15.3 The Law and Mass Media Messages

The discourse on media law, which has been ongoing since the inception of the first U.S. media industry laws in the early 1900s, is deeply rooted in the historical context of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This context is crucial, as it provides a deeper understanding of the liberties guaranteed under the First Amendment, particularly the freedom of the press, which is at the heart of the debate. The significance of these rights cannot be overstated, as they form the foundation of media law and continually shape the ongoing discourse on how information is created, distributed, and consumed in a rapidly evolving landscape.

The First Amendment

A foundational tenet of modern governance posits that democracy cannot truly exist without open communication. This principle asserts that a robust and transparent exchange of ideas, information, and opinions is not merely beneficial but essential for a self-governing populace to make informed decisions. This open communication is understood to protect all forms of expression, even ideas that many might find deeply offensive or repugnant, such as those propagated by groups like the Westboro Baptist Church, whose controversial protests test the very limits of free speech. The rationale is that suppressing even offensive speech sets a dangerous precedent that can eventually be used to silence dissenting or critical voices, thereby eroding the democratic process.

Thomas Jefferson, a principal architect of American democracy, famously articulated this idea, stating, “Information is the currency of democracy.” He further underscored the vital role of the press by proclaiming, “Were it left for me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” These quotes encapsulate the deep-seated belief among the U.S. Founding Fathers that a free and unfettered press is indispensable for holding power accountable and informing citizens.

This robust protection of speech, particularly press freedom, is enshrined in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” This constitutional guarantee provides a unique level of protection for expression that is largely absent in the constitutions of most other countries, which often include provisions for free speech but typically with more explicit limitations based on national security, public order, or reputation.

Historically, the full protections afforded by the First Amendment were extended primarily, and at one point almost exclusively, to print media. This distinction arose from the perceived unlimited nature of print publications and the deep-rooted tradition of a free press. This broad protection for newspapers was definitively affirmed by the 1974 Supreme Court ruling in Miami Publishing Co. v. Tornillo. In this landmark case, the Court unanimously ruled that a Florida statute requiring newspapers to provide reply space to political candidates they criticized was unconstitutional. The Court reasoned that compelling newspapers to publish specific content infringed upon their editorial independence, amounting to an unconstitutional “right-of-reply” that violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. This pivotal decision solidified the principle that newspapers retain editorial control and do not have to give space to candidates or individuals they criticize, reinforcing their autonomy over their content.

In stark contrast, television and radio broadcasters have historically been, and to some extent still are, subject to different and more stringent regulations. This disparate treatment stems from the concept of spectrum scarcity, the idea that the broadcast airwaves are a finite public resource. Because not everyone can broadcast due to limited frequencies, the government has historically regulated broadcast licenses in the “public interest.” This obligation has, at times, required TV and radio stations to provide reply time or cover controversial issues with a degree of balance.

The concept of prior restraint, which refers to government censorship of speech or publication before it occurs, stands as one of the most severe infringements on First Amendment freedoms in the United States. The Supreme Court has historically viewed prior restraints with extreme skepticism, creating a very high bar for their permissible use.

A foundational case in establishing this principle was 1931’s Near v. Minnesota. This case involved newspaper publisher Jay Near, whose paper, The Saturday Press, regularly published highly inflammatory, racist, and anti-Semitic charges against local officials and groups. In response, a Minnesota court issued an injunction stopping Near from publishing his paper, claiming the material was “malicious, scandalous, and defamatory” under a state nuisance law. However, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a narrow 5-4 decision, overturned the Minnesota court’s action. The Court’s ruling was pivotal, establishing that prior restraint could only be used in scarce and exceptional circumstances to suppress specific types of content. These narrow exceptions were defined as: military information during a time of war, incitement to overthrow the government, and obscenity. This landmark case effectively established that virtually all content, even that which is offensive or disagreeable, is protected by the First Amendment and cannot be censored by the government before publication.

