8.4 Issues and Trends in Film

Filmmaking serves both a commercial and artistic purpose. The current economic situation in the film industry, with increased production and marketing costs and lower audience turnouts in theaters, often sets the standard for the films that big studios choose to make. Ever wonder why studios release so many remakes and sequels? This section explains everything needed to understand the motivating factors behind those decisions.

The Influence of Hollywood

In the movie industry today, publicity and product serve the same purpose. Even films that get a lousy critical reception can do extremely well in ticket sales if their marketing campaigns manage to create enough hype. Similarly, two comparable films can produce very different results at the box office based on their levels of publicity. This explains why the film What Women Want, starring Mel Gibson, brought in $33.6 million in its opening weekend in 2000, while a few months later, The Million Dollar Hotel, also starring Gibson, only brought in $29,483 during its opening weekend (Nash Information Services, 2000; Nash Information Services, 2001). Unlike in the days of the Hollywood studio system, the performers alone cannot draw audiences to a film. The owners of the nation’s major movie theater chains have a keen awareness that a film’s success at the box office has everything to do with studio-generated marketing and publicity. One of the film industry’s leading studios, Paramount, produced What Women Want and then widely released it on 3,000 screens after an extensive marketing effort, while Lionsgate produced The Million Dollar Hotel. The independent studio did not possess the necessary marketing budget to fill enough seats for a wide release on opening weekend (Epstein, 2005).

The Hollywood “dream factory,” as Hortense Powdermaker labeled it in her 1950 book on the movie industry (Powdermaker), manufactures an experience that combines art with a commercial product (James, 1989) . While the studios of today do not practice vertical integration to the same extent as during the studio system era, the coordinated efforts of a film’s production team still resemble a machine calibrated for mass production. The films the studios churn out result from a capitalist enterprise that ultimately looks to the “bottom line” to guide most major decisions. Hollywood operates an industry, and as in any other industry in a mass market, its success relies on control of production resources and “raw materials” and on its access to mass distribution and marketing strategies to maximize the product’s reach and minimize competition (Belton). In this way, Hollywood has an enormous influence on the films to which the public has access.

Ever since the rise of the studio system in the 1930s, the majority of films have originated with the leading Hollywood studios. Today, the six big studios (Warner Bros. Pictures, 20th Century Studios (now owned by Disney), Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures, Sony Pictures Entertainment, and Walt Disney Studios) control roughly 85-90 percent of the film business (Dick). In the early years, audiences had familiarity with the major studios, their collections of actors and directors, and the types of films that each studio would likely release. All of that changed with the decline of the studio system; screenwriters, directors, scripts, and cinematographers no longer worked exclusively with one studio, so these days, while moviegoers may know the name of a film’s director and major actors, the identity of the studio that distributes it proves more challenging. However, studios still wield influence. For instance, they control the previews of coming attractions that play before a movie begins (Busis, 2010). Online marketing, TV commercials, and advertising partnerships with other industries—the name of an upcoming film, for instance, appearing on commercial products like Coke cans—can help the big-budget studios that have the resources to commit millions to prerelease advertising. Even though studios no longer own the country’s movie theater chains, the films produced by the big six studios frequent multiplexes. Unlike films by independents, big studio movies enjoy much larger ticket revenue opportunities.

Creating a major studio film is an incredibly complex and costly endeavor, with an average budget for a wide-release Hollywood production often exceeding $100 million. The largest impacts on this cost are typically driven by the film’s genre, as highly stylized projects like science fiction or fantasy epics demand extensive and expensive visual effects (VFX), elaborate set construction, and specialized technical crews. While a precise percentage can vary wildly, production costs—encompassing everything from set building, filming on location, acquiring specialized equipment, and crucially, crew and talent salaries—usually constitute the largest single component of a film’s budget. In major Hollywood productions, nearly all workers, from directors and actors to grips and gaffers, belong to various industry unions, which standardize wages and working conditions. The production journey typically begins when a filmmaker pitches a script to a studio, which often demands revisions to ensure commercial viability before agreeing to bankroll the project and handle distribution. Once a shooting schedule is constructed and major stars are signed, filming commences, a process that can span several weeks to many months. After principal photography wraps, the film enters an extensive post-production phase, which also lasts months, involving meticulous editing, sound design, musical scoring, and visual effects integration. Studios may also schedule reshoots during this period to capture additional footage or refine scenes, adding further to the overall cost. Importantly, the distribution of the final film now primarily involves sending digital copies to theaters, eliminating the previous costs associated with physical film prints.

