3.2 History of Books

Ancient Books

While spoken language has existed in some form for over 50,000 years, the invention of writing occurred more than 5,500 years ago in Mesopotamia and has taken many forms since its inception. Sumerians would press cuneiform marks into wet clay tablets, foreshadowing the power to preserve stories and information for generations. That being said, it would take several centuries before anyone, except highly educated scribes, could create or decipher the various forms of written communication that would evolve from cuneiform marks. These forms included pictographs, which usually resembled the concepts they attempted to depict, and ideographs, which used an abstract symbol to represent an object or idea. The complexity of such systems meant that scribes held significant influence and power until the invention of the alphabet. This far simpler system, which used letters to represent individual sounds, developed between 1700 BC and 1500 BC.

Most historians trace the origins of the book back to the ancient Egyptians, whose papyrus scrolls bore a distinct resemblance to modern books. From the time they first developed a written script, around 3000 BCE, the Egyptians wrote on various surfaces, including metal, leather, clay, stone, and bone. Most prominent, though, was their practice of using reed pens to write on papyrus scrolls. In many ways, papyrus was an ideal material for the Egyptians. They could make it using the tall reeds that grew plentifully in the Nile Valley. They either glued or sewed papyrus sheets together to make scrolls. A standard scroll measured around 30 feet long and 7 to 10 inches wide, while the longest Egyptian scroll ever found stretched more than 133 feet, making it almost as long as the Statue of Liberty from end to end (Harry Ransom Center).

By the sixth century BCE, papyrus served as the most common writing surface throughout the Mediterranean. It was used by the Greeks and Romans (with Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey among the oldest surviving written works). Because papyrus grew in Egypt, the Egyptians had a virtual monopoly over the papyrus trade. Many ancient civilizations housed their scrolls in large libraries, which acted as both repositories of knowledge and displays of political and economic power. Powerful entities in the ancient world grew tired of the Egyptians’ monopoly over the papyrus trade and sought other methods to record information on a physical medium.

Made from treated animal skins scraped thin to create a flexible, even surface, parchment had several advantages over papyrus: it had more durability, could feature writing on both sides of the sheet, and Egypt did not monopolize its production. Its spread coincided with another crucial development in the history of the book. Between the second and fourth centuries, the Romans began sewing folded sheets of papyrus or parchment together and binding them between wooden covers. This form, known as the codex, has essentially the same structure as modern books. The codex provided a much more user-friendly experience than the papyrus scroll. Written records became more portable, easier to store and handle, and less expensive to produce. It also allowed readers to quickly flip between sections. Reading a scroll required two hands, while readers could open a codex in front of themselves, which permitted note-taking. Traditions changed slowly in the ancient world, however, and the scroll remained the dominant form for secular works for several centuries. The codex became the preferred form for transmitting early Christian texts, and the spread of Christianity eventually led to the dominance of the codex; by the 6th century CE, it had almost entirely replaced the scroll.

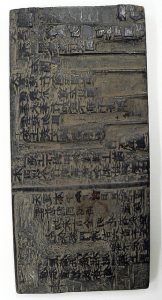

The next major innovation in the history of books, the use of block printing on paper, began in Tang Dynasty China around 700 CE, though it wouldn’t arrive in Europe for nearly 800 years. The first known examples of text printed on paper appeared in tiny, 2.5-inch-wide scrolls of Buddhist prayers commissioned by Japan’s Empress Shōtoku in 764 CE. The Buddhist text Diamond Sutra (868 CE) represents the earliest example of a dated, printed book. Woodblock printers had to meticulously carve an entire page of text onto a wooden block, then ink and press the block to print a page. The complexity of the Chinese and Korean ideographs meant this form of printing did not provide a practical means for achieving mass communication.

