5.2 History of Magazine Publishing

Like the newspaper, the magazine has a complex history shaped by the cultures in which it developed. Examining the industry’s roots and its transformation over time can contribute to a better understanding of the modern industry.

Early Magazines

After the printing press became prevalent in Europe, early publishers began to conceptualize the magazine. Forerunners of the familiar modern magazine first appeared during the 17th century in the form of brochures, pamphlets, and almanacs. Soon, publishers realized that irregular publication schedules required too much time and energy. A gradual shift then occurred as publishers sought regular readers with specific interests. However, the early magazine bore distinct differences from previous publications. It did not provide a variety of news stories like a newspaper, but it also lacked the characteristics of pleasure reading. Instead, early magazines occupied the middle ground between the two (Encyclopedia Britannica).

Germany, France, and the Netherlands Lead the Way

German theologian and poet Johann Rist published the first actual magazine between 1663 and 1668. Titled Erbauliche Monaths-Unterredungen, or Edifying Monthly Discussions, Rist’s publication inspired several others to begin printing literary journals across Europe: Denis de Sallo’s French Journal des Sçavans (1665), the Royal Society’s English Philosophical Transactions (1665), and Francesco Nazzari’s Italian Giomale de’letterati (1668). In 1684, the exiled Frenchman Pierre Bayle published Novelles de la République des Lettres in the Netherlands to escape French censorship. Profoundly influenced by the general revival of learning during the 1600s, these publications inspired enthusiasm for education.

Another Frenchman, Jean Donneau de Vizé, published the first “periodical of amusement,” Le Mercure Galant (later renamed Mercure de France), in 1672, which contained news, short stories, and poetry. This combination of news and pleasurable reading became incredibly popular, causing other publications to imitate the magazine (Encyclopedia Britannica). This lighter magazine catered to a different reader than did the other, more intellectual publications of the day, offering articles for entertainment and enjoyment rather than for education.

With the arrival of the 18th century came an increase in literacy. Women, who enjoyed a considerable rise in literacy rates, began reading in record numbers. This growth had a profound impact on the literary world as a whole, inspiring a large number of female writers to publish novels specifically for female readers (Wolf). This influx of female readers also helped magazines flourish as more women sought out the publications as a source of knowledge and entertainment. Many magazines seized the opportunity to target women. The Athenian Mercury, the first magazine written specifically for women, appeared in 1693.

British Magazines Appear

Much as in newspaper publication, Great Britain closely followed continental Europe’s lead in producing magazines. During the early 18th century, three major influential magazines were published regularly in Great Britain: Daniel Defoe’s The Review, Sir Richard Steele’s The Tatler, and Joseph Addison and Steele’s The Spectator.

All three of these publications reached their audiences daily or several times a week. While they reached readers as frequently as newspapers, their content differed. The Review focused primarily on domestic and foreign affairs, featuring opinion-based political articles. The Spectator replaced the Tatler, which was published from 1709 to 1711. Both Tatler and Spectator emphasized living and culture, frequently using humor to promote virtuous behavior (Wolf). Tatler and Spectator, in particular, drew a large number of female readers, and both magazines eventually introduced female-targeted publications: the Female Tatler in 1709 and the Female Spectator in 1744.

In the bustling intellectual landscape of 18th-century London, a quiet revolution was brewing, spearheaded by Edward Cave. His brainchild, The Gentleman’s Magazine, wasn’t just another publication; it was a pioneering endeavor that forever changed the way information was disseminated.

Cave, a printer and editor with an astute eye for innovation, sought a new way to consolidate the diverse array of news, essays, poems, and debates that typically circulated in individual pamphlets and newspapers. He envisioned a single, comprehensive repository for all this disparate content, a veritable “storehouse of knowledge.” It was this very concept that led him to christen his publication a “magazine.”

At the time, the word “magazine” held a more literal meaning, rooted in its French and Arabic origins: a physical place where goods, provisions, or military supplies were stored or sold. Think of a well-stocked armory or a bustling mercantile warehouse – a place where one could find a variety of essential items. Cave ingeniously repurposed this term, applying it metaphorically to his printed collection. The Gentleman’s Magazine was, in essence, a literary emporium, a place where readers could find a curated selection of intellectual provisions, all conveniently gathered under one cover.

Thus, with its inaugural issue in 1731, The Gentleman’s Magazine not only offered a groundbreaking format for information, but it also cemented a new meaning for an old word, forever linking “magazine” with the vibrant, eclectic world of periodicals known today.