The principle of prior restraint was rigorously tested again in the context of The Pentagon Papers in 1971. Daniel Ellsberg, a former military analyst, leaked a highly classified Department of Defense report on U.S. Vietnam policy to The New York Times and later to The Washington Post. Ellsberg contended that the leaked documents were embarrassing to the government but contained no legitimate secrets that would harm national security. The Nixon administration, however, argued that their publication posed a grave danger to national security and successfully obtained restraining orders against The New York Times and other newspapers, temporarily keeping the story unpublished for two weeks. The case rapidly ascended to the Supreme Court. In a per curiam decision, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that the government had failed to meet the heavy burden of proof required to justify prior restraint. The Court emphasized that the public’s need for an “informed and enlightened citizenry” regarding government conduct, especially on matters of war, significantly outweighed the government’s desire for secrecy. This case powerfully reaffirmed the high bar set by Near v. Minnesota and solidified the press’s ability to publish even classified information unless it presents a clear and immediate danger.

Another notable instance involving prior restraint concerns The Progressive magazine. In 1979, the magazine attempted to publish an article detailing how a hydrogen bomb worked, claiming that the story was entirely based on publicly available information. The U.S. government, however, sought to prevent its publication, arguing it would aid nuclear proliferation. A district court issued a restraining order against the magazine, citing national security concerns. However, before the case could be fully litigated, other authors independently published much of the same information contained in The Progressive article, rendering the original order moot. The government eventually dropped its case, and the article was published. This episode further demonstrated the difficulty of imposing prior restraint, especially when the information is not genuinely secret or is already in the public domain.

A more relevant recent example, though not a Supreme Court case and not a classic prior restraint on a news organization, involves the U.S. government’s efforts to prevent former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden from publishing his memoir, Permanent Record, in 2019 without a pre-publication review. The Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Snowden, arguing he violated non-disclosure agreements by publishing the book without submitting it for government review. While the book was already published by the time the lawsuit was filed, the government sought to seize all profits, which serves as a chilling effect on future publications. This highlights a modern form of “prior restraint by proxy” or “prior review” that governments attempt to impose on individuals with access to classified information, rather than directly on the press, but which still impacts the flow of information to the public. The core legal and ethical tension remains: how to balance national security interests with the public’s right to information and the First Amendment’s robust protections against censorship.

The First Amendment and its application guide how information gets presented in society. The press’s critical role in disseminating this information has led to its informal designation as the “Fourth Estate.” This term indicates that the media operates as a de facto fourth branch of government, serving as an independent watchdog over the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. It scrutinizes power, exposes wrongdoing, and facilitates public discourse, acting as a crucial check and balance in the democratic system.

However, challenges to this open communication can arise, particularly through a phenomenon known as the chilling effect. This occurs when journalists or other media professionals refrain from covering particular stories, engaging in certain types of reporting, or expressing certain viewpoints due to fear of reprisal, punishment, or legal consequences (such as being jailed, fined, or subjected to burdensome lawsuits). For example, suppose a government repeatedly threatens or arrests journalists for reporting on sensitive issues. In that case, other journalists might self-censor to avoid similar fates, even if their reporting is truthful and in the public interest. Such tactics, intended to control information, usually anger the public when they become known and significantly damage the government’s reputation and its perceived commitment to democratic principles, ultimately undermining the very open communication essential for democracy.

The Courtroom Conundrum: Press Rights vs. Fair Trials

The fundamental rights enshrined in the U.S. Constitution often intersect, and sometimes conflict, creating complex legal and ethical dilemmas. One of the most prominent areas of conflict arises between the right to a free press, guaranteed by the First Amendment, and the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a fair trial. This tension often surfaces because extensive pretrial media coverage can make it exceptionally difficult to find an impartial jury, as potential jurors may have already formed opinions based on news reports, social media discussions, or public sentiment.

