13.7 Cultural Imperialism

Understanding the roots of cultural imperialism is crucial. It predates the United States’ emergence as a global power. In its broadest sense, imperialism denotes a nation’s assertion of control or dominant influence over another, whether through direct political and economic means or more subtle cultural penetration. Just as imperial Britain economically dominated its American colonies, it also wielded significant influence over their culture. While the cultural landscape of the colonies was a blend of nationalities—with many Dutch and Germans also settling—the ruling majority of ex-Britons generally led British culture, including its language, legal systems, and social norms, to prevail.

Today, cultural imperialism is often used to describe the United States’ pervasive role as a cultural superpower throughout the world. However, this narrative is increasingly nuanced by the rise of other cultural powerhouses. American movie studios, for instance, have historically achieved far greater global success than many of their foreign counterparts, not only due to their sophisticated business models and vast financial resources but also because the concept of Hollywood itself has become a defining trait of the modern worldwide movie business. Beyond traditional nation-states, multinational, nongovernmental corporations now play a pivotal role in driving global culture through their vast reach and integrated media empires.

This phenomenon is neither entirely good nor entirely bad. On the one hand, foreign cultural institutions and local media producers can adopt successful American business and production models, leading to higher-quality local content and more efficient distribution. Furthermore, global corporations are increasingly willing to localize content and invest in diverse storytelling that resonates with specific markets, understanding that cultural relevance often translates to greater profit. This has led to the emergence of globally successful films and series that blend local narratives with international production values, usually seen in the rise of non-Western media such as K-dramas, anime, and Bollywood films, which now boast massive global fan bases and significant cultural influence. For example, Netflix, while an American company, invests heavily in local productions worldwide, such as the South Korean series Squid Game, which became a global phenomenon, demonstrating a more reciprocal, albeit still commercially driven, cultural exchange.

However, cultural imperialism also carries potential adverse effects. Concerns persist regarding the homogenization of culture, where local traditions, languages, and artistic expressions may be diminished or displaced by dominant global forms. This can manifest in the spread of Western ideals of beauty, consumerist lifestyles, or specific social norms, potentially leading to a decline in the distinctiveness of indigenous cultures around the world. The pervasive nature of global media can have a quick and profound impact, shaping aspirations and values in ways that challenge local identities. The ongoing debate revolves around finding a balance where global cultural flows enrich rather than erode local diversity, fostering a truly multicultural global landscape.

Cultural Hegemony

Understanding the roots of cultural imperialism is crucial, and its theoretical foundations extend back to the ideas of thinkers like Antonio Gramsci. Strongly influenced by the theories and writings of Karl Marx, the Italian philosopher and critic Antonio Gramsci originated the concept of cultural hegemony to describe the subtle yet powerful dominance of one group over another, not primarily through force, but through the widespread acceptance of its worldview. Unlike Marx, who mainly focused on economic class struggle and believed that the workers of the world would eventually unite and overthrow capitalism through revolution, Gramsci argued that culture and the media exert such a profound influence on society that they can persuade subordinate groups, including workers, to consent to and even embrace a system that ultimately does not provide them with economic or social advantages. This consent is achieved when the dominant group’s values, norms, and beliefs become internalized as “common sense” or the natural order of things, even by those who they disadvantaged.

The argument that media can influence culture and politics is vividly evident in the persistent narrative of the “American Dream.” This rags-to-riches tale suggests that through hard work and talent, anyone can achieve a successful life regardless of their starting point. While individuals may indeed find truth in this adage, contemporary research indicates that such stories often represent the exception rather than the rule, and that systemic inequalities related to class, race, and gender significantly impact social mobility. Moreover, recent studies show that while many young people still aspire to aspects of the American Dream (like financial security and happiness), they are increasingly skeptical of its achievability, often citing economic barriers and expressing a desire for more realistic portrayals of financial struggles in media. Social media, in particular, is now seen as a more influential source for shaping perceptions of the American Dream than traditional media like TV or movies.

