9.2 The Evolution of Television

Since replacing radio as the most popular mass medium in the 1950s, television has played such an integral role in modern life that life without it would seem difficult to imagine for some. Both reflecting and shaping cultural values, television is sometimes criticized for its alleged negative influences on children and young people, and lauded for its ability to create a common experience for all its viewers. Major world events such as the John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King assassinations and the Vietnam War in the 1960s, the Challenger shuttle explosion in 1986, the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, and the impact and aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 have all played out on television, uniting millions of people in shared tragedy and hope. Today, as Internet technology and satellite broadcasting change how people watch television, the medium continues to evolve, solidifying its position as one of the most important inventions of the 20th century.

The Origins of Television

Inventors conceived the idea of television—which consists of an image being converted into electrical impulses, transmitted through wires or radio waves, and then reconverted into images—long before the technology to create it was developed. Early pioneers speculated that if they could separate audio waves from the electromagnetic spectrum to make radio, so too could they do the same to television waves to transmit visual images. As early as 1876, Boston civil servant George Carey envisioned complete television systems, putting forward drawings for a “selenium camera” that would enable people to “see by electricity” a year later (Federal Communications Commission, 2005).

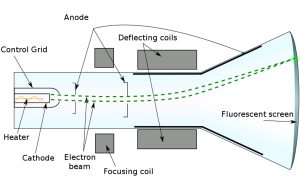

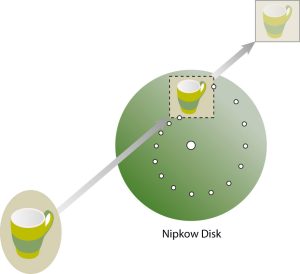

During the late 1800s, several technological advancements laid the groundwork for the development of television. The invention of the cathode ray tube (CRT) by German physicist Karl Ferdinand Braun in 1897 played a pivotal role as the precursor to the TV picture tube. Initially created as a scanning device known as the cathode ray oscilloscope, the CRT effectively combined the principles of the camera and electricity. It had a fluorescent screen that emitted visible light (in the form of images) when struck by a beam of electrons. During the 1880s, the mechanical scanner system created by German inventor Paul Nipkow consisted of a scanning disk, a large, flat metal disk with a series of small perforations arranged in a spiral pattern. As the disk rotated, light passed through the holes, separating pictures into pinpoints of light that could be transmitted as a series of electronic lines. The number of scanned lines equaled the number of perforations, and each rotation of the disk produced a television frame. Nipkow’s mechanical disk served as the foundation for experiments on the transmission of visual images for several decades.

In 1907, Russian scientist Boris Rosing used both the CRT and the mechanical scanner system in an experimental television system. With the CRT in the receiver, he used focused electron beams to display images, transmitting crude geometrical patterns onto the television screen. The mechanical disk system would operate as a camera, creating a primitive television system.

Mechanical Television versus Electronic Television

From the early experiments with visual transmissions, two types of television systems emerged: mechanical television and electronic television. Nipkow’s disk system formed the basis for mechanical television, pioneered by British inventor John Logie Baird in 1926 when he gave the world’s first public demonstration of a television system at Selfridge’s department store in London. He used mechanical rotating disks to scan moving images into electrical impulses, which he then transmitted by cable to a screen. Here, they showed up as a low-resolution pattern of light and dark. Baird’s first television program displayed the heads of two ventriloquist dummies, which he operated in front of the camera apparatus out of the audience’s sight. In 1928, Baird extended his system by transmitting a signal between London and New York. The following year, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) adopted his mechanical system, and by 1932, Baird had developed the first commercially viable television system, selling 10,000 sets. Despite its initial success, mechanical television had several technical limitations. Engineers could get no more than about 240 lines of resolution, meaning images would always appear slightly fuzzy (most modern televisions produce images of more than 600 lines of resolution). The use of a spinning disk also limited the number of new pictures viewers could see per second, resulting in excessive flickering. The mechanical aspect of television proved disadvantageous and required modifications for the technology to progress.

At the same time, Baird (and, separately, American inventor Charles Jenkins) developed the mechanical model, and other inventors worked on an electronic television system based on the CRT. While working on his father’s farm and observing the horizontal rows of crops he tended, Idaho teenager Philo Farnsworth realized that an electronic beam could scan a picture in horizontal lines in much the same way, which would reproduce the image almost instantaneously. In 1927, Farnsworth transmitted the first all-electronic TV picture by rotating a single straight line scratched onto a square piece of painted glass by 90 degrees.

