8.2 The History of Movies

The movie industry originated in the early 19th century through a series of technological developments: the creation of photography, the discovery of the illusion of motion by combining individual still images by luminaries such as Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey, and the study of human and animal locomotion. The history presented here begins at the culmination of these technological developments, where the idea of the motion picture as an entertainment industry first emerged. Since then, the industry has seen extraordinary transformations, some driven by the artistic visions of individual participants, some by commercial necessity, and still others by accident. The complexity of cinema’s history prohibits this book from mentioning every important innovator and movement. Nonetheless, this chapter will help readers understand the broad arc of the development of a medium that has captured the imaginations of audiences worldwide for over a century.

The Beginnings: Motion Picture Technology of the Late 19th Century

While the experience of watching movies on smartphones may seem like a drastic departure from the communal nature of modern film viewing, in some ways, the small-format, single-viewer screen display recaptures the early roots of film. In 1891, inventor Thomas Edison, along with his assistant William Dickson, introduced the kinetoscope. This device would become the predecessor to the motion picture projector. The kinetoscope consisted of a cabinet with a window through which individual viewers could experience the illusion of a moving image (Gale Virtual Reference Library, British Movie Classics). A perforated celluloid film strip with a sequence of pictures on it was rapidly spooled between a light bulb and a lens, creating the illusion of motion (Britannica). The images viewers could see in the kinetoscope captured events and performances that Edison staged at his film studio in East Orange, New Jersey, especially for the Edison kinetograph (the camera that produced kinetoscope film sequences): circus performances, dancing women, cat fights, boxing matches, and even a man sneezing (Robinson, 1994).

As the kinetoscope gained popularity, the Edison Company began installing machines in hotel lobbies, amusement parks, and penny arcades. Soon, kinetoscope parlors—where customers could pay around 25 cents for admission to a bank of machines—opened around the country. However, when friends and collaborators suggested that Edison find a way to project his kinetoscope images for audience viewing, he refused, claiming that such an invention would make less profit (Britannica).

Because Edison hadn’t secured an international patent for his invention, variations of the kinetoscope soon appeared throughout Europe. This new form of entertainment achieved instant success, and many mechanics and inventors, seeing an opportunity, began toying with methods of projecting moving images onto a larger screen. However, the invention of two brothers, Auguste and Louis Lumière, who were manufacturers of photographic goods in Lyon, France, saw the most commercial success. In 1895, the brothers patented the cinématographe (the origin of the term cinema), a lightweight film projector that also functioned as a camera and printer. Unlike the Edison kinetograph, the cinématographe’s lightweight design made outdoor filming much easier. Over the years, the brothers used the camera to create well over 1,000 short films, most of which depicted scenes from everyday life.

Believing that audiences would get bored watching scenes that they could just as easily observe on a casual walk around the city, Louis Lumière claimed that the cinema was “an invention without a future (Menand, 2005),” but a demand for motion pictures grew at such a rapid rate that soon representatives of the Lumière company traveled throughout Europe and the world, showing half-hour screenings of the company’s films. While cinema initially competed with other popular forms of entertainment—such as circuses, vaudeville acts, theater troupes, magic shows, and many others—it would eventually supplant these various entertainments as the main commercial attraction (Menand, 2005). Within a year of the Lumières’ first commercial screening, competing film companies offered moving-picture acts in music halls and vaudeville theaters across Great Britain. In the United States, the Edison Company, having purchased the rights to an improved projector that they called the Vitascope, held their first film screening in April 1896 at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in Herald Square, New York City.

Modern audiences may struggle to comprehend the film’s profound impact on its original viewers. However, the sheer volume of reports about the early audience’s disbelief, delight, and even fear at what they witnessed suggests that many people became overwhelmed when viewing a film. Spectators gasped at the realistic details in films such as Robert Paul’s Rough Sea at Dover, and at times, people panicked and tried to flee the theater during films in which trains or moving carriages sped toward the audience (Robinson). Even the public’s perception of cinema as a medium differs considerably from the contemporary understanding; the moving image, to them, improved upon the photograph—a familiar medium for viewers—and explains why the earliest films documented events in brief segments but did not attempt to tell stories. During this “novelty period” of cinema, the phenomenon of the film projector itself interested audiences, so vaudeville halls advertised the kind of projector they used (for example “The Vitascope—Edison’s Latest Marvel”) (Balcanasu, et. al.), rather than the names of the films (Britannica Online).

