2.3 Media Effects Theories

Early media studies focused on the use of mass media in propaganda and persuasion. However, journalists and researchers soon turned to the behavioral sciences to help understand the impact of mass media and communication on society. Scholars have developed various approaches and theories to understand and study the mechanisms of communication.

Media messages can impact their audience members in many ways. At the most superficial level, the media can inspire short-term learning of information, although this highly depends on the motivation of the person engaging with the media content. Media messages could also inspire several other effects. Based on the content it displays, it may also encourage audience members to develop feelings about a product, individual, or idea (advertisers have found it far easier to get people to form new opinions rather than change existing ones). In some instances, media can inspire a behavioral or psychological response. Refer to the theories presented in this chapter when researching communication and consider the various ways media messages can influence culture.

The widespread fear that mass-media messages could outweigh other stabilizing cultural influences, such as family and community, led to the development of the direct effects model in media studies. This model assumed that audiences passively accepted media messages and would exhibit predictable reactions in response to those messages. For example, following the 1938 radio broadcast of “War of the Worlds,” which depicted a fictional news report of an alien invasion, some listeners panicked when they perceived the story as accurate.

Challenges to the Direct Effects Theory

The results of the People’s Choice Study challenged this model. Conducted in 1940, the study aimed to assess the impact of political campaigns on voter decisions. Researchers found that voters who consumed the most media had generally already decided for which candidate to vote. In contrast, undecided voters typically turned to family and community members for help in making their decision. The study thus discredited the direct effects model and influenced a host of other media theories (Hanson, 2009). These theories do not necessarily give an all-encompassing picture of media effects but rather work to illuminate a particular aspect of media influence.

Marshall McLuhan’s Influence on Media Studies

During the early 1960s, English professor Marshall McLuhan wrote two books that had a profound impact on the history of media studies. Published in 1962 and 1964, respectively, the Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media both traced the history of media technology. They illustrated how these innovations had changed both individual behavior and the broader culture. Understanding Media introduced a phrase that McLuhan has become known for: “The medium is the message.” This notion represented a novel take on attitudes toward media, in which the media of dissemination itself became instrumental in shaping human and cultural experiences.

His bold statements about media garnered McLuhan a great deal of attention, as both his supporters and critics responded to his utopian views on how media could transform 20th-century life. McLuhan spoke of a media-inspired “global village” at a time when Cold War paranoia reigned and the Vietnam War sparked heated debates. Although 1960s-era utopians received these statements positively, social realists found them cause for scorn. Despite—or perhaps because of—these controversies, McLuhan became a pop culture icon, mentioned frequently in the television sketch-comedy program Laugh-In and appearing as himself in Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall.

The Internet and its accompanying cultural revolution have made McLuhan’s bold utopian visions seem like prophecies. Indeed, his work has garnered considerable attention in recent years. Analysis of McLuhan’s work has, interestingly, remained relatively unchanged since the publication of his works. His supporters point to the hopes and achievements of digital technology and the utopian state that such innovations promise. The current critique of McLuhan, however, reveals the state of modern media studies. The field has evolved since McLuhan published his work in the 1960s, and many contemporary scholars criticize his lack of a methodology and theoretical framework for the ideas he espoused.

Despite his lack of scholarly diligence, McLuhan had a profound influence on media studies. Professors at Fordham University have formed an association of scholars influenced by McLuhan. McLuhan’s other significant achievement lies in popularizing the concept of media studies. His work introduced the idea of media effects to the public arena and established a new perspective for the public to consider the impact of media on culture (Stille, 2000).

Agenda-Setting Theory

In contrast to the extreme views of the direct effects model, the agenda-setting theory of media states that mass media determine the issues that concern the public rather than the public’s views. Under this theory, the problems that receive the most attention from the press become the issues that the public discusses, debates, and advocates. This means that the media determines what issues and stories the public contemplates. Therefore, when the media fails to address a particular problem, it becomes marginalized (or unknown) in the public’s mind (Hanson).

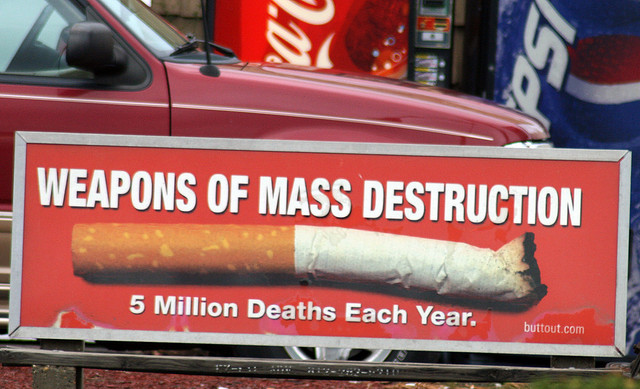

When critics claim that a particular media outlet has an agenda, they draw on this theory. Agendas can range from a perceived liberal bias in the news media to the propagation of cutthroat capitalist ethics in films. For example, the agenda-setting theory explains such phenomena as the rise of public opinion against smoking. Before the mass media began taking an antismoking stance, most people perceived smoking as a personal health issue. By promoting antismoking sentiments through advertisements, public relations campaigns, and a variety of media outlets, the mass media moved smoking into the public arena, making it a public health issue rather than a personal health issue (Dearing & Rogers, 1996). Sometimes, coverage of natural disasters dominates the news cycle. However, as news coverage wanes, so does the general public’s interest.

