8.3 Movies and Culture

Movies Mirror Culture

The relationship between movies and culture is a complex and dynamic one. In contrast, American movies certainly influence the mass culture that consumes them; they also represent an integral part of that culture, a product of it, and therefore a reflection of dominant concerns, attitudes, and beliefs. When considering the relationship between film and culture, it is essential to recognize that, while certain ideologies may prevail in a given era, American culture represents a diverse population that constantly evolves from one period to the next. Mainstream films produced in the late 1940s and into the 1950s, for example, reflected the conservatism that dominated the sociopolitical arenas of the time. However, by the 1960s, a reactionary youth culture began to emerge in opposition to the dominant institutions, and these anti-establishment views soon found their way onto the screen—a far cry from the attitudes most commonly represented only a few years earlier.

Some characterize movies as America’s storytellers. Not only do Hollywood films reflect certain commonly held attitudes and beliefs about what it means to be American, but they also portray contemporary trends, issues, and events, serving as records of the eras that produced them. Consider, for example, films about the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks: Fahrenheit 9/11, World Trade Center, United 93, and others. These films emerged from a seminal event of the time, one that preoccupied the American consciousness for years after it occurred.

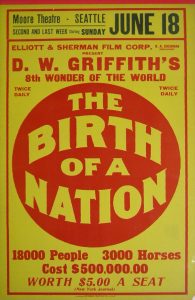

Birth of a Nation

In 1915, director D. W. Griffith established his reputation with the highly successful film The Birth of a Nation, based on Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman, a pro-segregation narrative about the American South during and after the Civil War. At the time, The Birth of a Nation stood as the longest feature film ever made, at almost 3 hours, and contained huge battle scenes that amazed and delighted audiences. Griffith’s storytelling ability helped solidify the narrative style that would go on to dominate the feature film genre. He also experimented with editing techniques, such as close-ups, jump cuts, and parallel editing, which contributed to the film’s artistic achievement. The Birth of a Nation would go on to earn more money than any other film in the silent film era (although Griffith would lose a substantial portion of it making his next film, the box office flop Intolerance).

Griffith’s film found success largely because it captured the social and cultural tensions of the era. As American studies specialist Lary May has argued, “[Griffith’s] films dramatized every major concern of the day (May, 1997).” In the early 20th century, fears about recent waves of immigrants had led to certain racist attitudes in mass culture, with “scientific” theories of the time purporting to link race with inborn traits like intelligence and other capabilities. Additionally, the dominant political climate, largely a reaction against populist labor movements, reflected the viewpoints of conservative elitism, eager to attribute social inequalities to natural human differences (Darity). According to a report by the New York Evening Post after the film’s release, even some Northern audiences “clapped when the masked riders took vengeance on Negroes (Higham).” However, the outrage many groups expressed about the film serves as a good reminder that American culture does not behave monolithically. Strong contingents in opposition to dominant ideologies can and do exist.

While critics praised the film for its narrative complexity and epic scope, the film outraged others. It even started riots at several screenings because of its highly controversial, openly racist attitudes, which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and blamed formerly enslaved people for the destruction of the war (Higham). Many Americans joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in denouncing the film, and the National Board of Review eventually cut a number of the film’s racist sections (May). This reflects the cultural attitudes of the early 1900s, a time when the divided nation enforced Jim Crow laws and segregation. In 1992, the Library of Congress classified the film among the “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant films” in U.S. history.

“The American Way”

Until the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, American films after World War I generally reflected the neutral, isolationist stance that prevailed in politics and culture. However, after the United States entered the war in Europe, the government enlisted Hollywood to help with the war effort, opening the federal Bureau of Motion Picture Affairs in Los Angeles. Bureau officials served in an advisory capacity on the production of war-related films, an effort with which the studios cooperated. As a result, films tended to feature patriotic themes designed to produce feelings of pride and confidence in America and to designate it and its allies as forces of good. For instance, the critically acclaimed Casablanca portrays the detrimental effects of fascism, illustrates the values that heroes like Victor Laszlo hold, and depicts America as a haven where refugees can find democracy and freedom (Digital History).