Farnsworth barely profited from his invention; during World War II, the government suspended sales of TV sets, and by the time the war ended, Farnsworth’s original patents had almost expired. However, following the war, the RCA modified many of its key patents and applied the changes to improve television picture quality.

Having coexisted for several years, electronic television sets eventually began to replace mechanical systems. With better picture quality, reduced noise, a more compact size, and fewer visual limitations, the electronic system provided a significantly superior viewing experience compared to its predecessor. By 1939, broadcasts for mechanical television ended in the United States.

Early Broadcasting

Television broadcasting began as early as 1928, when the Federal Radio Commission authorized inventor Charles Jenkins to broadcast from W3XK, an experimental station in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, DC. The station broadcast silhouette images from motion picture films to the general public regularly, at a resolution of just 48 lines. Similar experimental stations ran broadcasts throughout the early 1930s. In 1939, RCA subsidiary NBC (National Broadcasting Company) became the first network to introduce regular television broadcasts, transmitting its inaugural telecast of the opening ceremonies at the New York World’s Fair. The station’s initial broadcasts were transmitted to just 400 television sets in the New York area, with an audience of 5,000 to 8,000 people.

Only a privileged few initially enjoyed television, with sets ranging from $200 to $600—a substantial sum in the 1930s, when the average annual income was $1,368 (KC Library). RCA offered four types of television receivers, which they sold in high-end department stores such as Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, and received channels 1 through 5. Early receivers featured a 5-, 9-, or 12-inch screen, a fraction of the size of modern TV sets. Television sales before World War II disappointed—an uncertain economic climate, the threat of war, the high cost of a television receiver, and the limited number of programs on offer deterred numerous prospective buyers. Many unsold television sets languished in storage and were sold after the war.

RCA radio’s rival, CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System), also began broadcasting regular programs in the 1930s. To prevent viewers from needing a separate television set for each network, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) established a single technical standard for all networks. In 1941, the panel recommended a 525-line system and an image rate of 30 frames per second. It also recommended that all U.S. television sets operate using analog signals (broadcast signals made of varying radio waves). The FCC replaced analog signals with digital ones (signals transmitted as binary code) in 2009.

With the outbreak of World War II, many companies, including RCA and General Electric, turned their attention to military production. Instead of commercial television sets, they began to churn out military electronic equipment. In addition, the war halted nearly all television broadcasting; many TV stations reduced their schedules to around four hours per week or went off the air altogether.

Color Technology

Although it did not become available until the 1950s and did not gain popularity until the 1960s, proposals for producing color television had been made as early as 1904. John Logie Baird demonstrated its use in 1928. As with his black-and-white television system, Baird adopted the mechanical method, using a Nipkow scanning disk with three spirals, one for each primary color (red, green, and blue). In 1940, CBS researchers, led by Hungarian television engineer Peter Goldmark, used Baird’s 1928 designs to develop a concept of mechanical color television that could reproduce the color seen by a camera lens.

Following World War II, the National Television System Committee (NTSC) developed an all-electronic color system that was compatible with black-and-white TV sets, gaining FCC approval in 1953. A year later, NBC made the first national color broadcast when it telecast the Tournament of Roses Parade, though few people owned color televisions and could enjoy this innovation. Despite the television industry’s support for the new technology, it would take another 10 years before color television gained widespread popularity in the United States. Black-and-white TV sets outnumbered color TV sets until 1972 (Klooster, 2009).

The Golden Age of Television

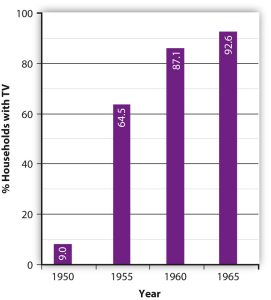

Historians have dubbed the 1950s the golden age of television, during which the medium experienced massive growth in popularity. Mass-production advances made during World War II substantially lowered the cost of purchasing a set, making television accessible to the masses. In 1945, the United States had fewer than 10,000 active TV sets. By 1950, this figure had risen to approximately 6 million, and by 1960, it had exceeded 60 million (World Book Encyclopedia, 2003). Many of the early television program formats borrowed heavily from network radio shows and failed to capitalize on the potential offered by the new medium. For example, newscasters read the news as they would have during a radio broadcast, and the network relied on newsreel companies to provide footage of news events. However, during the early 1950s, television programming began to branch out from radio broadcasting, borrowing from theater to create acclaimed dramatic anthologies such as Playhouse 90 and The U.S. Steel Hour, and producing high-quality news films to accompany coverage of daily events.

