14.4 Ethical Considerations of the Online World

Online media is undergoing rapid evolution, with technology advancing at a pace that often outpaces the ability of legislation and policy to keep up. This dynamic environment has brought to the forefront issues such as individuals’ rights to privacy, copyright protections, and fair use restrictions. These issues have become the subject of numerous court cases and public debates, as lawmakers, judges, and civil liberties organizations grapple with the ever-changing landscape of technology and the access it provides to previously restricted information. This section will delve into some of the most pressing issues in today’s online media environment, inviting you to reflect on the ethical challenges in mass media and how they manifest in the areas of personal privacy, copyright law, and plagiarism. What impact will this fast-paced media environment have?

Privacy and Surveillance

Concerns surrounding online privacy have intensified dramatically in recent years, prompting a fundamental re-examination of whether the pervasive collection of personal information on websites infringes upon individuals’ constitutional rights. While the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly guarantee a general right to privacy, the Bill of Rights establishes protections for the privacy of beliefs, the sanctity of the home, and the security of persons and possessions from unreasonable searches. Moreover, courts have consistently interpreted the “right to liberty” clause as implicitly guaranteeing an individual’s right to personal privacy in various contexts (Linder, 2010). These foundational constitutional principles face complex challenges in the digital age when considering the storage of a person’s credit card data online, the tracking of their internet searches, or the use of cookies to collect information about their purchasing habits. Given the rapid evolution of online media, federal legislation has struggled to keep pace, leading to numerous and ongoing courtroom battles. A notable modern example involves President Donald Trump’s protracted legal disputes with platforms like Twitter (now X) over issues ranging from account suspensions to government requests for user data. These cases highlight the intricate legal questions surrounding platform content moderation, government access to private communications, and the application of constitutional protections to digital interactions. Often, platforms assert user privacy rights against government demands, while governments argue for access in matters of national security or public safety.

In defense of information collection, many online services argue that by using their platforms, individuals implicitly agree to make their personal information available. However, a significant portion of the public remains either unaware of the full extent of pervasive surveillance capabilities or lacks the technical knowledge to protect their data when utilizing online tools adequately. As an increasing number of people turn to the internet for commerce, communication, social networking, and media consumption, their digital footprints expand exponentially, with data continually stored online. Every action, from subscribing to a streaming service or an online magazine, joining a digital organization, donating to a charity, contributing to a political campaign, or simply searching the pages of a government website, generates data that is meticulously recorded and stored (Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, 2010). For instance, cookies—small text files that web servers embed in users’ hard drives—remain a fundamental tool that helps search engines like Google and e-commerce giants like Amazon track customers’ search histories, buying habits, and browsing patterns. While these technologies aim to customize users’ experiences and deliver personalized third-party advertisements based on demographics and behavior, privacy advocates contend that such practices foster overly intrusive, if not predatory, advertising (Spring, 2010). Moreover, given the immense volume of daily requests search engines receive for specific user information, often tied to criminal investigations and civil lawsuits, critics harbor concerns that the pervasive data collection could lead to unfair or even erroneous profiling of individuals, contributing to a broader perception of algorithmic bias in how information is presented and targeted.

Much of this extensive information is collected and stored without users’ explicit knowledge or fully informed consent, even though terms of service agreements for most software typically disclose data collection practices. However, few individuals possess the patience or dedicated time to meticulously read and fully comprehend the dense, legalistic language of these lengthy agreements. Even when users do invest the effort to understand the terms, they are often faced with a crucial, all-or-nothing decision: agree to the terms and forfeit specific privacy controls, or forgo the use of the software or service entirely. This “consent fatigue” is a growing concern in the digital age.

