7.4 Radio’s Impact on Culture

Since its inception, radio has had an immense impact on American culture. Entire genres of music that audiences now take for granted, such as country and rock, owe their popularity and even existence to early radio programs that publicized new forms of artistic expression.

A New Kind of Mass Media

Mass media, such as newspapers, had thrived for years before the advent of radio. Audiences initially considered the radio a kind of disembodied newspaper. Although this idea provided early proponents with a valuable and familiar way to think about radio, it underestimated the medium’s power. Newspapers had the potential to reach a broad audience, but radio had the potential to reach almost everyone simultaneously. Neither illiteracy nor even a busy schedule impeded the radio’s success—one could now perform an activity and listen to the radio at the same time. This unprecedented reach made radio an instrument of social cohesion as it brought together members of different classes and backgrounds to experience the world as a nation.

Radio programs reflected this nationwide cultural aspect of radio. Vox Pop, a show based initially on person-in-the-street interviews, attempted to quantify the United States’ growing mass culture. Beginning in 1935, the program billed itself as an unrehearsed “cross-section of what the average person knows” by asking random people an assortment of questions. Many modern television shows still employ this format, not only for viewers’ amusement and information, but also as an attempt to encapsulate national culture (Loviglio, 2002). Vox Pop functioned on a cultural level as an acknowledgment of radio’s entrance into people’s private lives, making them public (Loviglio, 2002).

Radio news offered more than just a quick way to find out about events; it provided a way for U.S. citizens to experience events with the same emotions. During the 1937 Ohio and Mississippi River floods, radio brought the voices of those who suffered, as well as the voices of those who fought the rising tides. A West Virginia newspaper explained the strengths of radio in providing emotional voices during such crises: “Thanks to radio…the nation as a whole has had its nerves, its heart, its soul exposed to the needs of its unfortunates…We are a nation that is integrated and interdependent. We are ‘our brother’s keeper (Brown).”

Radio’s presence in the home also heralded the evolution of consumer culture in the United States. In 1941, two-thirds of radio programs carried advertising. Radio allowed advertisers to sell products to a captive audience. This kind of mass marketing ushered in a new age of consumer culture (Cashman).

The Night Radio Unleashed Panic: Orson Welles and the War of the Worlds

During the 1930s, the aftermath of Orson Welles’s notorious War of the Worlds broadcast demonstrated the power of radio and its significant social influence. On Halloween night in 1938, radio producer Orson Welles told listeners of the Mercury Theatre on the Air that his players would treat them to an original adaptation of H. G. Wells’s classic science fiction novel of alien invasion, War of the Worlds. The adaptation began like a regular music show, only to be interrupted by a news flash reporting an alien invasion. Many listeners had tuned in late and did not hear the disclaimer, and the realism of the adaptation led them to believe aliens had invaded the country.

According to some estimates, an impressive 6 million people listened to the show, with an astonishing 1.7 million believing the account to be truthful (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). Some listeners called loved ones to say goodbye or ran into the street armed with weapons to fight off the invading Martians of the radio play (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). In Grover’s Mill, New Jersey—where the supposed invasion began—some listeners reported nonexistent fires and fired at a water tower, mistaking it for a Martian landing craft. One listener drove through his garage door in a rush to escape the area. Two Princeton University professors spent the night searching for the meteorite that had supposedly preceded the invasion (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). As calls came to local police stations, officers explained that they felt equally concerned about the problem (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). Although the story of the War of the Worlds broadcast may seem humorous in retrospect, the event left a lasting trauma on those who believed it. The program fooled individuals from every education level and walk of life, despite the producers’ warnings before, during the intermission, and after the program (Lubertozzi & Holmsten, 2005). This event revealed the unquestioning faith that many Americans had in radio. This event demonstrated the power of radio’s intimate communication style during the 1930s and 1940s.

Radio and the Development of Popular Music

Radio’s impact on music remains one of its most enduring legacies. Before the advent of radio, most popular songs would spread through piano sheet music or word of mouth. This necessarily limited the types of music that could gain national prominence. Although recording technology had also emerged several decades before radio, music played live over the radio sounded better than it did when played on a record at home. Live music performances thus became a staple of early radio. Many performance venues had their radio transmitters to broadcast live shows—for example, Harlem’s Cotton Club broadcast performances that CBS picked up and broadcast nationwide.