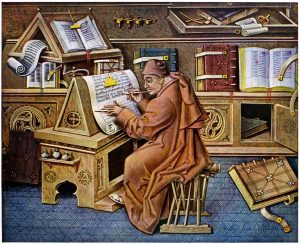

In medieval Europe, however, scribes still laboriously copied texts by hand. Monasteries dominated book culture in the Middle Ages, which made them centers of intellectual life. Many of the classical texts still in existence owe their preservation to diligent medieval monks, who regarded scholarship, including the study of secular and pre–Christian writers, as a means to draw closer to God. These hand-copied illuminated manuscripts included painted embellishments added to complement the handwritten books. The word “illuminate” comes from the Latin “illuminare,” which means to light up, and monks designed some medieval books to shine through the application of gold or silver decorations. Other ornate additions included illustrations, decorative capital letters, and intricately drawn borders. The degree of embellishment depended on the book’s intended use and the wealth of its owner. The aristocracy valued medieval manuscripts so highly that some scribes placed so-called book curses at the front of their manuscripts, warning that anyone who stole or defaced the copy would face ill fortune. A copy of the Vulgate Bible, for example, warned: “Whoever steals this book let him die the death; let be him be frizzled in a pan; may the falling sickness rage within him; may he be broken on the wheel and be hanged (Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries).”

Though illuminated books were highly prized, they were also expensive and labor-intensive to create. By the end of the Middle Ages, the papal library in Avignon, France, held only a few thousand manuscripts, compared to the nearly half a million texts found at the Library of Alexandria in ancient times (Fischer, 2004). Bookmaking in the Western world became less expensive when paper emerged as the primary writing surface. Making paper from rags and other fibers, a technique that originated in China during the second century, reached the Islamic world in the eighth century and led to a flourishing of book culture in the region. By the 12th century, accounts claim that Marrakesh, in modern-day Morocco, had a street lined with a hundred book sellers. It would take another two centuries before paper manufacturing began in earnest in Europe.

Gutenberg’s Industry-Changing Invention

Papermaking coincided with another crucial step forward in the history of books: Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of mechanical movable type in 1448. The Biography Channel and A&E both named Gutenberg as the single most influential person of the second millennium, ahead of Shakespeare, Galileo, and Columbus. Time magazine cited movable type as the single most important invention of the past 1,000 years. Through his invention, Gutenberg indisputably changed the world.

Much of Gutenberg’s life remains shrouded in mystery. He lived as a German goldsmith and book printer. He spent the 1440s collecting investors for a mysterious project —an invention that combined existing technologies, such as the screw press, already a valuable tool for papermaking, with his innovation: individual metal letters and punctuation marks that he could independently rearrange. This process would revolutionize the book production industry. Though Gutenberg probably printed other, earlier materials, the Bible he printed in 1455 brought him great renown. In his small print shop in his hometown of Mainz, Germany, Gutenberg used his movable type press to print 180 copies of the Bible, 135 on paper and 45 on vellum (Harry Ransom Center). This book, commonly known as the Gutenberg Bible, ushered in Europe’s so-called Gutenberg Revolution and paved the way for the commercial mass production of books. In 1978, the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin purchased a complete copy of the Gutenberg Bible for $2.2 million.

Over the next few centuries, the printing press transformed nearly every aspect of books: their production, distribution, and composition all underwent significant changes. Printing provided a much swifter system for producing books than handwriting did, and paper’s low cost made it a preferred medium to parchment. Before the printing press, patrons would commission the production of a book, and monks would begin the process of copying the text. The printing press enabled printers to create multiple identical editions of the same book in a relatively short time. Meanwhile, it probably would’ve taken a scribe at least a year to handwrite a single Bible. As Gutenberg’s invention led to the proliferation of printing shops across Europe, the very concept of what a book looked like also began to evolve. In medieval times, the scarcity of books made them valuable and rare since they resulted from hundreds (if not thousands) of hours of work. After Gutenberg, books became standardized, plentiful, and relatively cheap to produce and disseminate (which had a profound impact on language). Early publishers attempted to replicate the appearance of illuminated manuscripts in their printed books, complete with hand-drawn decorations. However, they soon realized the economic potential of producing multiple identical copies of a single text, and book printing soon became a speculative business, with printers trying to estimate how many copies a particular book would sell. By the end of the 15th century, 50 years after Gutenberg’s invention of movable type, printing shops had sprung up throughout Europe, with an estimated 300 in Germany alone. Gutenberg’s invention proved a resounding success, and the printing and selling of books boomed. The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center estimates that, before the invention of the printing press, the total number of books in all of Europe was approximately 30,000. By 1500 CE, the number of books in Europe had grown to approximately 10 to 12 million (Jones, 2000). Early printers faced the challenge of crafting all the characters of a typeface in a particular size and style, or font, to create any printed message, although they would be able to purchase mass-produced type by the 1600s.