A landmark case illustrating this conflict is the 1966 Sam Sheppard Fugitive case. Dr. Sam Sheppard, a prominent Ohio physician, was convicted of murdering his pregnant wife in a highly sensationalized trial in the 1950s. The media coverage was pervasive and often inflammatory, with newspapers publishing speculative stories and details about his personal life. After years in prison, Sheppard’s case reached the Supreme Court, which ultimately overturned his conviction. The Supreme Court ruled that the trial judge had failed to protect Sheppard from the massive, prejudicial publicity that surrounded his trial, thereby denying him a fair trial. This ruling established a crucial precedent: while the judge cannot directly stop media coverage of a trial due to the First Amendment’s protections, it is the judge’s job to ensure a fair trial for the defendant by actively mitigating the effects of prejudicial publicity.

To achieve this, judges have several tools at their disposal. These include issuing a gag order, which prohibits participants in a trial (such as attorneys, witnesses, or even law enforcement) from speaking publicly about the case; sequestering the jury, meaning the jury is isolated from outside influences for the duration of the trial; postponing the trial until public excitement has subsided; changing the venue of the trial to a location less affected by pretrial publicity; or, as a last resort, ordering a new trial if prejudice cannot be overcome. For instance, in high-profile criminal cases like the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing trial, judges often implement strict gag orders and extensive jury selection processes to ensure impartiality amidst widespread media attention.

Related to these issues is the debate over cameras in the courtroom. Historically, cameras were banned mainly from courtrooms following the infamous 1935 trial of Bruno Hauptmann for the Lindbergh kidnapping. The presence of numerous photographers and newsreel cameras turned the courtroom into a chaotic “circus atmosphere,” severely disrupting the proceedings and raising concerns about the dignity and fairness of the judicial process. This led to a widespread ban on cameras in both federal and many state courts. However, with the advent of new technology, still and television cameras became significantly less intrusive, smaller, and quieter. This technological evolution gradually led to a shift in policy. Today, cameras are allowed in many state courts on a case-by-case basis, often at the discretion of the presiding judge, who weighs the public’s right to access against the potential for disruption or prejudice. Despite this trend, cameras are notably not permitted in the U.S. Supreme Court, maintaining a tradition of oral argument transcripts and audio recordings rather than live video. This ongoing debate reflects the persistent tension between press freedom, judicial integrity, and the right to a fair trial.

The First Amendment and Commercial Speech

Commercial speech, defined as speech that proposes a commercial transaction, has historically been afforded less protection under the First Amendment than other forms of expression, such as political or artistic speech. The rationale for this lesser protection stems from the idea that its primary purpose is economic, rather than contributing to the marketplace of ideas in the same way.

This diminished protection was famously established in 1942’s Valentine v. Chrestensen. In this case, F.J. Chrestensen owned a surplus U.S. Navy submarine and attempted to distribute handbills advertising tours of the submarine in New York City. When police ordered him not to distribute the leaflets, citing anti-littering ordinances, he added a political protest message on the back of the handbill. The Supreme Court, however, sided with the police, ruling that the First Amendment did not protect the “purely commercial advertising” aspect of the leaflet. This landmark decision effectively created a two-tiered system of speech protection, with commercial speech occupying a lower tier.

Given this context, it’s notable to consider the legal landscape of advertising certain products. The only legal good that historically cannot be advertised on broadcast television and radio in the United States is tobacco. This ban, enacted in 1971, reflects a public health consensus that the societal harm caused by tobacco products outweighs the commercial speech rights of tobacco companies on these specific platforms. However, it is generally permissible to advertise smoking accessories, as these products do not carry the same direct health risks as the tobacco itself.

The question of marijuana advertising presents a contemporary challenge to these principles. While marijuana has been legalized for recreational or medicinal use in a growing number of states, it remains federally illegal. This creates a complex patchwork of regulations, allowing the promotion of sales within states where it is legal. Still, any promotion across state lines or through federally regulated channels (like broadcast, which is subject to federal law) can be problematic. The fundamental rule remains that it is illegal to promote the sale of illicit drugs, even if those drugs might be legal under specific state laws. This tension highlights the ongoing complexities of commercial speech regulation in a dynamic legal and social environment.

