3.5 Current Publishing Trends

The last few decades have seen a sharp rise in electronic entertainment. The rise of digital platforms and the increasing diversity of media content have led to a more fragmented media consumption landscape. Video game and digital entertainment consumption have continued their upward trend. As of 2023, time spent playing video games or using a computer for leisure averaged 34 minutes a day across all age groups, beating out reading by four minutes a day (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). In a world full of entertainment options, each clamoring for people’s time, the publishing industry means to do everything it can to capture readers’ attention.

Amazon dominates the industry

Amazon’s rise to dominance in the book industry is a story of strategic innovation, relentless customer focus, and a willingness to disrupt traditional models. It’s a journey that began with humble origins and evolved into a behemoth that reshaped how books are bought, sold, and even read.

Jeff Bezos founded Amazon in 1994 as an online bookstore that operated out of his garage. The early internet was like the Wild West, and Bezos saw an opportunity to leverage the nascent technology to offer a wider selection of books than any physical store could hold. Amazon focused on providing people with convenience and choice. Customers could browse a vast catalog from the comfort of their own homes and have books delivered to their doorstep. Amazon designed features like personalized recommendations, customer reviews, and one-click ordering to make buying books as easy and enjoyable as possible. This focus on customer satisfaction helped build brand loyalty and fueled word-of-mouth marketing.

Amazon operated on thin margins, often selling books at a loss to attract customers and gain market share. This aggressive pricing strategy, coupled with frequent discounts and promotions, undercut traditional brick-and-mortar bookstores, making Amazon the go-to destination for price-conscious readers.

As it grew, Amazon continually invested in technology to improve its operations and enhance the customer experience. This included developing sophisticated warehousing and logistics systems to ensure fast and efficient delivery, as well as creating innovative features like the “Look Inside” program, which allowed customers to preview books before purchasing.

Although Amazon initially focused exclusively on selling books, it quickly expanded into other product categories through Amazon Marketplace, becoming a one-stop shop for a wide range of products, from electronics to clothing. This diversification strategy increased revenue and drew more customers to the platform, further solidifying its dominance.

The launch of the Kindle e-reader in 2007 not only popularized e-books but also provided Amazon with a direct channel to sell digital content, thereby bypassing traditional publishers and retailers. The Kindle ecosystem, with its vast library of e-books and user-friendly interface, further strengthened Amazon’s grip on the book market.

Amazon’s rise has had a profound impact on the book industry. Many independent bookstores and chains struggled to compete with their prices and convenience, leading to widespread closures. The American Booksellers Association reported a 43% drop in bookstores five years after Amazon’s first year in business (Jokims, 2024). Publishers have had to adapt to Amazon’s growing power, often negotiating less favorable terms and facing pressure to lower prices. Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing platform empowered authors to self-publish their work, creating a new avenue for reaching readers and bypassing traditional gatekeepers. Finally, the popularity of the Kindle and e-books accelerated the shift towards digital consumption, changing reading habits and forcing publishers to adapt.

Amazon’s dominance has not been without controversy. The company has faced criticism on many fronts. Some authors argue that Amazon’s policies and practices, such as demanding deep discounts and promoting self-published works over traditionally published ones, have negatively affected their earnings. Amazon has been criticized for its labor practices, including allegations of harsh working conditions and low wages in its warehouses and fulfillment centers. Concerns have also been raised about Amazon’s market dominance and its potential to stifle competition in the book industry.

Despite the controversies, Amazon’s dominance in the book industry shows no signs of waning. The company continues to innovate, expand its offerings, and leverage its vast resources to maintain its position as the leading player in the market. As the book industry continues to evolve in the digital age, Amazon’s influence will likely remain a significant force shaping the future of reading.

Blockbuster Syndrome

Imagine this scenario: A young author has spent the last few years working on a novel, rewriting and revising until the whole thing feels polished, exciting, and fresh. They send out their manuscript and luckily find a literary agent eager to support their work. The agent sells the book to a publisher, netting the author a decent advance; the book goes on to garner great reviews, win some awards, and sell 20,000 copies. To most people, this situation sounds like a dream come true. But in an increasingly commercialized publishing industry that focuses on finding the next blockbuster, this burgeoning author could find it difficult to get their contract renewed.

