14.2 Ethical Issues in Mass Media

In the competitive and rapidly changing world of mass media communications, media professionals—overwhelmed by deadlines, bottom-line imperatives, and corporate interests—can easily lose sight of the ethical implications of their work. Ethics, in this context, refers to the moral principles that govern a person’s or group’s behavior, particularly concerning what is considered right or wrong in their professional conduct and its impact on society. It involves making reasoned judgments about how media content is created, disseminated, and consumed, and the profound responsibilities that come with shaping public discourse. As entertainment law specialist Sherri Burr pointed out, traditionally, “Because network television is an audiovisual medium that is piped free into ninety-nine percent of American homes, it is one of the most important vehicles for depicting cultural images to our population (Burr, 2001).” While broadcast television remains a significant force, this observation is even more pertinent today given the pervasive and multifaceted reach of digital media. Considering the immense influence that mass media, now encompassing television, streaming platforms, social media, and online news, has on cultural perceptions, public opinion, and individual attitudes, the creators and disseminators of media content face an increasingly complex landscape of ethical issues that demand careful and continuous consideration.

Stereotypes, Prescribed Roles, and Public Perception

The U.S. population has become increasingly diverse. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 estimates, the non-Hispanic White population makes up approximately 58% of the total, while Hispanic/Latino individuals account for about 20%, Black or African Americans for 13%, and Asians for 6%. Yet, in traditional network television broadcasts, significant publications, and other forms of mainstream mass media and entertainment, minority characters have historically been either underrepresented or depicted as heavily stereotyped, two-dimensional representations. For instance, while progress has been made, African Americans can still be typecast in roles that lean into tropes of criminality or exceptional athleticism, rather than showcasing a full spectrum of professions and personalities. Similarly, Latino characters have often been confined to roles such as gang members, domestic workers, or hyper-sexualized figures. In contrast, Asian characters have frequently been limited to stereotypes of academic overachievers, martial arts experts, or perpetual foreigners. These depictions not only lack depth but also reinforce harmful generalizations, often denying these communities opportunities to portray complex characters with a full range of human emotions, motivations, and behaviors. Meanwhile, the stereotyping of women, the LGBTQ+ community, and individuals with disabilities in mass media has also raised significant concerns. Women, despite increasing representation, still face portrayals that can be overtly sexualized, confined to domestic roles, or depicted as overly emotional or competitive. LGBTQ+ characters, while more visible, can fall into tropes like the “gay best friend” or face narratives centered solely on their identity struggles rather than their multifaceted lives. Individuals with disabilities are often subjected to “inspiration porn” narratives, depicted as objects of pity, or as bitter and isolated, rather than as fully integrated members of society with diverse experiences.

The word “stereotype” originated in the printing industry as a method of making identical copies, and the practice of stereotyping people mirrors this same principle: a system of identically replicating a simplified and often distorted image of an “other.” As seen in historical examples like D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, a film that notoriously relied on racial stereotypes to portray Southern Whites as victims in the American Civil War, stereotypes—especially those disseminated through mass media—become a powerful form of social control, shaping collective perceptions and individual identities. In American mass media, the non-Hispanic White male has historically represented the default viewpoint; they have often stood as the central figure of TV narratives and provided the dominant perspective on everything from trends to current events to politics. This pervasive centering has usually made “White maleness” an invisible category, giving the impression of representing the universal or “normal” human experience, thereby marginalizing other lived realities (Hearne).

In response to this persistent lack of authentic and diverse representation in mainstream media, independent creators from these underrepresented communities have increasingly leveraged digital platforms to form their niche markets and provide content that genuinely reflects their experiences. For example, African American creators have found success with web series like Issa Rae’s Awkward Black Girl, which later led to the HBO hit Insecure, offering nuanced portrayals of Black female friendships and professional lives. Asian American filmmakers are utilizing platforms like YouTube and Vimeo to produce independent films and web series that explore complex identity issues, such as Wong Fu Productions’ various short films and series. Latina creators are building significant followings on platforms like TikTok and Instagram, sharing cultural insights, comedic skits, and personal narratives, with influencers like Lele Pons and Salice Rose reaching millions by embracing their heritage and unique perspectives. For the LGBTQ+ community, web series such as Queer as Folk (though a mainstream production, it paved the way) and countless independent YouTube channels like those by Jessica Kellgren-Fozard (who also discusses her disabilities) offer diverse stories and build community. Similarly, individuals with disabilities are creating powerful content on platforms like YouTube and Instagram, with creators such as Shane Burcaw of “Squirmy and Grubs” and Lauren “Lolo” Spencer of “Sitting Pretty Lolo” sharing their lived experiences, challenging stereotypes, and advocating for accessibility. These independent voices are not only challenging traditional media narratives but also directly serving audiences who have long been starved for authentic portrayals, demonstrating a decisive shift in content creation and consumption dynamics.

