13.3 The Internet’s Effects on Media Economies

The challenge to media economics deals with production. When print media had no competition, the concept was simple: Sell newspapers, magazines, and books. Companies could gauge the sales of these goods like any other product, although, in the media’s case, the good was intangible—information—rather than the physical paper and ink. The transition from physical media to broadcast media presented a new challenge because consumers did not pay money for radio and, later, television programming; instead, the “price” consisted of occasional interruptions by “word from our sponsors.” However, even this practice hearkened back to the world of print media; just as newspapers and magazines sell advertising space, radio and television networks sell time on their airwaves.

The minuscule cost of online space compared to that in traditional print or broadcast media, combined with the instantaneous proliferation of information, indeed initiated a fundamental shift in media economics. This digital transformation continues to pose both a grave threat and significant opportunities for traditional media.

The initial culture of providing free content on the internet, primarily supported by ads, proved unsustainable for many news organizations. Consequently, most major newspapers and high-quality news outlets have successfully implemented robust digital subscription models. For instance, The New York Times has been a leading example, demonstrating impressive subscription-driven growth, with millions of digital-only subscribers. They have achieved this by offering premium, distinctive content, implementing strategic pricing, including bundled subscriptions with products like Games and Cooking, and focusing on deep subscriber engagement to reduce churn. Similarly, The Wall Street Journal has maintained its strong paid subscription model, proving that audiences are willing to pay for high-value, specialized content. While some free articles or limited access may still exist as a sampling mechanism, the prevailing trend for quality journalism is towards paid digital access.

Traditional media outlets have responded to the digital imperative not merely by establishing an Internet presence, but by undergoing a comprehensive digital transformation and embracing a multi-platform strategy. Their archives have indeed opened up, but this content is now often behind paywalls or integrated into subscription offerings. Newspapers no longer offer video content online; they have developed sophisticated multimedia newsrooms, producing original video series, podcasts, and interactive features that leverage their journalistic expertise. Conversely, radio and television networks have expanded beyond audio and visual content to publish traditional text-and-photo stories, long-form articles, and in-depth analyses on their websites and apps.

Through various digital platforms and internal restructuring, media companies have profoundly synergized their content. They no longer merely act as television networks or local newspapers but have evolved into comprehensive digital content hubs, offering a wide range of content. This strategy aims to capture audience attention across multiple touchpoints and monetize it through diverse revenue streams. These streams now include digital subscriptions and memberships, which have become a primary focus, with tiered access, bundled products, and personalized content driving recurring revenue. Digital advertising, while traditional print ad revenue has declined, has surged, encompassing programmatic ads, video ads, and native advertising. Social media advertising, in particular, has seen renewed confidence and significant growth in 2024, with brands leveraging user-generated content and creator partnerships. Many media companies, like The New York Times with Wirecutter, integrate e-commerce and affiliate marketing, embedding product recommendations and affiliate links into their content to earn commissions on sales. Events, both virtual and in-person, often tied to specific content verticals or journalistic themes, have become a significant “other” revenue stream. Furthermore, content is licensed to other platforms, including streaming services, and syndicated across various digital channels. Some media companies even monetize their proprietary data and insights, offering research reports or specialized data services to businesses.

The economic reality of the internet has permanently changed the media landscape. The abundance of free content has intensified the “attention economy,” where media companies fiercely compete for a finite resource: user focus. This has driven a shift towards more engaging and personalized content formats, often powered by AI, and a relentless pursuit of diversified revenue models. While the challenge of dwindling traditional revenues persists, the most successful media companies are those that have innovated their content creation, distribution, and monetization strategies to thrive in this complex digital ecosystem.

