9.4 Issues and Trends Facing the Television Industry

During television’s infancy, producers modeled the new medium on radio. They adapted popular radio shows, such as the police drama Dragnet and the western cowboy series Gunsmoke, for television. Single advertisers sponsored new television programs, using the same formula as radio programming. The three major networks—NBC, ABC, and CBS—dominated the television landscape, accounting for more than 95 percent of all prime-time viewing until the late 1970s. Today, the television industry finds itself in a far more complex time. Multiple advertisers sponsor programming now controlled by major media conglomerates, and the three major networks no longer dominate the airwaves but instead share their viewers with numerous cable channels (not to mention online platforms). Several factors contribute to these trends within the industry, including technological advancements, government regulations, and the emergence of new networks.

The Influence of Corporate Sponsorship

A single sponsor often developed, produced, and supported early television programs, which sometimes reaped the benefits of having its name inserted into the program’s title, such as The Colgate Comedy Hour, Camel News Caravan, and Goodyear Playhouse. However, as production costs soared during the 1950s (a single one-hour TV show cost a sponsor about $35,000 in 1952 compared with $90,000 at the end of the decade), sponsors became increasingly unable to bear the financial burden of promoting a show single-handedly. This suited the broadcast networks, which disliked the influence sponsors exerted over program content. Television executives, notably NBC’s Sylvester L. “Pat” Weaver, advocated for the magazine concept, in which advertisers purchased one- or two-minute blocks rather than the entire program, just as magazines contained multiple advertisements from different sponsors. The presence of numerous sponsors meant that no one advertiser controlled the program as a whole.

Although advertising agencies once relinquished control of production to networks, they have retained some influence over the content of programs. One executive commented, “If my client sells peanut butter and the script calls for a guy to be poisoned eating a peanut butter sandwich, you can bet we’re going to switch that poison to a martini (Newcomb).” While streaming services and digital advertising have introduced new avenues for advertisers, traditional methods such as financial support and sponsorship withdrawals still play a significant role.

While advertising agencies once relinquished control of production to networks, they have retained some influence over the content of programs, particularly through product placement and brand safety concerns. A notable recent example of this influence occurred with the HBO Max series And Just Like That… (the Sex and the City revival) in early 2022. In the premiere episode, a major character, Mr. Big, suffers a fatal heart attack after an intense workout on a Peloton exercise bike. Although Peloton confirmed they approved the bike’s appearance and an instructor’s cameo, they stated they were unaware of the specific plotline involving Mr. Big‘s death. The immediate negative association led to a significant drop in Peloton’s stock price and a public relations crisis for the brand. Peloton quickly responded with an ad featuring Chris Noth (Mr. Big’s actor) and the Peloton instructor, attempting to counter the negative narrative. This incident vividly demonstrates that even in the age of streaming, brands remain highly sensitive to how their products are portrayed and can react swiftly when content unexpectedly impacts their image, showcasing that financial support and potential withdrawal of future partnerships still play a significant role in content considerations.

Furthermore, the increasing political polarization in the United States has led advertisers to be more selective in their choices. Companies are more likely to consider social and ethical factors when deciding which programs to sponsor. For instance, in late 2018 and early 2019 Fox News program Tucker Carlson Tonight lost advertisers following controversial comments made by its host regarding immigration. Several prominent advertisers, including Pacific Life, Indeed, Bowflex (Nautilus), and IHOP, announced that they were pulling their advertisements from his show. These companies explicitly cited Carlson‘s statements as being misaligned with their brand values, demonstrating that advertisers continue to exert influence by withdrawing financial support when a program’s content becomes politically contentious. This highlights that even for established cable news programs, advertiser decisions can be a direct response to political and social controversies. This shift reflects a growing emphasis on corporate social responsibility and the desire to avoid negative publicity.

In conclusion, while the advertising landscape has evolved, advertisers continue to play a role in shaping program content. Factors such as public opinion, social media, and corporate social responsibility now influence their decisions more than ever before.