Internet users genuinely concerned about their online privacy must also contend with the increasingly sophisticated practice of combining online data with offline information, creating an even more comprehensive and intimate profile of individuals. Data providers, commonly known as data brokers, such as Acxiom, Experian, and Epsilon, continuously pool vast quantities of both online behavioral data and offline demographics—including public records, purchase histories, and survey responses—to develop intricate “digital dossiers” for online advertisers seeking to reach particular target audiences. This seamless integration of online and offline information provides a nearly complete picture of someone’s life. Suppose advertisers seek a 56-year-old retired and divorced female educator who owns a home and a dog, suffers from arthritis, and enjoys playing tennis at a local fitness club. In that case, they can now identify her with remarkable precision. While this comprehensive online profiling is highly beneficial for granular targeted advertising, it also starkly underscores the unprecedented extent of our collective digital footprint and the challenges of meaningful de-identification of data. Although advertisers often assert that they identify individuals by broad demographic subgroups rather than by name, privacy advocacy organizations, such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, continue to champion the necessity of stronger legal protections, greater transparency regarding data collection practices, and more robust mechanisms for user control over personal information (Spring, 2010).

Users also willingly provide a vast amount of personal information about themselves through online social networks, including their names, contact details, photographs, personal interests, and location data. This self-disclosed information, combined with data inferred from online activity, is increasingly leveraged in ways that extend beyond social interaction. Creditors now frequently examine individuals’ social media profiles to assess their likelihood of maintaining good credit, and banks may access this information to inform loan decisions (Mies, 2010). Furthermore, if users do not meticulously monitor and adjust their privacy settings on social media platforms, publicly shared photographs, personal details, and other seemingly private information can be easily accessed by anyone performing a simple internet search, posing significant risks to personal security and autonomy.

The scope of surveillance in the digital realm ranges from the monitoring of online activity by employers and other private institutions, ensuring adherence to platform guidelines or company policies, to high-level government investigations of national security threats. The USA PATRIOT Act, enacted just weeks after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, significantly expanded the federal government’s authority to access citizens’ personal information. Under this legislation, and subsequently through provisions of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), particularly Section 702, authorities can compel Internet service providers and other third parties to provide access to personal records. Government officials may access an individual’s email communications, web searches, and other digital data if they suspect the person of engaging in or having connections to terrorist or foreign intelligence activities (American Civil Liberties Union, 2003; Olsen, 2001). Civil liberties organizations have consistently voiced deep concerns that these expansive powers could serve as a backdoor for the government to conduct undisclosed surveillance that does not solely involve the direct threat of terrorism. For example, under specific interpretations, the government could conduct wiretaps of internet communications where a criminal investigation is a primary objective, as long as intelligence gathering is also deemed a significant purpose of the inquiry (Harvard Law School). The ongoing tension between national security imperatives and the protection of individual privacy rights remains a central and evolving challenge in contemporary digital policy and law.

Fair Use and Plagiarism

The pervasive accessibility of information online has significantly amplified concerns surrounding plagiarism and copyright infringement, as the ease of copying and pasting content across platforms can blur ethical and legal boundaries. While these two concepts are often confused, it is crucial to distinguish between them. This section will provide an overview of copyright law, its issues and limitations, and its relationship to, and distinction from, plagiarism.

Copyright Infringement

Copyright offers a form of protection provided by U.S. law, which automatically bestows upon the creator of an original artistic or intellectual work certain rights, including the right to distribute, copy, and modify the work (U.S. Copyright Office). For example, if Marcus rents a movie from Netflix and watches it with his friends, he hasn’t violated any copyright laws because Netflix has obtained a license to lend the film to its customers. However, he rents a physical version of the movie and burns a copy to watch later; he has violated copyright law because he has neither paid for nor obtained the film creators’ permission to copy the movie. Copyright law applies to most books, songs, movies, art, essays, and other pieces of creative work. However, after a certain length of time (ranging from 70 to 120 years, depending on the publication circumstances), innovative and intellectual works enter the public domain, allowing any entity to use or copy the content freely.

Digital Tomes, Legal Thorns: The Google Books Saga

In 2002, Google embarked on an ambitious project to digitize millions of books from academic libraries, aiming to make them broadly accessible online. Since its inception, Google has scanned and made searchable over 40 million books through Google Books. Of these, a significant portion resides in the public domain, allowing users to browse and download them in “full view” for free. Books still under copyright are typically presented as limited previews, offering users access to a portion of the text. Google has consistently framed this initiative as a monumental step toward the democratization of knowledge, asserting that it provides unprecedented access to texts for readers who would otherwise be unable to obtain them. However, this expansive project has long been met with strong opposition from many authors, publishers, and legal authorities who argue that it constitutes a massive copyright violation. This contention led to significant legal battles, most notably the class-action lawsuits filed against Google by the Authors Guild and the Association of American Publishers in 2005 (Newitz, 2010).