Media scholars who specialize in agenda-setting research study the salience, or relative importance, of an issue and then attempt to understand the factors that contribute to its importance. The relative salience of an issue determines its position within the public agenda, which in turn influences the creation of public policy. Agenda-setting research traces public policy from its roots as an agenda through its promotion in the mass media and finally to its final form as a law or policy (Dearing & Rogers, 1996).

Uses and Gratifications Theory

Practitioners of the uses and gratifications theory study how the public consumes media. This theory posits that consumers utilize the media to fulfill specific needs or desires. For example, an individual may enjoy watching a show like Bridgerton while simultaneously tweeting about it on X (formerly Twitter) with friends. Many people use the Internet to seek entertainment, find information, communicate with like-minded individuals, or pursue self-expression. Each of these uses gratifies a particular need, and the needs determine how each person uses the media. By examining the media choices of different groups, researchers can determine the motivations behind media use (Papacharissi, 2009).

A typical uses and gratifications study explores the motives for media consumption and the consequences associated with using that media. In the case of Bridgerton and X, the individual above uses the Internet as a way to find entertainment and to connect with friends. Researchers have identified several common motives for media consumption. These include relaxation, social interaction, entertainment, arousal, escape, and a host of interpersonal and social needs. By examining the motives behind the consumption of a particular form of media, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of both the reasons for that medium’s popularity and the roles it fills in society. A study of the motives behind a given user’s interaction with Facebook, for example, could explain the role Facebook takes in society and the reasons for its appeal.

Uses and gratifications theories of media are often applied to contemporary media issues. The analysis of the relationship between media and violence discussed in the preceding sections exemplifies this. Researchers employed the uses and gratifications theory, in this case, to reveal a nuanced set of circumstances surrounding violent media consumption, as individuals with aggressive tendencies often find themselves drawn to violent media (Papacharissi, 2009).

Symbolic Interactionism

Another commonly used media theory, symbolic interactionism, states that individuals derive and develop their sense of self through human interaction. This means that the way individuals act toward someone or something is based on the meaning they have for that person or thing. To effectively communicate, people use symbols with shared cultural meanings. People can construct symbols from just about anything, including material goods, education, or even the way people talk. Consequently, these symbols play a crucial role in the development of the self.

This theory helps media researchers better understand the field because of the important role the media plays in creating and propagating shared symbols. Due to the media’s power, it can construct symbols independently. By applying symbolic interactionist theory, researchers can examine how media affect a society’s shared symbols and, in turn, the influence of those symbols on the individual (Jansson-Boyd, 2010).

One way the media creates and utilizes cultural symbols to influence an individual’s sense of self is through advertising. Advertisers strive to imbue certain products with a shared cultural meaning, making them more desirable. For example, ownership of luxury automobiles signifies membership in a particular socioeconomic class. Technology company Apple has employed advertising and public relations to establish itself as a symbol of innovation and nonconformity. Using an Apple product, therefore, may garner a symbolic meaning and send a particular message about the product’s owner.

Media also propagate other noncommercial symbols. National and state flags, religious images, and celebrities gain shared symbolic meanings through their representation in the media.

Spiral of Silence

The spiral of silence theory, which posits that individuals who hold minority opinions tend to silence themselves to avoid social isolation, explains the role of mass media in shaping and perpetuating dominant opinions. As those who hold minority opinions self-silence, the illusion of consensus grows, and so does social pressure to adopt the dominant position. This creates a self-propagating loop in which minority voices are marginalized, and perceived popular opinion largely aligns with the majority opinion. For example, before and during World War II, many Germans opposed Adolf Hitler and his policies; however, they kept their opposition silent out of fear of isolation and stigma.

Because the media serves as one of the most important gauges of public opinion, scholars often use this theory to explain the interaction between media and public opinion. According to the spiral of silence theory, if the press propagates a particular opinion, it will effectively silence opposing opinions through an illusion of consensus. This theory is particularly relevant to public polling and its application in the media (Papacharissi).

Media Logic

The media logic theory states that standard media formats and styles serve as a means of perceiving the world. Today, the deep-rootedness of media in cultural consciousness means that media consumers need only engage with a particular television program for a few moments to understand its format, whether it is a news show, a comedy, or a reality show. The pervasiveness of these formats means that American culture utilizes the style and content of these shows as a means to interpret reality. For example, think about a TV news program that frequently shows heated debates between opposing sides on public policy issues. This style of debate has become a template for handling disagreement for those who consistently watch this type of program.

