16.6 Mass Media, New Technology, and the Public

The introduction of groundbreaking technologies often sparks a fascinating societal phenomenon: the process of adoption and diffusion. When Apple launched the iPad in April 2010, designer Josh Klenert’s sentiment that the device was “ridiculously expensive” yet still compelling enough to pre-order and queue for exemplifies the behavior of an early adopter. This characteristic, observed in technologically enthusiastic pioneers, marks the initial phase of what sociologists call the technology adoption life cycle. Understanding this cycle helps explain why some individuals eagerly embrace innovations while others remain resistant, and the subsequent benefits and challenges each group presents.

The concept of the technology adoption life cycle has its roots in rural sociology studies from the 1950s. Researchers like George Beal, Joe Bohlen, and Everett Rogers at the University of Iowa meticulously observed the rate at which farmers adopted hybrid seed corn. Their findings revealed a consistent pattern: an initial slow uptake, followed by a period of rapid adoption, and finally a leveling off. They noted that personal and social characteristics significantly influenced this process; younger, more educated farmers tended to be early adopters, while older, less educated farmers often waited until the technology was widely accepted or resisted it altogether.

Diffusion of Technology: The Technology Adoption Life Cycle

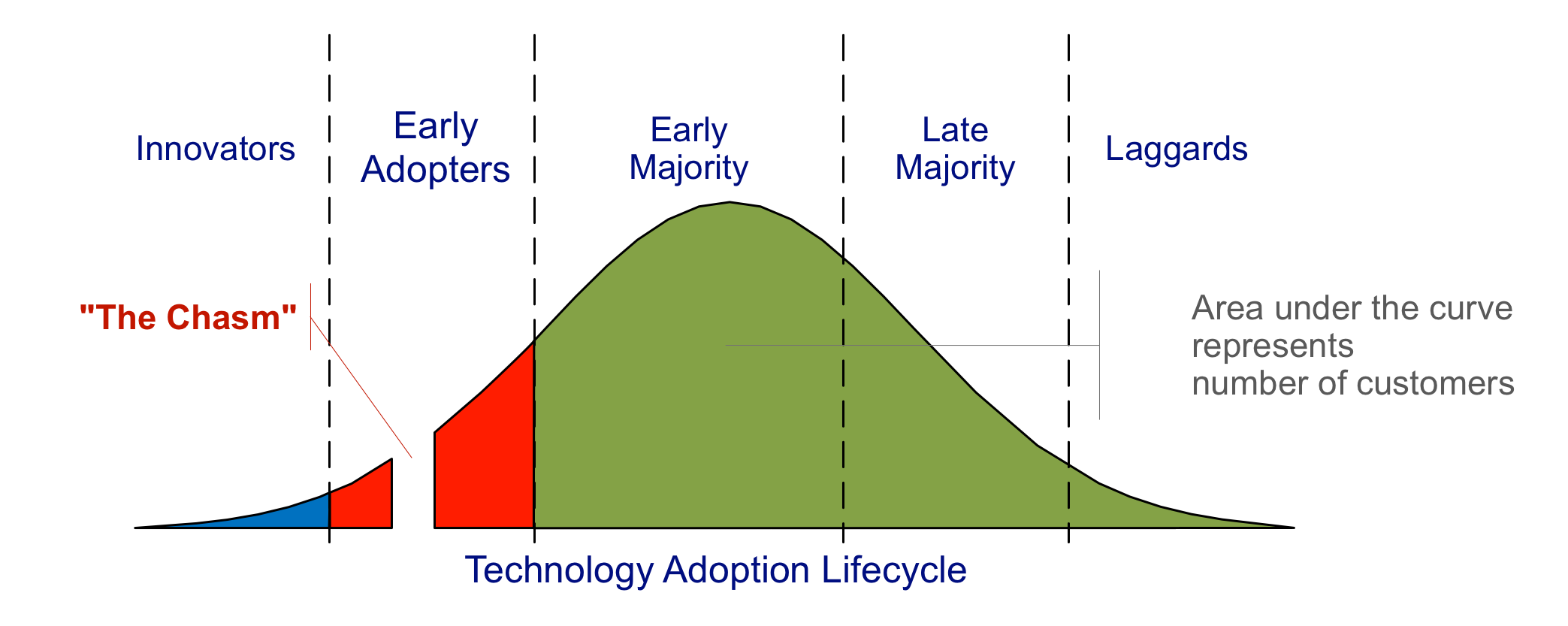

In 1962, Rogers expanded these findings into a generalized model in his seminal book, Diffusion of Innovations, applying the principles observed in farming to the broader spread of new ideas and technologies. Rogers categorized participants into five distinct groups:

- Innovators: These are the pioneers, often characterized by their adventurous spirit and willingness to experiment with new technology for its own sake. They are typically risk-takers who embrace novelties even before their practical applications are fully understood.