The Cloud’s Silver Lining: How Adobe Subscribed to Success

Adobe’s pivotal decision to transition its business model from selling individual software licenses to offering the comprehensive Adobe Creative Cloud subscription service marked a significant turning point, fundamentally reshaping the creative software industry and solidifying Adobe’s position as an undeniable industry standard. Previously, users would purchase a perpetual license for software like Photoshop, Illustrator, or Premiere Pro, incurring a substantial upfront cost and then facing additional expenses for major version upgrades every few years. This model often meant users were working on outdated software to avoid upgrade costs, and it also created a lucrative environment for software piracy.

The shift to Creative Cloud introduced a subscription-based model where users pay a recurring monthly or annual fee to access a suite of applications. This change, initially met with resistance from a segment of their user base who preferred owning their software outright, proved highly advantageous for several reasons, ultimately establishing Adobe as an industry standard.

Firstly, the subscription model provided continuous access to the latest versions and updates. Instead of waiting for a new major release, Creative Cloud users automatically receive feature enhancements, bug fixes, and performance improvements as soon as they are available. This meant professionals always had the most cutting-edge tools at their disposal, crucial in fast-evolving fields like graphic design, video editing, and web development.

Secondly, Creative Cloud enabled seamless integration and a unified workflow across multiple applications. With a single subscription, users could access a vast array of Adobe products, from Photoshop and Illustrator to InDesign, Premiere Pro, and After Effects. This facilitated smoother project handoffs, consistent asset management through Creative Cloud Libraries, and a more cohesive creative ecosystem. For instance, a designer could easily create vector graphics in Illustrator, import them into Photoshop for photo manipulation, and then use them in an animation created in After Effects, all within a seamlessly integrated environment. This comprehensive toolkit became indispensable for creative professionals who often utilize multiple applications for complex projects.

Thirdly, the subscription model made Adobe’s powerful software more accessible and affordable upfront. While the long-term cost could potentially exceed perpetual licenses for very infrequent users, the lower monthly entry point allowed students, freelancers, and small businesses to gain access to professional-grade tools without a hefty initial investment. This broad accessibility fostered a larger user base and created a self-reinforcing cycle where more users meant more industry training, more online tutorials, and more jobs requiring Adobe proficiency, further cementing its standard status.

Finally, the cloud-based nature of the service offered enhanced collaboration and cloud storage capabilities. Teams could easily share files, track versions, and collaborate on projects in real-time, regardless of their physical location. This flexibility became particularly valuable for remote workforces and distributed teams, streamlining creative workflows and increasing productivity. By transforming from a product vendor to a service provider, Adobe successfully adapted to the digital age, combating piracy, ensuring a predictable revenue stream, and fostering an unparalleled ecosystem that is now virtually synonymous with professional creative work.

Online Synergy

The internet has also drastically changed the way companies’ advertising models operate. During the early years of the internet, many web advertisements primarily directed traffic toward e-commerce sites like Amazon and eBay for direct product or service purchases. Today, however, digital advertising is far more sophisticated and pervasive. Ads, particularly on sites for high-profile media outlets, now commonly highlight products and services that consumers might not typically purchase online, such as automobiles, financial services, or major credit cards.

A significant evolution in advertising has been the prominence of highly targeted, data-driven approaches. This involves matching advertisers with specific user demographics, interests, and online behaviors, often in real-time through programmatic advertising. For instance, if a web page provides suggestions on how to fix a refrigerator, some of the targeted advertisements would likely include local refrigerator repair shops or appliance parts suppliers. This precision extends beyond simple keyword matching to encompass a deep understanding of user intent and context.

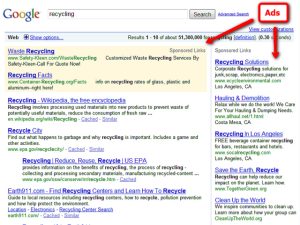

Search engine giant Google has been a pioneer in perfecting this type of targeted advertising. Through its robust advertising platforms, Google Ads (formerly Google AdWords) and Google AdSense, it has fundamentally reshaped the advertising landscape. Google Ads allows businesses to bid on keywords and display highly relevant text ads next to search results, on various websites (through the Google Display Network), and within its free web-based services like Gmail and YouTube. Conversely, Google AdSense enables website publishers to automatically display targeted ads on their sites and earn revenue based on clicks or impressions.