The Unseen Fight: Breaking the Mold for Asian Talent in Hollywood

In the sprawling narrative of Hollywood, Asian actors have historically faced a narrow and often demeaning set of stereotypes, significantly limiting their opportunities and the complexity of the roles they could inhabit. From the early 20th century, depictions usually veered into the “Yellow Peril” trope, portraying Asian men as sinister, cunning villains or emasculated, subservient figures. In contrast, Asian women were frequently reduced to “Dragon Lady” archetypes or exotic, submissive “China dolls.” These one-dimensional portrayals were not just inaccurate; they severely constrained the artistic range of talented performers and perpetuated harmful societal biases. Early Hollywood even resorted to “yellowface,” casting white actors in Asian roles, further erasing authentic Asian presence on screen.

The emergence of martial arts films in the mid-20th century, particularly with the groundbreaking rise of Bruce Lee, marked a pivotal moment. Lee, with his unparalleled charisma, athleticism, and philosophical depth, shattered many existing stereotypes by presenting a powerful, masculine, and dignified Asian hero. His films like Fist of Fury and Enter the Dragon showcased a level of speed, agility, and realistic combat previously unseen in Western cinema, captivating global audiences. Lee became a symbol of pride for Asian communities worldwide, challenging the emasculated perception of Asian men and asserting a strong, defiant identity against colonial and racist narratives. His success opened doors, paving the way for other martial arts stars like Jackie Chan and Jet Li to gain international recognition.

However, Lee’s immense impact, while revolutionary, inadvertently led to a new form of typecasting. As Hollywood began to recognize the commercial appeal of martial arts, Asian actors often found themselves pigeonholed into “kung fu master” or “action hero” roles. While these characters offered a degree of strength and agency previously denied, they still represented a limited spectrum of human experience. The industry’s assumption became that if an Asian actor was cast, it was primarily for their martial arts prowess, regardless of the character’s narrative depth or emotional range. This created a “kung fu trap,” where talented actors struggled to break out of genre confines and portray everyday individuals, romantic leads, or complex dramatic figures. Even when Asian actors were cast in non-martial arts roles, they were often relegated to supporting characters, comedic relief, or “model minority” stereotypes—intelligent but lacking social skills, or hardworking but devoid of leadership qualities. This persistent typecasting reflected Hollywood’s reluctance to see Asian actors as versatile performers capable of embodying a full range of human emotions and experiences beyond a specific skill set.

This was the landscape that greeted many Asian actors, including Michelle Yeoh, as they transitioned from Asian cinema to Hollywood. Yeoh, a Malaysian actress, initially rose to fame in Hong Kong action cinema in the 1980s and 1990s, performing her breathtaking stunts in films like Police Story 3: Supercop and Yes, Madam!. Her background in ballet contributed to her remarkable grace and agility in fight choreography, establishing her as a formidable and unique action star. She gained international recognition with her role as a Bond girl in Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), where she was a formidable equal to Pierce Brosnan’s 007, and later achieved widespread critical acclaim for her role in Ang Lee’s wuxia masterpiece, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). While these roles showcased her incredible physical abilities, Yeoh consistently sought out more diverse characters, demonstrating her dramatic range in films like Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) and The Lady (2011), where she portrayed Burmese Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. Her role as the stern but loving matriarch Eleanor Young in Crazy Rich Asians (2018) further cemented her ability to command a screen outside of action sequences.

The culmination of Michelle Yeoh’s illustrious career and her relentless pursuit of diverse roles arrived with her starring performance in Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022). In this genre-bending film, Yeoh plays Evelyn Wang, a Chinese immigrant laundromat owner grappling with family dysfunction, financial woes, and an IRS audit, who suddenly discovers she must save the multiverse. While the film brilliantly incorporates her martial arts background into its chaotic, multiversal action sequences, it is fundamentally a deeply emotional and complex story about an ordinary woman, an immigrant mother, and her relationships. Yeoh’s portrayal of Evelyn was praised for its raw vulnerability, comedic timing, and profound emotional depth, allowing her to transcend the “action star” label she had long carried.