American Magazines

The first American magazines debuted in 1741, when Andrew Bradford’s American Magazine and Benjamin Franklin’s General Magazine began publication in Philadelphia, a mere three days apart from each other. Neither magazine lasted long, however; American Magazine folded after only three months and General Magazine after six. The short-lived nature of the publications likely had less to do with the outlets themselves and more to do with the fact that they faced “too few readers with leisure time to read, high costs of publishing, and expensive distribution systems (Straubbhaar, et. al., 2009).” Despite this early setback, magazines began to flourish during the latter half of the 18th century, and by the end of the 1700s, more than 100 magazines had emerged in the nascent United States. Despite this prominent publication figure, typical colonial magazines still recorded low circulation figures, and audiences considered the available material to be highbrow.

Mass-Appeal Magazines

Magazines gained popularity in the United States in the 1830s, when publishers began taking advantage of a general decline in printing and mailing costs and started producing less-expensive magazines with a wider target audience in mind. Magazine style also transformed. While early magazines focused on improvement and reason, later versions shifted their focus to amusement. Magazines no longer focused on the elite class. Publishers took advantage of their newly expanded audience and began offering family magazines, children’s magazines, and women’s magazines. Women’s publications again proved especially lucrative. Godey’s Lady’s Book, a Philadelphia-based monthly published between 1830 and 1898, reached out to female readers by employing nearly 150 women.

Muckraking

Born out of the tumultuous late 19th and early 20th centuries, muckraking emerged as a distinctive and potent force in American journalism, spanning the years roughly from the 1870s to the 1920s. This American-English term, famously coined in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt—who drew inspiration from a character in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress—referred to those intrepid investigators who delved into and exposed the insidious roots of corruption in society.

Muckraking wasn’t merely about reporting facts. Publications would embark on ambitious “crusades” aimed at eradicating pressing social problems. This journalistic offensive typically followed a three-step process: first, discovering a pressing social ill; second, writing about it repeatedly and relentlessly, shining a persistent light on the issue; and finally, through this sustained public pressure, forcing the government to intervene and implement solutions.

Among the most formidable figures of this era was Samuel McClure, whose McClure’s Magazine became a prominent platform for articles dissecting the shadowy dealings of the insurance industry, the monopolistic practices of railroads, and the pervasive rot of government corruption. One of McClure’s most celebrated contributors was Ida May Tarbell, whose groundbreaking investigation into the monolithic Standard Oil Company trust remains a landmark of investigative journalism.

Lincoln Steffens, who began his career at the New York Sun, was another titan of muckraking. Working the police beat, he witnessed firsthand the brutal realities of officer misconduct, fueling his outrage. His most renowned work, The Shame of the Cities, unflinchingly exposed the deep-seated problems plaguing numerous American urban centers and the rampant corruption among elected officials. Upton Sinclair, a prolific writer with over 80 books to his name, penned the iconic novel The Jungle, which graphically depicted the horrific conditions in the meatpacking industry, and also delved into the intricacies of the oil and coal industries.

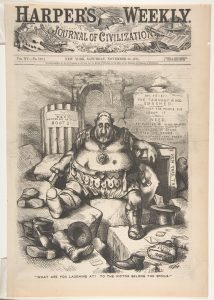

Beyond the written word, the visual medium also served as a powerful tool for muckraking. Cartoonist Thomas Nast stands out, celebrated for two enduring legacies: his definition of the modern image of Santa Claus and his scathing political cartoons targeting the notoriously corrupt New York Democratic Party leader, Boss Tweed, and his Tammany Hall machine. So impactful were Nast’s visual indictments that President Grant, in 1869, famously declared, “Two things elected me. The sword of Sheridan and the pencil of Nast.” Boss Tweed, whose reign of corruption in 1871 is estimated to have siphoned between $25 million and $45 million (and potentially as high as $200 million, or $5 billion in 2023 dollars) from New York City taxpayers, was eventually brought to justice, a testament to the power of such relentless scrutiny.

The popularity of muckraking was deeply rooted in the socio-economic conditions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 1890s saw a significant decline in average American incomes and an increase in unemployment. The average work week stretched to a grueling 60 hours, while typical weekly salaries hovered between a meager $6 and $10. Industrialization, while bringing progress, also fostered the rise of powerful trusts that ruthlessly cornered markets and inflated prices, further squeezing the working class. This era was also characterized by a relatively weak federal government, with a line of presidents from Lincoln to Roosevelt often limiting intervention in the affairs of big business, leaving a void that muckrakers were eager to fill by holding power accountable through the unflinching gaze of their investigations.