The legal complexities surrounding Google Books culminated in a proposed settlement agreement, initially reached in 2008 and later revised. This settlement, which the courts ultimately rejected, was described by some legal experts, including William Cavanaugh of the U.S. Department of Justice, as fundamentally “turning copyright law on its head.” The proposed terms of the agreement stipulated that in exchange for a substantial sum, part of which would compensate authors and publishers, Google would be released from liability for copying the books. Crucially, it would have granted Google the right to charge money for individual and institutional subscriptions to its Google Books service, providing subscribers with full access to the digitized books, even those still under copyright. While authors were given an option to “opt out” of the agreement, requesting their books be removed from Google’s servers, the existence of separate deals between Google and numerous publishers complicated this process, potentially overriding individual authors’ rights to opt out (Oder, 2010).

The rejection of the settlement in 2011 by a U.S. federal judge, who ruled that it was “not fair, adequate, and reasonable,” marked a pivotal moment. The court expressed concerns that the settlement would have granted Google a de facto monopoly over orphan works (copyrighted books whose rights holders cannot be identified or located) and would have significantly altered copyright law through a private agreement rather than legislative action. Despite this setback, Google Books continues to operate, adhering more strictly to fair use principles for in-copyright works, primarily offering snippets and limited previews. At the same time, full access remains for public domain titles. The ongoing legal and ethical debates surrounding large-scale digitization projects like Google Books reflect a broader tension between the public good of knowledge dissemination and the protection of intellectual property rights in the digital age. This case has become a landmark example in the evolving discourse on copyright in the internet era, influencing discussions on digital libraries, fair use, and the role of technology companies in shaping access to cultural heritage.

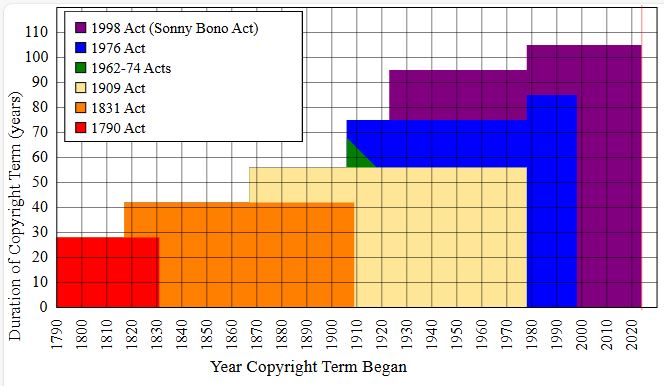

Some works are intentionally placed in the public domain by their creators, who choose to make them available to anyone without requiring permission, often through licenses like Creative Commons Zero (CC0). However, the majority of works enter the public domain because their copyright term has expired. In the United States, anything published before January 1, 1929, is generally considered to be in the public domain. Additionally, various changes to U.S. copyright law over the years have led to some works entering the public domain earlier or later, depending on their publication date and whether specific registration or renewal requirements were met under older laws. For instance, before 1978, works generally had an initial copyright term that required renewal to extend protection; failure to renew meant the work entered the public domain. The evolution of U.S. copyright law since its inception in 1790 has been marked by significant shifts, often extending protection periods.

While copyright law provides robust protections for creators, it also incorporates crucial limitations, most notably the doctrine of “fair use.” This policy stipulates that the public may freely use copyrighted material for specific transformative purposes, such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, research, or parody, without needing permission from the copyright holder (U.S. Copyright Office, 2009). For example, when a film critic writes a review for an online publication, according to fair use, they can summarize the plot, quote dialogue, or include short clips from the film, regardless of whether the filmmakers explicitly agreed to this use. When determining whether a particular use constitutes fair use, U.S. courts typically consider four factors:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is commercial or is for nonprofit educational purposes.

- The nature of the copyrighted work.

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used of the copyrighted work as a whole.

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work (U.S. Copyright Office, 2009).