Her historic win of the Academy Award for Best Actress in 2023 for Everything Everywhere All at Once was a monumental moment for Asian representation in Hollywood. She became the first Asian person to win in a lead acting category in the Oscars’ 95-year history. In her acceptance speech, Yeoh famously declared, “For all the little boys and girls who look like me watching tonight, this is a beacon of hope and possibilities. This is proof that dreams… do come true. And ladies, don’t let anybody tell you that you are ever past your prime. Never give up.” Her win, alongside Ke Huy Quan’s Best Supporting Actor win for the same film, signaled a significant shift in Hollywood’s recognition of Asian talent, validating Asian narratives and demonstrating that complex, universally resonant stories can be told with predominantly Asian casts, moving beyond the historical confines of stereotypes and martial arts typecasting. While challenges remain, Yeoh’s triumph represents a decisive step towards a more inclusive and equitable cinematic landscape.

Minority Exclusion and Stereotypes

In the fall of 1999, when major television networks released their schedules for the upcoming programming season, a notable trend emerged. Of the 26 newly released TV programs, none depicted an African American in a leading role, and even the secondary roles on these shows included almost no racial minorities. In response to this glaring omission, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Council of La Raza (NCLR, now UnidosUS), an advocacy group for Hispanic Americans, organized protests and boycotts. Pressured—and embarrassed—into action, executives from the major networks made a fast dash to add racial minorities to their prime-time shows, not only among actors, but also among producers, writers, and directors. Four of the networks—ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox—added a vice president of diversity position to help oversee the networks’ progress toward creating more diverse programming (Baynes 2003).

Despite these initial changes and greater public attention regarding diversity issues, minority underrepresentation has remained a persistent challenge across all areas of mass media, even as the U.S. population has become increasingly diverse. As of 2023, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that non-Hispanic White individuals constitute approximately 58% of the population, while Hispanic/Latino individuals account for about 20%, Black or African Americans for 13%, and Asians for 6%. While there have been periods of progress, the overall trend in representation has often been slow and uneven.

Recent studies, such as the UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report 2024 (covering 2023 data), provide a more current snapshot. For streaming scripted shows, people of color achieved proportional representation for the first time in 2023, making up 44% of lead actors and 43% of the overall cast. This suggests that streaming platforms, driven by global and diverse subscriber bases, have been more responsive to demands for inclusive content. However, in broadcast scripted shows, people of color were only 26% of leads and 30% of the overall cast, and in films, they accounted for 25% of leads and 30% of the overall cast. This indicates that traditional media still lag in reflecting the nation’s diversity on screen. The problem extends significantly behind the scenes: in 2023, people of color made up only 28% of film directors, 25% of film writers, 30% of broadcast show creators, and 30% of streaming show creators. This continued lack of representation among producers, writers, and directors often directly affects the portrayal of minorities, leading to the perpetuation of racial stereotypes or a lack of nuanced storytelling.

Media professionals, as the creators and disseminators of content, hold a significant responsibility in shaping public perceptions. As media ethicist Leonard M. Baynes argued, “Since we live in a relatively segregated country…broadcast television and its images and representations are very important because television can be the common meeting ground for all Americans (Baynes).” This sentiment remains profoundly relevant in the digital age, where the media’s influence is even more pervasive. Historians and social scientists have drawn clear correlations between mass media portrayals of minority groups and public perceptions of these groups. For example, in 1999, after hundreds of complaints by African Americans that they could not get taxis to pick them up, the city of New York launched a crackdown, threatening to revoke the licenses of cab drivers who refused to stop for African American customers. When interviewed by reporters, many cab drivers blamed their actions on fears they would get robbed or asked to drive to dangerous neighborhoods—fears often fueled by negative media portrayals.

Racial stereotypes also continue to infiltrate news reporting. Journalists, editors, and reporters are still predominantly White. According to the 2022 Newsroom Diversity Survey by the News Leaders Association (NLA) and the Medill School of Journalism, people of color constituted 21.9% of newsroom employees in U.S. print and online newsrooms. While an improvement from earlier decades, this figure is still far from reflecting the U.S. population’s diversity, particularly in leadership and decision-making roles. In the news media, racial minorities can still be disproportionately cast in the role of villains or troublemakers, or their stories are framed through a lens of crime or poverty, which in turn shapes public perceptions about these groups. Media critics Robert Entman and Andrew Rojecki point out that images of African Americans on welfare, African American violence, and urban crime in African American communities “facilitate the construction of menacing imagery (Christians, 2005).” Similarly, studies have shown that when news outlets do cover Latino issues, the portrayals can often be negative or simplistic, focusing on immigration or crime rather than the community’s diverse contributions and concerns. Furthermore, journalists and reporters have been criticized for a tendency toward reductive presentations of complex issues involving minorities, such as the religious and racial tensions fueled by events like the September 11 attacks. By reducing these conflicts to “opposing frames”—simplified and often polarized perspectives—the news media can inadvertently help create a greater sense of separation between diverse communities and the dominant culture (Whitehouse, 2009).