Radio networks mainly played swing jazz, giving the bands and their leaders a widespread audience. Popular bandleaders, including Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey, and their jazz bands gained national fame through their radio performances. In contrast, a host of other jazz musicians flourished as radio made the genre increasingly popular nationwide (Wald, 2009). National networks also played classical music. Often presented in an educational context, this programming had a different tenor than did dance-band programming. NBC promoted the genre through shows such as Music Appreciation Hour, which sought to educate both young people and the general public on the nuances of classical music (Howe, 2003). It established the NBC Symphony Orchestra, a 92-piece ensemble under the direction of the renowned conductor Arturo Toscanini. The orchestra delivered its first performance in 1937 and became so popular that Toscanini stayed on as conductor for 17 years (Horowitz, 2005). The Metropolitan Opera also enjoyed great popularity; its broadcasts in the early 1930s had an audience of 9 million listeners (Horowitz, 2005).

Regional Sounds Take Hold

The promotional power of radio also gave regional music an immense boost. Local stations often carried their programs featuring the popular music of the area. Stations such as Nashville, Tennessee’s WSM played early country, blues, and folk artists. The history of this station illustrates how radio—and its diverse range of broadcasting—created new perspectives on American culture. In 1927, WSM’s program Barn Dance, which featured early country music and blues, followed an hour-long program of classical music. George Hay, the host of Barn Dance, used the juxtaposition of classical and country genres to spontaneously rename the show: “For the past hour we have been listening to music taken largely from Grand Opera, but from now on we will present ‘The Grand Ole Opry (Kyriakoudes).’” NBC picked up the program for national syndication in 1939. It still broadcasts today, making it currently one of the longest-running radio programs of all time.

Shreveport, Louisiana’s KWKH aired an Opry-type show called Louisiana Hayride. This program propelled stars such as Hank Williams into the national spotlight. Country music, formerly a mix of folk, blues, and mountain music, became seen as a suitable genre for national audiences through his show. Without programs that featured these country and blues artists, Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash would not have become national stars, and country music may not have risen to become a popular genre (DiMeo, 2010).

In the 1940s, other Southern stations also began playing rhythm and blues records recorded by Black artists. Artists such as Wynonie Harris, famous for his rendition of Roy Brown’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” received airtime when White disc jockeys tried to imitate the sound of Black Southern musicians (Laird, 2005). During the late 1940s, Black individuals owned and operated both Memphis, Tennessee’s WDIA and Atlanta, Georgia’s WERD. These disc jockeys often provided a measure of community leadership at a time when few Black individuals held powerful positions (Walker).

Radio’s Lasting Influences

Radio technology changed the way that musicians performed popular music. Due to the use of microphones, audiences could hear vocalists more clearly over the band, enabling singers to utilize a wider vocal range and create more expressive styles. This innovation led to singers becoming an integral part of popular music’s image. The use of microphones similarly allowed individual musicians to perform solos or lead parts, a practice less encouraged before the advent of radio. Radio’s exposure also led to more rapid turnover in popular music. Before the advent of radio, jazz bands played the same arrangements for several years without them becoming stale, but as radio broadcasts reached a broad audience, musicians had to produce new arrangements and songs at a more rapid pace to keep up with changing tastes (Wald).

The spotlight of radio allowed the personalities of artists to come to the forefront of popular music, giving them newfound notoriety. Phil Harris, the bandleader from the Jack Benny Show, became the star of his program. Other famous musicians used radio talent shows to gain fame. Popular programs such as Major Bowes and His Original Amateur Hour featured unknown entertainers trying to gain fame through exposure to the show’s large audience. Major Bowes used a gong to usher bad performers offstage, often contemptuously dismissing them. However, not all performers struck out; successful singers such as Frank Sinatra debuted on the program (Sterling & Kitross).

Television, much like modern popular music, owes a significant debt to the Golden Age of Radio. Major radio networks, such as NBC, ABC, and CBS, became—and remain—major forces in television, and their programming decisions for radio laid the groundwork for the development of television. Actors, writers, and directors who worked in radio transferred their talents into the world of early television, using the successes of radio as their models.