These early World War II films sometimes became overtly propagandist, intended to influence American attitudes rather than present a genuine reflection of American sentiments toward the war. The U.S. Army developed Frank Capra’s Why We Fight films, for example, first produced in 1942 and later shown to general audiences; they delivered a war message through narrative (Koppes & Black, 1987). As the war continued, however, filmmakers opted to forego patriotic themes for a more serious reflection of American sentiments, as exemplified by films like Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat.

In Mike Nichols’s 1967 film The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman, as the film’s protagonist, enters into a romantic affair with the wife of his father’s business partner. However, Mrs. Robinson and the other adults in the movie fail to understand the young, alienated hero, who eventually rebels against them. The Graduate, which brought in more than $44 million at the box office, reflected the attitudes of many members of a young generation growing increasingly dissatisfied with what they perceived as repressive social codes established by their more conservative elders (Dirks).

This baby boomer generation came of age during the Korean and Vietnam wars. Not only did the youth culture express cynicism toward the patriotic, pro-war stance of their World War II–era elders, but they also displayed a fierce resistance toward institutional authority in general, epitomized in the 1967 hit film Bonnie and Clyde. In the movie, a young outlaw couple sets out on a cross-country bank-robbing spree until they’re killed in a violent police ambush at the film’s close (Belton).

Bonnie and Clyde’s violence provides one example of the ways films at the time tested the limits of permissible on-screen material. The youth culture’s liberal attitudes toward formerly taboo subjects like sexuality and drugs began to emerge in film during the late 1960s. Like Bonnie and Clyde, Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 Western The Wild Bunch displays an early example of aestheticized violence in cinema. The wildly popular Easy Rider (1969)—containing drugs, sex, and violence—may owe a good deal of its initial success to liberalized audiences. And in the same year, Midnight Cowboy, one of the first Hollywood films to receive an X rating (in this case for its sexual content), won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture (Belton). As the release and subsequent successful reception of these films attest, what at the decade’s outset had started as countercultural had, by the decade’s close, become mainstream.

The Hollywood Production Code

When the MPA (originally the MPPDA) first formed in 1922 to combat government censorship and promote artistic freedom, the association attempted to establish a system of self-regulation. However, by 1930—in part because of the transition to talking pictures—renewed criticism and calls for censorship from conservative groups made it clear to the MPPDA that the loose system of self-regulation did not offer enough protection. As a result, the MPPDA instituted the Production Code, also known as the Hays Code (after MPPDA director William H. Hays), which remained in effect until 1967. The code, which, according to motion picture producers, concerned itself with ensuring that movies remained “directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress, for higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking (History Matters), became strictly enforced starting in 1934, putting an end to most public complaints. However, many people in Hollywood resented its restrictiveness. Following a series of Supreme Court cases in the 1950s regarding the code’s restrictions on freedom of speech, the Production Code gradually weakened until it was replaced in 1967 with the MPAA rating system (American Decades Primary Sources, 2004).

The Payne Fund Studies

The Payne Fund Studies, a groundbreaking series of investigations conducted between 1928 and 1933, marked one of the first large-scale efforts to systematically analyze the effects of motion pictures on audiences, particularly children and adolescents. Undertaken by prominent psychologists, sociologists, and educators from various universities, these studies aimed to provide a scientific understanding of cinema’s impact during a period of rapidly expanding film popularity. Their extensive research culminated in the publication of a 12-volume report, which meticulously detailed their findings across diverse aspects of media influence, from sleep patterns to attitudes.

Among their key discoveries, the Payne Fund Studies identified that a relatively small number of fundamental themes appeared with high frequency across the vast majority of films produced during that era. These recurring thematic elements formed the backbone of cinematic storytelling and often dictated the genre and appeal of a given movie. The prominent themes identified included Crime, exploring illicit activities and their consequences; Sex, often depicted subtly given the era’s Hays Code, but frequently implied through romantic entanglements and suggestive situations; Love, a universal and central theme; Mystery, driving narratives through puzzles and investigations; and War, reflecting global conflicts and their human toll.