Effects of the Mass Production of Books

The advent of the printed book revolutionized the post–Gutenberg world. As the world around it changed, the form of the book itself did not undergo substantial changes. Despite minor tweaks and alterations, the ancient form of the codex remained relatively intact. What changed? The production and distribution of books revolutionized the way information circulated throughout the world.

Simply put, the mechanical reproduction of books meant that more books became available at a lower cost, and the growth of international trade allowed these books to have a wider reach. The desire for knowledge among the growing middle class, combined with the newfound availability of classical texts from ancient Greece and Rome, helped fuel the Renaissance, a period marked by a celebration of the individual and a shift toward humanism. For the first time, the barrier to dispersing texts disappeared, allowing political, intellectual, religious, and cultural ideas to spread widely. In addition, many people could read the same books and be exposed to the same ideas simultaneously, giving rise to mass media and mass culture. The concept of individual learning evolved as the written word enabled new ideas to permeate previously closed communities. Published writing revolutionized the scientific disciplines. For example, standardized, widely dispersed texts meant that scientists in Italy had exposure to the theories and discoveries of scientists in England. Due to improved communication, technological and intellectual ideas spread more quickly, allowing scientists from diverse fields to build upon the breakthroughs and successes of others more easily.

As the Renaissance progressed, the size of the middle class expanded, along with literacy rates. Rather than a few hundred precious volumes housed in monasteries or university libraries, book availability to people outside these settings increased substantially, which meant women had increased exposure to written texts for the first time in many societies. In effect, the mass production of books helped to democratize knowledge. However, this spread of information didn’t proceed without resistance. Thanks in part to the spread of dissenting ideas, the Roman Catholic Church, the dominant institution of medieval Europe, found its control slipping. In 1487, only a few decades after Gutenberg first printed his Bible, Pope Innocent VIII insisted that church authorities prescreen all books before publication (Green & Karolides, 2005). Ironically, the church banned the Bible if the publisher printed it in any language other than Latin—a language that few people outside of clerical or scholarly circles understood. In 1517, Martin Luther instigated the Protestant Reformation. He challenged the church’s authority by insisting that people had the right to read the Bible in their language. The church rightly feared the spread of vernacular Bibles; the more people who had access to the text, the less control the church could exert over how it was interpreted. Since the church’s interpretation of the Bible, in no small part, dictated the way many people lived their lives, the church’s sway over the hearts and minds of the faithful became severely undermined by accessible printed Bibles and the wave of Protestantism they encouraged. The Catholic Church’s attempt to control the printing industry proved impossible to maintain. Over the next few centuries, the church would see its power decline significantly, as it no longer served as the sole keeper of religious knowledge as it had throughout the Middle Ages.

This instance with the Bible illustrates a trend during the infancy of publishing. The Renaissance saw a growing interest in texts published in the vernacular, the speech of the “common people.” As books became more accessible to the middle class, people began to read books written in their native language. Early well-known works in the vernacular included Dante’s Divine Comedy (first printed in Italian in 1472) and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (published in Middle English in the 15th century). Genres with widespread appeal, such as plays and poetry, gained increasing popularity. In the 16th and 17th centuries, inexpensive chapbooks (the name derives, appropriately enough, from the term “cheap books”) became popular. The proliferation of chapbooks showed just how much the Gutenberg Revolution had transformed the written word. In just a few hundred years, many people had access to reading material, and books lost their status as sacred objects.