Google’s innovation lies not just in using advanced algorithms to sort through massive amounts of data and match advertising to content, but also in significantly lowering the cost barrier and volume barrier to advertising. Because Google automatically connects publishers with advertisers, an independent website can easily integrate Google AdSense to monetize its content, earning revenue for each user interaction with the displayed ads. Likewise, relatively small companies can purchase advertising space in specialized niches through Google Ads without the need for large-volume ad buyers. This business model has proven immensely productive; the vast majority of Alphabet’s (Google’s parent company) revenue, totaling hundreds of billions annually, comes from its advertising segments, even as it provides many services like email and document sharing at no direct cost to the user. This ongoing evolution underscores how digital platforms have not only transformed content consumption but also fundamentally redefined the economics of media through data-driven, highly targeted advertising.

Problems of Digital Delivery

Search engines like Google and video-sharing sites like YouTube, owned by Google’s parent company Alphabet, primarily function as aggregators and hosts of information created by others, rather than direct content producers themselves. While YouTube once pursued original programming, its current focus is on funding and supporting its vast network of independent creators. This fundamental dynamic, where platforms provide free access to content, continues to create significant tension with those who financially depend on its creation and sale. News publishers, for instance, have largely abandoned the early internet’s “free content” model, with major outlets like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal successfully implementing paid digital subscriptions, a stark contrast to previous decades. This ongoing challenge is further complicated by the rise of AI in search, which can summarize information directly, potentially reducing traffic to sources. Despite these tensions, platforms like Google heavily rely on advertising, utilizing programs such as Google Ads and Google AdSense to connect advertisers with relevant content and audiences, thereby lowering entry barriers for both advertisers and publishers and forming the bulk of Alphabet’s revenue.

Google News

Google News, a prominent news aggregator owned by Alphabet, continues to automatically collect and organize news stories from various internet sources, providing users with a convenient portal to access the latest headlines from multiple outlets. However, the relationship between Google and news publishers remains a complex and often contentious one, evolving significantly since the early criticisms.

The historical contention that Google infringed on copyrights and cost publishers revenue, famously articulated by The Wall Street Journal‘s editor Robert Thomson in April 2009, who described news aggregators as “parasites,” still resonates with many in the media industry (Schulze, 2009). While Google did respond in December 2009 by allowing publishers to set limits on free article views, this was an early step in a much more protracted and intricate negotiation.

In the modern digital landscape of 2024-2025, the core issue persists: how to fairly compensate content creators for the value derived from their journalism when platforms like Google facilitate access, often without direct payment for the content itself. This has led to several key developments. In a significant shift, Google launched News Showcase. In this program, participating publishers are directly paid to curate and display their premium content within Google News, Google Discover, and other platforms. This initiative aims to provide direct financial support and increased visibility for news organizations, moving beyond a purely traffic-referral model. The advent of AI-generated summaries in Google Search results, known as AI Overviews, has introduced a new layer of concern for publishers. While these summaries aim to provide quick answers to user queries, many news outlets report significant drops in referral traffic, as users may no longer need to click through to the source. Publishers argue that this “zero-click” phenomenon directly impacts their advertising revenue and subscriber acquisition efforts, leading to renewed calls for transparency and fair compensation. Globally, news publishers and governments have increased pressure on tech giants to pay for news content. Influenced by initiatives like Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code, Google has entered into various licensing agreements with publishers worldwide, though the terms often remain confidential. Furthermore, Google is actively exploring new AI licensing deals with news publishers to compensate them for their content used to train and power its artificial intelligence tools, acknowledging the value of high-quality, authoritative information in the AI era. Google News has also transitioned to automatically generated publication pages, moving away from manual submissions and customization options previously available to publishers. This streamlines the process but also means Google’s algorithms increasingly determine how content is presented, further influencing visibility and user engagement.