Despite these immense investments, profitability in the film industry is far from guaranteed; it’s often cited that only about 20-30% of all films actually turn a profit (though some argue the consolidation of the film industry has increased the chances of success) when accounting for all production, marketing, and distribution costs worldwide. A movie’s profitability is fundamentally dependent on its initial budget relative to its revenue from theatrical runs, digital sales, streaming licenses, and ancillary markets. Hollywood generally employs two prominent, yet contrasting, formulas for achieving financial success.

Option #1 – The Blockbuster

This formula focuses on the big-budget blockbuster model, aiming for massive global theatrical returns. These films are characterized by extensive marketing tie-ins, major stars, and often rely heavily on special effects and established intellectual property to sell vast numbers of tickets. Recent examples include Dune: Part Two, which, with an estimated budget around $190 million, achieved critical acclaim and over $700 million globally, demonstrating that a well-executed tentpole can still be immensely profitable. Similarly, Barbie, despite a reported production budget of $145 million, became a cultural phenomenon, grossing over $1.4 billion worldwide, proving the power of smart marketing and broad appeal.

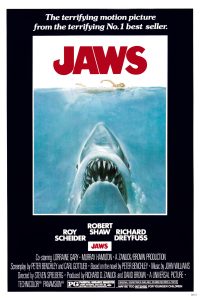

While it may seem like the major studios make hefty profits, moviemaking today poses a much riskier, less profitable enterprise than during the studio system era. The massive budgets required for the global marketing of a film require huge financial gambles. Most movies cost the studios much more to market and produce—upward of $100 million—than their box-office returns ever generate. With such high stakes, studios have come to rely on the handful of blockbuster films that keep them afloat, movies like Superman, Top Gun: Maverick, and Avengers: Endgame (New World Encyclopedia). The blockbuster film becomes a touchstone, not only for production values and storylines, but also for moviegoers’ expectations. Because studios know they can rely on certain predictable elements to draw audiences, they tend to invest the majority of their budgets in movies that fit the blockbuster mold. Remakes, movies with sequel setups, or films based on best-selling novels or comic books offer safer bets than original screenplays or movies with experimental or edgy themes.

James Cameron’s Titanic, the fourth-highest-grossing movie of all time, saw such success largely because it centered around a famous tragedy, contained predictable plot elements, and appealed to the widest possible range of audience demographics with romance, action, expensive special effects, and epic scope—meeting the blockbuster standard on several levels. The film’s astronomical $200 million production cost required the backing of two studios, Paramount and 20th Century Fox (Hansen & Garcia-Meyers). However, the rash of high-budget, and high-grossing, films that have appeared since—Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and its sequels, Avatar , The Last Jedi, The Lord of the Rings films, The Dark Knight, Frozen, and others—indicate that, for the time being, the blockbuster standard will continue to drive Hollywood production.

Option #2 – Independent Films

While the blockbuster still drives the industry, the formulaic nature of most Hollywood films of the 1980s, 1990s, and into the 2000s has opened a door for independent films to make their mark on the industry. Audiences have welcomed movies like Fight Club, Lost in Translation, and Juno as a change from standard Hollywood blockbusters, a trend that has continued with recent acclaimed films such as Get Out, Parasite, and Everything Everywhere All at Once. Few independent films reached the mainstream audience during the 1980s, but some developments in that decade paved the way for their increased popularity in the coming years. The Sundance Film Festival (originally the U.S. Film Festival) began in Park City, Utah, in 1980 as a way for independent filmmakers to showcase their work. Since then, the festival has grown to garner more public attention, and now often represents an opportunity for independents to find market backing from larger studios. In 1989, Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape, released by Miramax, became the first independent to break out of the art-house circuit and find its way into the multiplexes.

