15.2 Government Regulation of Media

The U.S. federal government has long been involved in the regulation of media, a relationship that has continuously evolved alongside technological advancements and societal shifts. Since the early 1900s, media in all its forms have operated under governmental jurisdiction, with regulatory efforts transforming as new communication technologies have emerged and expanded their reach to larger, more diverse audiences. This oversight aims to balance constitutional guarantees of free speech with public interest concerns, including consumer protection, competition, and appropriate content.

Major Regulatory Agencies

Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, three crucial U.S. regulatory agencies have played pivotal roles in shaping American media and its interactions with both the government and the public. These agencies—the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)—each emerged in response to specific challenges presented by the media landscape of their time, and their mandates have adapted significantly to address the complexities of the digital age.

Federal Trade Commission

The first stirrings of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) date back to 1903, when President Theodore Roosevelt established the Bureau of Corporations to investigate the practices of increasingly powerful American businesses and trusts. Recognizing the need for an agency with more sweeping powers to ensure fair competition, President Woodrow Wilson signed the FTC Act into law on September 26, 1914, creating an agency designed to “prevent unfair methods of competition in commerce (Federal Trade Commission).” From its inception, the FTC absorbed the work and staff of the Bureau of Corporations, operating similarly but with additional regulatory authority. In the words of the FTC:

Like the Bureau of Corporations, the FTC could conduct investigations, gather information, and publish reports. The early Commission reported on export trade, resale price maintenance, and other general issues, as well as meat packing and other specific industries. Unlike the Bureau, though, the Commission could…challenge “unfair methods of competition” under Section 5 of the FTC Act, and it could enforce…more specific prohibitions against certain price discriminations, vertical arrangements, interlocking directorships, and stock acquisitions (Federal Trade Commission).

While initially focused on preventing anticompetitive business practices and providing oversight on wartime economic practices, such as advising President Wilson on exports during World War I, the FTC’s role has expanded significantly in recent decades. Today, it is a primary regulator of consumer protection in the digital sphere, actively investigating and prosecuting tech companies for privacy violations, deceptive advertising, and unfair data practices. For instance, the FTC has taken significant actions against social media platforms and data brokers for mishandling user information, reflecting its modern emphasis on protecting consumers in the online economy.

Federal Radio Commission

The Federal Radio Commission (FRC) was established with the passage of the Radio Act of 1927. Its primary purpose was to “bring order to the chaotic situation that developed as a result of the breakdown of earlier wireless acts passed during the formative years of wireless radio communication (Messere).” In the early days of radio, the airwaves were a free-for-all, with stations broadcasting on overlapping frequencies, leading to widespread interference and a poor listening experience. The FRC, comprising five commissioners, was authorized to grant and deny broadcasting licenses, assign frequency ranges, and set power levels for each radio station. While it struggled in its early years to establish clear guidelines for broadcast content, its existence was crucial in laying the groundwork for organized spectrum management. The FRC, however, was a temporary body, and its responsibilities were absorbed by a new, more comprehensive agency in 1934, as indicated in Chapter 7, “Radio.”

Federal Communications Commission

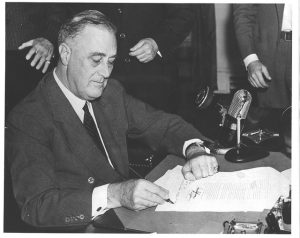

Created by the Communications Act in 1934 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives, the Federal Communications Commission was “charged with regulating interstate and international communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable (Federal Communications Commission).” Its overarching mission was to establish “a rapid, efficient, nationwide, and worldwide wire and radio communication service (Museum of Broadcast Communications).” The FCC’s responsibilities are broad, encompassing everything from licensing broadcast stations and managing spectrum allocation to overseeing telephone services and, increasingly, broadband internet.

Throughout its long history, the agency has enforced numerous laws and regulations impacting media ownership and content. Historically, this included rules like the National TV Ownership Rule, which limited the percentage of the nation’s homes a single broadcaster could reach, and various cross-ownership restrictions designed to prevent media monopolies, such as prohibiting the ownership of a radio station and a TV station in the same market, or a newspaper and a TV station in the same market (PBS, 2004). While some of these specific rules and thresholds have been debated, relaxed, or updated over time to reflect changes in the media landscape and market consolidation, the FCC continues to play a critical role in these areas. More recently, the FCC has been at the center of significant policy debates surrounding net neutrality, advocating for or against regulations that ensure equal access to internet content. It also plays a key role in allocating spectrum for new technologies like 5G, promoting broadband deployment to underserved areas, and enforcing indecency rules on traditional broadcast media, as seen in various high-profile content disputes over the years. The FCC’s ongoing efforts demonstrate the government’s persistent involvement in shaping the communication infrastructure and content environment for the American public.

