated to advertising (Klein, 2002).

These developments led to the rise of big-box stores, such as Walmart, which focused on low prices rather than expensive name brands. Large brands remade themselves during this period, focusing less on their products and more on the ideas behind the brand. Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign, endorsed by basketball star Michael Jordan, gave the company a new direction and a new means of promotion. Nike representatives have stated that they have become more of a “marketing-oriented company” rather than a product manufacturer.

As large brands gained popularity, they also drew the attention of reformers. Companies such as Starbucks and Nike bore the brunt of the late 1990s sweatshop and labor protests. As these brands attempted to incorporate ideas beyond the scope of their products, they also came to represent larger global commercial forces (Hornblower, 2000). This type of branding increasingly incorporates public relations techniques, which are discussed later in this chapter.

The Rise of Digital Media

In the 21st century, advertisers continued to adapt to new forms of digital media. Internet outlets, such as blogs and social media forums, as well as other online spaces, have created new possibilities for advertisers. Shifts in broadcasting toward Internet formats have also threatened older forms of advertising. Video games, smartphones, and other technologies also present new opportunities, as discussed in the next section.

The Four Components of Advertising

The advertising business is a complex ecosystem comprising four interconnected components, each playing a crucial role in bringing a message to the consumer.

Firstly, the Client is the company or individual with a product, service, or idea to sell. Clients engage in advertising for a myriad of reasons: to introduce new products to the market, increase sales of existing ones, build brand awareness and loyalty, communicate changes or updates, counter competitor claims, or improve their public image. While advertising can significantly influence consumer perception and drive demand, it’s a fundamental truth that no amount of advertising can force the public to buy something they genuinely don’t want or need. Despite this, companies invest heavily in advertising. As of recent data (though exact rankings fluctuate), the top global advertisers often include conglomerates like Procter & Gamble, Amazon, L’Oréal, Samsung, and Unilever, each spending billions annually to reach their target markets.

Secondly, the Agency consists of advertising professionals who conceptualize, create, and manage advertising campaigns for their clients. The history of advertising agencies dates back to the mid-19th century, with figures like Volney B. Palmer in Philadelphia often credited with pioneering the agency model by acting as a liaison between newspapers and advertisers. Initially, agencies primarily bought and sold ad space, but their role quickly evolved to include creative services, market research, and strategic planning. Today, the advertising agency industry is a multi-billion-dollar global enterprise, characterized by a mix of large multinational networks (like WPP, Omnicom, Publicis Groupe, and Interpublic Group) and smaller, specialized boutique agencies. These agencies typically follow a systematic process to develop and release an advertisement: this includes initial client meetings to understand objectives, market research to identify target audiences and competitive landscapes, strategic planning to define the campaign’s direction, creative development (concept, copywriting, art direction), media planning and buying, production (filming, recording, printing), campaign launch, and finally, performance monitoring and analysis.

Thirdly, Media refers to the various platforms through which advertisements are delivered to the audience. The landscape of media is constantly evolving, offering a diverse array of options. Traditional platforms include television, radio, newspapers, and magazines. Television, for example, provides a vast reach and high impact through sight and sound, but can be expensive. Radio provides cost-effectiveness and targeted local reach, though it lacks visuals. Newspapers offer detailed information and a sense of credibility, but readership has declined. Magazines allow for highly targeted audiences based on interests, but have longer lead times. Digital platforms have revolutionized media, encompassing social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, TikTok), search engines (e.g., Google Ads), websites (display ads), streaming services, and mobile apps. These digital channels offer unprecedented targeting capabilities, real-time analytics, and often lower costs, but can face challenges like ad-blocking and ad fraud. “LPM” usually refers to Leads Per Mille (Latin for “per thousand”), a metric used in digital advertising to measure the number of leads generated per one thousand ad impressions, indicating the efficiency of an ad campaign in converting views into potential customers.

Finally, the Audience comprises the message recipients – the consumers or individuals the advertisement aims to influence. Advertisers employ sophisticated techniques to understand and target these audiences. Demographics segment audiences based on measurable characteristics such as age, gender, income, education level, ethnicity, and geographic location. For instance, a luxury car brand might target individuals with high incomes and a specific age range. Psychographics, on the other hand, delve into the psychological attributes of an audience, including their lifestyles, values, interests, opinions, attitudes, and behaviors. An organic food brand, for example, might target consumers who prioritize health and sustainability, regardless of their income bracket. The most coveted audience for advertisers often consists of heavy users of a product category, individuals with high disposable income, or those who are early adopters and influencers within their social circles, as these groups tend to drive significant sales and word-of-mouth promotion. Understanding these audience characteristics is paramount for crafting messages that resonate and ultimately achieve the client’s advertising objectives.