6.3 The Reciprocal Nature of Music and Culture

Music and culture have a tight-knit relationship. For example, policies on immigration, war, and the legal system can influence artists and the type of music they create and distribute. Music may then influence cultural perceptions of race, morality, and gender, which can, in turn, shape people’s attitudes toward those policies.

Cultural Influences on Music

A myriad of cultural influences shaped the evolution of popular music in the United States in the 20th century. Rapidly shifting demographics brought previously independent cultures into contact, creating new cultures and subcultures, and music evolved to reflect these changes. Migration, the evolution of youth culture, and racial integration exemplify the most important cultural influences on music.

Migration

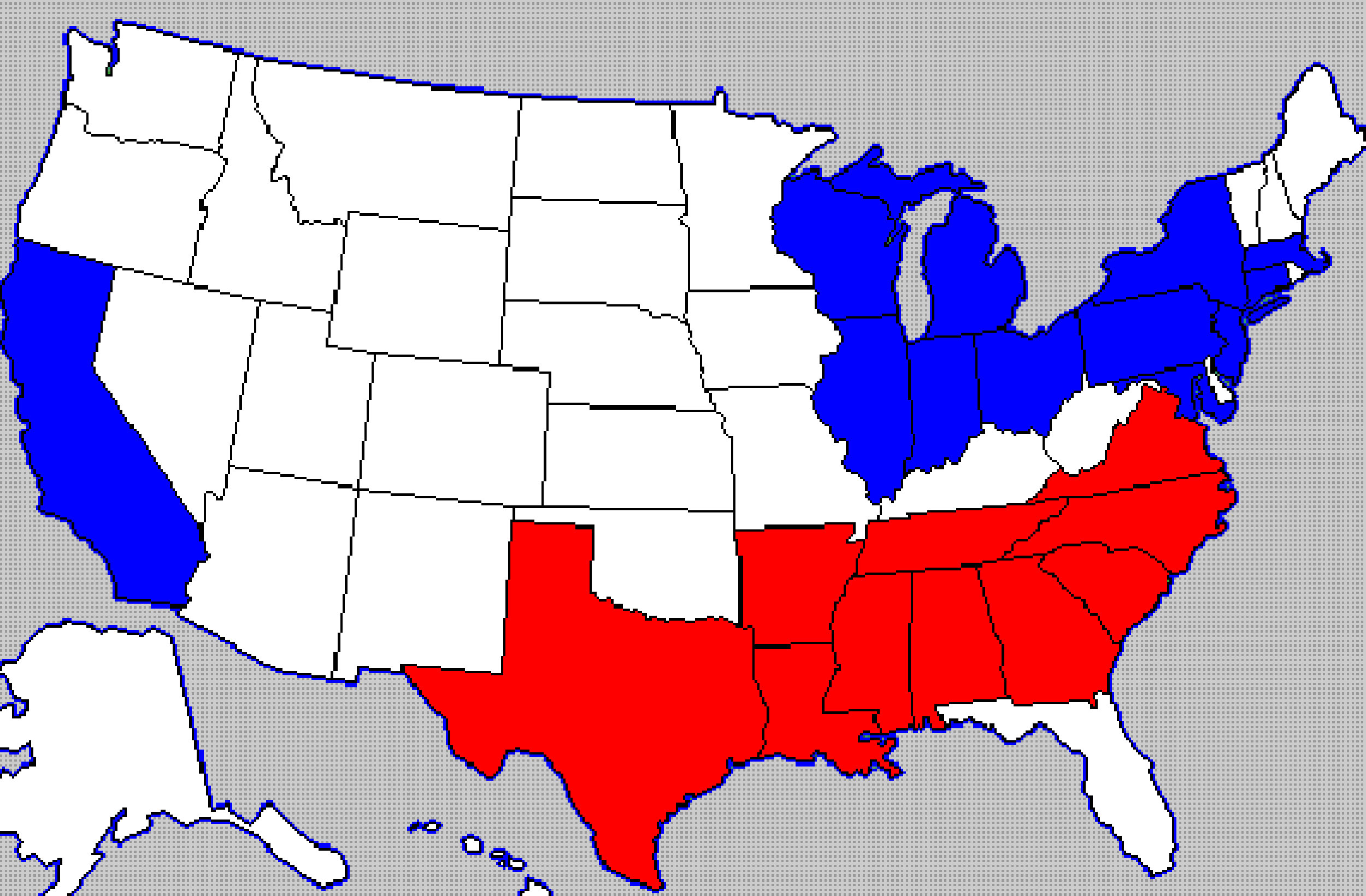

Migration has been a significant cultural influence on the popular music industry over the past century. In 1910, 89 percent of Black Americans still lived in the South, most of them in rural farming areas (Weingroff, 2011). Three years later, a series of disastrous events devastated the cotton industry. World cotton prices plummeted, a boll weevil beetle infestation destroyed large areas of crops, and in 1915, flooding destroyed many of the houses and crops of farmers along the Mississippi River. Already suffering from the restrictive “Jim Crow” laws that segregated schools, restaurants, hotels, and hospitals, Black sharecroppers began to look to the North for a more prosperous lifestyle. An economic boom in the Northern states resulted from increased demand for industrial goods due to the war in Europe. These states needed labor because the war had slowed the rate of foreign immigration to Northern cities. Between 1915 and 1920, as many as 1 million Black individuals migrated to Northern cities in search of employment, followed by another million throughout the subsequent decade (Nebraska Studies, 2010). The mass exodus of Black farmers from the South became known as the Great Migration, and by 1960, 75 percent of all Black Americans lived in cities (Emerging Minds, 2005). The Great Migration had a huge impact on political, economic, and cultural life in the North, and popular music reflected this cultural change.