Beyond specific product categories, the regulation of offensive advertising is not overseen by a single, overarching government agency. Instead, what constitutes “offensive” is often subjective and can be challenged by various groups. While some ads might push boundaries, many companies ultimately choose to abandon ads in the wake of significant public criticism or backlash, even if the ads are not technically illegal. This self-regulation is driven by concerns for brand reputation, consumer loyalty, and potential financial losses that can result from alienating their target audience. For example, numerous advertising campaigns, ranging from fashion brands to fast-food chains, have been pulled due to public outcry over perceived insensitivity, objectification, or cultural appropriation, demonstrating that public opinion often serves as a powerful, albeit informal, regulator of commercial speech ethics.

Media Law in the United States

Traditionally, media law was often segmented into two primary areas: telecommunications law, which regulated radio and television broadcasts, and print law, which governed publications such as books, newspapers, and magazines. However, with the pervasive convergence of media platforms and the dominance of the internet, these distinctions have increasingly blurred. Many media laws now apply across various digital and traditional forms, though some historical nuances persist. This section examines several key areas of media law that continue to shape the relationship between media messages and legal frameworks, including privacy, libel and slander, copyright and intellectual property, freedom of information, and equal time and coverage.

Privacy in media law addresses the individual’s right to control information about themselves and to be free from unwanted intrusion. In 1974, Congress passed the Privacy Act, which “protects records that can be retrieved by personal identifiers such as a name, social security number, or other identifying number or symbol (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services).” While it primarily protects records held by federal agencies that contain personal identifiers, its scope does not directly regulate private media entities. Instead, media privacy law largely stems from common law principles and state statutes, focusing on torts such as intrusion upon seclusion, public disclosure of private facts, false light, and appropriation of likeness. Journalists and media personnel must exercise considerable care to avoid revealing specific private information about an individual without their permission, even if the information is factually accurate, especially when it is not a matter of legitimate public concern.

The rise of social media and the ease with which private information can become public have intensified these challenges. Recent high-profile cases often involve celebrities or public figures whose private lives become intertwined with public interest, leading to complex legal battles over the boundaries of privacy in the digital age. For instance, disputes frequently arise when paparazzi capture images in private settings or when personal communications are leaked and subsequently published by media outlets, testing the limits of what constitutes a “newsworthy” private fact.

Libel and Slander

Libel and slander are critical areas of media law concerning defamation, which involves false statements that harm an individual’s reputation. Libel refers to written or broadcast defamation, while slander refers to spoken defamation (Media Law Resource Center). While state jurisdictions primarily govern defamation laws, most states enforce largely consistent statutes across the United States.

Irresponsible reporting can have severe consequences in the realm of media law. When journalists fail to report responsibly, the legal and financial repercussions can be devastating. For public figures, the standard for proving defamation is exceptionally high, established in the landmark Supreme Court case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. This ruling requires public figures to prove not only that the defamatory statement was false and damaging, but also that it was made with “actual malice”—meaning the publisher knew the information was false or acted with reckless disregard for the truth. This high bar was set to protect robust public debate and investigative journalism. For private individuals, the standard for proving defamation is generally lower, often requiring only proof of negligence, as clarified in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., which distinguished between public and private figures in defamation cases. A very recent and high-profile example illustrating the severe consequences of alleged reckless disregard for the truth is the Fox News Network, LLC v. Dominion Voting Systems, Inc. defamation lawsuit, which resulted in a significant settlement for Dominion, highlighting the substantial financial risks media organizations face when accusations of actual malice are credibly made.

The Truth Shall Set You Free: America’s Libel Legacy

The bedrock of American libel law, and a stark deviation from the libel traditions of many other nations, can be traced back to a pivotal colonial case: the John Peter Zenger trial of 1735. Zenger, a printer and publisher of the New York Weekly Journal, found himself at the center of a landmark legal battle after his newspaper published scathing articles accusing the corrupt New York Governor William Cosby of various abuses of power, including replacing New York Supreme Court justices when they dared to disagree with him. Infuriated by the criticism, Governor Cosby had Zenger thrown in jail on charges of seditious libel – a crime under English common law that essentially criminalized any published criticism of government, regardless of its veracity.