Two new types of programs—the magazine format and the TV spectacular—played an essential role in helping the networks gain control over the content of their broadcasts. A single sponsor developed and produced early television programs, which gave the sponsor significant control over the show’s content. By increasing program length from the standard 15-minute radio show to 30 minutes or longer, the networks substantially increased advertising costs for program sponsors, making it prohibitive for a single sponsor to support. Magazine programs such as The Today Show and The Tonight Show, which premiered in the early 1950s, featured multiple segments and ran for several hours. They also enjoyed daily, rather than weekly, broadcasts, drastically increasing advertising costs. As a result, the networks began to sell spot advertisements that ran for 30 or 60 seconds. Similarly, the television spectacular (now known as the television special) featured lengthy music-variety shows sponsored by multiple advertisers.

In the mid-1950s, the networks brought back the radio quiz show genre. Inexpensive and easy to produce, the trend caught on, and by the end of the 1957–1958 season, 22 quiz shows aired on network television, including CBS’s $64,000 Question. Shorter than some of the new types of programs, quiz shows enabled single corporate sponsors to have their names displayed on the set throughout the show. The popularity of the quiz show genre declined at the end of the decade, however, when audiences discovered that producers had rigged most of the shows by providing some contestants with the answers to the questions, allowing them to select the most likable or controversial candidates. When a slew of contestants accused the show Dotto of this in 1958, the networks rapidly dropped 20 quiz shows. A New York grand jury probe and a 1959 congressional investigation effectively ended prime-time quiz shows for 40 years, until ABC revived the genre with its launch of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire in 1999 (Boddy, 1990).

The Evolution of Television Programming

Radio had a significant influence on the early days of television programming. Many formats, genres, and even specific shows made a direct leap from the airwaves to the television screen. Variety shows, with their mix of musical acts, comedy sketches, and celebrity appearances, were immensely popular during television’s infancy, featuring stars like Ed Sullivan and Milton Berle who became household names. Similarly, anthology dramas, which presented a different story and cast each week, provided a bridge from radio’s dramatic serials.

A pivotal moment in this evolution came with the debut of I Love Lucy in 1951. This groundbreaking sitcom, starring Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, famously ended the era of exclusively live television by choosing to be taped, rather than filmed live. This innovative decision enabled the creation of high-quality copies of episodes, which could then be rebroadcast, giving rise to the concept of syndication. Ball and Arnaz shrewdly retained the syndication rights, ensuring the show’s enduring legacy and profitability. Its episodes continue to be broadcast and enjoyed by audiences today, a testament to its timeless appeal and the foresight of its creators.

Beyond I Love Lucy, other iconic programs emerged in television’s formative years. Children flocked to shows like Howdy Doody, while the Western genre, a carryover from radio, found immense success with series such as Gunsmoke. The 1950s and early 1960s also saw the rise of beloved comedies, such as The Honeymooners, and the thought-provoking science fiction anthology The Twilight Zone. These shows laid the groundwork for television’s cultural impact, culminating in watershed moments like The Ed Sullivan Show‘s broadcast on February 9, 1964, when an astonishing 73 million viewers tuned in to watch The Beatles perform, solidifying television’s power as a unifying cultural force.

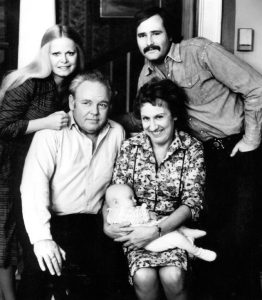

The evolution of television programming continued to accelerate in the following decades. The 1970s ushered in a new era for sports broadcasting with the debut of Monday Night Football in 1970, transforming sports into a cultural mainstay and a prime-time event. This growing prominence even led some sports, like the NBA, to adapt their rules to quicken the pace and enhance viewer engagement. The decade also saw the groundbreaking 1977 mini-series Roots, a 26-hour epic that captivated the nation and became the third-highest-rated program in history, demonstrating the power of long-form, serialized storytelling. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the 1970s also produced All in the Family, arguably the most critically acclaimed sitcom of the period.