The Saturday Evening Post

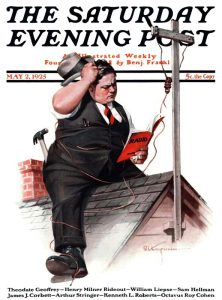

The Saturday Evening Post became the first truly successful mass-circulation magazine in the United States. This weekly magazine first began printing in 1821 and remained in regular print production until 1969, when it briefly ceased circulation. However, in 1971, a new owner remodeled the magazine to focus on health and medical breakthroughs. From its first publication in the early 1800s, The Saturday Evening Post quickly gained popularity; by 1855, it had a circulation of 90,000 copies per year (Saturday Evening Post). Widely recognized for transforming the look of the magazine, the publication became the first to use artwork on its cover, a decision that The Saturday Evening Post has said “connected readers intimately with the magazine as a whole (Saturday Evening Post).” Indeed, the Saturday Evening Post took advantage of the format by featuring the work of famous artists such as Norman Rockwell. Using such recognizable artists boosted circulation as “Americans everywhere recognized the art of the Post and eagerly awaited the next issue because of it (Saturday Evening Post).”

But The Saturday Evening Post did not only feature famous artists; it also published works by well-known authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, and Ring Lardner. The popularity of these writers contributed to the magazine’s continued success.

Youth’s Companion

The Youth’s Companion represents another early U.S. mass magazine, published between 1827 and 1929, until it merged with The American Boy. Based in Boston, Massachusetts, this periodical featured fairly religious content and developed a reputation as a wholesome magazine that encouraged young readers to lead virtuous and pious lives. Eventually, the magazine sought to reach a larger, adult audience by including tame entertainment pieces. Nevertheless, the magazine in time began featuring the work of prominent writers for both children and adults. It became “a literary force to be reckoned with (Nineteenth-Century American Children and What They Read).”

Price Decreases Attract Larger Audiences

While magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post and Youth’s Companion proved pretty popular, the industry still struggled to achieve widespread circulation. Most publications cost the then-hefty sum of 25 or 35 cents per issue, limiting readership to the relatively few who could afford them. This all changed in 1893 when Samuel Sidney McClure began selling McClure’s Magazine, originally a literary and political magazine, at the bargain price of only 15 cents per issue. The trend caught on. Soon, Cosmopolitan (founded 1886) began selling for 12.5 cents, while Munsey Magazine (1886–1929) sold for only 10 cents. All three of these periodicals enjoyed wide success. Frank A. Munsey, owner of Munsey Magazine, estimated that between 1893 and 1899 “the ten-cent magazine increased the magazine-buying public from 250,000 to 750,000 persons (Encyclopedia Britannica).” For the first time, magazines could sell for less than they cost to produce. Due to increased circulation, publications could charge higher fees for advertising space and lower the cost to the customer.

By 1900, advertising had become a crucial component of the magazine business. In the early days of the industry, many publications attempted to exclude advertisements from their issues due to publishers’ natural fondness for literature and writing (Encyclopedia Britannica). However, once circulation increased, advertisers sought out space in magazines to reach the larger audience. Magazines responded by raising advertising rates, ultimately increasing their profitability. By the turn of the 20th century, advertising became the primary source of income for most magazines. This trend becomes particularly noticeable in some women’s magazines, where advertisements account for nearly half of all content.

Early 20th-Century Developments

The arrival of the 20th century brought with it new types of magazines, including news, business, and picture magazines. In time, these types of publications came to dominate the industry and attract vast readerships.

Newsmagazines

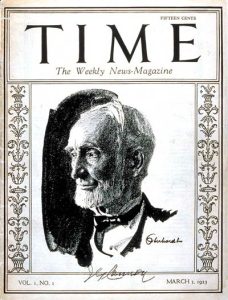

As publishers became interested in succinctly presenting the fresh increase of worldwide information that technology made available during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they designed the newsmagazine. In 1923, Time became the first newsmagazine that focused on world news. Time first began publication with the proposition that “people are uninformed because no publication has adapted itself to the time which busy men are able to spend simply keeping informed (Encyclopedia Britannica).” Although the periodical struggled during its early years, Time hit its stride in 1928, and its readership grew. The magazine’s signature style, characterized by well-researched news presented succinctly, contributed significantly to its eventual success.

Several other newsmagazines came onto the market during this era as well. Business Week debuted in 1929, focusing on the global market. Forbes, currently one of the most popular financial magazines, began printing in 1917 as a biweekly publication. In 1933, a former Time foreign editor founded Newsweek, which now has a circulation of nearly 4 million readers. Today, Newsweek and Time continue to compete with each other, furthering a trend that began in the early years of Newsweek.

Picture Magazines

Photojournalism, the art of telling stories through photography, also gained popularity during the early 20th century. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce ignited the nascent spark of photojournalism in 1826 by capturing the world’s first photograph. Yet, for decades, images such as these remained largely absent from the daily news, their widespread integration into newspapers awaiting the tumultuous conclusion of a conflict that would forever alter the American landscape.

As the drums of the Civil War began to beat, a voracious public demand for timely battle news emerged, and pictorial weekly newspapers rose to the occasion. These publications, a precursor to modern news magazines, became windows into the conflict, their pages often adorned with gory illustrations. These weren’t artistic interpretations; they were stark, visceral depictions, usually based directly on the photographs emerging from the front lines.