The distinction between fair use and copyright infringement is not always immediately apparent, often requiring nuanced legal interpretation. For one thing, courts have deliberately avoided issuing rigid guidelines that specify exact quantities—such as a specific number of words, lines of code, or musical notes—that people can use without permission. This ambiguity means that fair use determinations are highly fact-specific and often depend on the context and transformative nature of the new work.

| Fair Use | Not Fair Use |

| Wright v. Warner Books Inc. (1991)

The court considered whether a biographer’s use of excerpts from Richard Wright’s unpublished letters and journal entries in a biography constituted fair use. Considerations: The court ruled the copied material amounted to less than one percent of Wright’s total letter material, and the biographer’s purpose was to inform and provide critical commentary on Wright’s life, which was considered a transformative use for scholarly and biographical purposes, weighing in favor of fair use despite the unpublished nature of the works. |

Castle Rock Entertainment Inc. v. Carol Publishing Group (1998)

Carol Publishing Group published a book of trivia questions about the TV series Seinfeld, including direct quotes and questions based on characters and events from the show. Considerations: The court determined this was not fair use because the trivia book was largely derivative and directly competed with, or infringed upon, Castle Rock Entertainment’s (the copyright holder’s) ability to create its authorized trivia books or other derivative works from the series, as the purpose of the trivia book was primarily commercial and non-transformative, merely repackaging the original content. |

| Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. (1994)

The rap group 2 Live Crew created a parody of Roy Orbison’s song “Oh, Pretty Woman.” Considerations: The Supreme Court ruled that 2 Live Crew’s commercial parody could be fair use, emphasizing the transformative nature of parody, which critiques or comments on the original work; although commercial and taking a recognizable portion, its parodic purpose weighed heavily in favor of fair use, requiring only enough of the original to “conjure up” the object of its satire. |

Los Angeles News Service v. KCAL-TV Channel 9 (1997)

A TV news station used a 30-second segment of a four-minute video that depicted the beating of a Los Angeles man, with the copyright owned by the Los Angeles News Service. Considerations: The court found the news station’s use was not fair use because the 30-second segment constituted a significant portion of the total video, both quantitatively and qualitatively, and KCAL-TV profited directly from its use of the footage in its news broadcast, thereby infringing on the Los Angeles News Service’s ability to license and market the video itself. |

| Cariou v. Prince (2013)

Artist Richard Prince created new artworks by significantly altering and incorporating photographs taken by Patrick Cariou, which depicted Rastafarians in Jamaica. Considerations: The Second Circuit Court of Appeals found many of Prince’s works to be fair use because they were transformative, conveying a new message or aesthetic, as Prince’s alterations, such as painting over the images or combining them with other elements, changed the original photographs’ context and meaning, making them distinct from Cariou’s original documentary purpose. |

Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc. (1997)

A book titled “The Cat NOT in the Hat! A Parody by Dr. Juice” was published, which mimicked Dr. Seuss’s style and characters to comment on the O.J. Simpson murder trial. Considerations: The court ruled this was not fair use, primarily because it was not a true parody of Dr. Seuss’s work itself. Instead, it used the recognizable style and characters to comment on an external event, finding it lacked sufficient transformative quality and could potentially harm the market for authorized derivative works, as it too closely resembled the original without offering genuine critical commentary on the original work. |

| Authors Guild v. Google (2015)

Google scanned millions of copyrighted books to create a searchable database, displaying snippets of text and providing links to where books could be purchased. Considerations: The Second Circuit and subsequently the Supreme Court (by denying certiorari) affirmed that Google’s mass digitization project constituted fair use, finding the use highly transformative, creating a new research tool that allowed users to search for information across a vast collection of books. The display of snippets was limited and did not serve as a substitute for the original books, thus not significantly harming the market. |

Associated Press v. Fairey (2011 settlement)

Artist Shepard Fairey created his iconic “Hope” poster of Barack Obama using an Associated Press photograph as a source image without permission. Considerations: Though settled out of court, the legal arguments illustrate why it was likely not fair use: Fairey’s use was commercial, and although he altered the image, the AP argued it was not sufficiently transformative to qualify as fair use, as it still directly exploited the recognizable core of their copyrighted photograph for a new commercial purpose without proper licensing, impacting the market for licensing the original picture. |

| Lenz v. Universal Music Corp. (2015)