In essence, while the “parasite” accusation from 2009 highlighted an early imbalance, the relationship has evolved into a complex ecosystem of negotiation, direct payments, and ongoing adaptation. Publishers are actively seeking diversified revenue streams, including subscriptions and direct deals, while continuing to grapple with the impact of evolving search and AI technologies on their traffic and financial sustainability.

Music and File Sharing

The clash between digital platforms and traditional news media is merely one facet of the profound challenges and transformations ushered in by digital technology. The inherent ability of digital formats to create exact, lossless copies of data dramatically amplified the risk of piracy across various media industries. In the music industry, this threat became acutely apparent with the widespread adoption of peer-to-peer file-sharing services in the late 1990s. Platforms like Napster, which enabled users to freely share MP3 files directly with one another, quickly gained immense popularity, leading to unprecedented levels of copyright infringement and a significant decline in traditional music sales.

However, the music industry’s response to this initial wave of digital piracy has evolved considerably beyond simply legal battles. While aggressive legal action against file-sharing platforms and individual users did lead to the shutdown of services like Napster and LimeWire in the early 2000s, the industry recognized that a purely punitive approach was unsustainable in the face of changing consumer behavior. This realization spurred a pivotal shift towards embracing legitimate digital distribution models.

The landscape of how music generates revenue on online platforms has undergone a significant transformation, moving from physical sales to primarily digital models. Broadly, two standard business models dominate this space: downloads and subscription services.

Downloads, while less cutting-edge now, represented a crucial early victory for the music industry in the digital realm. The introduction of iTunes in 2003 marked a turning point, successfully persuading consumers to pay for digital music after years of widespread piracy. Before this, the music industry grappled with unauthorized file-sharing services like Napster. iTunes provided a legal, convenient, and relatively affordable way to acquire individual tracks or whole albums, establishing a viable revenue stream for artists and labels in the nascent digital music market. Although it still exists, the download model has significantly declined in prominence as streaming has become the preferred method of consumption for most listeners.

Subscription services, on the other hand, have grown remarkably in recent years and represent the dominant revenue stream for music today. These services offer immense potential for new and diverse income streams for artists and the music industry. Many operate on a freemium model, where some content or basic functionality is offered for free, but a monthly subscription is required to unlock all the site has to offer. For instance, platforms like LiveOne (formerly LiveXLive), Pandora, Spotify, and Apple Music all utilize variations of this model. Spotify, the most well-known example, offers a free tier supported by advertisements and with limited features (like restricted skips or shuffle-only play). At the same time, its premium subscription provides an ad-free experience, offline downloads, and unlimited skips. This strategy enables platforms to attract a massive user base through free offerings, then convert a percentage of those users into paying subscribers, generating significantly more revenue.

Beyond these established platforms, crowdfunding has emerged as a powerful alternative for artists to directly engage with their fanbase and secure funding for their projects. Platforms like Kickstarter allow musicians to solicit financial contributions from fans in exchange for various rewards, ranging from digital downloads and exclusive merchandise to personalized experiences. A famous, albeit controversial, example is Amanda Palmer of the Dresden Dolls. In 2012, she launched a Kickstarter campaign for her album “Theatre Is Evil,” initially aiming to raise $100,000. The campaign vastly exceeded expectations, earning an astonishing $1.2 million. However, Palmer later faced significant public chastisement for publicly asking musicians to perform with her on tour for “beer, hugs, and high fives” in the wake of her substantial crowdfunding success. This sparked a contentious debate about fair compensation for artists and the ethics of crowdfunding.