Since the late 1970s, major professional journalism organizations in the United States—such as the Associated Press Media Editors (APME, now part of NLA), Newspaper Association of America (NAA, now News Media Alliance), American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE, also part of NLA), Society for Professional Journalists (SPJ), and Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA)—have consistently included greater ethnic diversity as a primary goal or ethical imperative. However, progress has been slow. ASNE had set 2025 as a target date to achieve parity between minority representation in newsrooms and U.S. demographics, a goal that, based on current trends, appears challenging to meet.

Because programming about, by, and for ethnic minorities in mainstream media has historically remained disproportionately low, many minorities continue to turn to niche publications, channels, and increasingly, digital platforms for sources of information and entertainment. These sources cover stories about racial minorities that legacy media outlets generally overlook and provide ethnic-minority perspectives on more widely covered news issues. Entertainment channels like BET (a 24-hour cable television station that offers music videos, dramas featuring predominantly Black casts, and other original programming created by African Americans) and Univision/Telemundo (major Spanish-language networks) provide the diverse programming that mainstream TV networks have often historically failed to deliver (Zellars, 2006). Beyond traditional broadcast, the digital landscape has seen an explosion of niche content, from podcasts and web series to independent streaming services (e.g., ALLBLK, Revry for LGBTQ+ content) and social media creators who cater specifically to diverse ethnic and racial groups. These platforms thrive because individuals within these groups control and create the content, ensuring authenticity and relevance. Although some critics argue that ethnic niche media might erode common ground or, in some instances, perpetuate their stereotypes, the immense popularity and growth of these media in recent years underscore their vital role in providing diverse perspectives and representation that mainstream media sources have historically struggled to offer consistently.

Building His Own Hollywood: Tyler Perry’s Blueprint for Black Media

Tyler Perry’s journey from a struggling playwright to a media mogul is a testament to his unique vision, entrepreneurial spirit, and unwavering commitment to an often-underserved audience. His contributions to mass media extend across theater, film, and television, fundamentally altering the landscape of Black representation and independent production in Hollywood.

Perry first cultivated a loyal following through his stage plays, particularly those featuring his iconic character, Madea. These plays, often touring the “Chitlin’ Circuit” of Black theaters, resonated deeply with audiences by blending humor, melodrama, and strong messages of faith, family, and overcoming adversity. This grassroots success laid the foundation for his formidable entry into film. In 2005, he adapted his play Diary of a Mad Black Woman into a feature film, which, despite a modest budget, achieved significant box office success. This marked the beginning of a prolific film career, with Perry writing, directing, and producing numerous movies, many of which also starred him as Madea. These films consistently drew large audiences, proving the commercial viability of content created by and for Black communities, a fact often overlooked by mainstream Hollywood.

One of Perry’s most significant contributions is his distinctive and highly efficient business model. Unlike traditional Hollywood productions that often involve lengthy development cycles and multiple layers of approval, Perry operates with remarkable speed and autonomy. He is known for writing, directing, and producing his projects with a lean crew and rapid turnaround times, a method that allows him to maintain creative control and keep production costs low while maximizing profits. This self-sufficient approach culminated in the establishment of Tyler Perry Studios (TPS) in Atlanta, Georgia. Opened in 2019 on a sprawling 330-acre former military base, TPS is one of the largest film production studios in the United States, making Perry the first African American to outright own a major film studio. This massive complex boasts twelve soundstages, each named after pioneering Black actors and actresses, along with numerous standing sets, including a replica of the White House. This ownership provides Perry with unparalleled creative freedom and the infrastructure to produce a vast amount of content independently.

Beyond his projects, Perry has played a crucial role in creating opportunities for Black talent, both in front of and behind the camera. His studios have become a significant hub for film and television production, not just for his work but also for major Hollywood productions (e.g., Marvel films, The Walking Dead). This has translated into consistent employment for countless Black actors, writers, directors, and crew members in an industry historically known for its barriers to entry for people of color. Perry has often spoken about his commitment to building wealth within the Black community, asserting that he has helped create more Black millionaires than any studio in Hollywood combined. His initiatives, such as the Tyler Perry Studios Dream Collective, further aim to nurture and support emerging filmmakers from underrepresented communities, providing grants, training, and mentorship.

