2.5 Media Studies Controversies

Essential debates over media theory have questioned the foundations and, hence, the results of media research. Within academia, theories and research can represent an individual’s life’s work and livelihood. As a result, issues of tenure and position, rather than issues of truth and objectivity, can sometimes fuel discussion over theories and research.

Problems With Methodology and Theory

Although the use of advanced methodologies can resolve many of the questions raised about various theories, the use of these theories in public debate generally follows a broader understanding. For example, if a hypothetical study found that convicted violent offenders had aggressive feelings after playing the video game Overwatch, many would take this as proof that video games cause violent acts without considering other possible explanations. Often, the nuances of these studies get lost when they enter the public arena.

Active versus Passive Audience

Media studies theorists remain divided over the question of whether audiences act passively or actively when receiving mass media messages. A passive audience, in the most extreme statement of this position, passively accepts the messages that the media sends it. An active audience, on the other hand, is fully aware of the complexity of media messages and makes informed decisions about how to process and interact with them. Newer trends in media studies have sought to develop a more nuanced view of media audiences than the active versus passive debate allows. Still, in the public sphere, this opposition often frames many debates about media influence (Heath & Bryant, 2000).

Arguments against Agenda-Setting Theory

Many criticisms have been leveled at agenda-setting theory, primarily that studies dedicated to the theory cannot prove cause and effect; essentially, no one has yet shown that the media agenda sets the public agenda, rather than the other way around. An agenda-setting study could examine the correlation between the prevalence of a topic in the media and subsequent changes in public policy. It may conclude that the media sets this agenda. However, policymakers and lobbyists often conduct public relations efforts to encourage the creation of specific policies. In addition, public concern over issues generates media coverage, making it difficult to determine whether the media is responding to the public’s desire for coverage of an issue or if it is pushing an issue onto its agenda (Kwansah-Aidoo, 2005).

Arguments Against Uses and Gratifications Theory

The general presuppositions of the uses and gratifications theory have been subject to criticism. By assuming that media fulfill a functional purpose in an individual’s life, the uses and gratifications theory implicitly justifies and reaffirms the place of media in the public sphere. Furthermore, because it focuses on the personal and psychological aspects of media, the theory cannot question whether media artificially imposes itself on an individual. Studies involving the uses and gratifications theory often include sound methodology, but the overall assumptions of the studies remain unquestioned (Grossberg et al., 2006).

Arguments Against the Spiral of Silence Theory

Although many regard the spiral of silence theory as useful when applying its broadest principles, it appears weaker when dealing with specifics. For example, the phenomenon of the spiral of silence is most visible in individuals who fear social isolation. Those who are less fearful of such isolation are less likely to stay silent if public opinion turns against them. Nonconformists contradict the claims of the spiral of silence theory.

Critics have also pointed out that the spiral of silence theory relies heavily on the values of various cultural groups. A public opinion trend in favor of gun control may not silence the consensus within National Rifle Association meetings. Every individual considers themself a part of a larger social group with specific values. Although these values may differ from widespread public opinion, individuals need not fear social isolation within their particular social group (Gastil, 2008).

Arguments Against Cultivation Analysis Theory

Critics have faulted cultivation analysis theory for relying too heavily on a broad definition of violence. Detractors argue that because violence means different things to different subgroups and individuals, any claim that an entire audience would unanimously characterize acts of violence in the same way is false. This critique would necessarily extend to other studies involving cultivation analysis. Different people interpret media messages in varying ways, so making broad claims can lead to problems. Cultivation analysis remains an essential component of media studies, but critics have questioned its unqualified validity as a theory (Shanahan & Morgan, 1999).

Politics and Media Studies

Media theories and studies afford a variety of perspectives. When proponents of a particular view employ those theories and studies, however, they often make oversimplified claims, which can result in contradictions. When politicians and others employ media studies to validate a political perspective, this usually happens.

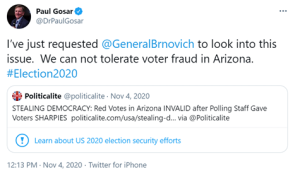

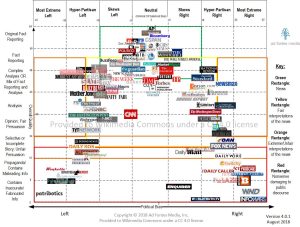

Media Bias

Media can influence political opinion through their coverage, sparking debate over media bias. A 1985 study found that journalists had a greater likelihood of holding liberal views than the general public. Over the years, many have cited this study to support the opinion that the media holds a liberal bias. However, another study found that between the years 1948 and 1990, Republican candidates received 78 percent of newspaper presidential endorsements (Hanson).

Media favoritism again became a source of contention during the 2024 presidential race. A survey conducted in October 2024 found that over one-third of respondents believed news media coverage was unfairly biased in favor of Kamala Harris, while 15% felt it was prejudiced in favor of Donald Trump (YouGov, 2024). Allegations that the media favored Harris seemed to bolster the idea of a liberal bias, a popular opinion in conservative circles. However, other studies suggest that favorable media coverage often follows a candidate’s rise in public opinion, indicating that the media may react to public sentiment rather than attempting to influence it. Obama’s 2008 election showed that favorable media coverage of him occurred only after his poll numbers rose, hinting that the media reacted to public opinion rather than attempting to influence it (Reuters, 2008).