In an industry increasingly dominated by large media corporations with obligations to stockholders, publishers feel pressured to turn a profit. As a result, they tend to bank on sure-fire best sellers, books they expect to sell millions (or tens of millions) of copies, regardless of literary merit. The industry’s growing focus on a few best-selling authors, known as blockbuster syndrome, often means less support and fewer opportunities for the vast majority of writers who don’t sell millions of copies.

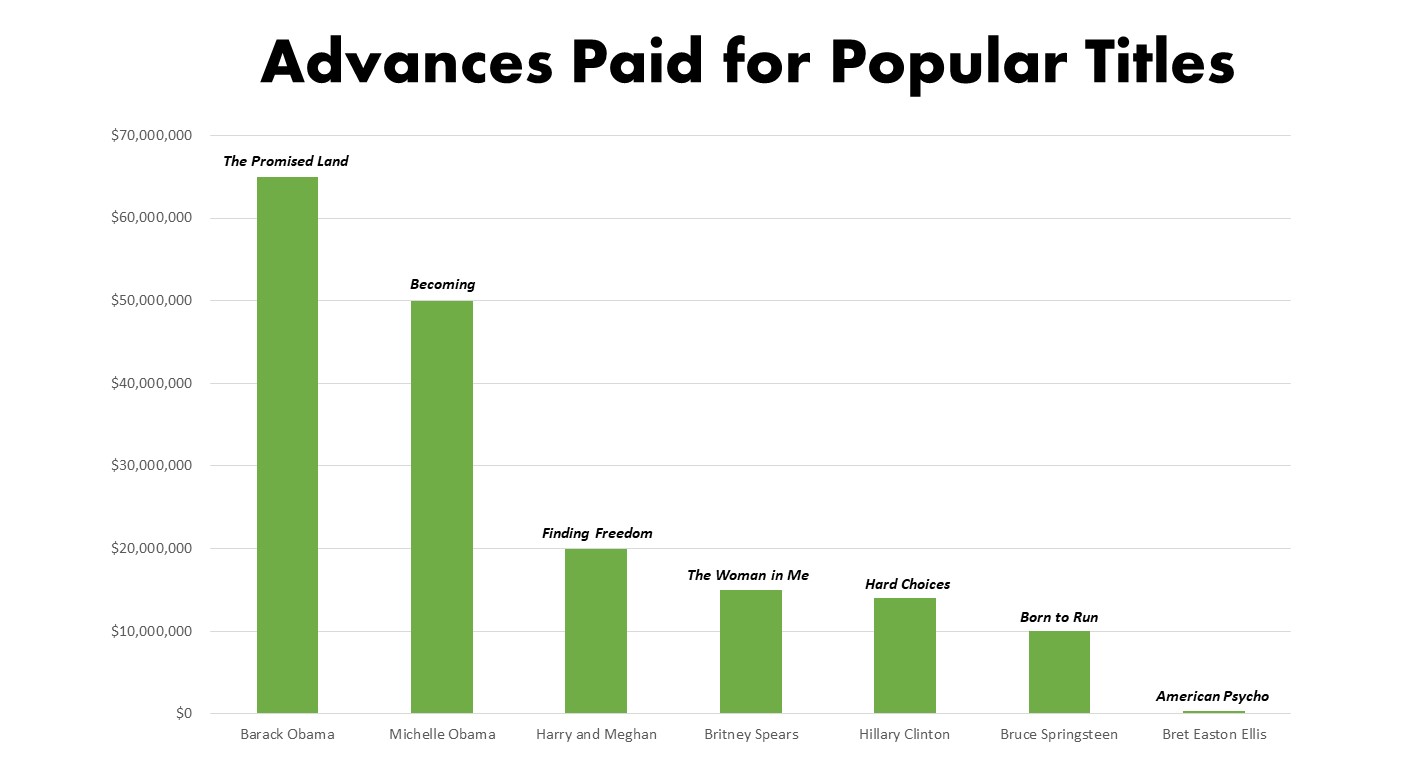

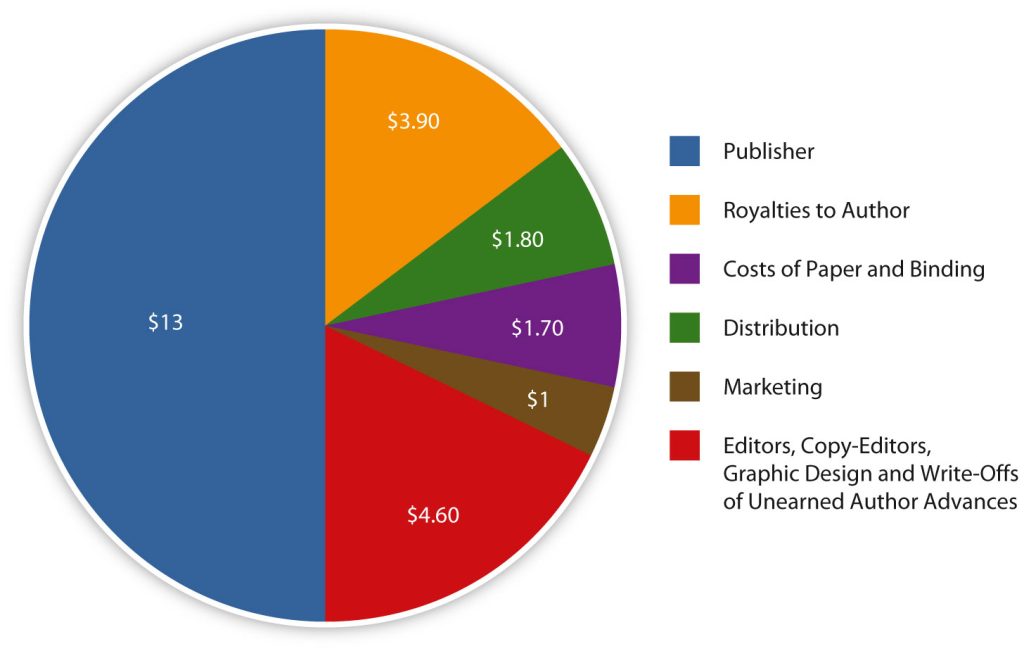

Authors receive an advance, a sum of money paid in expectation of future royalties, a percentage of the book’s sale price. So if a publisher gives an author a $10,000 advance, the author has immediate access to that money, but the first $10,000 worth of royalties goes to the publisher. After that, the author accumulates royalties for every book sold. In this way, an advance operates like a cross between a loan and a gamble. If the book doesn’t sell well, the author doesn’t have to repay the advance; however, they won’t earn any additional money from royalties. However, as many as three-quarters of books don’t earn back their advances, meaning that their authors don’t make any money from sales at all.

Publishers and writers generally do not publicly discuss the actual sums of advances. A New York Times article estimated an average advance to be around $30,000, though exact figures vary widely. These days, though, most of the media attention remains focused on the few books each year that earn their