15.7 Media Influence on Laws and Government

The media, with its enduring voice and role in shaping public opinion, has consistently been a powerful force in politics. From the earliest days of newspapers and pamphlets during the American Revolution, where figures like Samuel Adams used the Boston Gazette to galvanize anti-British sentiment, political discourse found a critical platform. The emergence of broadcast media in the 20th century, with its radio briefs and television reports, further amplified political stories, bringing them directly into the homes of the public.

Beyond acting as a watchdog, the media provides citizens with news coverage of issues and events, and also offers public forums for debate. Consequently, media support—or the lack thereof—can significantly influence public opinion and governmental action. A notable modern example occurred in 2007, when The Washington Post conducted a four-month investigation into the substandard medical treatment of wounded soldiers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. The ensuing two-part feature exposed deplorable conditions and systemic bureaucratic failures. This media scrutiny led directly to the resignation of the Secretary of the Army and the two-star general in charge of the medical facility, demonstrating the media’s capacity to hold powerful institutions accountable.

Nevertheless, the media’s role in politics remains a subject of ongoing debate. Many observers question the driving forces behind certain stories and the extent of media influence. As William James Willis, author of The Media Effect: How the News Influences Politics and Government, notes:

Sometimes the media appear willing or unwitting participants in chasing stories that the government wants them to pursue; other times, politicians find themselves chasing issues that the media has exaggerated through its coverage. Over the decades, political scientists, journalists, politicians, and political pundits have presented numerous arguments regarding the media’s influence on government and politicians (Willis, 2007).

Regardless of the initiator, media coverage of politics invariably sparks questions among the public. Despite regulations such as the now largely defunct Fairness Doctrine (which aimed to ensure balanced coverage) and Section 315 of the Communications Act (requiring equal airtime for political candidates), a significant portion of the public remains skeptical of the media’s role in shaping political opinion. More recent surveys reflect this continued distrust. For instance, a 2024 Gallup poll indicated that only 31% of Americans trust the mass media a “great deal” or “fair amount,” a figure that has steadily declined over decades and marks one of the lowest points in over five decades. This skepticism is particularly pronounced among Republicans, with 88% expressing low trust in the media in 2024, while nearly half of Democrats (46%) also report low trust. These statistics underscore the perceived political influence of the media and the delicate balance it must maintain when addressing political issues, especially in an era of heightened political polarization.

Politics, Broadcast Media, and the Internet

Throughout their respective histories, radio, television, and the internet have played essential and evolving roles in politics. As technology developed, citizens began demanding greater levels of information and analysis from media outlets and, in turn, from politicians. This section examines the evolution of politics in the context of media development.

Radio

Radio, as a medium, offered the ability to broadcast up-to-the-minute breaking news for the first time. On November 2, 1920, KDKA in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, became the first station to broadcast election results from the Harding-Cox presidential race, effectively pioneering a brand new technology that fundamentally changed how timely information was disseminated (American History). This development greatly impacted newspaper publishers who, until then, had stood as exclusive stewards of timely information, but now found radio able to transmit news and information directly into American living rooms. The public responded positively, eager for more immediate involvement in U.S. politics.

As radio technology developed, Americans demanded greater participation in the political and cultural debates shaping their democratic republic (Jenkins). Radio provided a way to hold these debates in a public forum; it also offered a venue for politicians to speak directly to the public, a phenomenon that could not have occurred on such a large scale before its invention. This dynamic profoundly changed politics, as candidates and elected officials suddenly had to communicate their messages effectively to a large, unseen audience (ThinkQuest). Famous examples include Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “fireside chats” during the Great Depression and World War II, which directly addressed the American public, building trust and explaining complex policies in an accessible manner. These broadcasts brought politicians into people’s homes, necessitating that many learn effective public speaking tailored for radio.