Marx’s ideas about power dynamics remained at the heart of Gramsci’s beliefs, but Gramsci expanded the scope of power beyond the purely economic. According to Gramsci’s notion, the hegemons of capitalism—those who control the capital and the means of production—can assert economic power. In contrast, the hegemons of culture can assert cultural power. This concept of culture, rooted in the Marxist idea of class struggle, posits that one group dominates another, leading to a form of ideological conflict. Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony is highly relevant in the modern day, not just because of the historical dynamic of a local property-owning class oppressing people with low incomes, but even more so due to the concern that rising globalization, particularly through dominant media flows and digital platforms, will permit one culture (or a set of dominant cultural values) to so completely assert its power that it drives out or significantly marginalizes all competitors. This is often seen in debates surrounding cultural homogenization versus heterogenization, where the pervasive reach of global media conglomerates can subtly shape global consumer preferences, social norms, and even political discourse, making the dominant cultural worldview appear universal and natural.

Spreading American Tastes Through McDonaldization

The possibility that dominant global tastes and standardized systems will crowd out local cultures around the globe represents a key concern of cultural imperialism. The concept of “McDonaldization,” coined by sociologist George Ritzer in his influential 1993 book The McDonaldization of Society, applies not just to its namesake, McDonald’s, with its franchises in seemingly every country, but to any industry that adopts the principles of the fast-food industry on a large scale. Rooted in Max Weber’s theory of rationalization, McDonaldization describes a process where the principles of the fast-food restaurant are coming to dominate more and more sectors of society worldwide.

Companies employing McDonaldization take four core aspects of business to the extreme: efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control. These represent key drivers of rationalized systems in modern free markets. Efficiency involves optimizing processes to complete tasks rapidly with minimal effort, seen in innovations like drive-thru windows and self-checkout systems. Calculability emphasizes quantitative aspects over qualitative ones, focusing on speed and volume, often highlighted by slogans like “billions served” or the emphasis on large portion sizes. Predictability ensures that products and services remain consistent across different locations and times, offering a uniform experience to consumers regardless of where they are. Finally, control is exerted over both employees, through standardized procedures and automation, and customers, through limited options and environments designed to encourage quick consumption. Applying these concepts, optimized initially for financial markets, to cultural and human items such as food, education, or even healthcare, McDonaldization enforces general standards and consistency throughout a global industry.

Unsurprisingly, McDonald’s continues to serve as the prime example of this concept. With over 40,000 restaurants in more than 100 countries as of 2024, it remains one of the largest and most globally recognized fast-food chains. While the company has increasingly adapted its menu and practices to local tastes—for example, Indian restaurants offer pork-free and beef-free options like the McAloo Tikki, and many global locations feature unique regional items—the same fundamental principles of efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control still apply in a culturally specific way. The consistent branding, from the iconic Golden Arches to global marketing campaigns, contributes to its widespread recognition. According to Eric Schlosser in Fast Food Nation, the consistent branding of the company, from the “I’m lovin’ it” slogan to the Golden Arches, makes McDonald’s “more widely recognized than the Christian cross (Schlosser, 2001).” More importantly, the underlying business model of McDonald’s stays remarkably consistent from country to country. In other words, wherever a consumer travels within a reasonable range, the menu options and the resulting product, while locally flavored, adhere to a predictable standard of service and quality.

Beyond fast food, McDonaldization is evident in numerous other sectors in the 21st century. In education, “McUniversities” offer standardized curricula, online courses, and large lecture halls, prioritizing efficiency and calculability (e.g., GPA) over personalized learning. The retail sector, with its large big-box stores and e-commerce giants like Amazon, emphasizes efficiency in delivery, calculability in pricing, predictability in product availability, and control over the customer journey. Healthcare, too, can show signs of McDonaldization through standardized procedures, an emphasis on quantifiable outcomes, and streamlined patient flows, sometimes at the expense of individualized care. In entertainment, the proliferation of formulaic movie sequels, reality TV shows, and algorithm-driven content on streaming platforms can be seen as prioritizing predictability and mass consumption. Even in travel, budget airlines and global hotel chains offer standardized services and predictable experiences across diverse locations. While McDonaldization offers benefits like convenience, affordability, and consistency, critics argue it can lead to dehumanization, a reduction in quality where quantity is prioritized, a loss of local distinctiveness, and a feeling of an “iron cage” where rationalized systems increasingly constrain individuals. This ongoing process highlights the complex interplay between global economic forces and cultural landscapes.