Stephanie Lenz uploaded a 29-second home video of her toddler dancing to Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy,” prompting Universal Music to issue a takedown notice. Considerations: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that copyright holders must consider fair use before sending a DMCA takedown notice, establishing that a reasonable, good-faith consideration of fair use is required by rights holders, acknowledging that short, non-commercial uses, even of popular music, can fall under fair use. |

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (2023)

The Andy Warhol Foundation licensed one of Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series” silkscreen prints, which was based on a copyrighted photograph of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith, for use on a magazine cover. Considerations: The Supreme Court ruled that the Foundation’s commercial licensing of Warhol’s Prince image for a magazine cover was not fair use, finding that while acknowledging Warhol’s original artistic transformation of Goldsmith’s photograph, the Court focused on the “purpose and character” of the secondary use (the commercial licensing), determining it was not sufficiently transformative from Goldsmith’s original commercial licensing purpose to qualify as fair use, emphasizing that the commercial nature of the use weighed heavily against fair use when the new work served substantially the same commercial purpose as the original. |

The Creative Commons

The evolution of digital content creation and sharing has led to innovative approaches to intellectual property, notably with Creative Commons (CC) licenses and Open Educational Resources (OER). Both concepts emerged as a response to the traditional “all rights reserved” copyright system, which often felt restrictive in the age of easy digital replication and sharing.

Creative Commons was founded in 2001 by legal scholars, artists, and activists seeking a middle ground between traditional copyright’s stringent restrictions and the public domain’s complete lack of rights. The organization developed a suite of standardized, free-to-use licenses that allow creators to specify how others can use their work, giving them more flexibility than standard copyright. These licenses are built upon existing copyright law but offer a spectrum of “some rights reserved” options. For example, a CC BY license permits others to use, distribute, and build upon a work, even commercially, as long as they provide attribution to the original creator. Other licenses might add conditions like “NonCommercial” (NC), meaning it cannot be used for profit, or “ShareAlike” (SA), requiring any derivative works to be licensed under the same terms. The use of Creative Commons has exploded, with billions of works across the internet, from photos on Flickr to articles on Wikipedia, utilizing these licenses to facilitate broader access and reuse.

Parallel to the rise of Creative Commons, the concept of Open Educational Resources (OER) gained significant traction. OER refers to teaching, learning, and research materials that are either in the public domain or released under an open license (like many Creative Commons licenses) that permits free and perpetual permission for everyone to engage in what are known as the “5 Rs”: Retain (make, own, and control copies of the content), Reuse (use the content in a wide range of ways), Revise (adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content), Remix (combine original or revised content with other open material), and Redistribute (share copies of the content). The OER movement aims to make education more accessible and affordable by reducing the cost of textbooks and learning materials, thereby removing significant barriers to learning. A landmark moment for OER was the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) OpenCourseWare initiative in 2002, which made virtually all of MIT’s course content freely available online, demonstrating the vast potential of open education.

Project Gutenberg (for classic e-books in the public domain), Wikibooks, and specialized repositories for specific disciplines collectively demonstrate the vibrant ecosystem of open content. They embody the spirit of sharing and collaboration fostered by Creative Commons, ultimately working to democratize access to knowledge and educational opportunities globally.

Plagiarism

Sometimes plagiarism becomes confused with copyright violation. However, the two words do not mean the same thing. At the same time, some overlap exists between the concepts; not every instance of plagiarism involves a copyright violation, and not every instance of copyright violation constitutes an act of plagiarism. For one thing, while copyright violation can involve a wide range of acts, plagiarists more narrowly use someone else’s information, writing, or speech without properly documenting or citing the source. In other words, plagiarism involves representing another person’s work—or content generated by an entity like an artificial intelligence—as one’s own.

As the U.S. Copyright Office points out, it is possible to cite a copyrighted source of information without obtaining permission to reproduce that information. In such a case, the user has violated copyright law even though they have not plagiarized the material. Similarly, a student writing a paper could copy sections of a document in the public domain or incorporate text generated by an AI tool without properly citing their sources. In the former instance, they would not have broken any copyright laws (as public domain works are free to use), but representing the information as their work would qualify as plagiarism. In the latter, the ethical and legal lines are still being drawn, but presenting AI-generated content as one’s original thought without disclosure is widely considered academic plagiarism.