Some of the Black individuals who moved to Northern cities came from the Mississippi Delta, home of the blues. Many of these individuals ended their journey in Chicago. Delta-born pianist Eddie Boyd later told Living Blues magazine, “I thought of coming to Chicago where I could get away from some of that racism and where I would have an opportunity to, well, do something with my talent…. It wasn’t peaches and cream, man, but it was a hell of a lot better than down there where I was born (Szatmary).” At first, the migrants brought their style of country blues to the city. Characterized by the guitar and the harmonica, the Delta blues employed a rhythmic structure and strong vocals heavily influenced by musicians such as Charley Patton and legendary guitarist Robert Johnson. However, as the urban setting began to affect the migrants’ style, they started to record a hybrid of blues, vaudeville, and swing, incorporating boogie-woogie and rolling bass piano. Mississippi-born guitarist Muddy Waters, who moved to Chicago in the early 1940s, revolutionized the blues by combining his Delta roots with an electric guitar and amplifier. He did so partly out of necessity since he could barely make himself heard in crowded Chicago clubs with an acoustic guitar (Chicago Blues Guitar). Waters played a peppier and more buoyant style than the sullen country blues. His plugged-in electric blues became the hallmark of the Chicago blues style, influencing countless other musicians and laying the groundwork for rock and roll. Other migrant bluesmen contributed to the creation of regional variations of the blues throughout the country, including John Lee Hooker in Detroit, Michigan, and T-Bone Walker in Los Angeles, California.