- Early Adopters: Like Josh Klenert and early enthusiasts of the iPad, these individuals are technically sophisticated and quick to recognize the potential of new technology to solve professional or personal problems. Crucially, they serve as opinion leaders, influencing the broader adoption of an innovation.

- Early Majority: This group constitutes the first segment of the mainstream market. They are pragmatic and wait for innovations to be proven and refined before adopting them, bringing new technology into widespread, everyday use.

- Late Majority: These individuals are more skeptical and cautious, adopting new technology only after it has been widely accepted and is perceived as essential or a standard. They may express reservations about its benefits initially.

- Laggards: This group is the most resistant to change, often adhering to traditional methods and criticizing the use of new technology by others. They adopt innovations only when essential, if at all (Rogers, 1995).

Successful new technologies typically follow this adoption curve. Innovators and early adopters, driven by the novelty and potential, often acquire innovations immediately, often without being deterred by high initial prices. For instance, the original iPad’s launch in April 2010 saw Apple sell 300,000 units on its first day and over 1 million within a month, far exceeding industry expectations (Goldman, 2010). These early segments of the market largely fueled this initial surge. However, the broader mainstream consumers, comprising the early majority, tend to wait, observing market trends, price reductions, and refinements before making a purchase.

Modern examples of technologies transitioning through these stages are abundant. Laptops, MP3 players, and digital cameras, once the domain of early adopters, have long become mainstream commodities. More recently, technologies like smart home devices, virtual reality headsets, and wearable fitness trackers have traversed from niche early adoption to increasing mainstream penetration. By the time technology reaches the early and late majority, manufacturers have typically refined the product, made it more user-friendly, and reduced its cost. For example, the price of e-readers like Amazon’s Kindle saw significant reductions in the years following its initial launch as competition increased and production scaled (Bartash, 2010). This market dynamic often leads to greater accessibility and widespread adoption.

Despite widespread technological progress, some individuals and demographics remain resistant to adopting new technologies. The example of John Uribe, who in 2008 continued to use an outdated Netscape web browser and dial-up internet even after support ceased, illustrates the laggard mentality. “It’s kind of irrational,” Mr. Uribe said. “It worked for me, so I stuck with it. Until there is some reason to abandon it, I won’t (Helft, 2008).” His preference for familiar, albeit obsolete, technology highlights a segment of the population that prioritizes consistency over innovation. Data from various census bureaus and digital access reports consistently show that while broadband internet access is pervasive, significant portions of populations, particularly in older demographics or lower-income households, may still lack high-speed internet or choose not to adopt it, citing a lack of interest or perceived need.

However, far from hindering technological progress, these “laggards” play a crucial role in pacing and shaping development. As technology forecaster Paul Saffo suggests, they provide a critical “pull” by demanding that innovations prove their utility and reliability. If only early adopters dictated the market, the technology landscape might be filled with fleeting fads that lack widespread practical application. The coexistence of early adopter and laggard characteristics within individuals is also common; for instance, someone might embrace the latest smartphone but only utilize a fraction of its advanced features, effectively being a laggard in terms of feature adoption. This inherent push-and-pull helps ensure that only truly valuable and robust technologies achieve long-term mainstream success.

From Hype to Halted: Decoding the Downfall of Digital Dreams

Not every technological innovation destined for market shelves achieves widespread consumer adoption. While some products soar, others falter, becoming cautionary tales of concepts that were either ahead of their time, fundamentally flawed, or failed to resonate with the public. These “technological flops” serve as critical reminders that innovation, no matter how ambitious, is subject to the unpredictable forces of consumer demand, market timing, and user experience.