By the close of the 19th century, as public excitement over the moving picture’s novelty gradually wore off, filmmakers began to experiment with the medium’s possibilities as a means of expression in itself (not simply as a tool for documentation, analogous to the camera or the phonograph). Technical innovations allowed filmmakers like Parisian cinema owner Georges Méliès to experiment with special effects that produced seemingly magical transformations on screen: flowers turned into women, people disappeared with puffs of smoke, a man appeared where a woman had just been standing, and other similar tricks (Robinson).

Not only did Méliès, a former magician, invent the “trick film,” which producers in England and the United States began to imitate, but he also transformed cinema into the narrative medium it is today. Whereas filmmakers had previously only created single-shot films that lasted a minute or less, Méliès began combining these short films to create longer stories. His 30-scene Trip to the Moon (1902), a film based on Jules Verne‘s novel, likely stands as one of the most widely seen productions in cinema’s first decade (Robinson). However, Méliès never developed his technique beyond treating the narrative film as a staged theatrical performance; his camera, representing the vantage point of an audience facing a stage, never moved during the filming of a scene. In 1912, Méliès released his last commercially successful production, The Conquest of the Pole. From then on, he lost audiences to filmmakers who experimented with more sophisticated techniques (Encyclopedia of Communication and Information).

The Nickelodeon Craze (1904–1908)

Edwin S. Porter, a projectionist and engineer for the Edison Company, broke with the stage-like compositions of Méliès-style films in his 12-minute film, The Great Train Robbery (1903). The film incorporated elements of editing, camera pans, rear projections, and diagonally composed shots that produced a continuity of action. Not only did The Great Train Robbery establish the realistic narrative as a standard in cinema, but it also became the first major box-office hit. Its success paved the way for the growth of the film industry, as investors, recognizing the motion picture’s great moneymaking potential, began opening the first permanent film theaters around the country.

Known as nickelodeons because of their five-cent admission charge, these early motion picture theaters, often housed in converted storefronts, proved especially popular among the working class of the time, who couldn’t afford live theater. Between 1904 and 1908, around 9,000 nickelodeons appeared in the United States. The nickelodeon’s popularity established film as a mass entertainment medium (Dictionary of American History).

The “Biz”: The Motion Picture Industry Emerges

As demand for motion pictures grew, production companies emerged to meet it. At the peak of Nickelodeon’s popularity in 1910 (Britannica Online), approximately 20 major motion picture companies operated in the United States. However, heated disputes often broke out among these companies over patent rights and industry control, leading even the most powerful among them to fear fragmentation that would loosen their hold on the market (Fielding, 1967). Because of these concerns, the 10 leading companies—including Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, and others—formed the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC) in 1908. The MPPC served as a trade group that pooled the most significant motion picture patents and established an exclusive contract between these companies and the Eastman Kodak Company, which supplied film stock. Also known as “the Trust,” the MPPC attempted to standardize the industry and shut out competition through monopolistic control. Under the Trust’s licensing system, only licensed companies could participate in the exchange, distribution, and production of films at various levels of the industry. This shut-out tactic eventually backfired, leading the excluded, independent distributors to organize in opposition to the Trust (Britannica Online).

The Rise of the Feature

In these early years, theaters still ran single-reel films, which were typically 1,000 feet in length, allowing for approximately 16 minutes of playing time. However, companies began to import multiple-reel films from European producers around 1907, and the format gained widespread acceptance in the United States in 1912 with the release of Louis Mercanton’s highly successful Queen Elizabeth, a three-and-a-half reel “feature,” starring the French actress Sarah Bernhardt. As exhibitors began to show more features, as the term assigned to multiple-reel films, they discovered several advantages over the single-reel short. For one thing, audiences viewed these longer films as special events and were willing to pay more for admission. In addition, the popularity of the feature narratives meant features generally experienced longer runs in theaters than their single-reel predecessors (Motion Pictures). Additionally, the feature film gained popularity among the middle classes, who saw its length as analogous to the more “respectable” entertainment of live theater (Motion Pictures). Following the example of the French film d’art, U.S. feature producers often took their material from sources that would appeal to a wealthier and better-educated audience, such as histories, literature, and stage productions (Robinson).