Radio and Politics

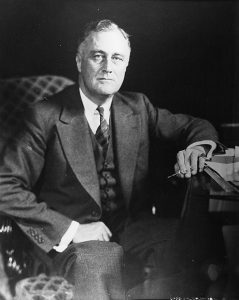

Over the years, radio has had a considerable influence on the political landscape of the United States. In the past, government leaders relied on radio to convey messages to the public, such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “fireside chats.” The government also utilized radio as a means to disseminate propaganda during World War II. The War Department established a Radio Division in its Bureau of Public Relations as early as 1941. Programs such as the Treasury Hour used radio drama to raise revenue through the sale of war bonds, but other government efforts took a decidedly political turn. The federal Office of Facts and Figures (OFF) funded Norman Corwin’s This Is War! to garner support for the war effort directly. It featured programs that prepared listeners to make personal sacrifices—including death—to win the war. The program also featured direct political content, declaring the New Deal as successful and bolstering Roosevelt’s image through comparisons with Lincoln (Horten).

The Original Airwaves Influencer: FDR’s Masterclass in Radio Politics

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-era radio talks, or “fireside chats,” remain one of the most famous uses of radio in politics. While governor of New York, Roosevelt had utilized radio as a political tool, so he quickly adopted it to explain the unprecedented actions his administration would take to address the economic fallout of the Great Depression. His first speech took place only one week after his inauguration. Roosevelt had closed all of the banks in the country for four days while the government dealt with a national banking crisis, and he used the radio to explain his actions directly to the American people (Grafton, 1999).

Roosevelt’s first radio address set a distinct tone as he employed informal speech in the hopes of inspiring confidence in the American people and of helping them stave off the kind of panic that could have destroyed the entire banking system. Roosevelt understood both the intimacy of radio and its assertive outreach (Grafton, 1999). He was thus able to strike a balance between a personal tone and a message intended for millions of people. This relaxed approach inspired a CBS executive to name the series the “fireside chats (Grafton, 1999).”

Roosevelt delivered a total of 27 of these 15- to 30-minute-long addresses to estimated audiences of 30 million to 40 million people, then a quarter of the U.S. population (Grafton, 1999). Roosevelt’s use of radio served as both a testament to his skills and savvy as a politician and a demonstration of the power and ubiquity of radio during this period. At the time, no other form of mass media could have had the same effect.

Indeed, the government has used radio for its purposes. Still, it has had an even greater impact on politics by serving “the ultimate arena for free speech (Davis & Owen, 1998).” Such infamous radio firebrands as Father Charles Coughlin, a Roman Catholic priest whose radio program opposed the New Deal, criticized Jews, and supported Nazi policies, aptly demonstrated this capability early in radio’s history (Sterling & Kitross). In recent decades, radio has supported the careers of notable politicians, including former U.S. Senator Al Franken of Minnesota, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, and presidential aspirant Fred Thompson. Talk show hosts have gained significant political influence. Before he died in 2021, some viewed conservative talk show host Rush Limbaugh as the de facto leader of the Republican Party (Halloran, 2009).

The Importance of Talk Radio

Modern talk radio programs exemplify a significant contemporary convergence of radio and politics. The genre that gained popularity in the 1980s features a host who takes callers and discusses a variety of topics. Talk radio hosts gain and retain their listeners by sheer force of personality, and some say shocking or insulting things to convey their message. These hosts range from conservative radio hosts, such as Sean Hannity, to so-called shock jocks, like Howard Stern.

Repeal of the Fairness Doctrine

While talk radio first emerged during the 1920s, its transformation into a contemporary cultural and political force occurred during the mid-to-late 1980s, following the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine (Cruz, 2007). This doctrine, established in 1949, required any station broadcasting a political point of view over the air to allow equal time to all reasonable dissenting views. Despite its noble intentions of safeguarding public airwaves for diverse views, the doctrine had long attracted dissent. Opponents of the Fairness Doctrine claimed that it had a chilling effect on political discourse, as broadcasters, rather than risk government intervention, avoided programs that some may find divisive or controversial (Cruz, 2007). In 1987, the FCC, under the Reagan administration, repealed the regulation, setting the stage for a boom in AM talk radio. By 2004, the number of talk radio stations had increased 17-fold (Anderson, 2005).