One such historical example is the Apple Newton, first introduced in 1993 as the MessagePad. This personal digital assistant (PDA) featured capabilities remarkably similar to modern smartphones, including personal information management (contacts, calendars), note-taking, and even rudimentary email functions, with add-on storage slots for expansion. Despite Apple’s characteristic clever advertising and significant promotional efforts, the Newton never achieved the iconic status of most Apple products. Its bulky size, particularly when compared to later, more successful PDAs like the PalmPilot, and its prohibitive cost (ranging from around $700 to $1,000 for advanced models) were significant barriers. Perhaps most famously, its handwriting recognition software, while pioneering, was often inconsistent, becoming the target of ridicule by late-night talk show comedians and cartoonists. Production of the Newton ceased in 1998, yet its groundbreaking concepts undeniably paved the way for the smaller, more affordable, and widely popular PalmPilot, and in turn, influenced the design and functionality of virtually every mobile internet device that followed.

Another notable misstep from the late 1990s was DIVX, an initiative by electronics retailer Circuit City (which itself later faced bankruptcy). DIVX aimed to revolutionize video rental by offering movies on disposable discs that customers could keep and watch for two days. Users could then choose to discard, recycle, or pay a continuation fee for extended viewing, or an additional fee to convert it into a “DIVX silver” disc for unlimited playback. Launched in 1998, DIVX was promoted as a convenient alternative to traditional video rental, promising no returns or late fees. However, its introduction unfortunately coincided with the burgeoning popularity of DVD technology. Consumers, still wary from the earlier Betamax versus VHS format war, were reluctant to invest in yet another proprietary format, especially one that offered less flexibility than DVD. By 1999, just a year after its launch, DIVX was largely obsolete, costing Circuit City an estimated $114 million and leaving early adopters with unusable equipment, though a partial refund was offered (Mokey, 2009).

The mid-1990s also saw the ill-fated Microsoft Bob, an attempt by Microsoft to simplify the graphical user interface for non-technical users. Launched in 1995, Microsoft Bob presented a cartoon-like interface resembling rooms in a house, where users could click on objects (e.g., a pen for word processing) to navigate their desktop operations. Its logo, a yellow smiley face, aimed for an approachable image. Despite a significant advertising campaign, Bob proved to be a catastrophic failure. Its high price, demanding hardware requirements for the era, and often annoying user experience alienated potential customers. Its irrelevance was cemented later the same year with the launch of Windows 95, which featured a significantly more intuitive and user-friendly Windows Explorer interface that required far less “simplification.”

These historical examples—Apple Newton, DIVX, and Microsoft Bob—demonstrate a consistent pattern: technological innovations, no matter how visionary, can stumble due to factors like cost, user experience, market timing, or competing standards. They highlight the wisdom of the “late majority” and “laggard” adopters, who benefit from allowing early adopters to “beta test” the technology, waiting until products are more refined, user-friendly, and often, more affordable.

The landscape of technological failures continues to evolve, demonstrating that even industry giants can miscalculate consumer demand or market readiness.

One prominent recent example is Google Stadia, a cloud gaming service launched in 2019. Despite Google’s vast technological resources and infrastructure, Stadia struggled to gain traction. It promised the ability to stream high-quality games without expensive hardware. Still, it faced challenges with game library size, perceived input lag for some users, and a confusing business model that required purchasing games even if you subscribed to the service. Ultimately, Google announced the shutdown of Stadia in 2023, refunding users for hardware and game purchases, a costly lesson in the highly competitive and technically demanding cloud gaming market.

Another notable modern misstep is the rapid decline of Quibi, a short-form mobile video streaming service launched in 2020. Despite attracting nearly $1.75 billion in funding and featuring content from major Hollywood creators, Quibi failed to find an audience. Its core premise—premium, short-form video content designed specifically for mobile viewing, with unique “Turnstyle” technology allowing seamless switching between portrait and landscape modes—didn’t resonate. Observers pointed to its subscription model in a crowded streaming market, the timing of its launch during a pandemic when people were essentially at home watching on larger screens, and its lack of social sharing features as key reasons for its demise. Quibi shut down just six months after its launch.