As it turns out, the feature film contributed to the eventual downfall of the MPPC. The inflexible structuring of the Trust’s exhibition and distribution system made the organization resistant to change. When movie studio and Trust member Vitagraph began releasing features like A Tale of Two Cities (1911) and Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1910), the Trust compelled it to exhibit the films serially in single-reel showings to conform to industry standards. The MPPC also underestimated the appeal of the star system. This trend began when producers chose famous stage actors, such as Mary Pickford and James O’Neill, to play leading roles in their productions and to feature on their advertising posters (Robinson). Because of the MPPC’s inflexibility, independent companies exclusively capitalized on two significant trends of film’s future: single-reel features and star power. Today, few people recognize names like Vitagraph or Biograph. Still, the independents that outlasted them—Universal, Goldwyn (which would later merge with Metro and Mayer to form MGM), Fox (later 20th Century Fox), and Paramount (the later version of the Lasky Corporation)—have become industry juggernauts.

Hollywood

As moviegoing increased in popularity among the middle class and feature films began keeping audiences in their seats for more extended periods, exhibitors found a need to create more comfortable and richly decorated theater spaces to attract their audiences. These “dream palaces,” so called because of their often lavish embellishments of marble, brass, gilding, and cut glass, not only came to replace the nickelodeon theater but also created the demand that would lead to the Hollywood studio system. Some producers realized that they could only meet the growing demand for new work if they produced films on a regular, year-round basis. However, this proved impractical with the current system, which often relied on outdoor filming and shot footage predominantly in Chicago and New York—two cities whose weather conditions prevented outdoor filming for a significant portion of the year. Different companies attempted filming in warmer locations, such as Florida, Texas, and Cuba, but producers eventually found an ideal candidate: a small, industrial suburb of Los Angeles called Hollywood.

In addition, Thomas Edison’s aggressive enforcement of his motion picture patents through the Motion Picture Patents Company (the “Edison Trust”) significantly motivated early filmmakers to relocate. Seeking to operate outside the Trust’s restrictive and litigious control, independent producers migrated westward. This desire for creative and operational freedom from Edison’s monopoly was a key factor in establishing Hollywood, California, as the burgeoning center of the American film industry.

Hollywood proved to be an ideal location for many reasons. The location combined a temperate climate with year-round sun. In addition, the abundantly available land was relatively inexpensive, and the location provided close access to diverse topographies, including mountains, lakes, deserts, coasts, and forests. By 1915, more than 60 percent of U.S. film production was based in Hollywood (Britannica Online).

The Art of Silent Film

While commercial factors drove the development of narrative film, individual artists turned it into a medium of personal expression. The motion pictures of the silent era generally appear simplistic, acted out in overly animated movements to engage the eye, and accompanied by live music played by musicians in the theater, as well as written titles, to create a mood and narrate a story. Within the confines of this medium, one filmmaker in particular emerged to transform silent film into an art form and unlock its potential as a medium of serious expression and persuasion. D. W. Griffith, who entered the film industry as an actor in 1907, quickly transitioned to a directing role, where he worked closely with his camera crew to experiment with shots, angles, and editing techniques that could heighten the emotional intensity of his scenes. He found that by practicing parallel editing, in which a film alternates between two or more scenes of action, he could create an illusion of simultaneity. He could then heighten the tension of the film’s drama by alternating between cuts more and more rapidly until the scenes of action converged. Griffith employed this technique to significant effect in his controversial film, The Birth of a Nation, which will be discussed in greater detail in the next section. Other methods that Griffith employed to new effect included panning shots, through which he established a sense of scene and engaged his audience more fully in the experience of the film, and tracking shots, or shots that traveled with the movement of a scene (Motion Pictures), which allowed the audience—through the eye of the camera—to participate in the film’s action.

D.W. Griffith’s monumental 1916 film, Intolerance, ingeniously wove together four distinct stories, each set in a different historical period, to explore themes of prejudice and injustice across the ages. This ambitious project, undertaken largely as a response to the widespread criticism of the overt racism in his previous work, The Birth of a Nation, unfortunately resulted in significant financial losses for Griffith, consuming all the money earned from his earlier success and requiring substantial outside funding. Despite its artistic innovation, Intolerance was a commercial failure in its time, owed to its immense production costs and a complex narrative that was often misunderstood, particularly as the United States entered World War I shortly after its premiere. Its costly failure fundamentally shifted power dynamics within the burgeoning film industry, subsequently making directors more accountable to producers and paving the way for greater studio oversight.

