14.3 News Media and Ethics

Now more than ever, in an era dominated by a relentless 24/7 news cycle and the pervasive influence of social media platforms, audiences expect news delivery to arrive instantaneously. Journalists and news agencies face unprecedented pressure to break stories rapidly, driven by the intense competition from traditional outlets, digital-native competitors, and even citizen journalists. With this amplified demand for speed, upholding the foundational standards of accuracy, fairness, and thorough verification becomes increasingly challenging.

This constant push-pull raises a critical question: What wins when ethical responsibility and bottom-line concerns conflict in the fast-paced world of news? As columnist Ellen Goodman observed decades ago, there has always been a fundamental tension in journalism between being first and being right. Her argument that “in today’s amphetamine world of news junkies, speed trumps thoughtfulness too often” (Goodman, 1993) rings even truer in our current digital landscape, where the viral spread of unverified information can outpace careful reporting. The proliferation of user-generated content and the race to capture clicks and engagement often prioritize immediacy over meticulous fact-checking, contributing to the spread of misinformation and disinformation. When reading the following sections, consider whether Goodman’s prescient assessment of the news media’s state continues to resonate in today’s hyper-connected, information-saturated environment.

Immediate News Delivery

In 1916, a momentous event unfolded in the offices of The New York American. Technicians broadcast the first-ever breaking news coverage of an event: the results of the presidential election between Woodrow Wilson and Charles Evans Hughes. This historic broadcast marked a significant shift in how news was delivered, as American homes had previously received the news once (or twice) per day in the form of a newspaper, with coverage lagging a day or more behind the actual incidents it reported. The advent of radio offered something newspapers could not: the immediate transmission of special events, a feature that would profoundly shape the future of news delivery (Govier, 2007).

For decades, the public turned to family radio for the latest news coverage. All of that changed, however, in 1963 with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. CBS correspondent Dan Rather took television audiences live to “the corner window just below the top floor, where the assassin stuck out his .30-caliber rifle,” and for the first time, people could see an event nearly as it occurred. This signified the beginning of round-the-clock news coverage, and the American public, while still relying on print news for detailed coverage, came to expect greater immediacy of major event reporting through TV and radio broadcasts (Holguin, 2005).

Today, with the widespread availability of internet news and the pervasive influence of social media, instant coverage has become the norm rather than the exception. The internet has largely replaced traditional TV and radio as the primary source for obtaining immediate information for many demographics. Visitors to major news sites can often access breaking stories, live video streams, and in-depth reports long before they air on linear television or are published in print. Home pages for major news-delivery sites, news tickers, live video streams, blogs, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, Instagram, and a host of other digital platforms ensure that news—and often rumors or misinformation—circulate within minutes of an event’s occurrence. Additionally, with smartphone applications for outlets like The New York Times and USA Today, people can receive real-time updates, alerts, and access to the latest news coverage from almost anywhere, making news consumption a constant, on-demand experience.

The development of the internet as a source of free and immediate access to information has fundamentally democratized the news media. It has forever changed the structure of news delivery, compelling traditional media outlets, such as newspapers, television, and radio, to adapt and diversify to compete for a share of the fragmented audience. As Jeffrey Cole, director of the Center for Digital Communication, aptly put it, “For the first time in 60 years, newspapers are back in the breaking news business.” Online, newspapers can now compete with broadcast media for immediate coverage by posting articles on their home pages as soon as they are written, and supplementing these articles on their websites with multimedia content, including audiovisuals and interactive graphics. The era of single-medium newsrooms with predictable deadlines has given way to a more agile, multi-platform, and accessible news landscape (USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, 2009).

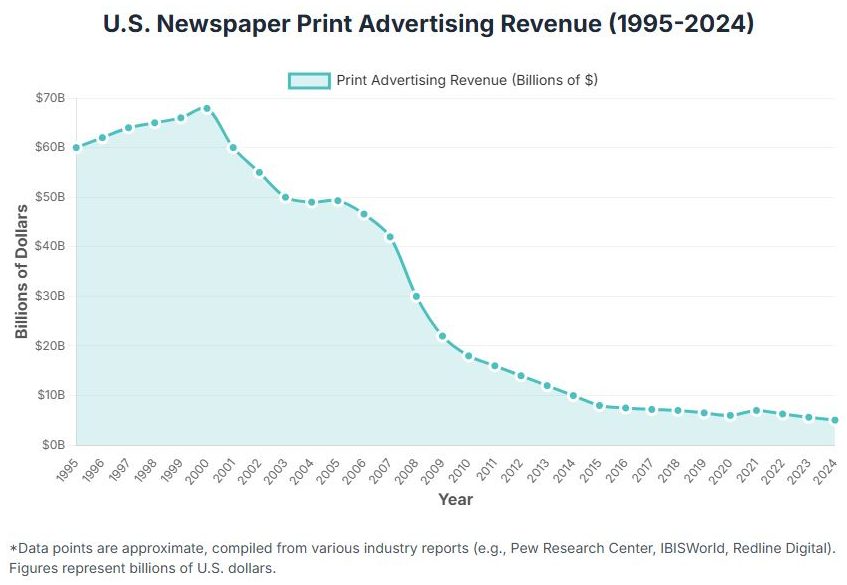

Not only have traditional news media companies restructured their approach, but news consumers have also dramatically changed the way they access information. Increasingly, audiences demand news on demand; they want to get news when they want it, from a variety of sources, and often tailored to their interests. This shift has had a significant and frequently challenging effect on media revenues. News aggregators, such as Yahoo! News and Google News, which compile news headlines from various legacy news organizations, remain popular information sources. While these websites typically don’t hire reporters to produce original news stories, they still attract substantial online traffic. Moreover, many subscribers to print newspapers and magazines have canceled their subscriptions because they can get more current information online, often at no direct cost. Print advertising revenue continues its steep decline. For example, in the early 2000s, The San Francisco Chronicle reported losing tens of millions in classified advertising to free online options like Craigslist, a trend that decimated a once-lucrative revenue stream for newspapers nationwide.