authors huge advances and go on to sell massive numbers of copies—the blockbusters. But the focus on blockbusters can have a damaging effect on emerging writers. Many books by emerging authors get lost in the shuffle. “It used to be that the first book earned a modest advance, then you would build an audience over time and break even on the third or fourth book,” Morgan Entrekin, the publisher of Grove/Atlantic, told The New York Times. “Now the first book is expected to land a huge advance and huge sales…. Now we see a novelist selling 9,000 hardcovers and 15,000 paperbacks, and they see themselves as a failure (Bureau of Labor Statistics).”

Publishers and writers generally do not publicly discuss the actual sums of advances. A New York Times article estimated an average advance to be around $30,000, though exact figures vary widely. These days, though, most of the media attention remains focused on the few books each year that earn their authors huge advances and go on to sell massive numbers of copies—the blockbusters. But the focus on blockbusters can have a damaging effect on emerging writers. Many books by emerging authors get lost in the shuffle. “It used to be that the first book earned a modest advance, then you would build an audience over time and break even on the third or fourth book,” Morgan Entrekin, the publisher of Grove/Atlantic, told The New York Times. “Now the first book is expected to land a huge advance and huge sales…. Now we see a novelist selling 9,000 hardcovers and 15,000 paperbacks, and they see themselves as a failure (Bureau of Labor Statistics).”