Perry’s work, while commercially successful and culturally impactful, has also been the subject of considerable critical debate. Some critics, including filmmaker Spike Lee, have accused his work of perpetuating negative stereotypes, particularly regarding Black women, and relying on simplistic narratives or melodrama. The Madea character, in particular, has drawn both immense adoration from fans who see her as a strong, relatable matriarch and criticism for potentially reinforcing “mammy” archetypes or “buffoonery.” However, Perry has consistently defended his artistic choices, emphasizing that he creates content for an audience that often feels overlooked by mainstream media, and that his characters resonate deeply with their lived experiences, offering messages of hope, resilience, and faith. The reception of his films often highlights a significant divide between audience appreciation (especially within the Black community) and critical reviews, underscoring different priorities in evaluating media.

In recent years, Perry has expanded his reach into the streaming landscape, forging significant content deals with platforms like BET+ and OWN (Oprah Winfrey Network). His prolific output, including popular series like Sistas, The Oval, and House of Payne, has been instrumental in the growth and success of these platforms, solidifying his position as a powerhouse in television production. He has produced hundreds of episodes for BET and BET+, ensuring a steady stream of Black-centered narratives for a global audience.

Tyler Perry’s contributions to mass media are undeniable. He built an empire by understanding and serving an audience that Hollywood largely ignored, demonstrating the immense commercial power of authentic Black storytelling. Through his self-funded productions and the establishment of Tyler Perry Studios, he has not only created a vast body of work. But also, he has provided unprecedented opportunities for Black talent, challenging traditional industry structures and paving the way for greater diversity and ownership in entertainment. While his artistic style may remain a subject of debate, his impact on representation and independent media production is a significant and enduring legacy.

Femininity in Mass Media

In the classic ABC sitcom The Donna Reed Show (1958–1966), actress Donna Reed portrayed a stay-at-home mother who filled her days with household chores, cooking, decorating, and community activities, all while impeccably dressed in pearls, heels, and stylish dresses. While such a traditional portrayal of femininity undoubtedly feels dated to modern audiences, stereotyped gender roles, though evolving, continue to thrive in various forms of mass media.

Women are still frequently represented in roles that, even if not overtly subordinate, often align with traditional feminine attributes—emotional, nurturing, domestic, or sweet-natured. Conversely, if women deviate from these norms, they may still be portrayed as “unattractively masculine,” overly aggressive, crazy, or cruel. In TV dramas and sitcoms, women continue to be disproportionately cast in roles such as mothers, nurses, secretaries, and homemakers. However, there’s a growing presence of women in professional and leadership roles. By contrast, men in film and television appear in their home environment less frequently than women. They are generally characterized by attributes such as dominance, aggression, action, physical strength, and ambition (Chandler). While there’s an increasing push for more nuanced male characters, traditional masculinity often remains the default. Similarly, in legacy news media, men predominantly feature as authorities on specialized issues like business, politics, and economics. At the same time, women reporters have historically been more likely to cover “softer” news such as natural disasters or domestic violence—though this trend is slowly shifting as more women occupy diverse beats and leadership positions (Media Awareness Network).

Not only does the traditionally White male perspective often get presented as the standard, authoritative one, but the media itself frequently produces content that embodies the male gaze. The “male gaze,” a concept coined by feminist film critic Laura Mulvey in 1975, refers to the way women and the world are depicted in visual arts and literature from a masculine, heterosexual perspective, often presenting women as sexual objects for the pleasure of a male viewer. This involves the camera (and thus the audience) lingering on female bodies, focusing on their physical appearance, and framing their narratives and value primarily through their attractiveness to men. Media commentator Nancy Hass’s observation that “shows that don’t focus on men have to feature the sort of women that guys might watch” succinctly captures this pervasive dynamic (Media Awareness Network). Feminist critics have long expressed concerns about how film, television, and print media define women by their sexuality, often at the expense of their intelligence, leadership qualities, or multifaceted personalities.

Inundated by images that conform to unrealistic beauty standards, women and girls can internalize at an early age that their value depends significantly on their physical attractiveness. This pressure is exacerbated by media portrayals featuring models who appear unrealistically thin (studies have shown models can be 23 percent thinner than the average woman), and the widespread use of digital editing programs like Photoshop to conceal perceived flaws and blemishes. This constant exposure contributes to body dissatisfaction and, in severe cases, has been correlated with the routine diagnosis of eating disorders in girls at increasingly younger ages, sometimes as early as eight or nine. Furthermore, ageism remains a significant issue for women in media; while the majority of female characters on television are often in their 20s and 30s, the percentage of female characters plummets significantly in their 40s and beyond. In contrast, male characters continue to be prominently featured at older ages. This pressure to embody a youthful ideal often leads older actresses to undergo surgical enhancements to maintain their careers (Derenne & Beresin, 2006). Even respected news figures, like former TV news host Greta Van Susteren, faced scrutiny over their appearance and perceived need for “makeovers” in a visually driven industry.