This loss of traditional revenue has become a critical problem. While newspapers and magazines generate some income from advertisements on their websites and, increasingly, from digital subscriptions, this income often does not fully compensate for the lost readership and print advertising dollars. The financial support base for many news organizations has dwindled, forcing widespread restructuring and scaling down. Newsrooms across the country have experienced significant budget cuts and staff reductions. For instance, between 2008 and 2020, newsroom employment in the U.S. fell by more than 50%, a stark indicator of the industry’s financial strain.

Reduced budgets, combined with increased pressure for immediacy, have significantly altered the way information is reported and disseminated. Newsrooms have often asked their staff to prioritize producing “first accounts” quickly to meet the demands of multiple platforms. This can mean that more resources are allocated to distributing information rapidly across various channels than to the painstaking process of gathering and thoroughly verifying it. Once a source releases news online, it spreads quickly, and other organizations scramble to release their accounts to keep up, often leaving staff less time for in-depth fact-checking, editing, and contextualization. Both professional news organizations and non-professional sources, such as blogs and social media accounts, can then quickly add their commentary, further complicating the information landscape. This shift in focus and resource allocation has raised serious concerns about the overall quality, accuracy, and depth of news reporting in the current media environment.

As a result of this restructuring, certain stories may be distributed, replayed, and commented on excessively, often becoming viral sensations. In contrast, other crucial stories may go unnoticed, and the kind of in-depth, investigative coverage that would unearth more facts and context is neglected. This has led some industry professionals to express deep anxiety over the future of the news industry. The Center for Excellence in Journalism has characterized the news industry today as “more reactive than proactive.” While some critics, like journalist Patricia Sullivan, might lament that “almost no online news sites invest in original, in-depth and scrupulously edited news reporting,” this statement needs nuance. While many struggle, a growing number of digital-native news organizations (e.g., ProPublica, The Marshall Project) and major legacy outlets that have successfully pivoted to digital-first models (e.g., The New York Times, The Washington Post) do invest heavily in investigative and in-depth journalism, often supported by digital subscriptions and philanthropic funding.

Nonetheless, in-depth journalism remains an expensive and time-consuming venture that many online news sites, faced with uncertain revenue streams and a relentless consumer demand for real-time news updates, have shown reluctance to bankroll extensively. News organizations, already strapped for funds, know they must cater to public needs, which means delivering news quickly and accurately. The death of pop-music icon Michael Jackson on June 25, 2009, serves as a classic illustration of this dynamic: news of his death hit cyberspace via celebrity gossip website TMZ by 2:44 p.m. PST, soon spreading nationwide via Twitter. Legacy news sources, wary of the sourcing, hesitated. The Los Angeles Times, for instance, waited to confirm the news and didn’t publish the story on its website until 3:15 p.m., by which time, thanks to the speed of social media, the star’s death was already “old news” to many (Collins & Braxton, 2009). This event highlighted the dramatic shift in the competitive landscape and the ongoing tension between speed and accuracy in modern journalism.

Funding Truth: ProPublica and the Philanthropic Future of Journalism

In an era where traditional newsrooms grapple with dwindling resources and the relentless demands of the 24/7 news cycle, ProPublica stands as a beacon for the resurgence of in-depth, investigative journalism. Launched in 2008, this digital-native, non-profit news organization has not only successfully carved out a unique and impactful niche. But it has also become a leading example of how philanthropic funding can sustain rigorous, public-interest reporting in the digital age.

ProPublica was the brainchild of Herbert and Marion Sandler, San Francisco-area billionaires and former chief executives of Golden West Financial Corporation, who committed an initial $10 million annually to the venture. They hired Paul Steiger, the highly respected former managing editor of The Wall Street Journal, to lead the organization as its founding editor-in-chief. Their mission was clear: to produce investigative journalism with “moral force,” shining a light on abuses of power and betrayals of public trust by government, business, and other institutions. This commitment to deep, often time-consuming investigations sets ProPublica apart from many news outlets increasingly pressured to prioritize speed and clicks.

From its inception, ProPublica adopted a digital-first model, recognizing the internet’s potential for wide dissemination and innovative storytelling. Unlike traditional newspapers that were struggling to adapt their print-centric operations to the web, ProPublica was built for the digital environment. Its strategy involved making its meticulously reported stories freely available to other news organizations, encouraging them to republish the content on their platforms. This collaborative approach, a significant departure from competitive, proprietary models, allowed ProPublica‘s work to reach vast audiences through partnerships with prominent outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, and various local news organizations. This strategy not only maximized the impact of their investigations but also helped to fill a growing void in investigative reporting as many traditional newsrooms cut back on such expensive endeavors.

