15.6 Digital Democracy and Its Possible Effects

Digital democracy, often referred to as e-democracy, has become an increasingly integral part of political discourse and civic engagement. This phenomenon, which leverages online tools to involve citizens in government and political action, has evolved significantly since its early days, aiming to broaden participation in the democratic process. The belief that the Internet is a highly effective means of engaging individuals in politics has only strengthened over time, with online political organizations attracting millions of members, raising substantial funds, and becoming a pivotal force in electoral politics (Hindman, 2008). Modern election cycles consistently demonstrate how candidates can harness the Internet to significant effect, transforming campaign strategies and voter interaction.

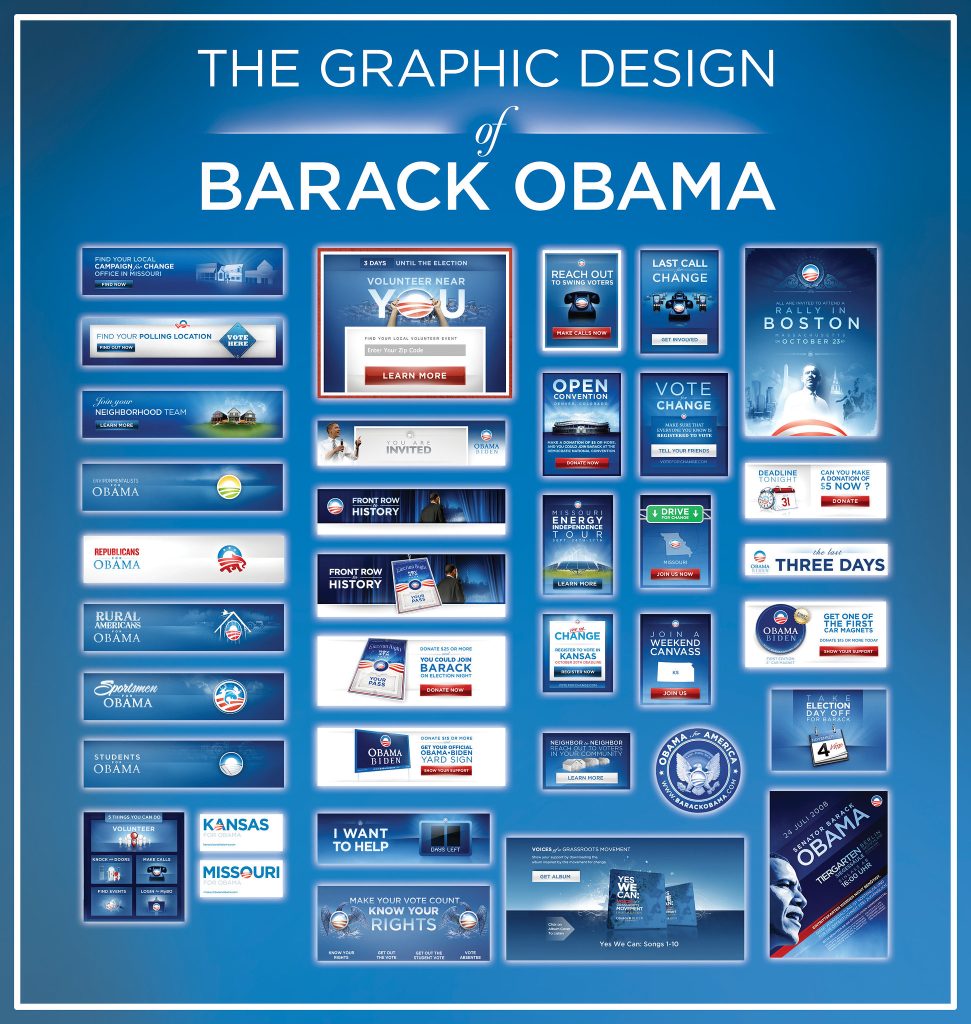

President Obama’s Digital Campaign and Its Enduring Legacy

President Obama’s Digital Campaign: The 2008 presidential campaign of Barack Obama was a watershed moment in the use of digital democracy. His victory in the Democratic presidential primaries on June 8, 2008, was a testament to the power of digital technology. The New York Times, in its article titled “The Wiki-Way to the Nomination,” attributed Obama’s success to his innovative use of the Internet: “Barack Obama is the victor, and the Internet is taking the bows (Cohen, 2008).”

Other political campaigns had used the Internet before Obama. Another Democratic presidential hopeful, Howard Dean, famously built his campaign online during the 2004 election cycle. However, the Obama campaign fully leveraged the possibilities of digital democracy and ultimately secured the Oval Office, in part, on the strength of that strategy. As one writer puts it, “What is interesting about the story of his digital campaign is how digital was integrated fully into the Obama campaign, rather than being seen as an additional extra (Williams, 2009).” President Obama’s successful campaign serves as an excellent example of the possibilities of digital democracy.