Due to the high value placed on human knowledge during the Renaissance, libraries experienced significant growth during this period. Much like their ancient Egyptian counterparts, libraries once again served as institutions that could display national power and wealth. The German State Library in Berlin was founded in 1661, and other European centers soon followed, such as the National Library of Spain in Madrid (established in 1711) and the British Library (the world’s largest) in London (established in 1759). Universities, clubs, and museums also started constructing libraries; however, the public often did not have access to these resources. The United Kingdom’s Public Libraries Act of 1850 fostered the development of free, public lending libraries. After the American Civil War, public libraries flourished in the newly reunified United States, thanks in part to fundraising and lobbying efforts by women’s clubs. Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie helped bring Renaissance ideals of artistic patronage and democratized knowledge into the 20th century by establishing more than 1,680 public libraries between 1881 and 1919 (Krasner-Khait, 2001).

History of Document Control

While Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press ushered in an age of democratized knowledge and incipient mass culture, it also transformed the act of authorship, making writing a potentially profitable enterprise. Before the mass production of books, authorship had few financial rewards unless a generous patron got involved. As a consequence, pre-Renaissance texts were often collaborative, and many books didn’t even list an author. The earliest concept of copyright, derived from the scriptoria era, dictated who had the right to copy a book by hand. The printed book, however, offered the potential for a speculative commercial enterprise, because businesses could now sell large numbers of identical copies. The explosive growth of the European printing industry meant that authors could potentially profit from the books they wrote if an agency recognized their legal rights. In contemporary terms, copyright grants a person the exclusive right to prevent others from copying, distributing, or selling a work. The creator of a work usually exercises this right, though they have the right to sell or transfer the copyright. Works not covered by copyright or for which the copyright has expired become part of the public domain, which means anyone in the public may freely use the content without seeking permission or making royalty payments.

The origins of contemporary copyright law usually trace back to the Statute of Queen Anne. This law, enacted in England in 1710, first recognized the legal rights of authors, though in an incomplete manner. It granted a book’s publisher 14 years of exclusive rights and legal protection, renewable for another 14-year term if the author still lived. Anyone who infringed on a copyrighted work paid a fine, half of which went to the author and half to the government. Early copyright law aimed to limit monopolistic practices and censorship opportunities, provide stability to authors, and promote learning by ensuring the accessibility of documents to a broad audience.

The United States established its first copyright law not long after the Declaration of Independence. The U.S. Constitution granted Congress the power “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries” in Article I, Section 8, Clause 8. The first federal copyright law, the Copyright Law of 1790, modeled its exclusive rights clause on the Statute of Queen Anne by granting exclusive rights to creators for 14 years, at which point the author could renew those rights for another 14 more if they still lived at the first term’s conclusion.

The “limited times” mentioned in the Constitution have steadily increased in duration since the 18th century. The Copyright Act of 1909 allowed for an initial 28-year term of copyright, which permitted one additional 28-year renewal term. The Copyright Act of 1976, which preempted the 1909 act, extended copyright protection to “a term consisting of the life of the author and 50 years after the author’s death,” a period substantially longer than the original law’s potential 56-year term. In 1998, the government extended the copyright law to 70 years after the author’s death. The 1998 law, called the Copyright Term Extension Act, also added a 20-year extension to all currently copyrighted works. This automatic extension meant that no new works would enter the public domain until 2019 at the earliest. Critics of the Copyright Term Extension Act referred to it as the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act” because the Walt Disney Company had lobbied for the law (Krasniewicz, 2010). Due to the 20-year copyright extension, Mickey Mouse and other Disney characters remained out of the public domain, meaning they were still the exclusive property of Disney. This changed in 2022 when Winnie the Pooh and other titles entered the public domain, followed by the Steamboat Willie version of Mickey Mouse in 2024. It did not take long before horror films, toilet paper companies, and satirical news programs started integrating the once-commercial icons into public discourse.

The 1976 law also codified the terms of fair use for the first time. Fair-use law specifies the ways someone other than the copyright holder may legally use a work (or parts of a work) under copyright. Using content for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” A book review quoting snippets of a book or a researcher citing someone else’s work does not constitute copyright infringement. Given an Internet culture that thrives on remixes, linking, and other creative uses of source material, the boundaries of the legal definition of fair use have presented numerous challenges in recent years. As such, nonprofit organizations like Creative Commons offer copyright licenses that allow creators to share their work publicly while providing flexibility on how their work can be used, distributed, and modified by others.