Television

Today, television remains a significant source of political news for many Americans, a relationship that dates back almost to the medium’s inception. Political candidates began using TV commercials to speak directly to the public as early as 1952. Sometimes referred to as “living room candidates,” they understood the power of the television screen and the importance of reaching viewers at home. In 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower became one of the first candidates to harness television’s popularity. Madison Avenue advertising executive Rosser Reeves convinced him that short ads played during popular TV programs like I Love Lucy would reach more voters than any other form of advertising. This innovation had a permanent effect on the way presidential campaigns are run, ushering in an era where carefully crafted televised appearances and advertising became central to political strategy (Living Room Candidate).

Nixon–Kennedy Debates of 1960

The relationship between politics and television took a massive step forward in 1960 with a series of four televised “Great Debates” between presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. An estimated 70 million U.S. viewers tuned in to the first of these on September 26, 1960. The debates gave voters their first chance to see the candidates’ debate, marking television’s definitive entry into the world of politics.

Just as radio changed the way politicians thought about their speeches, television emphasized the importance of their appearance. Shortly before the first debate, Nixon had spent two weeks in the hospital with a knee injury. By the day of the discussion, he had lost weight and appeared pale. In addition, he wore an ill-fitting shirt and refused to wear makeup. Kennedy, however, looked fit, tan, and confident. The visual difference between the two candidates was stark to audiences; Kennedy appeared much more presidential. Indeed, those who watched the first broadcast essentially declared that Kennedy had won it, while those who listened on the radio often felt Nixon had prevailed on substance. A record number of viewers watched the debates, and many historians have attributed Kennedy’s narrow success at the polls that November, in part, to the public perception of the candidates formed during these televised encounters (Mary Ferrell Foundation).

War and Television

Later in the decade, rising U.S. involvement in Vietnam brought television and public affairs together again in a significant way. For the first time on a large scale, networks brought the horrors of battle directly into U.S. homes. Although television’s invention predated the Korean War, the medium was in its infancy during that conflict, and its audience and technology were still too limited to play a significant role (Museum of Broadcast Communications). As such, in 1965, the Vietnam War became the first “living-room war.”

Early in the war, the coverage often seemed mostly upbeat:

It typically began with a battlefield roundup, written from wire reports based on the daily press briefing in Saigon, read by the anchor and illustrated with a battle map. A policy story from Washington would usually follow the battlefield roundup, and then a film report from the field…. As with most television news, the emphasis was on the visual and, above all, the personal: “American boys in action” was the story, and reports emphasized their bravery and skill in handling the technology of war (Museum of Broadcast Communications).

However, in 1969, television coverage began to shift as journalists grew increasingly skeptical of the government’s claims of progress, and stories placed greater emphasis on the human costs of war (Museum of Broadcast Communications). While explicit gore typically remained off-screen, a few significant violent moments profoundly shook the country upon their broadcast. In 1965, CBS aired footage of U.S. Marines setting village huts on fire, and in 1972, NBC audiences witnessed Vietnamese civilians fall victim to a napalm strike. Such scenes altered America’s perspective of the war, significantly contributing to the burgeoning antiwar sentiment.

Political News Programming and the 24/7 Cycle

Television news has undergone dramatic changes over the medium’s history. For years, nightly news broadcasts dominated the political news cycle; then, round-the-clock cable news channels appeared. CNN debuted in 1980, with its founder, Ted Turner, famously stating, “We won’t be signing off until the world ends. We’ll be on, and we will cover the end of the world, live, and that will be our last event…and when the end of the world comes, we’ll play ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’ before we sign off (TV Tropes).”

The rise of 24-hour news stations, such as CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC, has fundamentally reshaped the political landscape. These networks increased competition for viewership, leading to the targeting of specific demographics and the creation of shows appealing to particular political preferences. This intensified competition often fuels sensationalism and partisanship, as networks may filter out stories that do not support their political ideals, a practice known as “gatekeeping,” or engage in “issue framing” to reinforce political messages. For example, critics argue that networks on both the left and right selectively highlight or downplay certain aspects of stories to align with their editorial stance, contributing to a more polarized public.