ProPublica‘s funding model is primarily rooted in philanthropy. While the initial substantial commitment from the Sandler Foundation provided a crucial launchpad, the organization has since diversified its donor base, receiving significant support from other major foundations such as the Knight Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, and Ford Foundation, as well as thousands of individual donors. This philanthropic backing allows ProPublica‘s journalists the time and resources needed for extensive research, data analysis, and on-the-ground reporting—work that often takes months or even years to complete. While ProPublica also accepts advertising and sponsorship on its website, these revenue streams are secondary, ensuring that the editorial independence and mission-driven focus remain paramount, unswayed by commercial pressures. The organization prides itself on transparent financial reporting, demonstrating how the vast majority of its funding goes directly into producing its award-winning journalism.

The impact of ProPublica‘s work on journalism has been profound. It has not only demonstrated that a non-profit model for investigative journalism can be sustainable but has also inspired the creation of numerous other non-profit newsrooms across the United States, such as The Texas Tribune and The Marshall Project. ProPublica measures its success not by clicks or ad revenue. Still, by the tangible “impact” its stories have—whether leading to policy changes, resignations of corrupt officials, new legislation, or increased public accountability. This focus on real-world change has resonated deeply with philanthropists and readers alike, creating a virtuous cycle where impactful journalism attracts more funding, enabling more impactful journalism.

ProPublica has garnered numerous accolades, including multiple Pulitzer Prizes, a testament to the quality and significance of its reporting. Among its most profound stories are “The Deadly Choices at Memorial,” an investigation co-published with The New York Times Magazine in 2009, which exposed harrowing decisions made by medical staff during Hurricane Katrina and earned a Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. Another impactful piece, “An Unbelievable Story of Rape” from 2015, detailed police mishandling of a rape investigation, leading to a Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting and inspiring a Netflix series. The “Machine Bias” series in 2016 investigated algorithmic bias in the criminal justice system, sparking national debate. More recently, the “Secret IRS Files” in 2021, based on leaked data, revealed how the wealthiest Americans pay minimal income tax, earning ProPublica another Pulitzer Prize. The “Friends of the Court” series in 2023 exposed undisclosed luxury trips and gifts received by Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, leading to significant ethical scrutiny.

Through these and countless other investigations, ProPublica has not only held powerful institutions accountable but has also demonstrated the enduring value and necessity of deep, independent journalism in a healthy democracy. Its model serves as a vital blueprint for the future of news, proving that rigorous, public-interest reporting can thrive with dedicated support and a commitment to impact.

Social Responsibility of News Media

The social responsibility of news media is a foundational principle for democratic societies, often articulated as the “vital information premise.” As expressed by organizations like the Committee of Concerned Journalists, the central purpose of journalism is “to provide citizens with accurate and reliable information they need to function in a free society.” This widely accepted principle serves as the ethical bedrock for news reporting, guiding journalists in their crucial role within the public sphere (Iggers, 1999).

A primary tenet of this social responsibility is to present news stories that genuinely inform and serve the needs of citizens. This necessitates unwavering commitment to accuracy and truthfulness. Journalists are ethically bound to verify facts meticulously before disseminating them. As the Committee of Concerned Journalists asserts, “Accuracy is the foundation upon which everything else is built—context, interpretation, comment, criticism, analysis, and debate.” In an age saturated with information, reliable news sources are more essential than ever for citizens to navigate complex societal issues and make informed decisions. Furthermore, while news organizations have legitimate professional responsibilities toward advertisers and shareholders, their paramount commitment must always remain to the general public. This means journalists must report facts truthfully and without omission, even if doing so conflicts with the commercial interests of advertisers, the financial interests of shareholders, or the personal preferences of influential figures.

Presenting issues fairly is another critical component. This demands not only factual accuracy but also a rigorous avoidance of favoritism toward any organization, political group, ideology, or other agenda. Professional bodies like the Society of Professional Journalists stipulate that journalists should refuse gifts and favors and avoid political involvement or public office if these actions could compromise their journalistic integrity or the public’s perception of their impartiality (Society of Professional Journalists). Additionally, journalists are expected to resist the temptation to inflate stories for sensation, a growing challenge in the attention economy. Transparency about their sources of information is also vital, allowing the public to assess credibility and, where appropriate, investigate issues further independently. While every journalist possesses a unique perspective, news organizations and individual reporters must strive to maintain a clear distinction between objective news reports and subjective editorial content, even as digital platforms increasingly blur these lines (American Society of News Editors, 2009). The goal is to provide a comprehensive and balanced view, avoiding “false balance” where disproportionate weight is given to fringe viewpoints.

Skepticism Required: The Carlson Ruling and the Shifting Sands of Media Truth

In a notable legal battle that illuminated the fine line between news and opinion in cable television, former Playboy model Karen McDougal filed a defamation lawsuit against Fox News and its then-prominent host, Tucker Carlson. The suit stemmed from a December 2018 segment on Tucker Carlson Tonight, where Carlson discussed the “catch-and-kill” scheme involving payments made to McDougal and adult film actress Stormy Daniels to silence their alleged affairs with Donald Trump before the 2016 presidential election.

During the broadcast, Carlson stated, “Remember the facts of the story; these are undisputed. Two women approached Donald Trump and threatened to ruin his career and humiliate his family if he didn’t give them money. Now, that sounds like a classic case of extortion.” McDougal vehemently denied ever threatening Trump or engaging in extortion and argued that Carlson’s characterization of her actions was false and defamatory, accusing her of a crime. She sought to hold Carlson and Fox News accountable for what she viewed as a baseless and damaging accusation.