Current trends in crowd-sourcing for music extend beyond one-off project funding. Many artists now utilize subscription-based crowdfunding platforms like Patreon, where fans become “patrons” and provide ongoing financial support in exchange for exclusive content, early access to new music, behind-the-scenes glimpses, or direct interaction with the artist. This model fosters a deeper, more consistent relationship between artists and their most dedicated fans, providing a predictable income stream that is less reliant on the fluctuating payouts from streaming services. Additionally, artists are increasingly exploring direct-to-fan sales via their websites or platforms like Bandcamp, which often offer a higher percentage of revenue directly to the artist compared to primary streaming services, giving them more control over their music and its monetization. The rise of Web3 technologies, including NFTs, is also beginning to create new avenues for fan engagement and artist compensation, offering unique digital collectibles and fractional ownership of music rights, though these are still nascent developments.

Despite ongoing challenges, the music industry has largely recovered and is experiencing sustained growth, primarily driven by streaming revenue. Paid subscriptions now account for the majority of global recorded music revenue, with physical sales, particularly vinyl, experiencing a niche resurgence. The industry continues to invest in anti-piracy technologies, including AI-powered content recognition and digital watermarking, and fosters collaborations between streaming platforms and anti-piracy organizations. This evolution from a direct battle against file-sharing to a comprehensive strategy embracing accessible legal alternatives demonstrates the music industry’s dynamic adaptation to the digital age.

Video Streaming

As high-bandwidth internet connections proliferated, video-sharing and streaming sites like YouTube emerged, fundamentally transforming how video content is created, distributed, and consumed. While YouTube initially gained prominence as a platform for users to upload and share amateur videos, its scope rapidly expanded to include professional content, music videos, and clips from television shows. However, the ease of digital replication and online transmission also led to significant challenges, as some users exploited these platforms to post a high volume of copyrighted commercial content illegally.

This inherent replication potential, combined with widespread online access, has driven a profound shift across media industries, particularly affecting those that traditionally relied on direct consumer income from film and television. The early era of rampant piracy, where unauthorized television show episodes and movies were widely shared, pushed the industry to innovate its business models. This led to the rise of dedicated video streaming services such as Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, Max, and Amazon Prime Video. These platforms initially offered vast libraries of licensed content, then increasingly invested in producing their exclusive original programming to attract and retain subscribers, leading to the “streaming wars” of the 2010s and early 2020s.

In 2024, the video streaming landscape is characterized by a mix of subscription-based models and the growing prominence of ad-supported tiers, as services seek to diversify revenue and appeal to a broader audience. Many major streaming providers now offer cheaper, ad-supported plans alongside their premium, ad-free subscriptions. Live sports content has also become a significant driver for subscriber acquisition and advertising revenue on platforms like Peacock and Max. This evolution has dramatically impacted traditional television and film industries, accelerating the trend of “cord-cutting” as viewers abandon linear cable and satellite subscriptions in favor of on-demand streaming. Movie studios are increasingly releasing films directly to streaming platforms, challenging the traditional theatrical window.

Despite the widespread availability of legal streaming options, video piracy remains a persistent challenge, evolving into new forms like illegal streaming sites, torrenting, and credential sharing for subscription services. The industry continues to combat this through technological measures, including digital rights management (DRM) and AI-powered content recognition, alongside legal enforcement and international collaborations. This dynamic interplay between technological advancement, shifting consumer behavior, and ongoing efforts to monetize content underscores the significant transformation of the video media landscape. However, as the next section will demonstrate, this pervasive shift of media and information to the internet can also pose a risk of a digital divide, where individuals without internet access face an even greater disadvantage in navigating everyday life.

Safe Harbors and Shifting Sands: The DMCA’s Evolving Role in Online Media

Content producers continue to rely on legal frameworks to protect their intellectual property in the digital realm. In 1998, the United States Congress enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) with the primary goal of adapting copyright law for the internet age and curbing the unauthorized copying and distribution of copyrighted material. This landmark legislation clarified many digital “gray areas” that previously lacked explicit legal coverage. Key provisions included making it illegal to circumvent technological measures designed to protect copyrighted works (often referred to as Digital Rights Management or DRM), establishing requirements for webcasters to pay licensing fees to record companies, and granting specific exemptions for libraries, archives, and certain other nonprofit institutions under defined circumstances (U.S. Copyright Office, 1998).