The end of the Fairness Doctrine allowed stations to broadcast programs without worrying about finding an opposing point of view to balance the host’s stated opinions. Radio hosts representing all points of the political spectrum could say anything that they wanted to—within FCC limits—without fear of rebuttal. Chapter 14, “Ethics of Mass Media,” will delve into the topics of media bias and its consequences in greater detail.

The Revitalization of AM

The migration of music stations to the FM spectrum during the 1960s and 1970s created a significant amount of space on the AM band for talk shows. With the Fairness Doctrine no longer a hindrance, these programs slowly gained notoriety during the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1998, talk radio hosts railed against a proposed congressional pay increase, and their listeners became incensed. House Speaker Jim Wright received a deluge of faxes protesting it from irate listeners from stations all over the country (Douglas). Ultimately, Congress canceled the pay increase, and various print outlets acknowledged the influence of talk radio on the decision. Propelled by events such as these, talk radio stations increased from approximately 200 in the early 1980s to more than 850 by 1994 (Douglas).

From Aliens to Airwaves: The Unlikely Reign of Paranormal Talk Radio

Although political programs unquestionably dominate AM talk radio, that dial also hosts a type of show that some radio listeners may have never experienced, late at night on AM radio, a program airs that features stories about ghosts, alien abductions, and fantastic creatures. It’s not a fictional drama program, however, but instead a call-in talk show called Coast to Coast AM. In 2006, this unlikely success ranked among the top 10 AM talk radio programs in the nation—a remarkable feat, considering its 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. time slot and unconventional format (Vigil, 2006).

Initially started by host Art Bell in the 1980s, Coast to Coast AM focuses on topics that mainstream media outlets rarely treat seriously. Regular guests include ghost investigators, psychics, Bigfoot biographers, alien abductees, and deniers of the moon landing. The guests take calls from listeners who ask questions or talk about their own paranormal experiences or theories.

Coast to Coast AM’s current host, George Noory, has continued the show’s format. In some areas, its ratings have even exceeded those of Rush Limbaugh’s (Vigil, 2006). For a late-night show, ratings of this caliber do not often occur. The success of Coast to Coast serves as a continuing testament to the diversity and unexpected potential of radio (Vigil, 2006).

On-Air Political Influence

As talk radio’s popularity grew during the early 1990s, it quickly became an outlet for political ambitions. In 1992, nine talk show hosts ran for U.S. Congress. By the middle of the decade, it had become common for many former or failed politicians to attempt to use the format as a means to enter politics. Former California Governor Jerry Brown and former New York Mayor Ed Koch both began their political careers in the mid-1990s and went on to host AM talk shows (Annenberg Public Policy Center, 1996). Both conservatives and liberals widely agree that conservative hosts dominate the AM talk radio format. Many talk show hosts followed in the steps of Rush Limbaugh, who began his popular and profitable program one year after the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine and lasted until his passing.

During the 2000s, AM talk radio continued to build. Hosts such as Michael Savage, Sean Hannity, and Bill O’Reilly furthered the trend of popular conservative talk shows. Still, liberal hosts also became popular through the short-lived Air America network, which closed abruptly in 2010 amid financial concerns (Stelter, 2010). Although the network did not succeed, it provided a platform for such hosts as MSNBC TV news host Rachel Maddow and Minnesota Senator Al Franken. Other liberal hosts such as Bill Press and Ron Reagan, son of President Ronald Reagan, have also found success in the AM political talk radio field (Stelter, 2010). Despite these successes, liberal talk radio often cannot sustain itself (Hallowell, 2010). To some, the failure of Air America confirms conservatives’ domination of AM radio. In response to the conservative dominance of talk radio, many prominent liberals, including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, have advocated for reinstating the Fairness Doctrine, which would require stations to offer equal time to contrasting opinions (Stotts, 2008).

Freedom of Speech and Radio Controversies

While the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution gives radio personalities the freedom to say nearly anything they want on the air without fear of prosecution (except in cases of obscenity, slander, or incitement of violence, which Chapter 15 “Media and Government” will discuss in greater detail), it does not protect them from being fired from their jobs when their controversial comments create a public outrage. Many talk radio hosts, such as Howard Stern, push the boundaries of acceptable speech to engage listeners and boost ratings. Still, sometimes radio hosts push too far, unleashing a storm of controversy.