Evolving Digital Platforms and Outreach

The evolution of digital political engagement has seen a transformation from traditional websites to a multifaceted approach encompassing social networking, email outreach, text messaging, and viral content.

Traditional Websites

In the early 2000s, political websites like MoveOn.org, founded in 1998, played a crucial role in mobilizing citizens for Democratic causes, encouraging voting, lobbying, and fundraising. These platforms demonstrated the power of online communities in shaping political discourse and action.

Building on this, the Obama campaign established a robust online presence, exemplified by its central hub, MyBarackObama.com. While specific campaign sites may become defunct post-election, the concept of a dedicated digital platform remains central. For instance, modern campaigns and political organizations consistently maintain comprehensive websites that serve as central repositories for information, policy stances, volunteer sign-ups, and donation portals. These sites often feature interactive elements, live streams of events, and direct links to social media profiles, reflecting a continued emphasis on a strong foundational web presence.

Social Networking

The 2008 election highlighted the burgeoning influence of social media platforms, with Facebook emerging as a primary channel for digital outreach. Obama’s official Facebook page garnered millions of followers, and the administration continued to use it for communication. Beyond official pages, supporter-created groups like “Mamas for Obama” and “Women for Obama” demonstrated the organic, grassroots power of social networks. Today, social networking is an indispensable component of political campaigns at all levels.

Platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube are critical for disseminating messages, engaging with voters, and responding rapidly to political developments. For example, Vice President Kamala Harris has been actively involved with various social media platforms, utilizing them for policy discussions, town halls, and direct communication with constituents. Her team frequently uses Instagram for behind-the-scenes glimpses and policy explainers, and X for timely updates and interactions. Similarly, President Donald Trump actively uses Truth Social as a primary platform to advocate for his political agenda and communicate directly with his supporters, showcasing the diverse landscape of social media in modern politics. The sheer reach and immediacy of these platforms make them invaluable for shaping public opinion and mobilizing support, though they also present challenges related to misinformation and polarization.

E-Mail Outreach

The Obama campaign’s masterful use of email outreach was a significant factor in its success. Millions of individuals signed up for updates, receiving concise, personalized emails—often directly from Obama or other key figures like Michelle Obama—that fostered a sense of authenticity and connection. This strategy was not only effective in reaching target audiences with tailored messages but also proved highly successful in fundraising. The campaign raised over $500 million online through these efforts.

This practice has become standard in political fundraising and communication. Modern campaigns leverage sophisticated data analytics to segment email lists, personalize content, and optimize timing for maximum engagement and donations. For example, following President Biden’s withdrawal from the 2024 presidential race, Kamala Harris reportedly saw a record-breaking surge in donations, hauling in over $200 million within a short period, much of which was facilitated through highly targeted email fundraising campaigns. This demonstrates the continued potency of email as a direct and effective tool for both communication and financial support.

Text Messaging

Text messaging, or SMS, also played a crucial role in the 2008 campaign. Supporters received timely updates, including the announcement of Obama’s running mate Joe Biden, through text messages. This direct and immediate communication channel allowed the campaign to mobilize supporters rapidly and share breaking news.

Today, text messaging remains a powerful tool for campaigns, used for voter reminders, event invitations, fundraising appeals, and real-time updates from candidates. Political action committees and campaigns frequently use peer-to-peer texting services to engage in more personalized conversations with potential voters.

E-Democracy in the Age of AI and Deepfakes

The broader concept of e-democracy extends beyond official campaign efforts to include grassroots movements and viral content created by supporters. Websites such as Barackobamaisyournewbicycle.com, a gently mocking site, “listing the many examples of Mr. Obama’s magical compassion. (‘Barack Obama carries a picture of you in his wallet’; ‘Barack Obama thought you could use some chocolate’),” emerged, but a variety of viral videos offered even stronger examples of Obama’s grassroots campaign (Cohen, 2008).

One example of a supporter-created video was “Barack Paper Scissors,” an interactive game inspired by the classic rock-paper-scissors game. Posted on YouTube, the footage logged some 600,000 views during the campaign. The success of videos such as “Barack Paper Scissors” did not go unnoticed by the Obama campaign. Most memorably, the “Yes We Can” video, featuring will.i.am, which set Obama’s words to music, garnered tens of millions of views and was even integrated into the official campaign website, illustrating the power of user-generated content in amplifying a message.

However, the modern e-democracy landscape is significantly more complex, particularly with the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and deepfakes. AI-powered analytics can now be used for highly sophisticated voter targeting and micro-targeting, enabling campaigns to deliver hyper-personalized messages based on vast datasets of individual preferences and behaviors. This raises concerns about privacy and the potential for manipulation.