MPAA: Combating Censorship

As film became an increasingly lucrative U.S. industry, prominent figures such as D. W. Griffith, the slapstick comedian and director Charlie Chaplin, and actors Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks grew extremely wealthy and influential. The public had conflicting attitudes toward stars and some of their extravagant lifestyles: on the one hand, they idolized celebrities and imitated them in popular culture, yet at the same time, they criticized them for representing a threat, both on and off screen, to traditional morals and social order. And much as it does today, the news media likes to sensationalize the lives of celebrities to sell stories. Comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, who worked alongside future icons Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, found himself at the center of one of the biggest scandals of the silent era. When Arbuckle hosted a marathon party over Labor Day weekend in 1921, one of his guests, model Virginia Rapp, was rushed to the hospital, where she later died. Reports of a drunken orgy, rape, and murder surfaced. Following World War I, the United States underwent significant social reforms, including the Prohibition era. Many feared that movies and their stars could threaten the moral order of the country. Because of the nature of the crime and the celebrity involved, those fears became inexplicably tied to the Arbuckle case (Motion Pictures). Even though autopsy reports ruled that Rapp had died from causes that Arbuckle could not have caused, the comedian still faced trial, where a jury acquitted him of manslaughter, though his career would never recover.

The Arbuckle affair and a series of other scandals only increased public fears about Hollywood’s impact. In response to this perceived threat, state and local governments increasingly tried to censor the content of films that depicted crime, violence, and sexually explicit material. Deciding that they needed to protect themselves from government censorship and to foster a more favorable public image, the major Hollywood studios organized in 1922 to form an association they called the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (now known as the Motion Picture Association, or MPA). Among other things, the MPA instituted a code of self-censorship for the motion picture industry. Today, the MPA operates a voluntary rating system, which means producers can voluntarily submit a film for review to receive a rating designed to alert viewers to the age appropriateness of a movie, while still protecting filmmakers’ artistic freedom (Motion Picture Association).

Silent Film’s Demise

In 1925, Warner Bros. sought to differentiate itself from its competitors as a small Hollywood studio seeking expansion opportunities. When representatives from Western Electric offered to sell the studio the rights to a new technology they called Vitaphone, a sound-on-disc system that had failed to capture the interest of any of the industry giants, Warner Bros. executives took a chance, predicting that the novelty of talking films might help them make a quick, short-term profit. Little did they anticipate that their gamble would not only establish them as a major Hollywood presence but also change the industry forever.

The pairing of sound with motion pictures had occurred before this point. Edison, after all, had commissioned the kinetoscope to create a visual accompaniment to the phonograph, and many early theaters had orchestra pits to provide musical accompaniment to their films. Even the smaller picture houses with lower budgets almost always had an organ or piano. When Warner Bros. purchased Vitaphone technology, it planned to use it to provide prerecorded orchestral accompaniment for its films, thereby increasing their marketability to smaller theaters that lacked their orchestra pits (Gochenour, 2000). In 1926, Warner debuted the system with the release of Don Juan, a costume drama accompanied by a recording of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra; the public responded enthusiastically (Motion Pictures). By 1927, after a $3 million campaign, Warner Bros. had wired more than 150 theaters in the United States, and it released its second sound film, The Jazz Singer, in which the actor Al Jolson improvised a few lines of synchronized dialogue and sang six songs. The film constituted a breakthrough. Audiences, hearing an actor speak on screen for the first time, became enchanted (Gochenour). While radio, a new and popular entertainment, had siphoned audiences away from the picture houses for some time, with the birth of the “talkie,” or talking film, audiences once again returned to the cinema in large numbers, lured by the promise of seeing and hearing their idols perform (Higham, 1973). By 1929, three-fourths of Hollywood films had some form of sound accompaniment, and by 1930, the silent movie had become a relic of the past (Gochenour).