At the heart of this visual revolution stood Matthew Brady, a figure often credited with birthing photojournalism. His ambition was monumental: to document and preserve the unfolding history through the lens of his camera. However, history’s judgment of Brady is not without its shadows. He is frequently criticized for staging his subjects, even going so far as to arrange the corpses of fallen soldiers to achieve a more dramatic composition. Furthermore, while he spearheaded a team of talented photographers, individual credit was often subsumed under the umbrella of his studio, a practice that blurs the lines of authorship even today.

The Civil War era itself was a crucible for journalistic innovation. Paper shortages, particularly in the beleaguered South, forced ingenuity. The conflict also saw the unprecedented formation of press pools and the issuance of press credentials, signaling a growing recognition of the media’s role in shaping public opinion. For the first time, war correspondents were specifically hired, their daring exploits on the front lines transforming them into heroes, often referred to as “specials.” The burgeoning reliance on the telegraph, a technological marvel of its time, ensured that these dispatches were not only timely but also factual and concise, their brevity dictated by the cost of transmission.

While Brady laid the groundwork, the true democratization of photographs in newspapers awaited the 1880s and the advent of the halftone process. This revolutionary technique enabled photographs to be broken down into a series of dots, appearing in various shades of gray, and, crucially, allowed for the direct mechanical replication of images onto newsprint. No longer reliant on laborious engravings, newspapers and magazines could now integrate photographs swiftly and affordably.

The visual landscape of journalism continued to evolve. In 1888, National Geographic debuted, destined to become a global arbiter of visual storytelling. And in a further leap forward, the magazine introduced color plates in 1906, ushering in an era where the world could be presented not just in shades of gray, but in the full, vibrant spectrum of reality.

As photography grew in popularity, so did picture magazines. The most influential picture magazine was Henry Luce’s Life, which regularly published between 1936 and 1972. Within weeks of its initial publication, Life had a circulation of 1 million. In Luce’s words, the publication aimed “to see life; to see the world; to witness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things (Encyclopædia Britannica).” It did not disappoint. Widely credited with establishing photojournalism, Life captured the attention of many upon its first publication. With 96 large-format glossy pages, even the inaugural issue sold out. The opening photograph depicted an obstetrician holding a newborn baby, accompanied by the caption “Life begins.”

While Life was the most influential picture magazine, it had competition. The popular biweekly picture magazine Look was published between 1937 and 1971, claiming to compete with Life by reaching a larger audience. Although Look offered Life stiff competition during their almost identical print runs, the latter magazine has left a greater legacy. Several other photo magazines—including Focus, Peek, Foto, Pic, and Click—also took their inspiration from Life.

Framing History: How Bourke-White Defined Life‘s Legacy

In the annals of photojournalism, few names resonate with the same pioneering spirit and enduring impact as Margaret Bourke-White. Her significance is inextricably linked to the birth and meteoric rise of Life magazine, a publication that fundamentally redefined how news was consumed, presenting the world through the compelling narrative of photographs.

Bourke-White was not merely a contributor to Life; she was a foundational pillar of the magazine. Her arresting image of the Fort Peck Dam graced the cover of Life’s inaugural issue in 1936, immediately signaling the magazine’s commitment to visual storytelling and establishing her as a leading voice in this burgeoning field. She was one of the magazine’s first four staff photographers and the only woman among them, a testament to her undeniable talent and tenacious spirit in a male-dominated profession.

Her career with Life spanned decades and took her to the heart of the 20th century’s most pivotal moments. From documenting the grim realities of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl to becoming the first Western photographer permitted to capture the industrialization of the Soviet Union, Bourke-White’s lens offered unprecedented access and insight. She was truly “Maggie the Indestructible,” a moniker given by her colleagues for her unwavering resolve in the face of danger. She became the first accredited female war correspondent, flying on bombing missions during World War II and bearing witness to the horrors of liberated concentration camps like Buchenwald, her photographs profoundly shaping public understanding of the conflict. Later, her work illuminated the complexities of India’s partition and the nascent struggles against apartheid in South Africa. Throughout her Life, Margaret Bourke-White didn’t just take pictures; she crafted visual essays that brought distant events and human stories directly into American homes. Her work underscored the immense power of photography to not only document history but to provoke empathy, challenge perceptions, and ultimately, force a reckoning with the world’s most pressing issues.

Her legacy is thus intertwined with Life’s mission: to present the news not just through words, but through the evocative, immediate, and unforgettable language of the photograph.

Into the 21st Century

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the advent of online technology began to greatly affect both the magazine industry and the print media as a whole. Much like newspaper publishers, magazine publishers have had to rethink their business models to reach an increasingly online audience. The chapter will discuss specifics of the changes made to the magazine industry in further detail later in this chapter.