In addition to the prevalence of gender stereotypes, a disproportionate ratio of men to women has historically worked in the mass media, both in front of and behind the scenes. While women slightly outnumber men in the general population, their representation in creative and leadership roles has lagged. According to the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film’s “Celluloid Ceiling” report for 2024 (covering 2023 data), women comprised only 16% of directors and 20% of writers on the top 250 films. For broadcast and streaming television series (2023-2024), women accounted for 23% of creators, 19% of directors, and 33% of writers. These figures, while showing some incremental gains over decades, still indicate a significant disparity. Communications researcher Martha Lauzen’s argument remains highly relevant: “When women have more powerful roles in the making of a movie or TV show, we know that we also get more powerful female characters on-screen, women who are more real and more multi-dimensional (Media Awareness Network).”

The #MeToo movement, which gained significant momentum in 2017 following revelations of widespread sexual harassment and assault in Hollywood and beyond, has had a profound impact on discussions surrounding gender in media. By empowering survivors to share their stories and holding influential individuals accountable, the movement forced a reckoning with deeply entrenched patriarchal structures and abusive workplace cultures. In the media industry, #MeToo led to the downfall of numerous prominent figures, from executives and producers to actors and journalists, who had previously operated with impunity.

The movement has spurred significant shifts, including increased awareness of gender-based discrimination and harassment, a greater emphasis on workplace safety and accountability, and a renewed push for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. While progress is ongoing and challenges persist, #MeToo has undeniably contributed to a more critical examination of gender dynamics on screen and behind the scenes, encouraging the creation of more nuanced female characters, promoting female storytellers, and fostering environments where women feel safer to work and speak out. It has highlighted the interconnectedness of representation, power, and ethical conduct in the mass media.

Sexual Content in Public Communication

(Lifetime: na (–work for hire for Andrew Jergens Co, Cincinnati), 1916-skin-touch-soap-ad, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons.

The representation of sex in entertainment presents a complex web of ethical considerations, prompting crucial discussions around artistic intent versus gratuitousness and exploitation. The challenge lies in discerning whether sexual acts depicted serve a narrative purpose, develop characters, or explore profound themes, or if they are merely included for shock value, titillation, or to exploit performers. This distinction is vital for maintaining ethical standards within the industry.

Beyond the portrayal of the acts themselves, the ethics of sex in entertainment also extend to representation and societal impact. A significant concern is whether these depictions reinforce negative stereotypes, perpetuate harmful power dynamics, or normalize exploitation. For instance, if content consistently portrays women as mere objects of desire or in subordinate roles, it can subtly contribute to broader societal inequalities. This concern has led to evolving industry standards and practices, notably the widespread adoption of intimacy coordinators. These professionals are now common on film and television sets, working to ensure the safety, comfort, and agency of actors during scenes involving nudity, simulated sex, or intimate contact. Their role is to choreograph scenes with consent, establish boundaries, and ensure that the artistic vision is met without exploitation or discomfort for the performers.

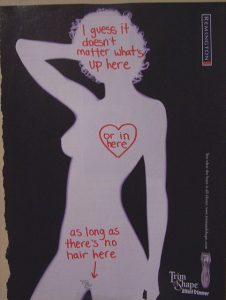

In the realm of public communication, creators across all forms of media universally acknowledge that sexual content—whether explicitly displayed, subtly hinted through innuendo, or overtly presented—is a powerful magnet for audience attention. The enduring advertising cliché, “Sex sells,” manifests across the mass media through an inexhaustible array of products linked to erotic imagery or innuendo, from cosmetics and cars to vacation packages and beer. Most often, this sexualized advertising content features the female body, in part or in whole, in provocative or suggestive poses, sometimes with little or no logical connection to the product being sold. By linking these disparate elements, advertisers effectively market the concept of desire itself, leveraging primal human attraction.

Beyond consumer goods, sex also sells media content. Music videos continue to promote artists and their music with highly suggestive dance moves, often performed by women in scanty clothing, designed to maximize viewership and virality. Movie trailers frequently flash brief images of nudity or passionate kissing to tantalize audiences with promises of more mature content. In video games, while there has been an evolution towards more diverse and less hyper-sexualized female character designs, the legacy of characters like the early iterations of Lara Croft from Tomb Raider, with her exaggerated, “Barbie-doll” figure and tightly fitted clothes, persists in the cultural consciousness. Partially nude models still grace the covers of both men’s and women’s magazines, such as Maxim, Cosmopolitan, and Vogue, where cover lines promise titillating tips, gossip, and advice on bedroom behavior, even as digital platforms and social media influencers increasingly dominate this space (Reichert & Lambiase, 2005).