From Fantasia to the Front Lines: Disney’s Animated War Machine

During World War II, the Walt Disney Studio played a significant and often surprising role in the American propaganda effort, leveraging its unique animation style and broad appeal to disseminate wartime messages. Faced with a drastic reduction in commercial film production due to the war, Disney turned its creative talents towards supporting the Allied cause. The studio produced a wide array of films, from morale-boosting shorts to instructional training videos and even overtly anti-Axis propaganda. Characters like Donald Duck and Goofy became unlikely wartime heroes, engaging audiences with humor while subtly (or not so subtly) promoting themes of patriotism, sacrifice, and the importance of war bonds. This collaboration showcased the power of popular culture to influence public sentiment and demonstrated Hollywood’s deep integration into national efforts during times of crisis.

These early Disney propaganda films served multiple purposes. Some, like the Academy Award-winning Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943), starring Donald Duck, satirized the enemy, depicting the absurdities and harsh realities of life under Nazi rule with a blend of dark humor and pointed criticism. Others, such as Education for Death: The Making of the Nazi (1943), adopted a more serious and chilling tone, illustrating the indoctrination of German youth into the Nazi ideology. Beyond direct propaganda, Disney also produced numerous training films for the military, explaining complex concepts or demonstrating proper procedures for soldiers, pilots, and sailors. These films, often featuring familiar characters or clear, simplified animation, proved highly effective in conveying vital information quickly and memorably.

The cultural impact of these Disney war films was profound. They reached millions of Americans, shaping perceptions of the enemy, reinforcing national unity, and preparing citizens for the sacrifices required by the war. For a studio primarily known for whimsical fairy tales and family entertainment, this foray into political and military messaging solidified animation’s versatility as a powerful communication tool.

“I Don’t Think We’re in Kansas Anymore”: Film Goes Technicolor

Although filmmakers could employ the techniques of tinting and hand-painting color in films for some time (Georges Méliès, for instance, used a crew to hand-paint many of his movies), neither method was suitable for large-scale projects. The hand-painting technique became impractical with the advent of mass-produced film, and the tinting process, which filmmakers discovered would interfere with the transmission of sound in cinema, was abandoned with the rise of the talkie. However, in 1922, Herbert Kalmus’s Technicolor company introduced a dye-transfer technique that allowed it to produce a full-length film, The Toll of the Sea, in two primary colors (Gale Virtual Reference Library). However, because they only used two colors, the appearance of The Toll of the Sea (1922), The Ten Commandments (1923), and other early Technicolor films did not appear very lifelike. By 1932, Technicolor had developed a three-color system that produced more realistic results. For the next 25 years, all major studios produced color films using this improved system. Disney’s Three Little Pigs (1933), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), and movies featuring live actors, such as MGM’s The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Gone with the Wind (1939), achieved early success using Technicolor’s three-color method.

Despite the success of certain color films in the 1930s, Hollywood, like the rest of the United States, was deeply affected by the Great Depression. The expenses of special cameras, crews, and Technicolor lab processing made color films impractical for studios trying to cut costs. Therefore, Technicolor would largely displace the black-and-white movie until the end of the 1940s (Motion Pictures in Color).

Rise and Fall of the Hollywood Studio

The spike in theater attendance that followed the introduction of talking films altered the economic structure of the motion picture industry, leading to some of the largest mergers in industry history. By 1930, eight studios produced 95 percent of all American films, and they continued to experience growth even during the Depression. The five most influential of these studios—Warner Bros., Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, RKO, 20th Century Fox, and Paramount—practiced vertical integration, meaning they controlled every part of the system related to their films, from production to release, distribution, and even exhibition. Because they owned theater chains worldwide, these studios controlled which movies exhibitors ran, and because they “owned” a stock of directors, actors, writers, and technical assistants by contract, each studio produced films of a particular character.