The 1980s brought further innovation, notably with the debut of Hill Street Blues in 1980. This series pioneered a new genre of gritty, serialized police dramas, distinguishing itself with its large ensemble cast and multiple intertwining storylines —a format that would influence countless shows to follow. Its success underscored the creative vision of producers like Steven Bochco. Another transformative moment arrived in 1981 with the launch of MTV, famously kicked off by The Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star.” MTV demonstrated that fragmented content, delivered through music videos and niche programming, could generate significant profit and attract a dedicated audience, paving the way for specialized channels.

The competitive landscape of broadcast television also expanded significantly in the 1980s. In 1986, media mogul Rupert Murdoch launched the Fox Network, challenging the long-standing dominance of the “Big Three” (ABC, CBS, NBC). Fox strategically attracted independent stations by offering them free programming, thereby expanding its reach and establishing a foothold in the industry. Early successes, such as the edgy sitcom Married…with Children, helped define its brand. Over the years, Fox solidified its position as a top-rated broadcaster with a string of highly popular and influential shows, including NFL Football, The Simpsons, American Idol, Glee, and So You Think You Can Dance, proving its ability to deliver diverse hits across genres.

This continuous evolution laid the groundwork for what is often referred to as “America’s Second Golden Age of Television.” Beginning roughly in the late 1990s and flourishing into the 21st century, this era is defined by an explosion of high-quality, complex, and often serialized dramas and comedies. Fueled by the rise of cable networks and later streaming services, this period has witnessed a dramatic increase in creative freedom, enabling more nuanced storytelling, deeper character development, and a willingness to tackle challenging themes. Programs such as The Sopranos, which redefined the anti-hero and cinematic storytelling on cable; The Wire, celebrated for its intricate social commentary and realistic portrayal of urban institutions; Mad Men, lauded for its sophisticated writing, historical detail, and visual artistry; Breaking Bad, a masterclass in character transformation and escalating tension; and Game of Thrones, a massive cultural phenomenon that demonstrated epic scale and cinematic ambition on the small screen, have pushed artistic boundaries, attracted top-tier talent, and elevated television to an art form on par with, and often surpassing, feature films, fundamentally reshaping audience expectations for narrative depth and production quality.

The Evolution of Television News: From Early Broadcasts to the Digital Age

The roots of television news are deeply intertwined with radio, with many early programs and personalities transitioning directly to the visual medium. A towering figure in this early era was Edward R. Murrow, who gained widespread renown as a voice of World War II through his powerful radio broadcasts. He seamlessly moved to television with See It Now, a groundbreaking documentary series that harnessed the visual power of the new medium to explore critical social and political issues. A particularly impactful moment was Murrow’s courageous 1954 broadcast challenging Senator Joseph McCarthy, a pivotal event that showcased television’s potential for investigative journalism and later inspired the film and stage play Good Night, and Good Luck. Concurrently, Meet the Press debuted in 1947, establishing itself as television’s longest-running news and commentary program, while CBS-TV News began airing a concise 15-minute program on weeknights in 1948, a standard length for news broadcasts until the early 1960s.

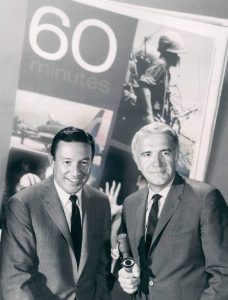

Television’s influence on public discourse dramatically expanded with the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates. These televised confrontations allowed millions of Americans to see the candidates side-by-side, with visual impressions playing a significant role in shaping voter perceptions. Recognizing this growing power, news programming began to expand. By 1963, major news shows had lengthened to one hour, often anchored by iconic figures like Walter Cronkite, widely regarded as “the most trusted man in America.” Another significant development in news programming during this time period was the debut of 60 Minutes on CBS in September 1968. This groundbreaking newsmagazine format, created by Don Hewitt, blended investigative reporting, newsmaker interviews, and in-depth profiles, becoming television’s longest-running prime-time series and setting a new standard for broadcast journalism. This period also saw the widespread adoption of crucial technologies such as videotape, satellite communication, and color broadcasting, which collectively revolutionized the immediacy, reach, and visual quality of news delivery, making it a truly national and often instantaneous experience.

A fundamental transformation in television news arrived with the launch of CNN (Cable News Network) in 1980. Founded by Ted Turner, this pioneering 24-hour news network was initially met with skepticism, sometimes derisively called “Chicken Noodle News.” However, Turner’s audacious vision, encapsulated by his promise that the station would not go off the air “until the world ends,” proved prescient. CNN’s defining moment came during the 1991 Gulf War, when its live, round-the-clock reporting from the conflict zone provided an unprecedented level of real-time information, solidifying its reputation as a global news leader and ushering in the era of continuous news cycles.