McDonaldizing Media in the Digital Age

Media operates in an uncannily similar way to the fast-food industry, particularly through the lens of McDonaldization. Just as the automation of fast food—from freeze-dried French fries to pre-wrapped salads—attempts to lower a product’s marginal costs, thus increasing profits, media outlets increasingly seek to achieve a certain degree of consistency and replicability. This allows them to broadcast and sell the same or highly similar products throughout the world with minimal changes, maximizing reach and revenue. This principle is profoundly evident in the digital age, where streaming services and global content platforms leverage algorithms, data analytics, and standardized production workflows to deliver predictable content experiences to vast, diverse audiences.

However, the idea that the media unequivocally spreads a singular, dominant culture remains a subject of considerable controversy. In his influential book Cultural Imperialism, John Tomlinson argues that exported American culture is not necessarily imperialist in the traditional sense because it does not primarily seek to impose a cultural agenda through coercion. Instead, he posits that its primary driver is to generate revenue from the artistic and entertainment elements it can sell throughout the world. According to Tomlinson, “No one disputes the dominant presence of Western multinational, and particularly American, media in the world: what is doubted is the cultural implications of this presence (Tomlinson, 2001).” He suggests that audiences are not passive recipients but actively interpret and integrate global media into their local contexts, leading to cultural hybridization rather than outright replacement.

Despite Tomlinson’s nuanced perspective, the byproducts of dominant cultural exports, particularly from Western media, have undeniably spread worldwide. American cultural mores, such as the Western standard of beauty, have increasingly permeated global media, amplified by social media platforms and the pervasive reach of entertainment industries. As early as 1987, Nicholas Kristof wrote in The New York Times about a young Chinese woman who planned to have an operation to make her eyes look rounder, more like the eyes of Caucasian women. Western styles—”newfangled delights like nylon stockings, pierced ears and eye shadow”—also began to replace the austere blue tunics of Mao-era China. The pervasiveness of cultural influence proves difficult to track, however, as the young Chinese woman says that she wanted to have the surgery not because of Western looks but because “she thinks they are pretty (Kristof, 1987).” While this example is decades old, the influence persists, with global beauty industries still heavily promoting Eurocentric ideals. However, there is a growing counter-movement towards celebrating diverse beauty standards, often driven by social media influencers and more inclusive marketing campaigns.

The pervasiveness of cultural influence, however, proves difficult to track definitively. As the young Chinese woman in Kristof’s article stated, she wanted the surgery not because of Western looks per se but because “she thinks they are pretty.” This highlights the complex interplay between external influence and individual agency, where cultural elements are often adopted because they are perceived as desirable or aspirational within local contexts, rather than solely due to overt imposition. In the contemporary media landscape, the “McDonaldization” of content is also challenged by the rise of non-Western media powerhouses like K-Pop, Bollywood, and Nollywood, which demonstrate that cultural flows are increasingly multi-directional, leading to a dynamic global cultural mosaic rather than a simple one-way street of cultural dominance.

Cultural Imperialism, Resentment, and the Complexities of Global Conflict

Not everyone views the spread of American tastes and cultural products as a negative occurrence. Indeed, during the early 21st century, a significant strand of United States foreign policy was predicated on the idea that spreading freedom, democracy, and free-market capitalism through cultural influence around the world could encourage hostile countries, or those perceived as breeding grounds for extremism, to adopt American ways of living. The underlying hope was that such cultural integration would foster shared values, leading these nations to join the United States in the fight against global terrorism and tyranny. This approach, often termed “soft power,” aimed to achieve foreign policy goals through attraction and persuasion rather than coercion.

However, as history has shown, this plan did not succeed as simplistically as hoped, and its effectiveness remains a subject of ongoing debate and critical assessment. The idea that other local beliefs need to change, or that one cultural system is inherently superior and should be universally adopted, can provoke strong resentment rather than fostering alliance.