History of the Book-Publishing Industry

Except for self-published works, the author does not take charge of producing the book or distributing it to the world. These days, the tasks of editing, designing, printing, promoting, and distributing a book generally fall to the book’s publisher. Although authors usually have their names prominently displayed on the spine, a published book results from the product of many different kinds of labor by many other people.

Early book printers often acted as publishers, as they produced pages and sold them commercially. In England, the Stationers’ Company, which essentially operated as a printer’s guild, had a monopoly over the printing industry and maintained the authority to censor texts. The Statute of Queen Anne, the 1710 copyright law, was partially a result of some early publishers overstepping their bounds.

In the 19th-century United States, the Northeast emerged as the nation’s publishing epicenter, with hotspots in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. During the 1800s, the U.S. book industry experienced rapid expansion. In 1820, the books manufactured and sold in the United States totaled approximately $2.5 million; by 1850, despite a substantial drop in book prices, sales figures had quintupled (Howe, 2007). Technological advances in the 19th century, including the development of machine-made paper and the Linotype typesetting machine, simplified and increased the profitability of book publishing. Many of today’s large publishing companies originated in the 19th century; for example, Houghton Mifflin was founded in 1832, Little, Brown & Company was formed in 1837, and Macmillan debuted in Scotland in 1843, opening its U.S. branch in 1869. By the turn of the century, New York became the epicenter of publishing in the United States.

The rapid growth of the publishing industry and evolving intellectual property laws meant that authors could make money from their writing during this period. Not surprisingly, the first literary agents also emerged in the late 19th century. Literary agents act as intermediaries between the author and the publisher, negotiating contracts and parsing difficult legal language. The world’s first literary agent, A. P. Watt, worked in London in 1881 and essentially defined the role of the contemporary literary agent—he got paid to negotiate on behalf of the author. A former advertising agent, Watt decided to charge based on commission, meaning that he would take in a set percentage of his client’s earnings. Watt set his fee as 10 percent, the standard rate today.

Paperback books gained immense popularity in the first half of the 20th century. Books covered in less expensive, less durable paper existed since Renaissance chapbooks, but they usually featured crude printed works meant only as passing entertainment. In 1935, the publishing industry underwent a significant transformation when Penguin Books Ltd., a paperback publisher, launched in England, ushering in the so-called paperback revolution. Instead of being crude and cheaply made, Penguin titles were simple but well-designed. Though Penguin sold paperbacks for only 25¢, they avoided crude material and concentrated on providing works of literary merit, thus fundamentally changing the idea of how to present quality reading material. Some early Penguin titles included Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man. In the decades that followed, more and more people launched paperback publishing companies hoping to capitalize on Penguin’s success. The first U.S.-based paperback company, Pocket Books, started in 1939. By 1960, paperback books outsold hardbacks in the United States (Ogle, 2003).

Publishing underwent significant changes in the second half of the 20th century, marked by the consolidation of the U.S. book-publishing industry, which mirrored the broader trend toward media consolidation. Between 1960 and 1989, approximately 578 mergers and acquisitions took place in the U.S. book industry; between 1990 and 1995, 300 occurred; and between 1996 and 2000, nearly 380 occurred (Greco, 2005). This represents a part of the larger international trend toward media consolidation, where large international media empires have acquired smaller companies across various industries. For example, the German media company Bertelsmann AG acquired Random House and merged it with Penguin in 2013 to form Penguin Random House. London-based Pearson PLC, formerly the owner of Penguin, is now part of Penguin Random House following its merger with Random House. The AOL Time Warner merger, which included Warner Books, led to Warner Books being rebranded and eventually acquired by Hachette Book Group. Little, Brown and Company, also part of Time Warner, is now under Hachette Book Group as well. Because publicly traded companies have obligations to their shareholders, the publishing industry found itself under pressure to generate increasingly high profits. By 2022, roughly 60-70 percent of all books sold in the United States were published by the five large publishing houses, often referred to as the Big Five: Penguin Random House (owned by Bertelsmann), HarperCollins (owned by News Corp), Simon & Schuster (owned by Paramount Global), Hachette, and Macmillian (Crumm, 2022). In the early years of the 21st century, book publishing was an increasingly centralized, profit-driven industry.