Further analysis revealed additional pervasive themes such as the portrayal of Children, either as central characters or elements influencing plot; History, bringing past events to life; Travel, showcasing exotic locales and adventures; Comedy, providing humor and levity; and Social Propaganda, subtly or overtly promoting certain societal values, behaviors, or political viewpoints. The findings of the Payne Fund Studies provided early insights into content analysis and laid foundational groundwork for subsequent media effects research, despite later critiques regarding their methodology and interpretation.

MPAA Ratings

As films like Bonnie and Clyde and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) tested the limits on violence and language, and it became clear that the Production Code needed to be replaced. In 1968, the MPAA established a rating system to categorize films based on potentially objectionable content. By providing officially designated categories for films that would not have passed Production Code standards of the past, the MPA opened a way for films to deal openly with mature content. The ratings system originally included four categories: G (suitable for general audiences), M (equivalent to the PG rating of today), R (restricted to adults over 16), and X (equivalent to today’s NC-17 rating).

The MPA rating system, with some modifications, remains in use today. Before releasing their films in theaters, studios submit them to the MPA board for a screening, during which advisers determine the most appropriate rating based on the film’s content. However, the MPA does not require studios to screen releases ahead of time—some studios release films without obtaining an MPAA rating at all. Commercially, less restrictive ratings generally provide more benefits, particularly in the case of adult-themed films that have the potential to earn the most restrictive rating, the NC-17. Some movie theaters will not screen an NC-17-rated movie. When filmmakers receive a more stringent rating than desired, they may resubmit the film for review after editing out objectionable scenes (Dick, 2006).

The Syntax of the Screen: Crafting Stories Through Grammar and Genre

Film and television, as powerful mass media, have meticulously developed an intricate “media grammar” over their respective histories, a sophisticated language built upon a precise combination of technical and artistic elements. This grammar allows filmmakers and television producers to communicate complex narratives, evoke specific emotions, and shape audience perception without relying solely on dialogue. Key components of this visual and auditory syntax include editing, which dictates the pace, rhythm, and flow of a story; camera angles, manipulating perspective and conveying power dynamics or intimacy; lighting, used to establish mood, highlight subjects, and create visual drama; movement, encompassing both camera motion and character blocking to guide the viewer’s eye and emphasize action; and sound, which includes dialogue, music, and effects, all contributing to atmosphere, tension, and narrative progression.

This rich media grammar is fundamental to the creation of popular film genres, which serve as recognizable frameworks for both creators and audiences. These genres often combine specific narrative conventions, visual styles, and thematic concerns. Common examples that audiences flock to include high-stakes action/adventure films, humorous comedies, emotionally driven romances, imaginative science fiction tales, thrilling suspense narratives, meticulously crafted historical dramas, chilling horror stories, classic Westerns, fantastical fantasy epics, vibrant musicals, compelling biographies, and profound dramas. Each genre leverages the established media grammar in unique ways to deliver a distinct viewing experience, demonstrating the versatility and depth of cinematic storytelling.

The New War Film: Cynicism and Anxiety

Unlike the patriotic war films of the World War II era, many of the movies about U.S. involvement in Vietnam reflected strong antiwar sentiment, criticizing American political policy and portraying war’s damaging effects on those who survived it. Films like Dr. Strangelove (1964), M*A*S*H (1970), The Deer Hunter (1978), and Apocalypse Now (1979) portray the military establishment in a negative light and blur clear-cut distinctions, such as the “us versus them” mentality that was present in earlier war films. These, and the dozens of Vietnam War films produced in the 1970s and 1980s—Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), for example—reflect the sense of defeat and lack of closure Americans felt after the Vietnam War and the emotional and psychological scars it left on the nation’s psyche (Dirks, 2010; Anderegg, 1991). A spate of military and politically themed films emerged during the 1980s as America recovered from defeat in Vietnam, while at the same time facing anxieties about the ongoing Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Fears about the possibility of nuclear war felt very real during the 1980s. Some film critics argue that these anxieties manifested not only in overtly political films of the time but also in the popularity of horror films, like Halloween and Friday the 13th, which feature a mysterious and unkillable monster, and in the popularity of the fantastic in films like E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Star Wars, which offer imaginative escapes (Wood, 1986).