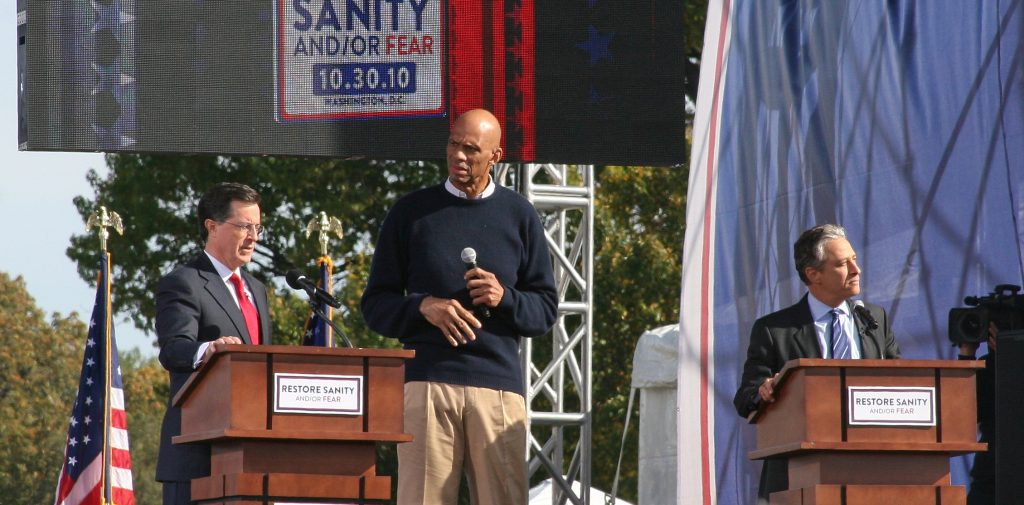

In response to the pervasive nature of cable news, nightly network news programs have often changed their focus to emphasize more local stories or delve deeper into narratives that major national news programs might overlook. Additionally, the increasing popularity and influence of satirical news shows such as The Daily Show and Last Week Tonight, along with late-night talk show monologues on programs like The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and “A Closer Look” on Late Night with Seth Meyers, have attracted younger generations to engage with politics. These comedic news programs have, in recent years, become prominent cultural arbiters and watchdogs of political issues, leveraging the outspoken nature of their hosts and their frank, often humorous, coverage of political topics to critique power and disseminate information.

Satire’s Serious Sway: John Oliver’s Unconventional Influence on Policy

John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight, a satirical news program on HBO, has carved out a unique and often impactful niche in the media landscape. While ostensibly a comedy show, its meticulously researched deep dives into complex, usually overlooked, systemic issues have frequently transcended mere entertainment, sparking public discourse, influencing policy debates, and in some documented cases, contributing to tangible changes in laws and governmental practices. The show’s influence has even been dubbed the “John Oliver Effect” by some media outlets, a term Oliver himself often playfully dismisses.

The show’s methodology is key to its influence. Each episode typically features one extensive segment dedicated to a single topic, ranging from net neutrality and predatory municipal fines to SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) suits and the bail system. Unlike traditional news segments that might offer a brief overview, Last Week Tonight delves into the historical context, legal intricacies, and real-world consequences of these issues, often presenting them with compelling visuals, expert interviews, and Oliver’s signature blend of outrage and humor. This comprehensive yet accessible approach allows the show to educate a broad audience on subjects that might otherwise be considered too dry or complex for mainstream attention.

One of the most widely cited examples of the “John Oliver Effect” is its impact on net neutrality. In a June 2014 segment, Oliver passionately urged viewers to submit comments to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regarding its proposed changes to net neutrality rules. He explained the technical jargon understandably, framing the issue as a critical fight for the future of the internet. The segment’s call to action was so compelling that it reportedly crashed the FCC’s website due to an unprecedented surge in public comments. This massive public outcry is widely credited with playing a significant role in the FCC’s decision in 2015 to reclassify broadband internet as a public utility under Title II of the Communications Act, an important victory for net neutrality advocates. While the rules were later repealed, Oliver revisited the topic in 2017, again prompting a flood of public comments and demonstrating the show’s continued ability to mobilize its audience on regulatory matters.