Fox News’s legal defense, spearheaded by attorney Erin Murphy, hinged on a crucial and widely discussed argument: that Tucker Carlson Tonight is fundamentally a commentary and opinion program, not a traditional news broadcast, and therefore, a “reasonable viewer” would not interpret Carlson’s statements as factual assertions. Murphy contended that the show “markets itself… as opinion and spirited debate. That context matters.” The defense argued that Carlson’s “hyperbolic rhetoric” and “non-literal commentary” were protected under the First Amendment as expressions of opinion, which are generally afforded greater legal latitude than statements of fact in defamation cases.

In September 2020, U.S. District Judge Mary Kay Vyskocil sided with Fox News, dismissing McDougal’s lawsuit. In her ruling, Judge Vyskocil stated that “Given Mr. Carlson’s reputation, any reasonable viewer ‘arrives with an appropriate amount of skepticism’ about the statements he makes.” She further elaborated that Carlson’s remarks were “rhetorical hyperbole and opinion commentary intended to frame a political debate, and as such, are not actionable as defamation.” The judge noted that such “increasingly barbed” language is common in commentary talk shows and that the “general tenor” of the program should inform viewers that Carlson is not “stating actual facts.”

This ruling underscored the legal distinction between factual reporting and opinion/commentary in American media law. For a public figure like Karen McDougal to win a defamation suit, she would have had to prove “actual malice”—meaning Carlson knew his statements were false or acted with reckless disregard for the truth. The court found that McDougal’s arguments, which included claims of political bias and a personal relationship between Carlson and Trump, were speculative and did not meet the high bar required to establish actual malice. The outcome of this case, and the legal argument that “no reasonable viewer” should take Carlson’s statements as literal fact, became a significant point of contention and discussion regarding journalistic standards and the nature of truth in partisan media.

Moreover, news media have a responsibility to present stories in a way that addresses their inherent complexity. Many contemporary issues are multifaceted, requiring dedicated and often lengthy investigation to understand fully. In a media landscape where rapid reporting is the norm, audiences may find it tempting to gloss over the nuances for efficiency. Compounded by the sheer volume of information available, many news consumers seek concise, easy-to-digest stories. However, as the Committee of Concerned Journalists points out, media must strike a delicate balance between what readers want and what they need but might not immediately anticipate. Oversimplifying issues, whether for the sake of a quick story or to cater to public tastes, can be a profound violation of the vital information premise, leaving citizens ill-equipped to engage with critical societal challenges.

Presenting diverse perspectives is equally fundamental to journalism’s social responsibility. Media ethicist Jeremy Iggers highlights that because democracy thrives on the broadest possible participation of citizens in public life, diversity within journalism is paramount. This extends beyond merely featuring a variety of voices in stories; it also demands that newsroom staff themselves represent the diversity of genders, races, and backgrounds within society. According to the 2022 Newsroom Diversity Survey by the News Leaders Association (NLA) and the Medill School of Journalism, people of color constituted 21.9% of newsroom employees in U.S. print and online newsrooms. While an improvement from past decades, this figure still falls short of reflecting the nation’s demographic makeup. Journalists should actively seek to speak for all groups in society, “not just those with attractive demographics,” as the Committee for Concerned Journalists puts it. Ignoring or underrepresenting certain citizens in media coverage can be a subtle yet potent form of disenfranchisement, denying them a voice and visibility in the public discourse.

Finally, a critical function of the news media, deeply rooted in the intentions of the U.S. Constitution’s framers, is to monitor government and corporations. The press serves as a vital watchdog over those in positions of power (Committee of Concerned Journalists). This role ensures that businesses conduct their affairs transparently and that government actions remain accountable to the public. The Washington Post‘s investigation of the 1972 Watergate scandal remains the quintessential example of the media fulfilling this watchdog role. During Richard Nixon’s presidency, Post journalists uncovered information linking government agencies and officials to the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, part of an attempt to sabotage the Democratic campaign (Flanagan & Koenig, 2003). Their persistent coverage increased public awareness and ultimately pressured the government, leading to investigations and prosecutions (Baughman et al., 2001). In the modern era, this watchdog function has expanded to include scrutiny of mighty tech giants, social media platforms, and other influential entities that shape public life, ensuring they too operate with transparency and accountability.

Characteristics of Reliable Journalism

When discussing the characteristics of reliable journalism, the foundational principles remain consistent, even as the media landscape rapidly evolves. While CNN and other news networks faced scrutiny for their initial delay in reporting Michael Jackson’s death in 2009, many commended news organizations for prioritizing official confirmation. For many journalists and members of the public, ensuring accuracy, even when it means foregoing immediate breaking news, remains a hallmark of responsible journalism. This commitment to verification has only grown in importance in an age of rampant misinformation and disinformation.

Various unions and associations worldwide have produced hundreds of journalistic codes of ethics (White, 2008). While they may differ on specifics, these codes universally agree that the news media’s top obligation is to report the truth. When journalists refer to “truth,” they don’t mean it in an absolute, philosophical sense, but rather a practical truth: reporting facts as faithfully and accurately as possible. This notion encompasses an accurate representation of information from reliable, verifiable sources, and crucially, a comprehensive representation that presents multiple perspectives on an issue without suppressing vital information. The rise of “fake news” and partisan echo chambers has amplified the need for this commitment to verifiable facts and balanced context.