Movies Shape Culture

Just as movies reflect the anxieties, beliefs, and values of the cultures that produce them, they also help to shape and solidify a culture’s beliefs. Sometimes the influence is trivial, as in the case of fashion trends or idiomatic expressions. After the release of Flashdance in 1983, for instance, torn T-shirts and leg warmers became hallmarks of 1980s fashion (Pemberton-Sikes, 2006). However, sometimes the impact can lead to profound social or political reform or reshape ideologies.

Film and the Rise of Mass Culture

Between the 1890s and approximately 1920, American culture underwent a period of rapid industrialization. As people moved from farms to urban centers of industrial production, urban areas began to hold increasingly larger concentrations of the population. At the same time, film and other methods of mass communication (advertising and radio) developed, whose messages concerning tastes, desires, customs, speech, and behavior spread from these population centers to outlying areas across the country. Early mass-communication media sought to erode regional differences and foster a more homogenized, standardized culture.

Film played a key role in this development, as viewers began to imitate the speech, dress, and behavior of their everyday heroes on the silver screen (Mintz, 2007). In 1911, the Vitagraph company began publishing The Motion Picture Magazine, America’s first fan magazine. Originally conceived as a marketing tool to keep audiences interested in Vitagraph’s pictures and major actors, The Motion Picture Magazine played a crucial role in shaping the concept of the film star in the American imagination. Fans became obsessed with the off-screen lives of their favorite celebrities, like Pearl White, Florence Lawrence, and Mary Pickford (Doyle, 2008).

American Myths and Traditions

What does it mean to live like an American? This country’s citizens formulate their identity based on the commonly held beliefs or myths about shared experiences, and the media often disseminates and reinforces these American myths. One example of a popular American myth, dating back to the writings of Thomas Jefferson and other founders, emphasizes the value of individualism—a celebration of the ordinary person as a hero or reformer. With the rise of mass culture, the myth of the individual became increasingly appealing because it provided people with a sense of autonomy and individuality in the face of an increasingly homogenized culture. The hero myth finds embodiment in the Western, a popular film genre from the silent era through the 1960s, in which the lone cowboy, a seminomadic wanderer, navigates a lawless and often dangerous frontier, as seen in 1952’s High Noon. From 1926 until 1967, Westerns accounted for nearly a quarter of all films produced. In other films, like Frank Capra’s 1946 movie It’s a Wonderful Life, the individual triumphs by standing up to injustice, reinforcing the belief that one person can make a difference in the world (Belton). And in more recent films, hero figures such as Tony Stark (Marvel Cinematic Universe), Furiosa (Mad Max: Fury Road), Dr. Robert Neville (I am Legend), and John Wick (John Wick) have continued to emphasize individualism.

Social Issues in Film

As D.W. Griffith recognized nearly a century ago, film has enormous power as a medium to influence public opinion. Ever since Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation sparked strong public reactions in 1915, filmmakers have produced movies that address social issues, sometimes subtly, and sometimes very directly. Recent examples include Parasite (2019), which offers a scathing critique of class inequality, and The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020), which examines the political turmoil of the 1960s. Additionally, the rise of streaming platforms has made it easier for audiences to access documentaries like I Am Greta (2020), which highlights the climate crisis, and Collective (2019), which investigates a corruption scandal in Romania sparked by a nightclub fire. These films have the potential to shape cultural attitudes and drive social change.