Potential blockbusters come at a high price for the publisher as well. They threaten to eat up publicity budgets and dominate publishers’ attention. A huge advance will only pay off if a massive number of copies are sold, which makes publishing houses less likely to take a gamble on unconventional books. This can also lead to publishers producing a glut of similar books. After Suzanne Collins’ huge success with The Hunger Games in 2008, publishers released a flood of similar dystopian and post-apocalyptic stories, such as Divergent by Veronica Roth (2011) and The Maze Runner by James Dashner (2009). While some of these achieved success, many others failed to capture the same level of interest from readers, resulting in a glut of dystopian fiction in the market.

The dominance of a few heavily promoted blockbusters continues. Still, the increasing popularity of digital formats and the rise of self-publishing have contributed to a more diverse and competitive market. To a certain extent, focusing on blockbusters has worked for the publishing industry. Today’s best sellers sell more copies than best sellers did 10 years ago and make up a larger share of the market. However, overall book sales have remained relatively steady. A few heavily promoted blockbusters make up the majority of all sales. However, the blockbuster syndrome threatens to damage the industry in other ways. In a best-seller-driven system, literature becomes a commodity, with little value placed on a book’s artistic merit. Instead, the primary concern depends on whether or not the book will sell.

Beyond the Blockbuster: How Writers are Rewriting Publishing Rules

Discontented with the industry’s focus on blockbusters at the expense of other books, some authors have taken control of publishing their materials. John Edgar Wideman, a finalist for the National Book Award, the 2016 recipient of the MacArthur Genius Award, and the only writer to have won the International PEN/Faulkner Award twice, has published more than 20 books through the traditional publishing system. But when it came time to publish his new collection of short stories, Briefs: Stories for the Palm of the Mind, he decided to try something new. “The blockbuster syndrome is a feature of our social landscape that has gotten out of hand,” Wideman said. “Unless you become a blockbuster, your book disappears quickly. It becomes not only publish or perish, but sell or perish (Reid, 2010).” Wideman eventually decided to team up with self-publishing service Lulu, which meant that he gave up a traditional contract and advance payment in favor of greater control and a higher percentage of royalties. Other authors have turned away from the Big Five publishers and sought out independent publishing houses, which often offer more favorable payment structures. McSweeney’s offers low advances and splits all profits with the author evenly. Vanguard offers no advances, but gives authors high royalties and guarantees a high marketing budget. These nontraditional systems offer authors greater flexibility at a time when the publishing industry is facing rapid change. As Wideman puts it, “I like the idea of being in charge. I have more control over what happens to my book. And I have more control over whom I reach (Reid, 2010).”

Rise (and Fall?) of Book Superstores

In the late 20th century, a new group of colossal bookstores reshaped the retail sale of books in the United States. Two of the most well-known and prevalent book retailers, Barnes & Noble and Borders (the largest and second-largest book retailers in the United States, respectively), expanded extensively by building book superstores in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These large retail outlets differed from traditional, smaller bookstores in several ways. They often sold a variety of products, including books, calendars, paper goods, and gifts. Many also have in-store cafes, allowing patrons to browse books and sip lattes under the same roof. They also frequented physically larger spaces, and such megastores drew customers due to their wide selection and ability to offer books at deeply discounted prices. Borders went out of business in 2011 because the company failed to adapt to digital platforms like Barnes & Noble, which had released its Kindle e-reader in 2007 and had performed well recently by allowing each store more creative control over the type and quantity of content offered (Thompson, 2019).

Many independent bookstores couldn’t compete with the large chains’ discounts, wide selection, and upscale atmosphere. According to Publishers Weekly, independent booksellers’ share of the book market fell from 58 percent in 1972 to 15.2 percent in 1999. The American Booksellers Association (ABA), a trade association of bookstores, notes that its membership peaked at 5,200 in 1991; by 2005, that number had declined by 65 percent to 1,791. The decline of the independent bookstore coincided with the consolidation of the publishing industry, and some supporters of independent bookstores see a link between the two. Richard Howorth—owner of Square Books—an independent bookstore in Oxford, Mississippi, told Mother Jones magazine that “when the independent bookselling market was thriving in the ’70s and ’80s, more books were being published, more people were reading books, the sales of books were higher, and publishers’ profit margins were much greater. With the rise of the corporate retailing powers and the consolidation in publishing, all of those things have declined (Gurwitt, 2000).” Book superstores emphasized high turnover and high-volume sales, placing a greater emphasis on bestsellers and returning some mass-market paperbacks to publishers after only six weeks on the shelves.