Along with an emphasis on truth, codes of ethics stress loyalty to citizens as a standard of primary importance. Especially in the current environment, where media outlets face increased financial pressure from declining traditional advertising revenues and the dominance of tech platforms, a persistent tension exists between responsible journalism and the demands for profit. Corporate and political influences continue to be a growing concern. However, journalists are reminded that while they have duties to other constituencies, “media products are not just economic.” Journalists must consistently prioritize the larger public interest above other interests, resisting pressures that could compromise their integrity or the public’s right to know (White).

Beyond the Textbook: Rethinking Infamous Media Ethics Cases

When discussing ethical breaches in journalism, the cases of Janet Cooke and Jayson Blair frequently emerge as textbook examples of plagiarism and fabrication. This prominence often raises a pertinent question: Are their cases truly the “worst” examples of journalistic misconduct, and why are they so consistently highlighted, particularly given that Black reporters constitute a relatively small proportion of the overall journalism industry?

Janet Cooke’s infamous 1980 Washington Post story, “Jimmy’s World,” a fabricated account of an 8-year-old heroin addict, led to a Pulitzer Prize that was later rescinded. Jayson Blair’s transgressions at The New York Times in 2003 involved both widespread fabrication and plagiarism, intensely shaking the credibility of one of the nation’s most esteemed newspapers. Both incidents caused immense public embarrassment for their respective news organizations and led to significant introspection within the industry about journalistic safeguards. Their cases were indeed high-profile and had profound consequences for public trust and the careers of those involved.

However, to suggest they are the only or even definitively the “worst” examples would overlook a broader history of ethical lapses by journalists of all backgrounds. The media landscape is, unfortunately, replete with instances of severe misconduct. Consider these other prominent cases:

- Stephen Glass: Fabricated numerous elaborate stories for The New Republic and other publications in the late 1990s, often inventing sources, quotes, and entire events. His downfall was dramatized in the film Shattered Glass.

- Patricia Smith: Fabricated sources and stories for The Boston Globe in the late 1990s, leading to her resignation.

- Jack Kelley: Fabricated stories, sources, and datelines for USA Today over several years in the early 2000s, leading to a major scandal and a lengthy internal investigation.

- Judith Miller: Her reporting for The New York Times on weapons of mass destruction in Iraq in the lead-up to the 2003 invasion faced significant criticism for questionable sourcing and accuracy, though it was not a case of outright fabrication or plagiarism.

- Mike Barnicle: Plagiarized material and fabricated elements in columns for The Boston Globe in the late 1990s.

- Clifford Irving: Faked an autobiography of Howard Hughes in the early 1970s, a sensational literary hoax.

- Sabrina Rubin Erdely: Faced severe criticism for inaccuracies and a lack of journalistic rigor in her 2014 Rolling Stone story “A Rape on Campus,” which was later largely retracted.

- Brian Williams: Fabricated or embellished stories about his experiences covering significant news events during his tenure as anchor for NBC News, leading to his suspension and reassignment in 2015.

While Cooke and Blair’s cases are undeniably significant due to the nature of their deceptions and the stature of the news organizations involved, the consistent emphasis on them as primary examples can inadvertently contribute to a skewed perception. Discussions on media ethics must present a comprehensive view of journalistic failures across the spectrum, ensuring that the lessons learned are not inadvertently tied to specific racial or demographic profiles, but rather to the universal principles of truth, accuracy, and accountability that underpin all credible journalism.

Good stories must also navigate the challenge of promising sensitivity toward, and protection of, those involved in the news. Responsible journalists strive to balance the disclosure of newsworthy information with respect for individual privacy. This balance can be challenging. On one hand, journalists should never expose private information solely for sensationalism or to cause harm. Issues like family life, sexual behavior, sexual orientation, or sensitive medical conditions generally remain in the realm of tabloids or unethical reporting, as their publication would violate the privacy of those involved without a clear public interest justification.

On the other hand, sometimes the media must publicize details about the private lives of individuals when it genuinely serves the common good. For example, in 2023, New York City Mayor Eric Adams faced intense scrutiny and ultimately an indictment on charges of bribery and campaign finance offenses. Media investigations, including those into his alleged acceptance of illegal campaign contributions and luxury travel, and his purported efforts to pressure city agencies on behalf of foreign nationals, brought to light details that, while personal, directly related to his conduct in public office and potential abuses of power. Although the publicity surrounding these matters caused the mayor and his associates significant harm, releasing information about the alleged incidents, particularly regarding the misuse of influence and potential corruption, served the best interests of the citizens by ensuring accountability in governance. The International Federation of Journalists offers three factors to serve as a rough guideline in determining whether a person’s privacy is in danger of being violated: the nature of the individual’s place in society, the individual’s reputation, and their place in public life. Politicians, judges, and others in elected office often must forgo their expectations of privacy for the sake of democracy and accountability—the public’s right to know if their elected officials engage in unethical or criminal conduct generally supersedes an individual’s right to privacy.

Because the press must serve the best interests of citizens in a democracy, journalists must act independently and strive for neutrality in their presentation of information. While the term “objectivity” has evolved and its absolute attainability is debated, the broader acceptance that reporting always occurs through a lens of personal experience, culture, beliefs, and background has grown (Myrick, 2002). Nevertheless, responsible journalism requires journalists to actively mitigate personal biases, avoid favoritism, and present news that offers a fair and complete picture of the issue or event. This means striving for balance, seeking diverse sources, and being transparent about limitations.