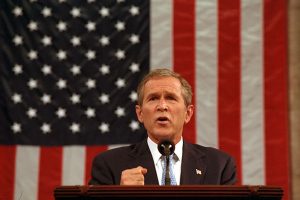

Speaking after the devastating attacks of September 11, 2001, then-President George W. Bush famously presented two seemingly simple ideas to the U.S. populace: “They [terrorists] hate our freedoms,” and “Go shopping (Bush, 2001).” These twin ideals of personal freedom and economic activity, often encapsulated in the “American Dream” narrative, frequently represent the prime cultural exports of the United States. Yet, for many cultures, these ideals may clash with deeply held communal values, religious traditions, or different understandings of societal well-being. The perception that these values are being imposed, rather than merely offered, can fuel anti-Western sentiment.

Academic discourse on the link between cultural imperialism and phenomena like radicalization or terrorism is complex and cautious, avoiding direct causal claims. While cultural grievances or perceived assaults on traditional ways of life can contribute to a sense of humiliation, injustice, or alienation, they are rarely the sole or primary drivers of terrorism. Instead, radicalization is understood as a multifaceted process influenced by a complex interplay of social, political, economic, historical, and psychological factors. These can include political oppression, economic inequality, lack of opportunity, historical grievances, discrimination, and the manipulation of ideology by extremist groups. Cultural factors, such as the perceived global dominance of Western commercial culture, which some traditional societies view as deeply offensive or contradictory to their values, can certainly be contributing elements to resentment. However, it’s crucial to recognize that terrorism emerges from a confluence of grievances and motivations, often exploited by leaders who provide a narrative that justifies violence.

In contemporary global dynamics, resistance to perceived American or Western cultural dominance takes many forms, ranging from cultural protectionist policies (like quotas for local media content) to the resurgence and global spread of non-Western cultural products (e.g., K-Pop, anime, Nollywood films). While these demonstrate a more multi-directional flow of culture, the underlying tension between globalizing forces and the preservation of local identities remains a critical aspect of international relations and cultural studies. The question of whether one culture should actively seek to transform another, even with purportedly benevolent intentions, continues to be a profound ethical and practical challenge in an interconnected world.

Freedom, Democracy, and Rock ’n’ Roll

The spread of culture works in mysterious ways, often defying simple explanations of imposition or unidirectional flow. Hollywood, for instance, probably does not operate with a master plan to export the American way of life globally and systematically displace local cultures. Similarly, American music may not necessarily be a direct progenitor of democratic government or economic cooperation in other nations. Instead, local cultures actively engage with and respond to the outside influences of global media and democratic ideals in a myriad of complex and dynamic ways.

Some local cultures around the world have adopted Western-style business models and media production techniques to such an extent that they have created their own vibrant hybrid cultures. India’s Bollywood film industry serves as a prime example of this phenomenon. Combining traditional Indian music and dance with elements of American-style filmmaking, Bollywood studios are incredibly prolific, consistently releasing a significantly higher number of significant films each year than the major Hollywood studios, often exceeding 1,500 to 2,000 films annually. India’s largest film industry expertly blends melodrama with elaborate musical interludes, where songs are typically lip-synced by actors but sung by popular playback singers. The widespread dissemination of these pop songs often occurs well before a movie’s release, strategically building hype and simultaneously entering multiple media markets, from radio and streaming to physical album sales. While Hollywood studios have attempted similar cross-promotional marketing tactics, Bollywood has arguably mastered the art of multi-platform integration. The music and dance numbers themselves often resemble cinematic forms of music videos, simultaneously promoting the soundtrack and adding spectacle and variety to the film’s narrative. These numbers also frequently feature a mix of different Indian national languages and a fusion of Western dance music with Indian classical singing, representing a distinct departure from conventional Western media formats (Corliss, 1996).

While the concept of cultural imperialism might suggest a one-way imposition causing resentment in many parts of the world, this idea often fails to account for the agency of local cultures fully. It assumes that native cultures are helpless against the perceived “crushing power” of American cultural influence. However, evidence suggests a more nuanced reality where local cultures actively adapt and reinterpret global media models, changing their methods to fit their corporate structures, aesthetic preferences, and cultural narratives, rather than simply adopting a foreign template wholesale. This process, often termed “cultural hybridization,” demonstrates that cultural exchange is a dynamic, two-way street. While economic and cultural aspects of globalization are interconnected, the evidence does not support a foreign power unilaterally crushing a native culture. Instead, it highlights a continuous process of negotiation, adaptation, and creative synthesis, where local cultures demonstrate remarkable resilience and innovation in shaping global media landscapes.