This formula emphasizes a smaller budget and a more focused strategy, hoping for a modest box office while aiming for a stellar return on investment (ROI). These films typically target a clear, often niche, audience, relying on compelling storytelling, strong word-of-mouth, or innovative concepts rather than spectacle. Success in this category often means the film’s total revenue significantly outstrips its relatively low production cost, leading to high profitability percentages. Modern examples include Anyone But You, a romantic comedy made for an estimated $25 million that grossed over $220 million worldwide, showcasing a strong ROI. Another example is the horror film Talk to Me, which was made for an estimated $4.5 million and went on to gross over $92 million globally, illustrating how a modest budget combined with effective genre execution can yield exceptional returns. These divergent approaches highlight the industry’s dual strategy for navigating financial success in an ever-evolving market. Pioneering this low-budget, high-profit model were films like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity, which famously turned minuscule production costs into hundreds of millions in global box office, demonstrating the immense potential for high returns on independent, innovative productions.

In the 1990s and 2000s, independent directors like the Coen brothers, Wes Anderson, Sofia Coppola, Quentin Tarantino, Chloe Zhao, Ari Aster, and Greta Gerwig made significant contributions to contemporary cinema, while studios like A24 revolutionized cinema. Tarantino’s 1994 film, Pulp Fiction, garnered attention for its experimental narrative structure, witty dialogue, and nonchalant approach to violence. It became the first independent film to break $100 million at the box office, proving that movies produced outside of the big six studios can elicit financial windfalls (Bergan, 2006).

The Role of Foreign Films

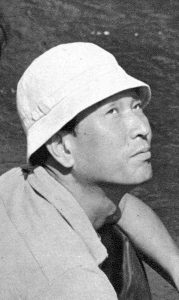

English-born Michael Apted, former president of the Director’s Guild of America, once said, “Europeans gave me the inspiration to make movies…but it was the Americans who showed me how to do it (Apted, 2007).” Major Hollywood studio films have dominated the movie industry worldwide since Hollywood’s golden age, yet American films have formed a symbiotic relationship of mutual influence with films from foreign markets. From the 1940s through the 1960s, for example, American filmmakers admired and emulated the work of overseas auteurs—directors like Ingmar Bergman (Sweden), Federico Fellini (Italy), François Truffaut (France), and Akira Kurosawa (Japan), whose personal, creative visions ended up reflected in the work of their American contemporaries (Pells, 2006). The concept of the auteur emerged in France in the late 1950s and early 1960s when French filmmaking underwent a rebirth in the form of the New Wave movement. The French New Wave, characterized by an independent production style that showcased the personal authorship of its young directors, continues to influence cinema to this day (Bergan). The generation of young, film school-educated directors that became prominent in American cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s owe a good deal of their stylistic techniques to the work of French New Wave directors François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, and Agnès Varda.

In today’s interconnected world, the impact of international cinema continues to be significant. The booming entertainment industry in Asia, for example, has fostered a cross-cultural exchange with Hollywood. Remakes of popular Japanese horror films like The Ring, Dark Water, and The Grudge have found success in the U.S., while Chinese martial arts epics like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Hero, and House of Flying Daggers have captivated global audiences. Meanwhile, U.S. studios have sought to tap into the thriving Asian market by acquiring the rights to films from South Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong, adapting them for Western audiences (Lee, 2005). For instance, recent successes include Parasite (South Korea), Squid Game (South Korea), and RRR (India), which have demonstrated the growing influence of international cinema and the diversity of storytelling that exists beyond Hollywood.

Cultural Imperialism or Globalization?

With the growth of Internet technology worldwide and the expansion of markets in rapidly developing countries, American films have increasingly found their way into movie theaters and home entertainment systems around the world. In the eyes of many people, the problem does not lie with the product the U.S. exports to outside markets, but the export of American culture that comes with that product. Just as films of the 1920s helped to shape a standardized, mass culture as moviegoers learned to imitate the dress and behavior of their favorite celebrities, contemporary film now helps to form a mass culture on a global scale, as the youth of foreign nations acquire the American speech, tastes, and attitudes reflected in film (Gienow-Hecht, 2006).