The principle of journalistic independence remains an essential component of the news media’s watchdog role. Journalists should rigorously avoid conflicts of interest—financial, political, or otherwise—that could compromise their reporting or create the appearance of bias. When such conflicts are unavoidable, ethical practice dictates that they be disclosed to the audience. A contemporary example of this concern is the ongoing discussion surrounding the financial stability of local news and potential government support. While some argue for public funding to preserve vital local journalism, many journalists and media ethicists express concern that direct government support could create a perceived or actual conflict of interest, potentially undermining the media’s critical watchdog role over government.

In addition to maintaining independence, the news media should foster an environment that allows for commentary and opposition. Providing platforms for citizens to voice concerns about journalistic conduct, offer alternative perspectives, or challenge narratives demonstrates transparency and helps to serve the public’s interest and maintain their trust. This open dialogue is crucial for accountability and for building a more informed and engaged citizenry.

The Effects of Bias in News Presentations

While the principles of ethical journalism require journalists to strive for neutrality in their reporting, a degree of inherent bias is almost inevitable due to the unique personal perspective, experiences, and cultural background that every journalist brings to their work. This reality has become increasingly apparent and a central point of public discussion in the modern media landscape.

What, exactly, does political bias in the media look like in contemporary practice? Modern studies and media analysis organizations offer insights beyond older academic findings. For example, organizations like AllSides and Ad Fontes Media use multi-partisan analyst teams and community feedback to rate news sources across a spectrum from left to right, and also assess their reliability. These analyses often reveal consistent patterns. One way bias manifests is through framing and emphasis, where news outlets with a particular ideological leaning may frame stories in a way that aligns with their perspective, emphasizing specific details while downplaying or omitting others. For instance, coverage of economic policy might focus on different impacts, such as corporate profits versus worker wages, depending on the outlet’s lean. Another form of bias appears in source selection, where outlets may consistently feature analysts, think tanks, or individuals who reinforce a particular viewpoint.

Furthermore, the language and tone employed can signal bias through the use of loaded language, emotionally charged words, or a consistently positive or negative tone towards specific political figures or parties. Finally, the decision of which stories to cover and how prominently to feature them—whether on the front page or buried deep, as a lead segment or a brief mention—can reflect an outlet’s political leanings. For example, during a significant political event, different networks might prioritize other aspects of the story based on their perceived audience or editorial stance.

The growing perception of media bias is well-documented. Pew Research Center studies consistently show a significant partisan divide in trust in news organizations. Republicans, in particular, are far more likely than Democrats to express distrust in national news outlets, often citing a belief that coverage unfairly favors one side or pushes a political agenda. This “trust gap” has widened over the past decade. A 2020 Pew study found that roughly eight-in-ten Americans (79%) believe news organizations tend to favor one side, with a vast majority of Republicans (91%) holding this view, compared to a still significant 69% of Democrats. Interestingly, Americans tend to blame the news organizations themselves for this perceived bias more than individual journalists, suggesting a belief that systemic issues or editorial directives are at play.

Of course, such biases in news media profoundly affect public opinion and contribute to political polarization. However, while the picture a journalist or particular news outlet creates may not entirely represent absolute objectivity, journalists with integrity are still ethically bound to strive for fairness and comprehensive coverage. This involves actively seeking out and presenting opposing views, citing sources transparently, and rigorously fact-checking.

In the modern era, the responsibility to navigate this complex information landscape also falls heavily on the general public. Good media consumers must employ critical analysis skills rather than passively receiving information. This includes cross-referencing stories from multiple sources with different perceived biases (tools like AllSides and Ad Fontes Media can assist with this), scrutinizing headlines for sensationalism or loaded language, evaluating the credibility of sources, and being aware of their own confirmation biases. Readers and viewers now have unprecedented resources to research an issue further and draw their informed conclusions. Understanding the ethical obligations of those who work in the mass media and the potential consequences of failing to uphold them is crucial for maintaining a well-informed citizenry in an increasingly fragmented and opinion-driven media environment.

The Ethics of Digital Photo Manipulation

The pervasive nature of digital technology has introduced complex ethical dilemmas into the realm of photojournalism and visual communication, particularly concerning the manipulation of images. While photo editing has existed since the dawn of photography, digital tools offer unprecedented ease and subtlety in altering images, blurring the line between enhancement and deception. The core ethical question revolves around how much manipulation is acceptable before an image ceases to be a truthful representation of reality and begins to mislead the audience. This concern is particularly acute in news and documentary photography, where the expectation of factual accuracy is paramount. Extensive manipulation, such as adding or removing elements, altering colors to change mood dramatically, or compositing different images, can fundamentally distort the truth, erode public trust in media, and even modify historical records. The integrity of an image is tied to its ability to convey an honest depiction of events.

A classic early example of photo manipulation, though pre-digital, that sets the stage for debates on image integrity is Stalin and the “Vanishing Commissar” (early to mid-20th century). Joseph Stalin’s regime famously used photo manipulation to erase political rivals from official photographs after they fell out of favor or were executed. One prominent instance involved Nikolai Yezhov, a powerful NKVD chief, who was prominently featured with Stalin in many photographs. After Yezhov’s execution in 1940, he was meticulously removed from official images, making it appear as if he had never been there. This extensive and systematic manipulation wasn’t just about aesthetic improvement; it was a deliberate act of historical revisionism and control, demonstrating how altering images could fundamentally reshape public perception and historical memory. This case underscores the profound ethical implications when visual truth is sacrificed for a political agenda.