Zenger’s defense, mounted by the brilliant Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton, was revolutionary for its time: he argued that the charges were actual and, therefore, could not be libelous. Under prevailing English law, the truth of a statement was irrelevant; the mere act of publishing something critical of authority was enough to constitute libel. Defying the explicit instructions of the judge, the jury found Zenger “not guilty,” a verdict that, while not immediately overturning existing law, symbolically established truth as a robust defense against libel in American jurisprudence. This principle, that factual statements cannot be libelous, stands in sharp contrast to the legal landscape in countries like England, where an individual can sometimes successfully sue for libel even if the statements that damage a person’s reputation are demonstrably factual, if those statements are found to have caused harm without sufficient public interest justification.

Beyond truth, American libel law recognizes several other key defenses. One such defense is privilege. This protects statements made by officials in government meetings, in court proceedings, or within government documents, even if those statements might otherwise be considered defamatory. This “absolute privilege” is a strong defense because it ensures that those participating in official governmental or judicial processes can speak freely without fear of being sued for libel, promoting transparency and the effective functioning of public institutions. For example, a judge’s comments during a trial, or a senator’s speech on the floor of Congress, are protected by privilege.

Another vital defense is opinion. Statements that are identifiable as opinions cannot be libelous because opinions are inherently neither true nor false; they are subjective interpretations or beliefs. The challenge often lies in distinguishing opinion from factual assertion. For instance, a critic writing that a play is “the most boring production I’ve ever seen” is likely expressing an opinion, whereas stating that “the play uses stolen lines from another playwright” would be a factual claim that could be libelous if false. The protection of opinion is crucial for freedom of expression and robust public discourse, allowing for spirited debate and critique without fear of litigation simply for expressing a viewpoint.

Copyright and Intellectual Property

Copyright and Intellectual Property law governs the rights of creators over their original works. This includes literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, as well as software, films, digital content, and even architectural designs. Once a job is created and fixed in a tangible medium, it automatically receives copyright protection, granting the owner exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, perform, display, and adapt their work (Citizen Media Law Project). After a specific period, a copyright expires, and the work enters the public domain, becoming freely available for public use.

Copyright does not, however, protect facts, which are essential for news media. Despite the time and effort it takes to uncover facts, no individual or company can claim ownership of them; anyone may repeat facts as long as they do not copy the specific expression (the written story or broadcast) of the source. The digital age has introduced unprecedented challenges to copyright enforcement due to the ease of digital copying, peer-to-peer file sharing, and the proliferation of user-generated content.

In the realm of copyright law, the public domain refers to the body of creative works and inventions that are not protected by intellectual property rights, meaning they can be freely used, adapted, and distributed by anyone without permission or payment. This entry into the public domain typically occurs after a specific period set by copyright law, which in the United States, for works created from 1978 onward, is generally the life of the author plus 70 years, and for corporate works or works made for hire, 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter. The annual shift of works into the public domain brings a wealth of creative material that can inspire new art, literature, and media.

Recently, several iconic titles and characters have shed their copyright protection and entered the public domain, opening them up for reinterpretation. A significant milestone occurred on January 1, 2024, when Steamboat Willie, the 1928 Walt Disney animated short film featuring the earliest versions of Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse, entered the public domain. This meant that the specific, non-speaking, black-and-white iterations of these beloved characters could be freely used and adapted by creators, leading to an immediate proliferation of independent films, games, and merchandise featuring these early designs. Similarly, also in 2024, the original version of Tigger from A.A. Milne’s The House at Pooh Corner (1928) joined other Winnie-the-Pooh characters (like Pooh and Piglet, whose 1926 versions entered the public domain in 2022) in the public domain. This has similarly led to independent horror films and other creative works that reimagine these classic characters in ways that would have previously been impossible due to copyright restrictions. Other notable entries in recent years include F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (2021) and Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (2022).