Historically, filmmakers in the 1920s and 1930s also attracted audiences with content considered scandalous for their era. Before the strict 1934 Hays Code, which placed significant restrictions on “indecent” content in movies, films featured erotic dances, male and female nudity, references to homosexuality, and sexual violence. D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance includes scenes with topless actresses, as does Ben Hur. In Warner Bros.’ Female, the leading lady, the head of a major car company, engaged in sexual exploits with her male employees—a storyline that would never have passed the Hays Code a year later (Morris, 1996). Paramount Pictures even withdrew its 1932 comedy Trouble in Paradise from circulation after the institution of the Hays Code because of its frank discussion of sexuality. Similarly, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), which featured a prostitute as one of its main characters, was banned under the code (Hauesser, 2007). In the 1960s, as the sexual revolution led to increasingly permissive attitudes toward sexuality in American culture, the MPAA rating system replaced the Hays Code. This rating system, designed to warn parents about potentially objectionable material in films, effectively allowed filmmakers to include sexually explicit content without fear of widespread public protest, leading to a greater frequency of such content in cinema. The eventual dismantling of the Code and the advent of the MPAA rating system were ethical shifts reflecting changing societal norms and a move towards viewer discretion.

Similarly, while a significant moment for Black representation in cinema, some Blaxploitation films from the 1970s present ethical dilemmas regarding sexual depiction. While empowering in their portrayal of strong Black protagonists, some films were criticized for exploiting Black female sexuality through gratuitous nudity and scenes that reinforced problematic stereotypes about hypersexuality or violence against women, particularly when such scenes felt unnecessary to the plot and served primarily for titillation. This highlights the ongoing tension between artistic freedom, commercial viability, and the ethical responsibility of representation.

Many media critics do not lament the mere appearance of sex in the media, but instead its often unrealistic and problematic portrayal (Galician, 2004). This can be harmful to society, as mass media act as important socialization agents, informing people about the norms, expectations, and values of their culture. Sex, as many films, TV shows, music videos, and song lyrics present it, often occurs frequently and casually, divorced from emotional depth or realistic consequences. Rarely do these media portrayals adequately address potential risks like sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or unwanted pregnancies. Furthermore, actors and models depicted in sexual relationships in the media almost universally conform to narrow ideals of beauty—thinner, younger, and conventionally attractive characteristics than the average adult. This creates unrealistic expectations about the necessary ingredients for a satisfying sexual relationship and contributes to body image issues.

Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” music video from 1989 sparked immense controversy and ethical debate, particularly regarding its blending of religious iconography with overt sexual themes. The video featured Madonna dancing provocatively in a church, stigmata, and kissing a Black saint, leading to accusations of blasphemy and sexualizing religious symbols. Pepsi, which had a sponsorship deal with Madonna for the song, faced boycotts and ultimately pulled its advertising, illustrating the ethical tightrope corporations walk when associating with controversial artistic expressions that challenge societal norms, especially concerning sex and sacred imagery. The moral debate centered on artistic freedom versus religious offense and potential exploitation of religious symbols for commercial gain.

Beyond the Joystick: Unmasking Online Misogyny in Gaming

The broader ethical discussion surrounding sex in the media encompasses a wide range of issues, from the portrayal of sexuality and consent to the exploitation of performers and the impact of sexualized content on societal norms. However, the intersection of sex, gender, and online harassment dramatically exploded into public consciousness with #Gamergate, a contentious online movement that began in 2014. While ostensibly centered around ethics in video game journalism, this phenomenon quickly devolved into widespread, often vicious, attacks on women in the gaming industry and online media.

At the heart of the initial controversy was game developer Zoe Quinn. She became a primary target when an ex-boyfriend falsely accused her of using sex to promote her games and influence journalists, as well as attempting to “feminize” the world of gaming. These accusations, though unsubstantiated and quickly debunked by many, ignited a firestorm. The disproportionate and venomous attacks directed at Quinn, rather than the journalists supposedly implicated in the initial “ethics” accusations, starkly revealed the deep-seated misogynistic undercurrents within a vocal segment of the gaming community. This wasn’t merely a debate about journalistic standards; it was a furious backlash against women gaining visibility and influence in a space traditionally dominated by men, fueled by a perceived threat to a male-centric gaming identity.