Since its enactment, the DMCA has formed the foundational legal basis for numerous claims against major online platforms, including user-generated content sites like YouTube. Under the law’s “notice and takedown” provisions (specifically Title II, the Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act or OCILLA), copyright holders can send formal notifications to internet hosts or online service providers (OSPs) distributing their copyrighted material without permission. By certifying a good-faith belief that the host lacks prior authorization, copyright holders can request the swift removal or disabling of access to that content from the site. This process has become a ubiquitous mechanism for copyright enforcement online, with many large platforms, including YouTube, developing sophisticated automated systems like Content ID to manage and respond to these notices at scale.

Crucially, the DMCA also established “safe harbor” protections for internet service providers (ISPs) and other online service providers. This provision clarifies that ISPs are generally not liable for copyright infringement committed by their users, provided they adhere to specific requirements. These include adopting and implementing a policy for terminating repeat infringers, accommodating standard technical measures used by copyright owners to identify and protect their works, and, most notably, expeditiously removing or restricting access to allegedly infringing material upon receiving a valid takedown notice. This safe harbor was designed to foster the growth of internet services by alleviating the burden on ISPs to police their vast networks for illegal content proactively.

While the DMCA has provided essential clarity and protection for copyright holders and has enabled the growth of online platforms, it has not been without its critics. Corporations can find the process of issuing individual takedown notices time-consuming, especially given the sheer volume of content uploaded daily. Conversely, concerns have been raised that the system’s relative lack of strong safeguards can allow large companies or even malicious actors to abuse the notice-and-takedown process, potentially bullying smaller sites or individuals into removing legitimate or fair-use content, given only a good-faith notice. The U.S. Copyright Office itself has acknowledged that the operation of the Section 512 safe harbor system can be unbalanced, identifying areas for potential refinement.

Looking ahead to 2024 and beyond, the DMCA continues to be a central, yet increasingly scrutinized, piece of legislation. The rapid evolution of digital media, including the proliferation of streaming services, user-generated content, and particularly the emergence of generative artificial intelligence, poses new complexities for copyright law. The use of copyrighted material to train AI models and the copyrightability of AI-generated outputs are actively debated issues that are prompting new legal challenges and discussions about whether the DMCA, enacted over two decades ago, will require further amendments to adequately address these cutting-edge technologies and ensure a balanced approach to intellectual property in the ever-expanding digital landscape.

The New Reality of Syndication

The economics of producing a hit TV show have been dramatically altered by the rise of streaming, making a successful series potentially worth hundreds of millions of dollars less than it would have been in the “old system,” as highlighted by Forbes contributor Matt Craig. This fundamental shift stems from the different business models that underpin broadcast television versus streaming platforms.

In the traditional television landscape, studios and television networks operated as distinct entities. Studios bore the financial burden of producing shows, often incurring significant deficits, and then licensed or “rented out” their content to networks for initial broadcasts. While most shows didn’t recoup their costs in the initial network run, the actual profitability came from syndication. Once a show reached around 100 episodes, it became eligible for syndication, meaning it could be re-licensed to cable TV channels, other broadcast stations for reruns, and eventually to overseas markets and, later, to early streaming services. This long tail of reruns and re-licensing could generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for the studios, which then trickled down to talent through residuals and profit participation.

However, the advent of streaming fundamentally disrupted this model. Streaming services offered a significantly cheaper alternative to cable for consumers, providing vast libraries of content on demand. Initially, studios licensed their existing content to these streamers, creating new revenue streams. The critical turning point occurred when streaming services began to produce their own high-quality, original content, directly competing with traditional networks and studios. As viewers flocked to streaming platforms for this exclusive and on-demand programming, traditional cable television began to decay.