Media logic affects both institutions and individuals. The modern televangelist has evolved from the adoption of television-style promotion by religious figures. At the same time, the increasing use of television in political campaigns has led candidates to consider their physical appearance as an essential part of their campaign (Altheide & Snow, 1991).

Cultivation Analysis

The cultivation analysis theory posits that prolonged exposure to media leads individuals to develop an illusory perception of reality, based on the most repetitive and consistent messages of a particular medium. This theory most commonly applies to analyses of television due to that medium’s uniquely pervasive and repetitive nature. Under this theory, someone who watches a great deal of television may form a distorted picture of reality that does not accurately reflect actual life. Televised violent acts, whether those reported on news programs or portrayed on television dramas, for example, greatly outnumber violent acts that most people encounter in their daily lives. Thus, an individual who watches a lot of television may view the world as more violent and dangerous than crime statistics suggest.

Cultivation analysis projects encompass various research areas, including the differences in perception between heavy and light media users. To apply this theory, the media content that an individual normally watches must undergo analysis for various types of messages. Then, researchers must consider the given media consumer’s cultural background to correctly determine other factors that could influence an individual’s perception of reality. For example, the socially stabilizing influences of family and peer groups influence children’s television viewing and the way they process media messages. Suppose an individual’s family or social circle plays a significant role in their life. In that case, the social messages they receive from these groups may compete with the messages they receive from television.

Functional Analysis

Functional analysis can be traced back to the fields of sociology and anthropology. It examines how different parts of society (or in this case, the media) contribute to the overall stability and functioning of the whole. In mass communication, this perspective focuses on the functions that media serve for individuals, groups, and society as a whole. Harold Lasswell famously outlined three key tasks: surveillance (providing information about the environment), correlation (interpreting and connecting information), and transmission (passing on social norms and values). Charles Wright later added a fourth: entertainment.

Functional analysis considers both manifest functions and latent functions. For example, a manifest (intended and obvious) function of news media is to inform the public. A latent (unintended and often hidden) function might reinforce existing social hierarchies by giving more voice to specific groups. This perspective also acknowledges dysfunctions, which provoke negative consequences. Media can spread misinformation, create moral panics, or contribute to social fragmentation.

Functional analysis provides a macro-level perspective on the media’s role in society, highlighting its contributions to social order and stability, as well as its potential for disruption.

Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura’s social learning theory posits that people learn behaviors by observing others, particularly through media. This theory challenges the notion that learning occurs only through direct experience. In mass communication, social learning theory suggests that media portrayals of behaviors, especially those conducted by attractive or high-status models, can influence viewers to adopt those behaviors (Bandura, 1977).

Key concepts include:

- Observational learning: A person can learn something by watching others engage in a particular action.

- Modeling: The person then imitates the observed behaviors.

- Vicarious reinforcement: The person observes the consequences of imitating this behavior and adjusts their behavior accordingly.

Social learning theory advocates often research the impact of violent media content. Studies have shown that exposure to violent media can increase aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, especially in children. However, the theory also applies to positive behaviors. Media can promote prosocial behaviors, such as cooperation and empathy, by showcasing positive role models.

Social learning theory emphasizes the significant impact of media on behavior, underscoring the importance of producing responsible media content.

Frame Theory

Frame theory suggests that how the media presents information (or how they “frame” it) influences how audiences understand and interpret it. Frames indicate mental structures that shape perceptions of reality by selectively highlighting certain aspects of a situation and rendering them more salient (Entman, 1993). In mass communication, media use frames to shape public opinion and discourse.

The media can create frames through various techniques, including:

- Selection: Choosing which information to include or exclude.

- Emphasis: Highlighting certain aspects of a story.

- Presentation: Using specific language, images, and other cues.

For example, a media outlet can frame a news story about immigration as a national security threat (emphasizing potential risks) or as a humanitarian crisis (emphasizing the plight of refugees). These different frames can lead to vastly different public perceptions and policy preferences. Think about the difference between the following phrases:

- Tax cuts or tax relief

- Drilling for oil or exploring for energy

- Gay marriage or same-sex marriage

- Undocumented workers or illegal immigrants

- Terrorists or rebels

Shanto Iyengar demonstrated the power of how one word could influence the audience’s perception of an issue by citing a scenario created by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky about the outbreak of a disease expected to kill 600 people and two programs that could combat the disease. One group received information that the adoption of Program A would save 200 people. In contrast, Program B offered a one-third probability of saving 600 people and a two-thirds probability of saving no one. They told a second group that 400 people would die with the adoption of Program A, and that Program B promised a one-third probability that no one would die and a two-thirds probability that all 600 people would die.

Even though both groups received the same information, the group that heard the scenario framed with the word “save” voted for Program A 72% of the time, whereas the group that listened to the scenario framed with the word “dies” chose Program B 78% of the time (Iyengar, 1991).

Frame theory emphasizes the active role of media in shaping public discourse and understanding. It highlights the importance of critically analyzing media messages to understand how they are being framed and what potential biases they might contain.