Regulation Today

The U.S. federal government has long been involved in media regulation, with media in all their forms operating under governmental jurisdiction since the early 1900s. Since that time, regulatory efforts have continuously transformed as new forms of media have emerged and expanded their markets to larger audiences. This ongoing oversight aims to establish and maintain order within the media industry while ensuring the promotion of the public good, balancing constitutional guarantees of free speech with concerns for consumer protection, competition, and content appropriateness.

Today, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) continues to hold the primary responsibility for regulating many aspects of media and telecommunications. At the same time, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) plays a significant, though different, role. Although each commission holds distinct duties, their overarching purpose remains to establish and maintain order in the media industry while ensuring the promotion of the public good. This section examines the modern responsibilities of both commissions and the evolving landscape of antitrust legislation and deregulation.

The Structure and Purposes of the FCC

The FCC is organized into various operating bureaus and staff offices, each with specialized responsibilities. While the specific number and names of these divisions can evolve, their general responsibilities include “processing applications for licenses and other filings; analyzing complaints; conducting investigations; developing and implementing regulatory programs; and taking part in hearings (Federal Communications Commission).” Key bureaus that directly impact media include the Media Bureau, the Wireline Competition Bureau, the Wireless Telecommunications Bureau, and the International Bureau.

The Media Bureau oversees the licensing and regulation of broadcasting services. Specifically, it “develops, recommends, and administers the policy and licensing programs relating to electronic media, including cable television, broadcast television, and radio in the United States and its territories (Federal Communications Commission).” Because it aids the FCC in its decisions to grant or withhold licenses from broadcast stations, the Media Bureau plays a vital role within the organization. These decisions are based on the “commission’s evaluation of whether the station has served in the public interest,” and largely stem from the Media Bureau’s recommendations. The Media Bureau has issued rulings on critical public interest matters, including children’s programming, ensuring educational content and limiting commercialization, and mandatory closed captioning to enhance accessibility for individuals with hearing impairments.

The Wireline Competition Bureau (WCB) concerns itself with “rules and policies concerning telephone companies that provide interstate—and, under certain circumstances, intrastate—telecommunications services to the public through the use of wire-based transmission facilities (Federal Communications Commission).” Despite the increasing market dominance of wireless communications, the WCB maintains a substantial presence within the FCC by “ensuring choice, opportunity, and fairness in the development of wireline telecommunications services and markets (Federal Communications Commission).” Beyond this primary goal, the bureau’s objectives include “developing deregulatory initiatives; promoting economically efficient investment in wireline telecommunications services; and fostering economic growth (Federal Communications Commission).” A notable past action involved the WCB ruling against Comcast regarding the blocking or throttling of online content, which sparked significant public debate about the extent of government authority over internet service providers and large businesses, foreshadowing later net neutrality discussions.

The Wireless Telecommunications Bureau (WTB) represents another prominent bureau within the FCC, serving as the counterpart to the WCB for mobile communications. This bureau oversees mobile phones, pagers, and two-way radios, handling “all FCC domestic wireless telecommunications programs and policies, except those involving public safety, satellite communications or broadcasting, including licensing, enforcement, and regulatory functions (Federal Communications Commission).” The WTB balances the expansion and limitation of wireless networks, registers antenna and broadband use, and manages the radio frequencies for airplane, ship, and land communication. As U.S. wireless communication continues its rapid growth, particularly with the deployment of 5G and future wireless technologies, this bureau is likely to continue increasing in both scope and importance, managing critical spectrum allocation and ensuring reliable wireless services.

Finally, the International Bureau represents the FCC in all matters related to satellite and international communications. This larger organization attempts to “connect the globe for the good of consumers through prompt authorizations, innovative spectrum management and responsible global leadership (Federal Communications Commission).” To prevent international interference, the International Bureau collaborates with partners worldwide on frequency allocation and orbital assignments for satellites. It also concerns itself with foreign investment in the United States, traditionally ruling that outside governments, individuals, or corporations cannot own more than 25 percent of the stock in a U.S. broadcast, telephone, or radio company. However, this threshold can be waived on a case-by-case basis if deemed in the public interest.