Staunch critics, feeling helpless to stop the erosion of their national cultures, accuse the United States of cultural imperialism through flashy Hollywood movies and commercialism. At the same time, others argue that the worldwide impact of Hollywood films reflects an inevitable part of globalization, a process that erodes national borders, opening the way for a free flow of ideas between cultures (Gienow-Hecht, 2006). For instance, provisions in NAFTA (and its successor, the USMCA) specifically exclude cultural industries, including entertainment, from its free trade provisions, protecting its domestic domestic cultural industries from the overwhelming influence of U.S. media.

Beyond the Camera: The Enduring Art of the Auteur

The concept of the auteur revolutionized film criticism, proposing that the director is the true author of a film, imbuing their works with a distinct personal vision, thematic preoccupations, and a recognizable stylistic signature across their entire filmography. This theory, emerging from French film critics in the 1950s, elevates the director beyond a mere craftsman to the central storyteller, whose consistent artistic voice can be identified regardless of the script or genre. Early proponents of this idea pointed to filmmakers whose unique perspectives permeated every aspect of their creations, leaving an indelible mark.

Among the most celebrated early auteurs are figures like Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless, Contempt, Band of Outsiders), a pivotal figure of the French New Wave whose experimental narratives redefined cinematic grammar. Similarly, Japan’s Akira Kurosawa (Seven Samurai, Rashomon, Ran) crafted epic human dramas with sweeping visual ambition, while Alfred Hitchcock (Psycho, Vertigo, Rear Window) became the undisputed “Master of Suspense,” renowned for his meticulous control over tension and psychological thrillers. Later generations saw Stanley Kubrick (2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining) push the boundaries of genre with his precise, often philosophical, and visually stunning films.

The auteur theory remains relevant for understanding a wide array of directorial voices who consistently imprint their artistic identities onto their work. Robert Altman (Nashville, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Gosford Park) was celebrated for his ensemble casts and naturalistic, overlapping dialogue. Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, The Departed) meticulously explores themes of guilt, redemption, and American masculinity, often set against urban backdrops. David Lynch (Mulholland Drive, Eraserhead, Blue Velvet) is known for his surreal, dreamlike, and often disturbing explorations of the subconscious. More contemporary figures like Spike Lee (Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, BlacKkKlansman) infuse their films with powerful social commentary and vibrant stylistic choices, while Wes Anderson (The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Royal Tenenbaums, Rushmore) is instantly recognizable for his symmetrical compositions, quirky characters, and distinctive visual aesthetic. The Coen Brothers (Fargo, No Country for Old Men, The Big Lebowski) have built a career on darkly comedic and often violent narratives that defy easy categorization. In recent years, directors like Denis Villeneuve (Arrival, Blade Runner 2049, Dune) have crafted visually ambitious, intellectually stimulating science fiction, and Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, Point Break) has redefined action and thriller genres with her intense, gritty realism and strong command of suspense. These filmmakers, regardless of genre or budget, exemplify the auteur’s enduring influence in shaping the art of cinema.

The Economics of Movies

With control of roughly 90 percent of U.S. film production, the big six Hollywood studios remain at the forefront of the American film industry, setting the standards for distribution, release, marketing, and production values. However, the high costs of moviemaking today mean that even successful studios must find moneymaking potential in crossover media—computer games, network TV and streaming rights, spin-off TV series, physical media (DVD, Blu-Ray, 4K, etc.), toys and other merchandise, books, and other after-market products—to help recoup their losses. The drive for aftermarket marketability in turn dictates the kinds of films studios decide to invest their money (Hansen & Garcia-Meyers).

Rising Costs and Big Budget Movies

In the days of the vertically integrated studio system, filmmaking underwent a streamlined process, neither as risky nor as expensive as the practice today. When producers, directors, screenwriters, art directors, actors, cinematographers, and other technical staff work under contract with one studio, the turnaround time for the casting and production of a film could last as little as three to four months. Beginning in the 1970s, after the decline of the studio system, the production costs for films increased dramatically, forcing the studios to invest more of their budgets in marketing efforts that could generate presales—that is, sales of distribution rights for a film in different sectors before the movie’s release (Hansen & Garcia-Meyers). This practice still happens today. Studios must negotiate contracts with actors, directors, and screenwriters, and with extended production times, costs have risen since the 1930s—when studios could make a film for around $300,000 (Schaefer, 1999).