Youth Culture

Before 1945, most music was created with adults in mind, and the industry barely considered teenage musical tastes. Young adults had few freedoms—most males had to choose between joining the military or getting a job to support their fledgling families. At the same time, society expected most females to marry young and have children. Few young adults attended college, and opportunities to express personal freedom were limited. Following World War II, this situation changed drastically. A booming economy helped create the American middle class, which in turn created an opening for a youth consumer culture. Unpleasant memories of the war discouraged some parents from forcing their children into the military, and many emphasized the importance of enjoying life and having a good time. As a result, teenagers found they had a lot more freedom. This new liberalized culture allowed teenagers to make decisions for themselves, and, for the first time, many had the financial means to do so. Whereas many adults enjoyed the traditional sounds of Tin Pan Alley, teens began to listen to rhythm and blues songs played by radio disc jockeys such as Alan Freed. Increased racial integration within the younger generation made them more accepting of Black musicians and their music, which their peers considered “cool.” It provided a welcome escape from the daunting political and social tension caused by Cold War anxieties. The wide availability of radios, jukeboxes, and 45 rpm records exposed this new style of rock and roll music to a broad teenage audience.

Once teenagers had the buying power to influence record sales, record companies began to notice. Between 1950 and 1959, record sales in the United States skyrocketed from $189 million to nearly $600 million (Szatmary). The 45 rpm vinyl records that were introduced in the late 1940s offered an affordable option for teens with allowances. Dick Clark, a radio presenter in Philadelphia, soon tuned in to the new tastes of teenagers. Sensing an opportunity to tap into a potentially lucrative market, he secured sufficient advertising support to transform the local hit music telecast Bandstand into a national television phenomenon.

This resulted in the 1957 launch of American Bandstand, a music TV show that featured a group of teenagers dancing to current hit records. The show’s popularity prompted record producers to create a legion of rock and roll acts specifically designed to appeal to a teenage audience, including Fabian and Frankie Avalon (Grimes, 2011). During its nearly 40-year run, American Bandstand had a profound influence on teenage fashion and musical tastes, and in turn, reflected contemporary youth culture.

Racial Integration

Following the Great Migration, racial tensions increased in Northern cities. Many Northerners found themselves confronted with the very real issue of having to compete for jobs with Black migrant workers and reacted with and without violence. Black workers found themselves pushed into undesirable neighborhoods, often living in crowded, unsanitary slums where their landlords charged exorbitant rates. During the 1940s, racial tensions boiled over into race riots, most notably in Detroit. The city’s 1943 riot caused the deaths of 34 people, 25 of whom were Black (Gilcrest, 1993).

Frustrated with inequalities in the legal system that distinguished Black and White individuals, members of the civil rights movement pushed for racial equality. In 1948, an executive order granted by President Harry Truman integrated the military. The movement toward equality gained further momentum in 1954 with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to end segregation in public schools in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education. The civil rights movement escalated throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, aided by highly publicized events such as Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat on a bus to a White passenger in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. In 1964, Congress passed the most sweeping civil rights legislation since the Reconstruction Era, forbidding discrimination in public places and authorizing financial aid to facilitate school desegregation.

Although racist attitudes did not change overnight, the cultural changes brought on by the civil rights movement laid the groundwork for the creation of an integrated society. The Motown sound developed by Berry Gordy Jr. in the 1960s both reflected and furthered this change. Gordy believed that by coaching talented but unpolished Black artists, he could help them become more acceptable to mainstream culture. He hired a professional to head an in-house finishing school, teaching his acts how to move gracefully, speak politely, and use proper posture (Michigan Rock and Roll Legends). Gordy’s commercial success with gospel-based pop acts such as the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, and Martha and the Vandellas reflected the extent of racial integration in the mainstream music industry. Gordy’s most successful act, the Supremes, achieved 12 No. 1 singles on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

Musical Influences on Culture

Although pop music is often characterized as a predominantly negative influence on society, particularly in terms of its impact on youth culture, it also has positive effects on culture. Many artists in the 1950s and 1960s pushed the boundaries of socially acceptable behavior with sexually charged movements and androgynous appearances. Without these precedents, acts like the Rolling Stones or David Bowie might never have made the transition into mainstream success.

On the other hand, over the past 50 years, critics have blamed rock and roll for juvenile delinquency, heavy metal for increased teenage aggression, and gangsta rap for a rise in gang warfare among young urban males. One recent study claimed that youths who listen to music with sexually explicit lyrics are more likely to have sex at an early age, stating that exposure to lots of sexually degrading music gives teens “a specific message about sex (MSNBC, 2006).” In addition to its effects on youth culture, popular music has contributed to shifting cultural values regarding race, morality, and gender.