The Structure and Purposes of the FTC

While the FCC provides extensive media regulations, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) also plays a significant role in the media industry, primarily through its mandate to eliminate unfair and deceptive business practices. In the course of these duties, it has considerable contact with media outlets, particularly concerning advertising, privacy, and data security. The National Do Not Call Registry, established by the FTC in 2003, exemplifies the FTC’s consumer protection responsibility regarding media. This registry allows consumers to opt out of most telemarketing phone calls, with exemptions for groups such as nonprofit charities and businesses with which a consumer has an existing commercial relationship. Initially intended for landline phones, the Do Not Call Registry was expanded to include wireless telephones, demonstrating the FTC’s adaptability to new communication technologies in its consumer protection efforts. More recently, the FTC has been at the forefront of regulating online privacy, investigating major tech companies for data breaches, deceptive privacy policies, and anti-competitive practices that impact media distribution and advertising.

Role of Antitrust Legislation

As discussed in Chapter 13, “Economics of Mass Media”, the federal government has long regulated companies’ business practices. Over the years, the government has passed several antitrust acts that discourage the formation of monopolies.

During the 1880s, the rise of powerful industrial trusts, such as Standard Oil, which monopolized industries by having stockholders transfer shares to a single board of trustees, spurred congressional action. The enactment of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 was a landmark effort to dissolve such trusts. The Act declared illegal “every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations (Our Documents, 1890).”

The Sherman Antitrust Act served as a crucial precedent for future antitrust regulation. As discussed in Chapter 13, “Economics of Mass Media”, the 1914 Clayton Antitrust Act and the 1950 Celler-Kefauver Act expanded on the principles outlined in the Sherman Act. The Clayton Act helped establish the foundation for many of today’s business and media competition regulatory practices, providing businesses with “fair warning” about the dangers of anticompetitive practices and specifically prohibiting actions that may “substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce (Gongol, 2005).”

The Clayton Act initially had a loophole, as it prohibited mergers but allowed companies to buy individual assets of competitors, which could still lead to monopolies. The 1950 Celler-Kefauver Act closed this loophole by giving the government the power to stop vertical mergers (where two companies in the same business but on different levels, such as a content producer and a distribution platform, combine). It banned asset acquisitions that reduced competition (Financial Dictionary).

These laws reflected growing concerns in the early and mid-20th century that the trend toward monopolization could lead to the extinction of competition and harm the public interest. These robust government regulations of businesses, including media companies, primarily increased until the 1980s, when the United States experienced a significant shift in mindset, and citizens began to call for less governmental power. The U.S. government responded as deregulation became the norm.

Move Toward Deregulation

Media deregulation began in the 1970s as the FCC shifted its approach to regulating radio and television. Initially aimed at clarifying laws to make the FCC run more efficiently and cost-effectively, deregulation truly took off with the arrival of the Reagan administration and its new FCC chairman, Mark Fowler, in 1981. The FCC began overturning existing rules and experienced “an overall reduction in FCC oversight of station and network operations (Museum of Broadcast Communications).” Between 1981 and 1985, lawmakers significantly altered laws and regulations to grant more power to media licensees and reduce that of the FCC. For example, they expanded television licenses from three years to five, and corporations were allowed to own more separate TV stations, eventually leading to the removal of national ownership caps in some areas.

The shift in regulatory control had a powerful effect on the media landscape. Initially, laws had prohibited companies from owning media entities in more than one medium; however, deregulation facilitated consolidation, creating large mass-media companies that increasingly dominated the U.S. media system. For instance, the telecommunications industry, once dominated by a single regulated monopoly (AT&T before its breakup), saw the rise of a few major players (Kimmelman). Similarly, media conglomerates like Viacom (now part of Paramount Global) and Disney own vast portfolios encompassing television stations, film studios, record companies, and streaming services. Bertelsmann, a global media powerhouse, continues to own numerous publishing imprints, television and radio stations, and record companies worldwide (Columbia Journalism Review). Due to this rapid consolidation, concerns about media diversity and market power grew. By the late 1980s, Congress began to slow the FCC’s release of control, leading to a more cautious approach to further deregulation.