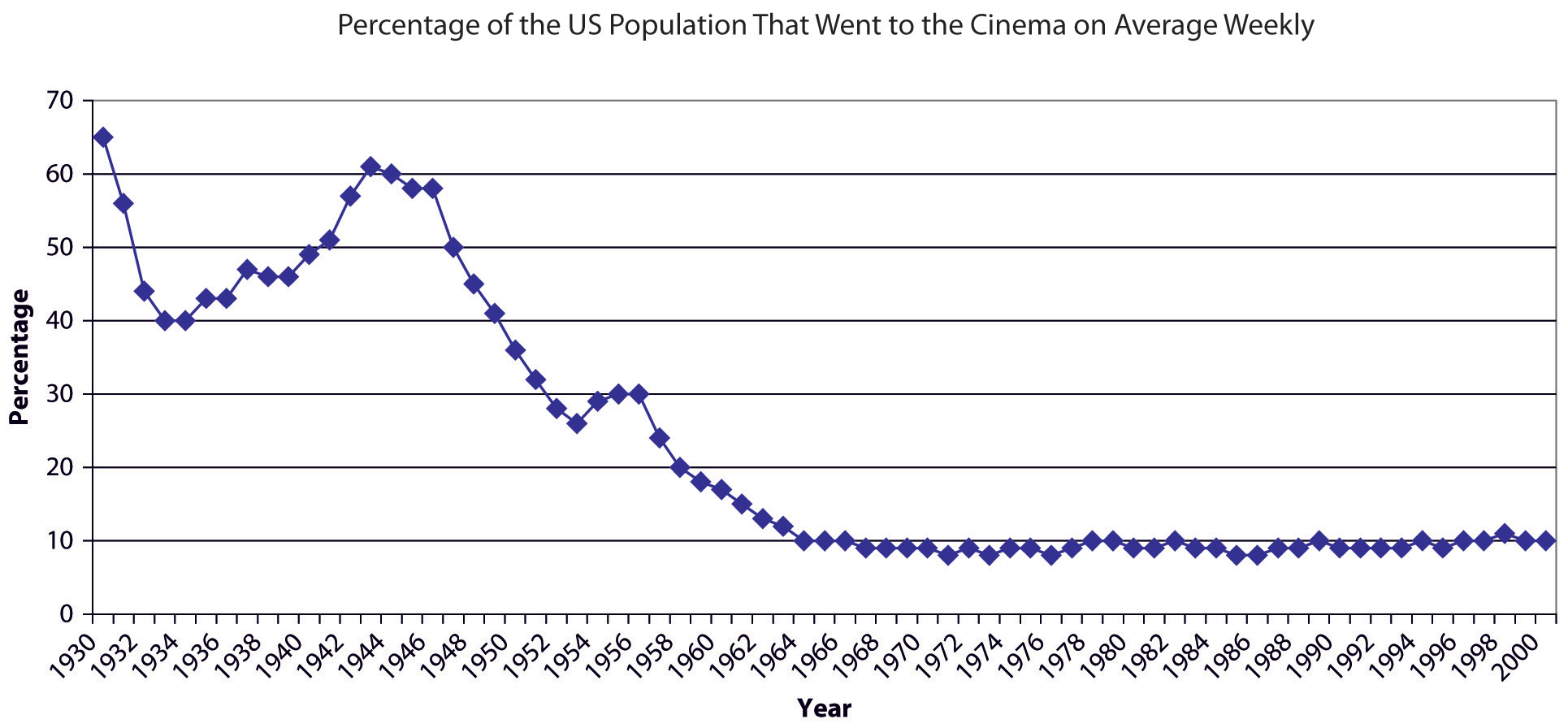

The late 1930s and early 1940s sometimes get referred to as the “Golden Age” of cinema, a time of unparalleled success for the movie industry; by 1939, film ranked as the 11th-largest industry in the United States, and during World War II, when the U.S. economy flourished, two-thirds of Americans attended the theater at least once a week (Britannica Online). Some of the most acclaimed movies in history were released during this period, including Citizen Kane and The Grapes of Wrath. However, postwar inflation, a temporary loss of key foreign markets, the advent of television, and other factors combined to bring that rapid growth to an end. In 1948, the case of the United States v. Paramount Pictures—mandating competition and forcing the studios to relinquish control over theater chains—dealt the final devastating blow from which the studio system would never recover. Control of the major studios reverted to Wall Street, where multinational corporations eventually absorbed the studios, and the powerful studio heads lost the influence they had held for nearly 30 years (Baers, 2000).