Consider James Cameron’s Avatar, released in 2009, which cost close to $340 million, making it one of the most expensive films of all time. Where does such an astronomical budget go? When weighing the total costs of producing and releasing a film, about half of the money goes to advertising. In the case of Avatar, the film cost $190 million to make and around $150 million to market (Sherkat-Massoom, 2010; Keegan, 2009). Of that $190 million production budget, part goes toward above-the-line costs, the expenditures negotiated before filming begins, and part to below-the-line costs, those costs that generally remain fixed. Above-the-line costs include screenplay rights; salaries for the writer, producer, director, and leading actors; and salaries for directors’, actors’, and producers’ assistants. Below-the-line costs include the salaries for nonstarring cast members and technical crew, use of technical equipment, travel, locations, studio rental, and catering (Tirelli). For Avatar, the reported $190 million doesn’t include money for research and development of 3-D filming and computer-modeling technologies required to put the film together. Factoring in those costs, the total movie budget balloons closer to $500 million (Keegan). Fortunately for 20th Century Fox, Avatar made a profit over these expenses in box-office sales alone, raking in $750 million domestically (which made it the highest-grossing domestic movie of all time, a title now held by Star Wars: The Force Awakens, which is, coincidentally, the most expensive film ever made) in the first six months after its release (Box Office Mojo, 2010).

The Big Budget Flop

However, for every expensive film that has made out well at the box office, a handful of others have tanked (regardless of the film’s quality). Back in 1980, major Hollywood studio United Artists (UA) released its epic western Heaven’s Gate. The film cost nearly six times its original budget: $44 million instead of the proposed $7.6 million. The movie, which bombed at the box office, represented the largest failure in film history at the time, losing at least $40 million, and MGM bought out the studio as a result (Hall & Neale, 2010). Since then, Heaven’s Gate has become synonymous with commercial failure in the film industry (Dirks).

25 years later, the 2005 movie Sahara lost $78 million, making it one of the biggest financial flops in film history. The film’s initial production budget of $80 million eventually doubled to $160 million, due to complications with filming in Morocco and to numerous problems with the script (Bunting, 2007). Recent flops include The Lone Ranger, The Mummy, Dark Phoenix, Cats, Blade Runner 2049, and Morbius.

Piracy

Movie piracy used to come in two varieties: Either someone snuck into a theater with a video camera, turning out blurred, wobbly, off-colored copies of the original film, or somebody close to the film leaked a private copy intended for reviewers. In the digital age, however, crystal-clear bootlegs of movies on DVD/Blu-ray/4K Ultra HD Blu-ray and the Internet have become increasingly likely to appear illegally, posing a much greater threat to a film’s profitability. Tech-savvy pirates can even frequently sidestep safeguard techniques like digital watermarks (France, 2009).

In 2009, an unfinished copy of 20th Century Fox’s X-Men Origins: Wolverine appeared online one month before the movie’s release date in theaters. Within a week, more than 1 million people had downloaded the pirated film. Similar situations have occurred with other major movies, including X-Men Apocalypse, Avengers: Infinity War, and Justice League. The ease of theft made possible by the digitization of film and improved file-sharing technologies like BitTorrent software, a peer-to-peer protocol for transferring large quantities of information between users, have put increased financial strain on the movie industry. Emerging technologies such as streaming platforms and cloud storage services have expanded the accessibility and distribution of pirated content. Piracy not only affects the revenue of studios but also directly impacts filmmakers, who rely on box office success and licensing deals for their livelihoods. To combat piracy, studios have implemented digital rights management (DRM) technologies to protect their content. Additionally, legal action has been taken against piracy sites and individuals involved in distributing unauthorized content. However, the evolving landscape of piracy presents ongoing challenges for the industry, requiring continuous adaptation and innovation in anti-piracy measures.