Race

As the music of Chuck Berry and Little Richard gained popularity among White teens in the United States during the 1950s, most of the new rock acts were signed to independent labels, and larger companies such as RCA started losing their share of the market.

To capitalize on the public’s enthusiasm for rock and roll and prevent further potential profits from being lost, major record companies signed White artists to cover the songs of Black artists. The companies often censored the songs for the mainstream market by removing any lyrics that referenced sex, alcohol, or drugs. Pat Boone gained popularity by releasing songs originally sung by artists such as Fats Domino, the El Dorados, Little Richard, and Big Joe Turner. Releasing a cover of a Black performer’s song by a White performer became known as hijacking a hit, and this practice often left Black artists signed to independent labels struggling financially. Because large companies such as RCA could widely promote and distribute their records, six of Boone’s recordings reached the No. 1 spot on the Billboard chart—their records frequently outsold the original versions. Many White artists and producers would also take writing credit for the songs they covered and would buy the rights to songs from Black writers without giving them royalties or songwriting credit. This practice fueled racism within the music industry. Independent record producer Danny Kessler of Okeh Records said, “The odds for a black record to crack through were slim. If the black record began to happen, the chances were that a white artist would cover it—and the big stations would play the white version…. There was a color line, and it wasn’t easy to cross (Szatmary).”

Although cover artists profited from the work of Black R&B singers, they also occasionally helped promote the original recordings. Many teenagers who heard covers on mainstream radio stations sought out the original artists’ versions, increasing sales and prompting Little Richard to refer to Pat Boone as “the man who made me a millionaire (Crane, 2005).” Benefiting from covers also worked both ways. In 1962, soul singer Ray Charles covered Don Gibson’s hit “I Just Can’t Stop Loving You,” which became a hit on country and western charts and furthered mainstream acceptance of Black musicians. Other Black artists to cover hits by White performers included Otis Redding, who performed the Rolling Stones’ hit “Satisfaction,” and Jimi Hendrix, who covered Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower.”

Stolen Rhythms: How Major Labels Silenced Black Artists’ Success

Releasing cover versions of hit songs became a fairly standard practice before the 1950s, as songwriters and producers found it advantageous to have as many artists as possible record their songs to maximize royalties. Several versions of the same song often appeared in the music charts at the same time. However, the practice acquired racial connotations during the 1950s when larger music labels hijacked R&B hits, using their financial strength to promote the cover version at the expense of the original recording, which often exploited Black talent. As a result, many 1950s R&B artists lost out on royalties.

Two contemporary Black performers who fell victim to this practice were R&B singer LaVern Baker and blues singer Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. The pop singer Baker had signed with the small-time label Atlantic Records. Because her songs appealed to mainstream audiences, industry giant Mercury Records took full advantage of this. When Baker released her 1955 hit “Tweedle Dee,” Mercury immediately put out its version, a note-for-note cover sung by White pop singer Georgia Gibbs. Atlantic could not match Mercury’s marketing budget, and Gibbs’s version outsold Baker’s recording, causing her to lose an estimated $15,000 in royalties (Parales, 1997).

Around the same time, Arthur Crudup produced hits such as “So Glad You’re Mine,” “Who’s Been Foolin’ You,” “That’s All Right,” and “My Baby Left Me,” which all found themselves subsequently released by performers such as Elvis Presley, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Rod Stewart for huge financial gain. Crudup’s songs made everybody rich—except him. This realization caused him to quit playing altogether in the late 1950s. A later attempt to collect back royalties proved unsuccessful (Stanton, 1998). Baker filed a lawsuit to revise the Copyright Act of 1909, making it illegal to copy an arrangement verbatim without permission. The lawsuit was unsuccessful, and Gibbs continued to cover Baker’s songs (Dahl).