In the mid-1990s, the cable news landscape diversified further with the emergence of Fox News. Launched in 1996, Fox News quickly ascended to become one of the most financially successful news and cable networks (it has been the top-rated cable network since 2019) , cultivating a distinct conservative viewpoint that resonated with a large audience. Its success challenged the established news order and introduced a more overtly opinion-driven style of programming. However, the network faced significant reputational damage and legal scrutiny following its coverage of the 2020 U.S. presidential election, culminating in the high-profile Dominion Voting Systems v. Fox News defamation lawsuit, which raised serious questions about the accuracy and integrity of its reporting. Fox News settled the case for $787.5 million.

News programming has undergone profound and rapid changes recently, driven by the digital revolution. The proliferation of smartphones, social media, and streaming platforms has fragmented news consumption, forcing traditional outlets to adapt aggressively. News is now consumed across myriad digital channels, from dedicated news apps and streaming services to social media feeds, which have become primary news sources for many, particularly younger demographics. This shift has accelerated the pace of news, but also intensified challenges related to misinformation, filter bubbles, and the increasing polarization of news content. News organizations continue to grapple with these complexities, striving to maintain journalistic standards and financial viability in an ever-evolving media ecosystem.

The Rise of Cable Television

Formerly known as Community Antenna Television (CATV), cable television originated in the 1940s in remote or mountainous areas, including Arkansas, Oregon, and Pennsylvania, to enhance the poor reception of regular television signals. People in these communities would erect cable antennas on mountains or other high points, and homes connected to the towers would receive broadcast signals.

In the late 1950s, cable operators began experimenting with microwave technology to bring signals from distant cities. Taking advantage of their ability to receive long-distance broadcast signals, operators branched out from providing a local community service and began focusing on offering consumers more extensive programming choices. Rural parts of Pennsylvania, which had only three channels (one for each network), soon had more than double the original number of channels as operators began to import programs from independent stations in New York and Philadelphia. The service’s wider variety of channels and clearer reception soon attracted viewers from urban areas. By 1962, nearly 800 cable systems served about 850,000 subscribers.

Local TV stations viewed cable’s exponential growth as a threat, and broadcasters campaigned for the FCC to regulate it. The FCC responded by placing restrictions on the ability of cable systems to import signals from distant stations, which froze the development of cable television in major markets until the early 1970s. When gradual deregulation began to loosen the restrictions, cable operator Service Electric launched the service that would change the face of the cable television industry—pay TV. The 1972 Home Box Office (HBO) venture, in which customers paid a subscription fee to access premium cable television shows and video-on-demand products, became the nation’s first successful pay cable service. HBO’s use of a satellite to distribute its programming made the network available throughout the United States. This gave it an advantage over the microwave-distributed services, and other cable providers quickly followed suit. Further deregulation, provided by the 1984 Cable Act, enabled the industry to expand even further. By the end of the 1980s, nearly 53 million households had subscribed to cable television. In the 1990s, cable operators upgraded their systems by building higher-capacity hybrid networks of fiber-optic and coaxial cable. These broadband networks offer a multichannel television service, along with telephone, high-speed Internet, and advanced digital video services, all delivered over a single wire.

Ted Turner: A Cable Television Visionary

Ted Turner‘s remarkable journey as a media mogul began in 1963 when he inherited his father’s struggling billboard advertising company. Demonstrating an early knack for business, Turner not only revitalized the failing enterprise but also set his sights on the burgeoning television industry. In 1970, he acquired Channel 17, an independent UHF station in Atlanta. To ensure a steady stream of compelling programming for his new venture, Turner made the unconventional but brilliant move of purchasing professional sports teams: the Atlanta Braves baseball team in 1976 and the Atlanta Hawks basketball team in 1977. These live sports broadcasts became a crucial foundation for his ambitious plans.

The actual turning point came in 1976 when Turner transformed Channel 17 into SuperStation WTBS. By pioneering the use of satellite technology, he took a local station’s signal and distributed it nationally to cable systems across the United States. This innovative “superstation” concept revolutionized television distribution, offering cable subscribers an unprecedented variety of content, ranging from live sports to classic movies and syndicated reruns. Building on this success, Turner launched his most audacious project: the Cable News Network (CNN) on June 1, 1980.