Although the dominance of book superstores has declined in recent years, they continue to play a significant role in the book market. The rise of online retailers, such as Amazon, has posed a considerable challenge to traditional bookstores, including superstores. However, many book superstores have adapted by focusing on in-store experiences, offering curated selections, and partnering with local authors and communities. As a result, they continue to attract customers seeking a physical browsing experience and personalized recommendations. These stores didn’t specialize in books and tended to offer only a few heavily promoted blockbuster titles. Large discount stores can negotiate favorable deals with publishers, allowing them to offer discounts on books that are even more substantial than those provided by book superstores in some cases.

Still, problems remain. Costco announced that it would stop regularly selling books in its warehouses starting in January 2025, due to the labor-intensive process of setting up displays (Harris and Alter, 2024). In more recent years, book superstores have also faced a threat from the increasing number of books purchased online. As of 2023, Amazon, the largest online bookseller, accounted for around 30 to 40 percent of book sales in the United States. Its market share has continued to grow over the years, driven by factors such as its vast product selection, convenient shopping experience, and Prime membership benefits.

The shift away from independent bookstores and toward larger retailers, such as book superstores or non-specialized retailers like Walmart, has benefited the industry in some ways, most notably by making books cheaper and more widely available. Mega best sellers, such as the Harry Potter and Twilight series, set sales records at least in part because consumers could purchase the books in malls, convenience stores, supermarkets, and other nontraditional venues. However, overall book sales have not risen. Although consumers may pay less for the books they purchase through these retailers, they may also lose something in return. Jonathan Burnham, a publisher from HarperCollins, discussed the value of independent bookstores with The New Yorker, noting how they are similar to community centers: “There’s a serendipitous element involved in browsing…. We walk in and know the people who work there and like to hear their reading recommendations.”

Price Wars

Part of the reason book superstores succeeded in crowding out smaller, independent retailers lay in their ability to offer significant discounts on a book’s cover price. Because the big chains sell more books, they can negotiate better deals with publishers and then pass the discounts to their customers. Not surprisingly, deep discounts appeal to customers, which helped the book superstores gain such a large share of the market in the 1990s. The superstores can sell books at such a sharp discount, sometimes even half of the listed price, because their higher sales numbers give them bargaining power with the publishers. Independent bookstores buying the books at a normal wholesale rate (usually half the list price) operate at a disadvantage; they can’t offer deep discounts and, as a result, they must charge higher prices than the superstores. This deep discount policy explains why sales of bestsellers have risen over the past decade, as book superstores typically slash the prices of bestsellers and new releases. However, large discounts encourage high-volume selling, and emphasizing high-volume selling encourages safe publishing choices. Bookstores can only make money if they sell a large number of copies, and that usually means blockbuster works by established authors. While the threat of deep discounting remains a concern for independent bookstores and the publishing industry, the regulatory landscape has undergone significant evolution in recent years. Some countries have implemented price controls or minimum resale price maintenance (MSRP) laws to protect booksellers. For example, France continues to have strict price controls, limiting discounts to 5%. However, critics have debated the effectiveness of such regulations, with some arguing that they stifle competition and innovation.

In other regions, such as the United States, the market has primarily been left unregulated. This has led to increased competition and the rise of online retailers like Amazon, which often offer significant discounts on books. As a result, many independent bookstores have faced challenges in competing with these large players.

The brick-and-mortar bookstores have even more competition. Wal-Mart and other discount retailers sell more copies of the few books they offer at their stores so that they can negotiate even more favorable terms with publishers. Amazon, which dominates online book sales, routinely discounts books 20 percent or more.

Other online retailers have attempted to compete with Amazon for online book sales profit dominance. The competitive landscape of the book market has intensified since 2009, with online retailers like Amazon and brick-and-mortar giants like Walmart engaging in aggressive price wars. In recent years, similar instances of price matching and undercutting have occurred between these major players, particularly during peak sales periods such as the holiday season. While the specific tactics may have evolved, the underlying theme of intense competition for market share remains a defining characteristic of the modern book industry.

While it may seem comical that major retailers duke it out over mere pennies, book retailers, from independent to large chains, find the situation quite sobering. The startling thing about the price wars among Amazon, Target, and Wal-Mart was that no one involved expected to make any money from these deeply discounted books. At $9 or less, these books were almost certainly sold at a price below retail value, perhaps by quite a lot.