Morality

Elvis Presley burst onto the rock and roll scene in the mid-1950s, alarming many conservative parents of teenagers across the United States. With his gyrating hips and sexually suggestive body movements, they viewed Presley as a threat to the moral well-being of young women. Television critics denounced his performances as vulgar, and on a 1956 appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, cameras filmed him only from the waist up. One critic for the New York Daily News wrote that popular music “has reached its lowest depths in the ‘grunt and groin’ antics of one Elvis Presley (Collins, 2002).” Despite the critics’ opinions, Presley immediately gained a fan base among teenage audiences, particularly adolescent girls, who frequently broke into hysterics at his concerts. Rather than tone down his act, Presley defended his movements as manifestations of the music’s rhythm and beat and continued to gyrate on stage. Liberated from the constraints imposed by morality watchdogs, Presley set a precedent for future rock and roll performers and marked a major transition in popular culture.

In addition to decrying raunchy onstage performances by rock and roll artists, moralists in the conservative Eisenhower era objected to the sexually suggestive lyrics found in original rock and roll songs. Big Joe Turner’s version of “Shake, Rattle, and Roll” used sexual phrases and referred to the bedroom, while Little Richard’s original version of “Tutti Frutti” contained the phrase “tutti frutti, loose booty (Hall & Hall, 2006).” Although many of these lyrics later became sanitized for the cover versions rereleased to mainstream White audiences, many people still thought that rock and roll threatened the morality of the country.

Ironically, many of the controversial key figures in the rock and roll era came from extremely religious backgrounds. Presley served as a member of the evangelical First Assembly of God Church, where he acquired his love of gospel music (History Of Rock). Similarly, Ray Charles absorbed gospel influences from his local Baptist church (Walk of Fame). Jerry Lee Lewis came from a strict Christian background and often struggled to reconcile his religious beliefs with the moral implications of the music he created. During a recording session in 1957, Lewis argued with manager Sam Phillips that the hit song “Great Balls of Fire” sounded too “sinful” for him to record (History, 1957). The religious backgrounds of the rock and roll pioneers both influenced and challenged moral norms. When Ray Charles recorded “I Got a Woman” in 1955, he reworded the gospel tune “Jesus Is All the World to Me,” drawing criticism that he had made a sacrilegious song. Despite the objections, Charles’s style caught on with other musicians, and his experimentation with merging gospel and R&B resulted in the birth of soul music.

Gender

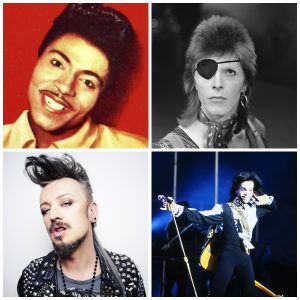

While Presley revolutionized people’s notions of sexual freedom and expression, other performers began changing cultural norms regarding gender identity. Dressed in flamboyant clothing with a pompadour hairstyle and makeup, Little Richard delivered an exotic, androgynous performance that blurred traditional gender boundaries and shocked 1950s audiences with his blatant campiness. Between his wild onstage antics, bisexual tendencies, and love of post-concert orgies, the self-proclaimed “King and Queen of Rock and Roll” challenged many social conventions of the time (Buckley, 2003). Little Richard’s flamboyant, gender-bending appearance challenged norms to such outrageous extremes that 1950s audiences did not take him seriously. They considered him an entertainer whose androgynous look bore no relevance to the real world. However, Richard paved the way for future entertainers to shift cultural perceptions of gender. Later musicians such as David Bowie, Prince, and Boy George adopted his outrageous style, frequently appearing on stage wearing glittery costumes and heavy makeup. The popularity of these 1970s and 1980s pop idols, along with other gender-bending performers such as Annie Lennox and Michael Jackson, helped make androgyny more acceptable in mainstream society.