Turner’s genius extended to his understanding of content maximization. He was a pioneer in “repackaging” content across multiple channels to extract maximum value. His acquisition of the vast MGM film library in 1986 led to the creation of Turner Network Television (TNT), which showcased classic films (TNT’s programming priorities would eventually shift and classic films found a home at Turner Classic Movies [TCM]). Similarly, the purchase of Hanna-Barbera (the animation studio behind iconic characters like Scooby-Doo and The Flintstones) in 1991, combined with the MGM cartoon collection, enabled him to launch Cartoon Network in 1992, a dedicated 24-hour animation channel. This strategic approach of leveraging owned content across specialized networks proved incredibly profitable and became a blueprint for future media conglomerates.

By the mid-1990s, Turner Broadcasting had grown into a formidable and diverse media empire. However, the rapidly consolidating media landscape and the need for further capital for expansion led to a major development. In 1996, Turner Broadcasting was acquired by Time Warner, one of the largest media mergers of its time. This deal integrated Turner’s extensive portfolio of channels, sports teams, and content libraries into Time Warner’s vast holdings. While the merger meant Ted Turner relinquished primary control of his properties, it solidified his enduring legacy as a visionary who built a media powerhouse from humble beginnings and fundamentally transformed the cable television industry.

The Emergence of Digital Television

Following the FCC standards established during the early 1940s, television sets received programs via analog signals composed of radio waves. The analog signal reached TV sets through three different methods: over the airwaves, through a cable wire, or by satellite transmission. Although the system remained in place for more than 60 years, it had several disadvantages. Analog systems were prone to static and distortion, resulting in a far poorer picture quality than films shown in movie theaters. As television sets grew increasingly larger, the limited resolution made scan lines painfully obvious, thereby reducing the image’s clarity. Companies around the world, most notably in Japan, began to develop technology that provided newer, better-quality television formats, and the broadcasting industry began to lobby the FCC to create a committee to study the desirability and impact of switching to digital television. A more efficient and flexible form of broadcast technology, digital television uses signals that translate TV images and sounds into binary code, working in much the same way as a computer. This means they require much less frequency space and also provide a far higher quality picture. In 1987, the Advisory Committee on Advanced Television Services began meeting to test various TV systems, both analog and digital. The committee ultimately agreed to switch from analog to digital format in 2009, allowing a transition period during which broadcasters could send their signals on both analog and digital channels. Once the switch took place, many older analog TV sets became unusable without a cable or satellite service or a digital converter. To retain consumers’ access to free over-the-air television, the federal government offered $40 gift cards to people who needed to buy a digital converter, expecting to recoup its costs by auctioning off the old analog broadcast spectrum to wireless companies (Steinberg, 2007). These companies eagerly wanted to gain access to the analog spectrum for mobile broadband projects because this frequency band allows signals to travel greater distances and penetrate buildings more easily.

The Era of High-Definition Television

The quest for superior picture quality in television began decades ago, with Japanese companies pioneering high-definition technology in conjunction with digital signals to deliver crystal-clear, wide-screen images. High-definition television (HDTV), first commercially available in the U.S. in 1998, revolutionized viewing by offering significantly higher resolution than standard definition, utilizing roughly five times as many pixels per frame to create a much more detailed and immersive experience. While initial HDTV sets were prohibitively expensive, costing between $5,000 and $10,000, prices rapidly declined, making the technology accessible to mainstream consumers. By the early 2010s, HDTV had become the dominant standard in American households, marking one of the fastest adoptions of a new television technology.

Today, the television landscape has progressed far beyond HDTV. The prevailing standard is now 4K Ultra High Definition (UHD), which boasts four times the pixels of Full HD (1080p HDTV), resulting in an even sharper, more vibrant, and detailed picture (3840 x 2160 pixels compared to 1920 x 1080 pixels). As of 2025, a significant majority of American households own a 4K-capable TV, with adoption rates continuing to climb. Beyond resolution, modern televisions also incorporate advanced display technologies such as OLED, QLED, and Mini-LED, which offer superior contrast, color accuracy, and brightness. These advancements, coupled with the widespread availability of 4K content from streaming services and other sources, have fundamentally reshaped the home viewing experience, pushing the boundaries of realism and immersion. The impact of new technologies on television is discussed in much greater detail in Section 9.5 “Influence of New Technologies” of this chapter.