Another significant case, illustrating the subtle dangers of manipulation, is the National Geographic Pyramids Cover (1982). For its February 1982 cover, National Geographic published a famous photograph of the Pyramids of Giza. However, to fit the vertical format of the cover, the two pyramids were digitally (using darkroom techniques of the time) moved closer together than they are in reality. While the magazine argued it was merely a stylistic adjustment for layout purposes, the incident sparked a significant ethical debate within photojournalism. Critics argued that even such a seemingly minor alteration compromised the authenticity of the documentary photograph and set a dangerous precedent for manipulating reality. This case helped define a stricter ethical boundary for photojournalists, emphasizing that even subtle changes for aesthetic reasons can undermine the credibility of the image as a factual record.

More recently, the L.A. Riots “Burning Bus” Composite (1992) provides a powerful example of how combining elements from different moments can create a misleading narrative. During the Los Angeles riots, TIME magazine faced scrutiny for its cover image. While their main competitor, Newsweek, featured a relatively unmanipulated photograph of a man standing in front of a burning building, TIME‘s cover showed a composite image created by combining two different pictures: a burning bus and a separate photo of a man. Although both elements were fundamental, combining them in a way that differed from reality was criticized for sensationalizing the event and manipulating the public’s perception of the riots’ intensity. This highlights the ethical challenge of compositing, where elements individually true can collectively convey a distorted overall truth, raising questions about journalistic responsibility in visual storytelling.

The Ethics of Sensationalism

The pervasive use of sensationalism in media, characterized by its focus on exciting, shocking, or dramatic content to attract attention, has become a significant ethical concern. While sensationalism has always been a tool in media, its rise in usage can be attributed to several interconnected factors. Primarily, it’s driven by economic pressures and intense competition within the media landscape. In a fragmented media environment with countless news outlets, websites, and social media feeds vying for eyeballs and clicks, sensational headlines and dramatic narratives are often seen as the most effective way to cut through the noise and attract a mass audience. Increased viewership or readership translates directly into higher advertising revenues or subscription numbers. Additionally, the 24/7 news cycle and the demand for constant, immediate content exacerbate this trend; in the rush to be first, nuanced reporting can be sacrificed for quick, attention-grabbing stories. The rise of social media also plays a crucial role, as sensational content is often highly shareable, generating viral spread and further amplifying its reach, even if its factual basis is thin.

Historically, the use of sensationalism has deep roots in the media. The era of Yellow Journalism, particularly in the 1890s, stands out as perhaps the most notorious historical example of rampant sensationalism. Characterized by exaggerated headlines, fabricated stories, scare tactics, and often lurid illustrations, yellow journalism was epitomized by the circulation battle between William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. These newspapers famously sensationalized events leading up to the Spanish-American War, with headlines like “Remember the Maine!” inciting public fervor. The ethical failure here was the deliberate distortion of truth and the use of emotional manipulation to sell newspapers, often at the expense of accurate reporting and thoughtful public discourse. This period highlights how intense competition can drive media outlets to abandon ethical standards in pursuit of profit and influence.

The rise of tabloid journalism and paparazzi culture from the mid- to late 20th century marked another significant wave of sensationalism. These outlets specialized in celebrity gossip, crime, scandals, and the bizarre, often employing aggressive paparazzi tactics to capture invasive images and unverified stories. The ethical concerns revolved around invasion of privacy, potential harassment, and the blurring of lines between public interest and prurient curiosity. The tragic death of Princess Diana in 1997, heavily linked to the aggressive pursuit by paparazzi, brought global attention to the severe consequences of this form of sensationalism and sparked intense debates about media responsibility and privacy.

Finally, the advent of cable news and “infotainment” from the late 20th to early 21st century further entrenched sensationalism. With the proliferation of 24-hour news channels, the continuous need to fill airtime led to increased reliance on dramatic visuals, emotionally charged interviews, and speculative commentary. Events like celebrity trials, such as the O.J. Simpson trial, received extensive, often sensationalized, wall-to-wall coverage, turning serious legal proceedings into public spectacles. The drive for ratings meant that “breaking news” banners became ubiquitous, even for minor developments, and expert panels often engaged in heated debates designed more for entertainment than enlightenment. This trend continues with modern cable news, where outrage and emotional appeals usually take precedence over in-depth, nuanced analysis, contributing to the public’s perception of bias and a lack of objectivity in news reporting.

Beyond the Byline: The Ethical Pillars of Journalism

The Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) Code of Ethics serves as a cornerstone for ethical conduct in American journalism, providing a comprehensive framework that guides reporters, editors, and news organizations in their pursuit and dissemination of information. It is not a set of enforceable laws but rather a statement of principles and standards that journalists should aspire to uphold, aiming to foster public trust and ensure responsible reporting. The Code is built upon four foundational pillars: Seek Truth and Report It, Minimize Harm, Act Independently, and Be Accountable and Transparent.

The first and arguably most paramount principle, Seek Truth and Report It, underscores the journalist’s primary responsibility to the public. This goes beyond merely relaying facts; it demands accuracy, fairness, and thoroughness. Journalists are urged to be honest and courageous in gathering, reporting, and interpreting information, to test the accuracy of statements made by all sources, and to identify sources whenever feasible. It also calls for providing context, avoiding stereotypes, and distinguishing between news, opinion, and advertising. In practice, this means a reporter investigating a public official’s alleged corruption must diligently verify every claim, interview multiple sources, and present all sides of the story fairly, even if it complicates the narrative.