Looking ahead, the next five years will see even more popular titles and characters transition into the public domain, promising another wave of creative reinterpretations. In 2025, works from 1929 will enter the public domain. This includes iconic films like The Hollywood Revue of 1929, which featured early Technicolor sequences, and potentially more early animated shorts from various studios. Moving into 2026, works from 1930 will become free to use. This could include early sound films from the Golden Age of Hollywood, as well as more pulp fiction characters. The year 2027 will see 1931’s copyrighted works enter the public domain, potentially bringing with them early detective stories and comedies. In 2028, works from 1932 will become available, which might include significant literary works or early iterations of characters that have since become famous. Finally, in 2029, works from 1933 will transition. This year is particularly anticipated because it will mark the public domain entry of the original King Kong. While later iterations and specific design elements from subsequent films will remain copyrighted, the core giant ape character and narrative from the 1933 classic will be open for adaptation, potentially leading to new movies, books, and games exploring the iconic monster’s story without licensing fees. These upcoming entries continue to fuel a vibrant ecosystem of derivative works, allowing new generations of creators to build upon the cultural heritage of the past.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act

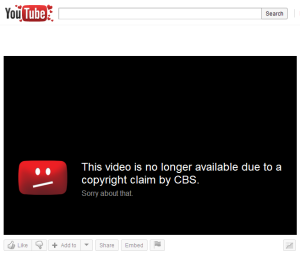

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998 was enacted to address online infringement, notably by providing “safe harbor” provisions for online service providers. These provisions protect platforms from liability for user-posted content if they promptly remove infringing material upon receiving a valid notice from the copyright holder. This was famously affirmed in Viacom v. YouTube, where the court ruled in favor of YouTube, stating it qualified for DMCA protection as it was not obligated to proactively monitor every user-uploaded video for infringement, only to remove content upon notification.

The Music Modernization Act

The rise of streaming services and digital music distribution necessitated further legal modernization. Passed in 2018, the Music Modernization Act (MMA) was a significant bipartisan effort to update U.S. copyright law for the digital era, particularly benefiting songwriters, artists, and music publishers. The MMA created a new Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC) to administer a blanket mechanical license for digital audio uses, making it easier for streaming services to license music and ensuring songwriters and publishers are paid accurately. It also addressed the licensing of pre-1972 sound recordings, bringing them under federal copyright protection, and improved royalty collection for producers and engineers. Beyond the MMA, streaming services operate under complex licensing agreements with record labels, publishers, and performance rights organizations (PROs) like ASCAP and BMI, which collect and distribute public performance royalties for musical works. The advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) further complicates copyright, raising novel questions about the copyrightability of AI-generated content, the legality of using copyrighted works to train AI models, and potential infringement when AI output closely resembles existing protected works.

Freedom of Information Act

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), signed into law in 1966 by President Lyndon B. Johnson, was a significant step towards promoting government transparency. By requiring full or partial disclosure of U.S. government information and documents, FOIA plays a crucial role in helping the public, including journalists, track the government’s actions, from local campaign expenditures to the management of federal tax revenues. This information is vital for news media, ensuring they are well-informed and able to hold the government accountable. While FOIA covers a wide range of federal agencies, some offices are exempt, including documents from the current President, Congress, or the judicial branch (Citizen Media Law Project). Despite these exemptions and the often-complex procedures for accessing information, FOIA remains a powerful tool for transparency. Journalists often receive benefits like fee waivers and expedited processing due to the public interest nature of their requests (Citizen Media Law Project).

The Equal Time Rule

Rules governing political communication in broadcast media aim to ensure fairness. The Equal Time Rule, enshrined in Section 315 of the Communications Act of 1934, requires radio and television stations to give equal opportunity for airtime to all legally qualified political candidates. This means if one candidate uses a station’s facilities, their opponents must be offered comparable time at the same rate. Passed by Congress in 1927 as the equal opportunity requirement, it represented the first major federal broadcasting law, reflecting early fears that broadcasters could manipulate elections. While the law ensures equal access to airtime, it does not regulate campaign funding, meaning well-funded candidates who can afford to pay for airtime still have an advantage. Exemptions exist for bona fide news programs, interviews, and documentaries, allowing media outlets to report on a candidate’s activities without having to cover those of every opponent. Presidential debates also fall under this exemption, often leading to the exclusion of third-party candidates. Section 315 also prohibits media from censoring what a candidate says or presents on air, a principle that has led to controversies when stations are compelled to air controversial campaign ads (Museum of Broadcast Communications).