Post–World War II: Television Presents a Threat

While economic factors and antitrust legislation played key roles in the decline of the studio system, the advent of television represents the primary factor. Given the opportunity to watch “movies” from the comfort of their own homes, the millions of Americans who owned a television by the early 1950s began attending the cinema far less regularly than they had just a few years earlier (Motion Pictures). In an attempt to win back diminishing audiences, studios did their best to exploit the greatest advantages film held over television. For one thing, television could only broadcast in black and white in the 1950s, whereas the film industry had the advantage of color. While producing a color film still required a considerable budget in the late 1940s, a couple of changes occurred in the industry in the early 1950s that made color not only more affordable but also more realistic in its appearance. In 1950, as a result of antitrust legislation, Technicolor lost its monopoly on the color film industry, allowing other providers to offer more competitive pricing on filming and processing services. At the same time, Kodak introduced a multilayer film stock that enabled the use of more affordable cameras and produced higher-quality images. Kodak’s Eastman Color option became an integral component in converting the industry to color. In the late 1940s, studios released only 12 percent of their features in color; however, by 1954 (following the release of Kodak Eastman Color), more than 50 percent of movies featured color (Britannica Online).

Filmmakers also tried to capitalize on the sheer size and scope of the cinematic experience. With the release of the epic biblical film The Robe in 1953, 20th Century Fox introduced the method that nearly every studio in Hollywood would soon adopt: a technology that allowed filmmakers to squeeze a wide-angle image onto conventional 35-mm film stock, thereby increasing the aspect ratio (the ratio of a screen’s width to its height) of their pictures. This wide-screen format increased the immersive quality of the theater experience. Nonetheless, even with these advancements, movie attendance never again reached the record numbers it experienced in 1946, at the peak of the Golden Age of Hollywood (Britannica Online).

Mass Entertainment, Mass Paranoia: HUAC and the Hollywood Blacklist

The Cold War with the Soviet Union began in 1947, and with it came the widespread fear of communism, not only from the outside, but equally from within. To undermine this perceived threat, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) commenced investigations to locate communist sympathizers in America whom they suspected of conducting espionage for the Soviet Union. In the highly conservative and paranoid atmosphere of the time, Hollywood, the source of a mass-cultural medium, came under fire in response to fears that studios had embedded subversive, communist messages in films. In November 1947, Congress called more than 100 people in the movie business to testify before the HUAC about their and their colleagues’ involvement with communist affairs. Of those investigated, 10 in particular refused to cooperate with the committee’s questions. These 10, later known as the Hollywood Ten, lost their jobs and received sentences ranging from 1 to 12 months in prison. The studios, already slipping in influence and profit, cooperated to save themselves, and many producers signed an agreement stating that no communists would be allowed to work in Hollywood.

The hearings, which recommenced in 1951 with the rise of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s influence, turned into a kind of witch hunt as committee members asked witnesses to testify against their associates, and a blacklist of suspected communists evolved. More than 324 individuals lost their jobs in the film industry as a result of blacklisting (the denial of work in a specific field or industry) and HUAC investigations (Georgakas, 2004; Mills, 2007; Dressler et al., 2005).

Down With the Establishment: Youth Culture of the 1960s and 1970s

Movies of the late 1960s began attracting a younger demographic, as a growing number of young people became drawn to films like Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969)—all revolutionary in their genres—that displayed a sentiment of unrest toward conventional social orders and included some of the earliest instances of realistic and brutal violence in film. These four films, in particular, grossed a substantial amount of money at the box office, prompting producers to churn out low-budget copycats to tap into a new, profitable market (Motion Pictures). While this led to a rise in youth-culture films, few of them saw great success. However, the new liberal attitudes toward depictions of sex and violence in these films represented a sea of change in the movie industry that manifested in many movies of the 1970s, including Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), and Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), all four of which saw great financial success (Britannica Online; Belton, 1994).

Blockbusters, Knockoffs, and Sequels

In the 1970s, with the rise of filmmakers such as Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Martin Scorsese, a new breed of directors emerged. These young, film-school-educated directors contributed a sense of professionalism, sophistication, and technical mastery to their work, leading to a wave of blockbuster productions, including Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Star Wars (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). The computer-generated special effects available at the time also contributed to the success of several large-budget productions. In response to these and several earlier blockbusters, movie production and marketing techniques also began to shift, with studios investing more money in fewer films in the hopes of producing more big successes. For the first time, the hefty sums producers and distributors invested didn’t go solely to production costs; distributors began to discover the benefits of TV and radio advertising and found that doubling their advertising costs could increase profits by as much as three or four times. With the opening of Jaws, one of the five top-grossing films of the decade (and the highest-grossing film of all time until the release of Star Wars in 1977), Hollywood embraced the wide-release method of movie distribution, abandoning the release methods of earlier decades, in which a film would debut in only a handful of select theaters in major cities before it became gradually available to mass audiences. Studios released Jaws in 600 theaters simultaneously, and the big-budget films that followed came out in anywhere from 800 to 2,000 theaters nationwide on their opening weekends (Belton; Hanson & Garcia-Myers, 2000).