Plagiarism, a perennially serious problem at academic institutions, has recently become even more prevalent and complex due to the digital age and the advent of sophisticated Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools. The ease of copying and pasting online content into a word-processing document can make it highly tempting for students to plagiarize material for research projects and critical papers. AI tools have significantly amplified this temptation, with huge language models (LLMs) capable of generating human-like text, which offer a new and readily available “shortcut” for producing written assignments. Additionally, numerous online “essay mills” or “assignment help” services continue to offer students the ability to download or purchase pre-written documents, now often incorporating AI-generated content. Regardless of how students engage in plagiarism, the underlying problem persists, with academic integrity organizations and university policies continually adapting to address these challenges.

To combat the rise in plagiarism, including that facilitated by AI, many schools and universities now subscribe to sophisticated services that allow instructors to check students’ work for unoriginal material. Turnitin, for instance, is a widely used analytics tool that compares student writing against a vast database that includes work from online publications, academic databases, documents available through major search engines, and other student papers previously submitted to the service. These services are rapidly evolving to incorporate AI-detection capabilities, though the effectiveness and reliability of such tools are still subjects of ongoing development and debate.

Many researchers link the problem to the fact that students don’t fully understand what constitutes plagiarism, especially in the context of digital and AI-generated content. Some students, for instance, mistakenly treat information they find online as if its mere online presence signified an automatic placement within the public domain (Auer & Krupar, 2001). Similarly, there’s a growing misunderstanding regarding AI-generated text: some believe that because they prompted the AI, the output is inherently their original work, overlooking the fact that the AI’s “knowledge” is derived from vast amounts of existing data, some of which may be copyrighted or require attribution. This misunderstanding highlights a critical need for ongoing education on academic integrity, proper source attribution, and ethical engagement with AI tools. The following list provides suggestions for avoiding plagiarism in original work:

- Don’t procrastinate.

- Avoid taking shortcuts.

- Take thorough notes and keep accurate records.

- Rephrase ideas originally.

- Provide citations or attributions for all sources.

- Ask the instructor when in doubt.

While plagiarism remains a significant academic concern, it also occurs frequently in professional print and digital media. Writers, whether through carelessness, laziness, or intentional deception, may lift content from existing materials without properly citing or reinterpreting them. This extends to the professional use of AI; if content generated by an AI is presented as entirely original human work without disclosure, or if it inadvertently reproduces copyrighted material from its training data, it can lead to accusations of plagiarism or even copyright infringement. In an academic setting, plagiarism can lead to severe consequences, including failure, suspension, or even expulsion from an institution. However, outside of academia, the consequences may prove even more damaging. Writers, journalists, and public figures have lost publishing contracts, permanently damaged their reputations, and even ruined their careers over instances of plagiarism. A notable example from the music industry is the case of Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd. (1976), where the court determined that George Harrison had “subconsciously” plagiarized the musical essence of Ronald Mack’s song “He’s So Fine” for his composition “My Sweet Lord,” leading to a finding of copyright infringement. Hbomberguy accused several prominent YouTube content creators of plagiarism, sparking a notable controversy within the online commentary community regarding proper attribution and content originality. This incident highlighted ongoing debates about journalistic integrity and ethical content creation on digital platforms. More recently, in the literary world, authors have faced public backlash and career repercussions for instances of alleged plagiarism, sometimes involving close similarities in plot points, character arcs, or specific phrasing, raising questions about the role of AI in their creative process.

The integration of AI into content creation necessitates a re-evaluation of educational practices, emphasizing the process of learning, critical thinking, and the development of unique intellectual contributions, rather than just the final product. The focus is shifting towards fostering responsible and ethical engagement with AI tools, where users understand the origins of information, whether human-authored or AI-generated, and properly attribute or transform it. This new frontier in plagiarism and authorship challenges us to redefine originality and integrity in an increasingly automated world.

This chapter attempted to outline some of the key issues in media ethics, particularly as they relate to privacy rights, plagiarism, and copyright laws, acknowledging the profound impact of digital and AI technologies on these enduring challenges.