Making (and Unmaking) a Career out of Controversy

Talk radio host Howard Stern has built his career on creating controversy, despite multiple fines for indecency issued by the FCC, Stern remains one of the highest-paid and most popular talk radio hosts in the United States. Stern’s radio broadcasts often feature scatological or sexual humor, creating an atmosphere where “anything goes.” Because his on-air antics frequently generate controversy that can jeopardize advertising sponsorships and drive away offended listeners, in addition to risking fines from the FCC, Stern has a history of uneasy relationships with the radio stations that employ him. To free himself from conflicts with station owners and sponsors, in 2005, Stern signed a contract with Sirius Satellite Radio, a private company exempt from FCC regulation, allowing him to continue broadcasting his show without fear of censorship.

Other radio hosts who have gotten themselves in trouble with poorly considered on-air comments have not shared his luck. In April 2007, Don Imus, host of the long-running Imus in the Morning, received a suspension for racist and sexist comments made about the Rutgers University women’s basketball team (MSNBC, 2007). Though he publicly apologized, the scandal continued to draw negative attention in the media, and CBS canceled his show to avoid further unfavorable publicity and the withdrawal of advertisers. Though he returned to the airwaves in December of that year with a different station, the experience resulted in a significant setback for Imus’s career and his public image. Similarly, syndicated conservative talk show host Dr. Laura Schlessinger ended her radio show in 2010 due to pressure from radio stations and sponsors after her repeated use of a racial epithet on a broadcast incited a public backlash (MSNBC, 2007).

In the digital age, Joe Rogan has emerged as a similarly influential figure, navigating and often generating controversy through his podcast, The Joe Rogan Experience. With an audience estimated to be in the tens of millions per episode, and a reported exclusive licensing deal with Spotify valued at over $200 million, Rogan’s platform is immense. Like Stern’s move to satellite radio, Rogan’s transition to Spotify allowed him to operate outside the traditional broadcast regulations and advertiser pressures that can constrain terrestrial radio hosts. His long-form interviews, covering a vast range of topics from science and politics to conspiracy theories, often feature controversial guests and discussions that have drawn criticism for spreading misinformation or promoting divisive viewpoints. Despite these controversies, including petitions for his removal from Spotify and artists boycotting the platform, Rogan’s immense listenership and the direct relationship he fosters with his audience have largely insulated his career from the severe setbacks faced by traditional radio hosts like Imus or Schlessinger. This demonstrates a significant shift in how influential figures can build and sustain careers, leveraging direct digital distribution to bypass traditional gatekeepers and their associated censorship and financial pressures.

In recent years, several personalities have faced termination due to controversial statements. A notable instance from July 2023 involved Don Geronimo, a Washington D.C. radio host, who was fired from WBIG “BIG 100” after making sexist remarks about a female sports reporter, Sharla McBride, during a broadcast from a Washington Commanders’ training camp. He referred to her as “Barbie girl” and questioned if she was a cheerleader, leading to widespread condemnation and his swift dismissal by iHeartMedia.

Another example from October 2023 saw Oklahoma City radio personality Ronnie Kay lose his job at KOMA 92.5. He was reportedly fired after an on-air comment regarding Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day where he stated, “I don’t know what indigenous means and I don’t care.” These incidents highlight that despite the evolving media landscape, radio hosts are still held accountable by their employers and the public for comments made on air, particularly when those comments are deemed offensive or disparaging.

As the examples of these talk radio hosts demonstrate, the issue of freedom of speech on the airwaves often gets complicated by the need for radio stations to make a profit. Outspoken or shocking radio hosts can draw in a large audience, attracting advertisers to sponsor their shows and generating revenue for their radio stations. Although the hosts may offend some listeners and deter them from tuning in, as long as they continue to attract advertising dollars, their employers usually allow the hosts to speak freely on the air. However, suppose a host’s behavior ends up sparking a significant controversy, causing advertisers to withdraw their sponsorship to avoid tarnishing their brands. In that case, the radio station will often fire the host and look for someone who can better sustain advertising partnerships. Radio hosts’ right to free speech does not compel their employer to give them the forum to exercise it. Popular hosts like Don Imus may find a home on the air again once the furor has died down, but radio hosts concerned about the stability of their careers should remember the practical limits on their freedom of speech.