Even within established product lines, missteps occur. While generally successful, Meta’s metaverse strategy has faced significant headwinds. Mark Zuckerberg’s ambitious pivot to building the metaverse, including the rebranding of Facebook to Meta, involved massive investments in virtual reality hardware (Meta Quest headsets) and metaverse platforms like Horizon Worlds. While VR headset sales have grown, Horizon Worlds has struggled with user engagement, graphical fidelity, and perceived lack of compelling experiences, drawing criticism for being clunky and unappealing. Billions of dollars have been poured into this vision. While Meta continues to invest, the widespread consumer adoption and profitability remain elusive, prompting questions about the long-term viability and mainstream appeal of its current metaverse iteration. This contrasts sharply with Meta’s earlier successes, such as the acquisition and integration of Instagram and WhatsApp.

These recent examples, from cloud gaming to short-form video and ambitious metaverse visions, reinforce the enduring truth that technological innovation, while essential, carries inherent risks. Success hinges not just on technological prowess but equally on understanding nuanced consumer behavior, market dynamics, and delivering a compelling value proposition that truly resonates with the broad public.

Mass Media Outlets and New Technology

As new technologies penetrate the mainstream, mass media outlets are in a perpetual state of adaptation. The initial success of the iPad, selling millions of units within months of its launch, spurred a rapid response from traditional media. Newspapers like The New York Times and USA Today, along with major magazines and television networks, rushed to develop dedicated applications for the tablet, recognizing it as a crucial new platform for content delivery. These early apps showcased the iPad’s capabilities beyond static text, incorporating interactive features like multimedia content (video and audio), dynamic layouts, and integrated puzzles, leveraging the tablet’s touch interface. The New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. highlighted this shift, stating their iPad app aimed to “take full advantage of the evolving capabilities offered by the Internet” while maintaining their traditional role as a trusted information filter (Brett, 2010).

The media’s adaptation also involved overcoming technical hurdles. Apple’s decision to exclude Adobe Flash from its mobile ecosystem, which was then dominant for online video, forced many traditional TV networks to convert their video content to HTML5. This enabled seamless streaming of full TV episodes on devices like the iPad. Early movers like CBS and Disney quickly offered free content via the iPad’s web browser, while others, like ABC, launched dedicated apps. Beyond transforming existing content, new technologies even facilitated the revival of dormant media forms; in 2010, Condé Nast famously resurrected Gourmet magazine as an iPad-exclusive application, Gourmet Live, demonstrating how new platforms could breathe new life into legacy brands.

Today, this continuous adaptation by mass media is even more pronounced. Streaming services have supplanted traditional linear television, with platforms like Netflix, Disney+, Max, and Peacock investing billions in original content and competing for subscriber attention across a multitude of devices, from smart TVs to smartphones. News organizations now prioritize digital-first strategies, breaking news on their websites, social media, and dedicated apps, often incorporating live blogs, interactive graphics, and user-generated content. Podcasts, a form of audio media, have experienced a massive resurgence, with major media companies and independent creators alike producing vast libraries of on-demand audio content, accessible through apps like Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts.

Furthermore, the integration of AI is becoming critical for media outlets. AI is used for personalized content recommendations (e.g., Netflix’s algorithm), automated news summaries, transcription services for podcasts and videos, and even generating localized news stories or sports reports. Media companies are also exploring immersive technologies like virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) for enhanced storytelling. However, these are still mainly in the early adopter phase for mass consumption. The convergence of new technologies, particularly AI and ubiquitous connectivity, ensures that the relationship between mass media and the public remains in a constant state of evolution, continually reshaping how information is created, distributed, and consumed.

New Technology for Early Adopters: The Era of AI

A significant evolution for today’s early adopters is the rapid emergence and integration of artificial intelligence (AI) across various domains. While early adoption was once defined by devices like personal computers, the internet, or smartphones, the current frontier for tech-savvy pioneers is increasingly centered around AI-powered applications and tools.

Early adopters in the 2020s are engaging with sophisticated AI models for creative work, productivity, and exploration. This includes experimenting with generative AI tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and DALL-E, Google’s Gemini, or Midjourney, which can generate human-like text, create realistic images from text prompts, or even compose music. These innovators are exploring the capabilities of AI in content creation, coding assistance (e.g., GitHub Copilot), data analysis, and scientific research. They are often the first to integrate AI assistants into their workflows, automate complex tasks using AI, and push the boundaries of what these technologies can achieve. Their adoption drives the refinement of AI models, identifies new use cases, and surfaces ethical considerations, much like early internet users shaped the web’s development. This early engagement is crucial for identifying real-world applications and addressing the challenges of AI development.