Today, deregulation remains a hotly debated topic. Some favor continued deregulation, believing that the public benefits from less governmental control, fostering innovation and competition. Others, however, argue that excessive consolidation of media ownership poses a significant threat to media diversity, localism, and the system of checks and balances, potentially limiting the range of voices and perspectives available to the public. It remains likely that the regulation of media will continue to ebb and flow over the years, as it has since regulation first came into practice, adapting to new technologies, market structures, and prevailing political and public sentiments.

Beyond the Firewall: How Governments Control the Online World

The U.S. federal government has long been involved in the regulation of media, with media in all their forms operating under governmental jurisdiction since the early 1900s. Since that time, regulatory efforts have continuously transformed as new communication technologies have emerged and expanded their markets to larger audiences. This ongoing oversight aims to establish and maintain order within the media industry while ensuring the promotion of the public good, balancing constitutional guarantees of free speech with concerns for consumer protection, competition, and content appropriateness.

Internet censorship, a complex and rapidly evolving issue, is a stark manifestation of the ongoing tension between governmental control and the promise of a free and open internet. While the debate between search engines like Google and nations such as China has long been a prominent example, internet censorship occurs on a much more widespread level, affecting people in virtually every country, including those not typically associated with strict authoritarian regimes. Today, various online services and initiatives provide increasing transparency into these practices, allowing users to understand the extent and nature of online restrictions globally.

Google’s Transparency Report, launched in 2010 and continuously updated, serves as a crucial tool for illuminating online censorship worldwide. This program enables users to view data on government requests for content removal and user information. It details the number of times a country requests the removal of specific data, the type of content they want removed, and the percentage of requests that Google complies with. In some cases, these requests involve minor infractions, such as YouTube videos that violate copyright or contain hate speech, which platforms are often legally or ethically obligated to address. In other, more significant cases, social media companies and search engines have faced formidable demands from governments seeking to suppress dissent or control narratives. For instance, following the disputed 2009 elections, Iran blocked all of YouTube, and Pakistan famously blocked the site for over a year (from 2012 to 2016) in response to content deemed blasphemous.

The scope of censorship extends beyond overtly authoritarian states. Countries not usually associated with strict censorship also engage in content restrictions based on their national laws and cultural norms. Germany, for example, has consistently requested the removal of content affiliated with neo-Nazism, Holocaust denial, or other illegal extremist ideologies, reflecting its strong laws against such material. Thailand frequently requests the removal of content deemed offensive to its monarchy under strict lèse-majesté laws. Even in countries with robust free speech protections like the United States, government agencies regularly request user information from tech companies for law enforcement purposes, and occasionally request content removal, often related to child exploitation, national security threats, or intellectual property infringement. While the percentage of compliance varies, it underscores that no country is entirely free from government influence on online content.

According to Google and other independent monitoring organizations, internet censorship has become increasingly commonplace and sophisticated every year. Governments are employing a wider array of tactics, moving beyond simple website blocking to more subtle methods like content filtering, throttling, and the weaponization of disinformation. A spokesperson for Google has consistently articulated the company’s position, stating that “The openness and freedom that have shaped the internet as a powerful tool have come under threats from governments who want to control that technology.” By providing users with access to censorship numbers and trends, Google and similar transparency initiatives aim to enable the public to witness the extent of internet censorship that occurs in their daily lives and to foster greater awareness and, potentially, citizen outrage.

The rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has introduced new complexities and challenges to the landscape of internet censorship. AI-powered algorithms are increasingly used by platforms for content moderation, automatically detecting and removing content that violates terms of service, including hate speech, misinformation, and illegal material. While this can be a tool for efficiency, it also raises concerns about algorithmic bias, lack of transparency, and the potential for over-censorship or the suppression of legitimate speech. Governments are also exploring how AI can be leveraged for more sophisticated forms of censorship, such as automated content filtering at national borders or the generation of pro-government narratives to counteract dissenting voices. Conversely, AI can also be a tool for circumventing censorship, with AI-powered VPNs or content generation tools potentially helping users bypass restrictions. The interplay between AI, content moderation, and government control is a rapidly evolving frontier, with significant implications for the future of online freedom and access to information.

As censorship efforts become more pervasive and technologically advanced, many predict that the public’s awareness and concern will also rise. The future of internet censorship may continue to grow in complexity and scope. Still, for now, at least, the public can be aware of the extent of the practice and the ongoing global struggle for digital freedom.