The harassment tactics employed during Gamergate were severe and often terrifying. Targets, including Quinn, prominent feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian, and game developer Brianna Wu, faced relentless online abuse. This included doxing (publishing private information like home addresses), swatting (making false reports to emergency services to provoke an armed police response at a victim’s home), constant death threats, graphic rape threats, and sustained campaigns of online intimidation. The sheer volume and intensity of this harassment created a hostile environment, forcing many women to fear for their safety and, in some cases, to leave their homes, abandon their careers, or seek police protection. The pretense of “ethics” quickly evaporated, exposing a campaign rooted in misogyny and a desire to exclude women from gaming culture.

In response to this onslaught, groups dedicated to exposing and combating the violent messages and pervasive harassment directed toward female gamers and developers emerged. These groups, often labeled derogatorily as #SJW (Social Justice Warriors) by Gamergate proponents, sought to advocate for greater inclusivity and safety in online spaces, pushing for a more diverse and welcoming gaming community. Gamergate itself has been broadly described as a “culture war” over the diversification of gaming culture, artistic recognition, feminism’s role in video games, social criticism within gaming narratives, and the very social identity of gamers. While supporters claimed it was a social movement focused on journalistic integrity, its lack of clearly defined goals, a coherent message, or official leaders made it difficult to precisely define and often served as a convenient shield for widespread harassment.

Regardless of its stated intentions, Gamergate left an indelible mark. It prompted figures both within and outside the gaming industry to focus seriously on developing methods to address online harassment, minimize harm, and prevent similar events. This led to increased awareness of online abuse, the implementation of stronger community guidelines on platforms, and a greater emphasis on diversity and inclusion initiatives within game development studios and media organizations. In retrospect, Gamergate has also been widely viewed as a contributing factor to the rise of the alt-right and other far-right online movements, due to its tactics, its targeting of perceived “cultural elites,” and its cultivation of an aggrieved, anti-establishment online identity. The incident remains a stark reminder of how discussions around sex and gender in media can quickly escalate into real-world harm, particularly in the volatile and often anonymous landscape of online communities.

The adverse effects these unrealistic portrayals have on women particularly concern social psychologists, as women’s bodies frequently symbolize the primary means of introducing sexual content into media targeted at both men and women. Media activist Jean Kilbourne points out that “women’s bodies are often dismembered into legs, breasts, or thighs, reinforcing the message that women are objects rather than whole human beings.” Adbusters, a magazine that critiques mass media, particularly advertising, frequently highlights the sexual objectification of women’s bodies in its spoof advertisements, underscoring how advertising often sends unrealistic and harmful messages about women’s bodies and sexuality. Additionally, many researchers note that in women’s magazines, advertising, and music videos, women often receive the implicit—and sometimes explicit—message that their primary concern should be attracting and sexually satisfying men (Parents Television Council). Furthermore, some studies suggest that the increase in entertainment featuring sexual violence may negatively affect how young men behave toward women (Gunter, 2002).

Young women and men are especially vulnerable to the effects of media portrayals of sexuality. Psychologists have long noted that adolescents and children obtain much of their information and many of their opinions about sex through TV, film, and, increasingly, online media, including social media platforms. Research consistently indicates a high exposure to sexual content among adolescents, which can shape their attitudes toward sex and, in some cases, correlate with earlier initiation of sexual activity (Collins, et. al., 2004). Jean Kilbourne’s argument remains poignant: sex in American media “has far more to do with trivializing sex than with promoting it. We are offered a pseudo-sexuality that makes it far more difficult to discover our own unique and authentic sexuality (Media Awareness Network).”

The #MeToo movement, which gained significant global momentum in 2017, profoundly impacted how sexual content is created and managed within the entertainment industry. By exposing widespread patterns of sexual harassment, assault, and abuse of power, #MeToo forced a critical re-evaluation of long-accepted industry practices. It brought to light the vulnerability of actors, particularly women and marginalized individuals, during the filming of intimate scenes, where power imbalances could be exploited.

In direct response to these revelations and the subsequent demand for safer and more ethical working environments, the role of the intimacy coordinator emerged and rapidly became an industry standard. An intimacy coordinator is a trained professional who acts as a liaison between actors and production, ensuring consent, safety, and clear communication during the choreography and filming of nudity, simulated sex, and other intimate scenes. They work with directors to realize their creative vision while protecting actors’ physical and emotional boundaries, ensuring that consent is ongoing and informed. This role, now often mandated by major unions like SAG-AFTRA, aims to professionalize the handling of intimate content, minimize discomfort, prevent exploitation, and create a more respectful and equitable set culture. The rise of intimacy coordinators is a tangible outcome of the #MeToo movement’s influence, demonstrating a collective industry effort to address past harms and establish new ethical benchmarks for sexual content in media production.