If a book’s list price is $35, its wholesale price is usually around half of that, in this case $17. If the book is priced at $9, that means an $8 loss to the retailer per copy. Although at first this seems like blatantly bad business, it works because all of these retailers are in the business of selling much more than just books. Large online retailers use deep discounts to lure customers to their websites, hoping that these customers will purchase other items. These book sales serve a valuable purpose by driving traffic to the retailer’s website. However, booksellers whose primary business is selling books, such as local independent bookstores, cannot afford this luxury.

E-books have also entered the retail struggle. Because they incur lower printing costs, e-books are relatively inexpensive to produce, and consumers expect to see the savings reflected in their purchase. However, book publishers still sell the books to distributors at wholesale prices—about half of the retail value of the hardcover version. To attract buyers, companies such as Amazon charge only $9.99 for the average e-book, once again incurring a loss (Stone & Rich, 2009). Online businesses hope to offset the cost differential with device sales—consumers may be more likely to spend hundreds of dollars on an inexpensive reader to access cheaper books. While major retailers may eventually profit from this sales method, many wonder how long it will last. Author David Baldacci argues that a book industry based solely on profit isn’t sustainable. In the end, he argues, “there won’t be anyone selling [books] anymore because you just can’t make any money (Rich, 2009).”

The inclination to focus solely on net profits reflects a broader trend in the book industry. While the retail landscape has evolved in recent years, with some traditional brick-and-mortar stores facing challenges, online retailers like Amazon have continued to expand their reach. This increased competition has generally led to lower prices for consumers, although the overall trend has been influenced by factors such as inflation and supply chain disruptions. As for popular books, they continue to receive significant attention, driven by marketing campaigns, social media buzz, and recommendations from influencers and book clubs. While this has positive short-term results for consumers and large retailers, the effects have proven devastating for most authors and smaller bookstores. Although in the end, the introduction of e-books may cause no more harm to the industry than the explosion of paperbacks in the early 1900s, the larger emphasis on quantity over quality threatens the literary value and sustainability of books.

Diversification and Inclusion

Readers have actively sought out books by authors from marginalized communities, and publishers have responded by acquiring and promoting a wider range of voices to meet this demand for diverse voices and stories. Inclusion has spread beyond authorship as the publishing industry has pushed for greater diversity among its staff and executives to ensure that all diverse perspectives are represented at all levels of the industry.

College Textbooks

In a significant departure from the typical book market, the selection of textbooks is often made by individuals other than the end-users—the students. This unique dynamic plays out against a backdrop where students annually spend, on average, a substantial $1,212 on textbooks and supplies. Furthermore, schools frequently receive a percentage of these sales, creating an additional financial incentive within the system.

Publishers, aiming to protect their profits, actively attempt to discourage the used-book market. This effort is particularly noteworthy given that textbooks are ostensibly designed to impart objective knowledge. However, the values embedded within these texts are conveyed not only through what is included but equally through what is omitted. A prominent example of this complex interplay between objectivity, values, and market forces can be seen in the historical controversies surrounding high school science textbooks, particularly regarding the inclusion of evolution and/or creationism.

The Evolution of Bookselling

While online retailers like Amazon remain dominant, independent bookstores have made a comeback by often serving as community hubs and offering curated selections and personalized recommendations.

Hybrid publishing models have also emerged, providing authors with more options than ever, with a range of hybrid models that blend elements of traditional publishing and self-publishing. Self-publishing platforms, such as BookBaby and Draft2Digital, and crowdfunding platforms, like Kickstarter, offer modern authors opportunities to publish their work without relying on traditional book publishers.

Focus on Direct-to-Consumer Marketing

Publishers have increasingly built direct relationships with readers. This involves strategies like email newsletters, author websites, and online events to engage readers and promote books directly. By utilizing data analytics, publishers have gained insight into readers’ preferences, tracked book sales, and tailored marketing campaigns more effectively.

Print Books Remain Relevant

Despite the rise of digital formats, print books still enjoy popularity. Many readers still prefer the tactile experience of reading a physical book, and print books remain popular as gifts and collectibles. As a result, publishers have experimented with print formats and designs to create visually appealing and high-quality print books that cater to the preferences of print book lovers.