More alarmingly, the emergence of deepfakes—realistic but fabricated audio and video content—poses a profound threat to democratic processes. These AI-generated fakes can be used to spread disinformation, discredit opponents, or sow discord, making it increasingly difficult for the public to discern truth from fabrication. The 2016 Russian interference in the US presidential election, which heavily leveraged social media to spread divisive content and disinformation, serves as a stark historical example of how digital platforms can be weaponized to influence democratic outcomes. This incident highlighted the vulnerabilities of digital democracy to foreign interference and the urgent need for robust strategies to combat online manipulation.

The ongoing challenge for e-democracy is to harness the immense potential of digital tools for engagement and mobilization while simultaneously safeguarding against the corrosive effects of misinformation and malicious AI-generated content.

Digital Democracy and the Digital Divide

While digital technology undeniably offers unparalleled opportunities for political engagement, it also exacerbates existing societal inequalities through the digital divide. The Obama campaign’s successful embrace of technology allowed it to connect with a younger, tech-savvy demographic. Still, it also inadvertently highlighted the exclusion of those without reliable internet access or digital literacy. Matthew Hindman’s question in The Myth of Digital Democracy, “Is the Internet making politics less exclusive?” remains highly pertinent. The answer continues to be a complex mix of “yes” and “no.” While the internet possesses immense power to inform, mobilize, and empower many citizens, it simultaneously creates a barrier for poorer citizens and marginalized communities who lack the necessary digital access or skills.

Despite the overwhelming success of digitally-driven campaigns, the responsibility remains for politicians, campaigns, and policymakers to acknowledge and actively address the digital divide, ensuring that the promise of digital democracy extends to all segments of the population, fostering true inclusivity in the democratic process.

The Echo Chamber Effect: Navigating Political Rumors in the Digital Age

Political discourse in the digital age, while offering unprecedented reach for candidates, simultaneously presents a fertile ground for the propagation of rumors and misinformation that can significantly impact, if not derail, a politician’s career. The rapid dissemination capabilities of the internet, through social media platforms, blogs, and mass email campaigns, mean that claims, regardless of their veracity, can spread virally within minutes. Websites like Snopes.com have become crucial in the ongoing effort to verify or debunk urban legends and internet rumors, maintaining extensive sections dedicated to political falsehoods. Historically, Snopes documented numerous debunked rumors surrounding prominent figures like Barack Obama, addressing claims about his U.S. citizenship, alleged attempts to ban recreational fishing, and even his purported refusal to sign Eagle Scout certificates. These examples underscore a long-standing pattern of online disinformation targeting public figures.

The persuasive power of these online rumors is often amplified by manipulated visual content, thanks to advancements in image and video editing software. What began with rudimentary photo manipulation using tools like Adobe Photoshop has evolved into a far more sophisticated and concerning phenomenon: deepfakes. These AI-generated synthetic media can convincingly depict individuals saying or doing things they never did, blurring the lines between reality and fabrication. For instance, in recent election cycles, deepfakes have been used to generate fabricated audio of political candidates urging voters to stay home or to create realistic but entirely false videos of public figures making controversial statements. This makes it more challenging than ever for the average media consumer to discern truth from deception.

The proliferation of online political rumors and misinformation has profound implications for modern democratic practices. Beyond individual smear campaigns, these falsehoods contribute to a broader erosion of trust in institutions, the media, and even the electoral process itself. The 2016 US presidential election offers a stark historical example of how foreign state actors, notably Russia, leveraged social media and disinformation to sow discord and influence public opinion, highlighting the vulnerability of digital platforms to coordinated online interference. More recently, in the lead-up to and during elections across the globe, we’ve seen a surge in sophisticated AI-driven misinformation campaigns. These efforts often exploit existing societal divisions, amplify conspiracy theories, and create an “echo chamber effect” where individuals are primarily exposed to information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs, making it harder for accurate information to penetrate.

Conspiracy theories, which thrive on the internet’s interconnected nature, further complicate the landscape. From QAnon, which has influenced real-world political events and even acts of violence, to various unfounded claims about election integrity, these theories can mobilize segments of the population based on entirely false narratives. The rapid virality of such content on platforms like TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), and even niche forums means that fact-checking efforts often struggle to keep pace with the speed of dissemination.

In this environment, the onus is increasingly on savvy media consumers to be vigilant and employ critical thinking skills. This involves actively seeking out legitimate and diverse sources of information, cross-referencing claims, and being skeptical of emotionally charged or sensational content. Fact-checking organizations like Snopes, PolitiFact, and FactCheck.org play an indispensable role, but individual media literacy is paramount. Furthermore, social media platforms are under growing pressure to implement more robust content moderation policies. However, balancing free speech with the need to combat harmful misinformation remains a complex and contentious challenge. Ultimately, while the internet empowers political engagement, it also demands a heightened awareness of the disinformation ecosystem that can undermine the very foundations of digital democracy.