Beyond federal policy, Last Week Tonight has also influenced discussions at the state and local levels. For instance, a segment on municipal fines and court fees highlighted how these penalties disproportionately affect low-income communities, often leading to a cycle of debt and incarceration for minor infractions. The show’s exposure of these practices, particularly in places like Ferguson, Missouri, contributed to increased public awareness and pressure on municipalities to reform their revenue-generating legal systems. Similarly, segments on the predatory practices of the bail bond industry have shed light on how the cash bail system disadvantages poor people, prompting renewed calls for bail reform across various jurisdictions.

The show’s willingness to directly challenge powerful entities has also had an impact. Its coverage of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP) suits, which are often filed to silence critics through costly litigation, brought significant attention to this legal tactic. Oliver himself faced a SLAPP suit from coal magnate Robert Murray, which he ultimately won. His subsequent segment on the issue not only detailed his own experience but also educated viewers on how these lawsuits suppress free speech, advocating for stronger anti-SLAPP laws. While direct legislative changes are often slow and multifaceted, the show’s ability to expose such practices undoubtedly raises public and legislative scrutiny.

While it is difficult to quantify the precise causal link between a comedy show and legislative outcomes, Last Week Tonight undeniably serves as a powerful agenda-setter. By dedicating significant airtime to issues often ignored by traditional news, it elevates their importance in the public consciousness, forcing politicians and policymakers to confront them. Its unique blend of investigative journalism and comedic delivery makes complex issues digestible and engaging, empowering a segment of the public to become more informed and, at times, to take action, thereby indirectly but significantly influencing the trajectory of laws and government.

Online News and Politics

Ultimately, the internet has become a progressively significant influence on how Americans access political information. Websites such as The Huffington Post, The Daily Beast, and The Drudge Report (though the latter’s influence has waned compared to its peak) continue to break news stories and offer political commentary. However, the online news landscape has diversified exponentially since 2010. News consumption has shifted dramatically towards digital platforms, with social media playing a particularly dominant role.

Social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram have become primary conduits for political news and discussion, often bypassing traditional media gatekeepers. This allows politicians to communicate directly with constituents, as seen in President Donald Trump’s prolific use of Twitter to announce policies, criticize opponents, and rally his base. However, this direct access also facilitates the rapid spread of misinformation and disinformation. The virality of social media means that unverified claims or deliberately false narratives can reach millions before traditional fact-checking mechanisms can respond. For instance, during election cycles, social media is often awash with misleading memes, out-of-context clips, and fabricated stories designed to influence voter perception.

The growth of far-right sites like InfoWars, founded by Alex Jones, exemplifies a darker side of online news. InfoWars has consistently promoted conspiracy theories, such as the false claim that the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting was a hoax, leading to immense suffering for victims’ families and significant legal repercussions for Jones. These sites often operate with minimal journalistic standards, thriving on sensationalism and distrust of mainstream institutions, and their content can be amplified across social media, reaching audiences who may be receptive to their narratives. This phenomenon contributes to the fragmentation of public discourse and the rise of “echo chambers,” where individuals are primarily exposed to information that confirms their existing beliefs, making it harder to establish shared facts or engage in constructive political debate.

The 2020 and 2024 presidential debates between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, and the 2024 debate between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, offer modern examples of the media’s profound influence. While traditional networks broadcast these events, their post-debate analysis and commentary heavily shaped public perception. For instance, the first Biden-Trump debate in June 2024 generated intense media scrutiny over Biden’s performance, leading to widespread discussion about his age and fitness for office. This media narrative significantly impacted public opinion and contributed to subsequent political developments. Conversely, following the Harris-Trump debate in September 2024, media coverage focused mainly on Harris’s strong performance and the fact-checking of Trump’s claims by the moderators, influencing perceptions of both candidates. These events demonstrate how media framing, punditry, and real-time fact-checking (or lack thereof, depending on the outlet) can instantly color public understanding of political contests.