Media Decency

Decency standards in media continue to change in unpredictable ways. Once banned in the United States for obscenity, scholars now consider James Joyce’s Ulysses a classic of modern literature. In contrast, many schools have banned the children’s classic, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for its use of ethnic slurs. The regulatory power that the government possesses over the media keeps decency an inherently political issue. As media studies have progressed, they have increasingly become part of the debates over decency standards. Although media studies cannot prove a word or image is indecent, they can help discern the impact of that word or image and, thus, greatly influence the debate.

Organizations or figures with stated goals often use media studies to support those aims. For example, the Parents Television Council reported on a study that compared the ratio of comments about nonmarital sex to comments about marital sex during the hours of 8 p.m. to 9 p.m. The study employed content analysis to come up with specific figures; however, the Parents Television Council then used those findings to make broad statements, such as “the institution of marriage is regularly mocked and denigrated (Rayworth, 2008).” Because content analysis does not examine the effect on audiences or analyze how the media presents the material, it does not provide a scientific basis for judging whether a comment mocks and denigrates marriage; therefore, the research does not support such interpretations. For example, researchers performing a content analysis by documenting the amount of sex or violence on television do not analyze how the audience interprets the content. They note the number of instances portrayed in the sample. Equally, partisan groups can employ various linguistic strategies to tailor media studies to their agenda.

Media studies involving violence, pornography, and profanity often draw the interest of some who have also conducted their own media studies. In 2001, for example, a Senate bill aimed at Internet decency, which had little support in Congress, came to the floor. One of the sponsoring senators attempted to increase interest by bringing a file full of some of the most egregious pornographic images he could find to the Senate floor. The bill passed 84 to 16 (Elmer-Dewitt, 2001).

Weaponizing Research: The Misuse of Media Studies in Public Debate

The misuse of media studies to bolster pre-existing agendas is a pervasive issue, often obscuring genuine understanding of media’s cultural impact. Pundits, social reformers, and politicians frequently cherry-pick or misinterpret research findings to support their narratives, regardless of the study’s actual conclusions or limitations (Boyle, 2022).

This practice is particularly problematic given the public’s ongoing struggle to grasp the complex effects of evolving media technologies. For instance, debates surrounding the influence of video games on aggression often exemplify this misuse of the term. Following tragic events involving violence, pundits may cite studies suggesting a link between violent video games and aggression, even when the research is correlational rather than causal or when the effect sizes are small. This selective use of research creates a moral panic, diverting attention from other potential contributing factors like mental health or access to firearms.

For instance, former lawyer Jack Thompson said in an interview with CBS News that “hundreds of studies” existed that proved the link between violent video games and real violence. Later in the interview, he listed increasing school murder statistics as proof of the effects of violent video games (Vitka, 2005). In light of the media effects theories elucidated in this chapter, Thompson fabricated the findings of video game–violence research and made claims that no media effects scholar could confidently make. Thompson’s frivolous use of the legal system to initiate lawsuits against the Grand Theft Auto video game developer, Take-Two Interactive, led to the state of Alabama revoking his license to practice law in 2005. In 2008, the Florida Supreme Court disbarred him for life (Hefflinger, 2008).

Similarly, politicians might cite studies on social media echo chambers to justify stricter content moderation policies, ignoring research that suggests the effects of these echo chambers are often overstated or that such policies could stifle free speech. Social reformers, while usually well-intentioned, can also fall prey to this, citing studies that support their desired social changes without fully acknowledging the complexities or nuances revealed in the research.

This selective application of research not only undermines the integrity of media studies but also hinders productive public discourse on the genuine impact of media on culture. Instead of fostering informed debate, it creates a climate where research is weaponized to support predetermined conclusions.

Media Consolidation

Although this book will discuss media consolidation in more depth in later chapters, the topic’s intersection with media studies results deserves mention here. Media consolidation occurs when large media companies buy up smaller media outlets. Although government regulation has historically stymied this trend by prohibiting ownership of a large number of media outlets, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has loosened many of the restrictions on large media companies since the 1980s.

Media studies often prove vital to decisions regarding media consolidation. These studies measure the impact that consolidation has had on the media’s public role and on the content of local media outlets, comparing it with that of conglomerate-owned outlets. The findings often vary depending on the group conducting the study. Sometimes the FCC chooses to ignore these findings.

In 2003, the FCC loosened restrictions on owning multiple media outlets in the same city, citing studies that the agency had developed to assess the influence of specific media outlets, such as newspapers and television stations (Ahrens, 2003). In 2006, however, reports surfaced that the agency had discarded a key study during the 2003 decision. The study demonstrated an increase in time allocated for news when TV stations were owned locally, thus raising questions about whether media consolidation provided a benefit for local news (MSNBC, 2006).