The major Hollywood studios of the late 1970s and early 1980s, now run by international corporations, tended to favor the conservative gamble of the tried and true, and as a result, the period saw an unprecedented number of high-budget sequels—as in the Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and Godfather films—as well as imitations and adaptations of earlier successful material, such as the plethora of “slasher” films that followed the success of the 1979 thriller Halloween. Additionally, corporations sought revenue sources beyond the movie theater, looking to the video and cable releases of their films. Introduced in 1975, the VCR became nearly ubiquitous in American homes by 1998, with 88.9 million households owning the appliance (Rosen & Meier, 2000). Cable television experienced slower growth, but the advent of VCRs provided people with a new reason to subscribe, and cable subsequently expanded as well (Rogers). And the newly introduced concept of film-based merchandise (toys, games, books, etc.) allowed companies to increase profits even more.

The 1990s and Beyond

The 1990s witnessed the rise of two divergent strands of cinema: the technically spectacular blockbuster, featuring special, computer-generated effects, and the independent, low-budget film. Studios enhanced the capabilities of special effects when they began manipulating film digitally, as seen in blockbusters such as Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Jurassic Park (1993). Films with an epic scope—such as Independence Day (1996), Titanic (1997), and The Matrix (1999)—also employed a range of computer animation techniques and special effects to wow audiences and draw more viewers to the big screen. Toy Story (1995), the first fully computer-animated film, and those that followed, such as Antz (1998), A Bug’s Life (1998), and Toy Story 2 (1999), showcased the improved capabilities of computer-generated animation (Sedman, 2000). At the same time, independent directors and producers, such as the Coen brothers and Spike Jonze, experienced increased popularity, often for lower-budget films that audiences were more likely to watch at home on video (Britannica Online). A prime example of this occurred at the 1996 Academy Awards program, when independent films dominated the Best Picture category. Only one movie from a big film studio earned a nomination—Jerry Maguire—while independent films earned the rest. The growth of both independent movies and special-effects-laden blockbusters continues to the present day.

The past decade and a half has ushered in an era of unprecedented transformation for the film industry, largely driven by the ascendance of streaming services and fundamental shifts in how audiences consume media. Companies like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime Video, later joined by studio-backed giants such as Disney+, HBO Max, and Apple TV+, revolutionized distribution and consumption patterns. This digital revolution led to the precipitous decline of physical media sales and rentals (like DVDs and Blu-rays) as consumers embraced the convenience of on-demand digital access. Studios rapidly adapted, transitioning from traditional theatrical exclusivity to diverse release strategies, including shorter theatrical windows, Premium Video On Demand (PVOD) releases, and even direct-to-streaming premieres, fundamentally altering traditional revenue models.

Technologically, the industry has continued its relentless march into the digital realm. Digital filmmaking became the undisputed standard for production, with advancements in camera technology offering stunning resolution and dynamic range. Crucially, Visual Effects (VFX) and Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI) reached new levels of realism and sophistication, enabling the creation of entire virtual worlds and photorealistic characters, often utilizing technologies like virtual production with LED walls. This era also solidified the dominance of franchise filmmaking and established intellectual property (IP), with cinematic universes like the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars generating multi-billion-dollar revenues, shaping release schedules and studio strategies for years in advance. Simultaneously, the global marketplace, particularly the booming box office in regions like China, became increasingly vital for a film’s overall profitability, influencing production decisions and storytelling.

Alongside these industry shifts, critical cultural movements such as #MeToo and #OscarsSoWhite have spurred crucial conversations about diversity, representation, and accountability within Hollywood, leading to new industry standards, initiatives, and a greater emphasis on inclusive storytelling and equitable workplaces. The film industry, therefore, stands at a fascinating juncture, constantly innovating and adapting in response to technological evolution, changing consumer habits, global market dynamics, and ongoing societal dialogues.