The core issue is that because “everyone went to streaming,” the overall pool of money available for content has paradoxically become less in certain key areas. The streaming business model, exemplified by giants like Netflix, is fundamentally different and, in many ways, worse for a show’s long-term profitability and talent compensation. In this new paradigm, the same company that pays for a show also broadcasts it and serves as its exclusive repository.

This integrated model removes the traditional incentives for hit shows. Since Netflix (or other streamers) primarily earns revenue through subscriptions, a single “hit” show doesn’t necessarily translate into a massive, direct increase in advertising revenue that could be shared with the studio or talent. There’s less incentive for streamers to endlessly renew a show if its primary purpose of attracting initial subscribers has been served, as they don’t benefit from a continuous, incremental revenue increase from reruns or syndication in the same way traditional networks did.

Consequently, talent, including actors and showrunners, now have significantly less leverage for negotiating raises or receiving substantial backend profits. Consider The Bear, a critically acclaimed and highly popular show that has swept the Emmys. While it’s a critical darling, its actors and showrunners are not being paid like the stars of past network hits. An Emmy-winning star might earn, for example, $750,000 a year, but with little to no hope for significant residuals. This pales in comparison to the massive, long-term residual checks that stars of syndicated hits like Friends continued to receive for decades. In the streaming era, awards do not necessarily equal substantial long-term financial gain for talent.

Moreover, streaming shows typically have fewer episodes per season, making it far more challenging to reach the 100-episode threshold traditionally required for profitable syndication. The Bear, for instance, with three seasons totaling just 28 episodes, will likely never see syndication in the traditional sense, meaning its revenue-generating potential ends where it starts, for the most part. This lack of a “backend” has contributed to a significant contraction in the TV industry, as evidenced by the widespread strikes of the past year (referring to the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes of 2023).

Iconic TV producers like Dick Wolf, known for creating sprawling, long-running franchises such as Law & Order and Chicago, amassed immense wealth (reportedly over $600 million) primarily through the syndication model, with his shows constantly airing across various networks and earning continuous licensing fees. It is doubtful that anyone will be able to follow in his financial footsteps under the current streaming paradigm. Instead, as the industry tightens its belts, TV producers may find themselves living more like well-compensated doctors rather than “princes” of media empires.

While TV content is arguably more popular and diverse than ever, it is also significantly more fragmented across numerous streaming platforms. Broadcast TV, in contrast, increasingly caters to an older demographic, with Nielsen reporting the average age of a primetime broadcast viewer to be around 69 years old. Consequently, advertisers, especially those targeting younger, more affluent audiences, have shifted mainly their budgets away from broadcast, or are now featuring different brands, leading to a significant reduction in ad revenue for traditional networks.

Streaming, however, largely transcends age demographics and is undeniably the future of television consumption. Digital advertising on streaming platforms operates on different metrics, as it can track user behavior with much greater precision, enabling highly targeted ads and being paid on metrics like impressions or conversions rather than broad viewership numbers. This precision is what advertisers value. As broadcast TV continues its decay and potentially dies out, streaming will fully inherit its mantle. However, this doesn’t mean an ad-free future; we are already seeing an increase in commercials on streaming platforms as they seek new revenue streams beyond just subscriptions. Furthermore, in an interesting full-circle moment, major streaming players like Max and Disney+ have started offering bundled packages, echoing the bundling strategies previously employed by cable TV providers, to increase perceived value and reduce churn.

Ultimately, the question of whether talent pay will return to its previous heights is complex. While top “hitmakers” and in-demand stars will continue to command high fees upfront due to competition, the long-term, passive income from residuals and syndication that characterized the “golden age” of television appears unlikely to return to where it was, at least in the short term, due to the fundamental restructuring of the industry’s financial ecosystem.