In the 2010s and 2020s, documentaries continued to enjoy significant cultural and commercial success. Films like Fyre (2019), which expose a fraudulent music festival, and Free Solo (2018), which documents a daring rock climbing feat, have demonstrated the power of documentary filmmaking to capture audiences’ attention and spark conversations. Moreover, the growth of streaming platforms has allowed for the distribution of a wider range of documentaries, including those with niche or politically charged topics.

Michael Moore remains a prominent figure in documentary filmmaking, known for his politically charged films that often criticize corporate power and government policies. His 2007 film, Sicko, offered a scathing critique of the American healthcare system, sparking debates about universal healthcare in the United States. While some critics have accused Moore of producing propagandistic material under the guise of documentary because of his films’ strong biases, his films have proven popular with audiences, with four of his documentaries ranking among the highest-grossing documentaries of all time. Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), which criticized the second Bush administration and its involvement in the Iraq War, earned $119 million at the box office, making it the most successful documentary of all time (Dirks, 2006). Other filmmakers, such as Ava DuVernay and Raoul Peck, have also utilized documentaries to address significant social and political issues, demonstrating the enduring impact of this medium on shaping public opinion.

Unscripting Inequality: Gender, Power, and Progress in Film

The landscape of the film industry, particularly its cultural output, has been profoundly shaped by critical assessments of representation and seismic shifts in power dynamics. Among the most influential tools for evaluating gender representation in fiction is the Bechdel Test, a simple yet surprisingly potent metric proposed by cartoonist Alison Bechdel in her 1985 comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. To pass the test, a film must meet three criteria: it must feature at least two women, who talk to each other, about something other than a man. While often criticized for its simplicity and acknowledged by its creator as not being a measure of a film’s quality or feminist credentials, the Bechdel Test effectively highlights the pervasive lack of meaningful female interaction and narrative focus in countless mainstream movies, pointing to a systemic issue where women’s roles often revolve primarily around male characters. Popular films such as Fight Club, The Substance, Deadpool and Wolverine, The Big Lebowski, A Minecraft Movie, Star Wars, The Princess Bride, and many more have failed the test.

The underlying issues of gender disparity and power imbalances that the Bechdel Test subtly illuminates were brutally exposed by the #MeToo movement in Hollywood. Originating years earlier with activist Tarana Burke, the movement gained explosive global traction in late 2017 when numerous women came forward with accusations of sexual harassment and assault against powerful figures in the entertainment industry, most notably producer Harvey Weinstein. This collective uprising shattered a long-standing culture of silence and impunity, revealing how ingrained abuse of power, sexual misconduct, and gender discrimination were within Hollywood’s hierarchical structures. The movement prompted a reckoning, forcing studios, agencies, and production companies to confront widespread misconduct and leading to the downfall of many prominent figures.

The intersection of the Bechdel Test and the #MeToo movement underscores a critical truth about the film industry: issues of representation are inextricably linked to issues of power. A lack of diverse voices in storytelling (as highlighted by the Bechdel Test’s persistent failures) often correlates with environments where marginalized groups, particularly women, lack agency and are vulnerable to exploitation. The #MeToo movement propelled conversations about onscreen representation into broader discussions about off-screen safety, equitable hiring practices, and the dismantling of patriarchal systems that historically concentrated power in the hands of a few, often male, individuals. It became clear that simply putting more women on screen wasn’t enough; the industry also needed to ensure women were safe and empowered behind the camera, in executive suites, and at every level of production.

In the wake of #MeToo, Hollywood has seen tangible, albeit ongoing, shifts. Many studios and organizations implemented stricter codes of conduct, established clear reporting mechanisms for harassment, and invested in initiatives promoting diversity and inclusion both in front of and behind the camera. Organizations like Time’s Up emerged, dedicated to combating systemic injustice and inequality in the workplace. While the industry still has a long way to go to achieve true equity and eradicate all forms of misconduct, the Bechdel Test continues to serve as a simple, accessible reminder of the need for richer female narratives, while the #MeToo movement stands as a powerful testament to the collective courage required to challenge deeply entrenched abuses of power and foster a more equitable and respectful creative environment.