Secondly, Minimize Harm emphasizes the ethical imperative to treat sources, subjects, and colleagues with respect and compassion. While the pursuit of truth is vital, it should not come at the cost of unnecessary suffering. This principle encourages journalists to be sensitive when reporting on private lives, vulnerable individuals, or tragic events, and to recognize that gathering and reporting information may cause harm or discomfort. It prompts questions like: Is the public’s need to know truly paramount over an individual’s right to privacy in this instance? For example, when covering a natural disaster, a journalist must balance the need to convey the devastation with the ethical responsibility to avoid exploiting victims’ grief or invading their personal space unnecessarily.

The third pillar, Act Independently, stresses the importance of avoiding conflicts of interest, real or perceived. Journalists should remain free of associations and activities that may compromise their integrity or credibility. This means refusing gifts, favors, fees, or special treatment, and declining secondary employment or political involvement that could create a conflict. News organizations are encouraged to resist pressure from advertisers, special interest groups, or influential individuals. A sports reporter, for instance, should not accept free travel or merchandise from a team they cover, ensuring their reporting remains unbiased and free from external influence. This principle is crucial for maintaining public trust in the media’s objectivity.

Finally, Be Accountable and Transparent calls for journalists to take responsibility for their work and to be open about their processes. This includes admitting mistakes and correcting them promptly, explaining ethical choices and methods to the public, and inviting public dialogue about journalistic conduct. It also encourages news organizations to expose unethical practices in journalism and to abide by the same high standards they expect of others. Suppose a newspaper publishes an inaccurate detail in a story. In that case, the Code dictates that a correction should be issued clearly and promptly, demonstrating a commitment to accuracy and transparency to the audience.

The SPJ Code of Ethics is not a static document; it is periodically reviewed and updated to address new challenges posed by evolving technologies and media landscapes, such as the rise of social media, citizen journalism, and artificial intelligence. Its application in journalism is a continuous process of ethical reasoning, requiring journalists to weigh competing values and make difficult decisions under pressure, all with the ultimate goal of serving the public interest responsibly. While perfect adherence may be elusive, the Code provides an essential moral compass for the profession. The Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) Code of Ethics serves as a cornerstone for ethical conduct in American journalism, providing a comprehensive framework that guides reporters, editors, and news organizations in their pursuit and dissemination of information. It is not a set of enforceable laws but rather a statement of principles and standards that journalists should aspire to uphold, aiming to foster public trust and ensure responsible reporting. The Code is built upon four foundational pillars: Seek Truth and Report It, Minimize Harm, Act Independently, and Be Accountable and Transparent.

The first and arguably most paramount principle, Seek Truth and Report It, underscores the journalist’s primary responsibility to the public. This goes beyond merely relaying facts; it demands accuracy, fairness, and thoroughness. Journalists are urged to be honest and courageous in gathering, reporting, and interpreting information, to test the accuracy of statements made by all sources, and to identify sources whenever feasible. It also calls for providing context, avoiding stereotypes, and distinguishing between news, opinion, and advertising. In practice, this means a reporter investigating a public official’s alleged corruption must diligently verify every claim, interview multiple sources, and present all sides of the story fairly, even if it complicates the narrative.

Secondly, Minimize Harm emphasizes the ethical imperative to treat sources, subjects, and colleagues with respect and compassion. While the pursuit of truth is vital, it should not come at the cost of unnecessary suffering. This principle encourages journalists to be sensitive when reporting on private lives, vulnerable individuals, or tragic events, and to recognize that gathering and reporting information may cause harm or discomfort. It prompts questions like: Is the public’s need to know truly paramount over an individual’s right to privacy in this instance? For example, when covering a natural disaster, a journalist must balance the need to convey the devastation with the ethical responsibility to avoid exploiting victims’ grief or invading their personal space unnecessarily.

The third pillar, Act Independently, stresses the importance of avoiding conflicts of interest, real or perceived. Journalists should remain free of associations and activities that may compromise their integrity or credibility. This means refusing gifts, favors, fees, or special treatment, and declining secondary employment or political involvement that could create a conflict. News organizations are encouraged to resist pressure from advertisers, special interest groups, or influential individuals. A sports reporter, for instance, should not accept free travel or merchandise from a team they cover, ensuring their reporting remains unbiased and free from external influence. This principle is crucial for maintaining public trust in the media’s objectivity.

Finally, Be Accountable and Transparent calls for journalists to take responsibility for their work and to be open about their processes. This includes admitting mistakes and correcting them promptly, explaining ethical choices and methods to the public, and inviting public dialogue about journalistic conduct. It also encourages news organizations to expose unethical practices in journalism and to abide by the same high standards they expect of others. Suppose a newspaper publishes an inaccurate detail in a story. In that case, the Code dictates that a correction should be issued clearly and promptly, demonstrating a commitment to accuracy and transparency to the audience.

The SPJ Code of Ethics is not a static document; it is periodically reviewed and updated to address new challenges posed by evolving technologies and media landscapes, such as the rise of social media, citizen journalism, and artificial intelligence. Its application in journalism is a continuous process of ethical reasoning, requiring journalists to weigh competing values and make difficult decisions under pressure, all with the ultimate goal of serving the public interest responsibly. While perfect adherence may be elusive, the Code provides an essential moral compass for the profession.