The Fairness Doctrine

The Fairness Doctrine, enacted in 1949, was a separate FCC policy that required broadcasters to present controversial issues of public importance in a fair and balanced manner. The FCC thus instituted the Fairness Doctrine to “ensure that all coverage of controversial issues by a broadcast station be balanced and fair (Museum of Broadcast Communications).” The FCC viewed station licensees as “public trustees” with an obligation to provide a reasonable opportunity for discussion of contrasting points of view on controversial issues and to seek out issues important to their community actively.

However, some journalists and critics argued that the Fairness Doctrine infringed on First Amendment rights and led to a chilling effect on speech, as broadcasters might avoid controversial topics altogether to avoid the burden of finding opposing viewpoints. The Reagan administration dissolved the doctrine during its 1980s deregulatory efforts. The absence of the Fairness Doctrine means that news organizations, particularly on cable television and the internet, are no longer legally obligated to present all sides of an issue. This has contributed to the rise of highly partisan news outlets, such as Fox News and MSNBC, which often cater to specific political viewpoints without a legal requirement for balance. When a news organization does not make a genuine attempt to provide all sides of an issue, it can lead to a more polarized media landscape, where audiences are exposed primarily to information that confirms their existing biases, potentially hindering informed public discourse and contributing to societal division.

Shield Laws

The concept of shield laws represents a crucial protection for journalists, aiming to safeguard the confidential relationships between reporters and their sources. These laws grant journalists a privilege, akin to attorney-client or doctor-patient confidentiality, exempting them from being compelled to testify in court about their stories and, crucially, about the identities of their confidential sources. The rationale behind shield laws is that without such protection, sources, particularly those exposing wrongdoing or sensitive information, would be less willing to come forward, thereby hindering the press’s ability to inform the public and hold power accountable.

While many U.S. states have enacted their shield laws, providing varying degrees of protection to journalists within their jurisdictions, there is no current federal shield law in the United States. This absence at the federal level means that journalists covering federal investigations or facing federal subpoenas lack a consistent, nationwide legal protection for their sources. The consequences of this gap can be severe, as dramatically illustrated by the case of New York Times reporter Judith Miller. In 2005, Miller was jailed for 85 days for refusing to testify before a federal grand jury about her confidential source in the investigation into the leak of CIA operative Valerie Plame’s identity (the “Plamegate” scandal involving Scooter Libby, then-chief of staff to Vice President Dick Cheney). Her incarceration highlighted the legal vulnerability of journalists operating without federal shield law protection and underscored the tension between press freedom and the government’s investigative powers.

The evolving media landscape has further complicated the application of shield laws, leading to a pressing debate: should shield laws protect bloggers and other non-traditional journalists? The question is tricky to answer definitively, as courts across the country have ruled in different ways, creating a patchwork of legal interpretations. Some courts apply a functional definition, extending protections to anyone engaging in acts of journalism, regardless of their professional affiliation or platform. Others maintain a stricter view, limiting protection to individuals working for established news organizations. This ambiguity poses a significant challenge, particularly as the lines blur between professional journalists, independent bloggers, citizen reporters, and online content creators.

For instance, the question of whether an entity like WikiLeaks would receive shield law protection is particularly contentious. Given its structure and modus operandi of publishing leaked classified information, some legal arguments could be made for its journalistic function, potentially bringing it under the umbrella of shield law protections in specific interpretations. However, it’s highly likely that the American government, which has vigorously pursued legal action against individuals associated with WikiLeaks for leaking classified information, would strongly oppose such a designation, viewing it as a threat to national security rather than a protected journalistic endeavor. The lack of a clear, comprehensive federal shield law leaves this critical question open to ongoing legal battles and interpretation, with significant implications for how information flows in the digital age.