Public Television and Corporate Sponsorship

Corporate sponsorship does not just affect network television. Even public television has become subject to the influence of advertising. Established in 1969, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) evolved from a report by the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, which examined the role of educational, non-commercial television in society. The report recommended that the government finance public television to provide a diversity of programming during the network era—a service created “not to sell products” but to “enhance citizenship and public service (McCauley, 2003).” The government intended for public television to provide universal access to television for viewers in rural areas or those who could not afford private television services. PBS focused on educational program content, targeting viewers who did not appeal to the commercial networks and advertisers, such as the over-50 age demographic and children under 12.

The Carnegie Commission’s vision of a federally funded public television system was significantly curtailed by industry lobbying. While the original proposal called for a manufacturer’s excise tax on TV sets to establish a trust fund, the National Association of Broadcasters successfully opposed this measure. As a result, public television has historically relied on a combination of viewer contributions and federal funding.

Federal funding for public television has faced significant challenges in recent decades. Despite a successful effort to block President George W. Bush’s 2007 proposal to cut federal funding drastically, PBS has increasingly turned to corporate sponsorship to maintain its operations. By 2006, corporate sponsors funded over 25% of public television programming. While this has allowed many programs to continue, it has also raised concerns about the potential for commercialization. When PBS began selling banner advertisements on its website in 2006, Gary Ruskin, executive director of the consumer group Commercial Alert, commented, “It’s just one more intrusion of the commercial ethos into an organization that was supposed to be firmly noncommercial. The line between them and the commercial networks is getting fuzzier and fuzzier (Gold, 2006).” Such forms of advertising may become more prevalent in the future as President Donald Trump convinced Congress to enact a $9 billion claw back of public broadcasting funds in 2025.

The competitive landscape for public television has also undergone significant evolution. The rise of cable channels like The Discovery Channel and premium networks like HBO and Showtime has offered audiences a wider range of niche programming. PBS has had to rely on its long-running programs, such as Nova and Nature, to attract viewers. The future of public television remains uncertain as it navigates increased competition, shifting audience expectations, and the challenges posed by declining federal funding.

The Structure of Broadcast Television: Networks and Affiliates

The landscape of broadcast television is primarily defined by the symbiotic relationship between national broadcast networks and their local affiliate stations. Broadcast networks, such as ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox, are responsible for producing or acquiring a wide array of programming, including national news, prime-time dramas, comedies, and major sporting events. They then provide this content to their local affiliate stations across the nation. These affiliates are independently owned or operated stations that hold a license from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to broadcast over the airwaves in a specific geographic market. Each affiliate maintains its own equipment and local staff, enabling them to serve their community directly.

When an affiliate chooses to carry programming from its network, it typically receives a portion of the advertising revenue generated from national commercial spots within that programming. In some arrangements, affiliates may also receive direct financial compensation from the network for carrying their content. This national programming forms a significant part of the affiliate’s schedule. Still, local stations also produce their unique content, including local news, public affairs programs, and coverage of community events. Furthermore, affiliates can acquire syndicated programming—shows sold directly to individual stations—to fill their schedules. For all local and syndicated programming, the affiliate retains 100% of the advertising revenue generated, providing a crucial independent revenue stream alongside their network affiliations. Still, the traditional relationship between networks and affiliates has become more fraught with risk with the growth of the Internet, social media, and streaming platforms.

The Rise and Fall of the Network

The network era occurred between 1950 and 1970, when, aside from a small portion of airtime controlled by public television, the three major networks (known as the Big Three) dominated the television industry. In 1986, Rupert Murdoch, the head of multinational company News Corp, launched the Fox network, challenging the dominance of the Big Three. In its infancy, Fox acted as at best a minor irritation to the other networks. With fewer than 100 affiliated stations (the different networks all had more than 200 affiliates each), reaching just 80 percent of the nation’s households (compared with the Big Three’s 97 percent coverage rate), and broadcasting just one show (The Late Show Starring Joan Rivers), Fox barely impacted the ratings war. During the early 1990s, these dynamics began to change. The tremendous success of The Simpsons transformed the network, attracting large audiences, and Fox established itself as an edgy, youth-oriented network with shows such as Beverly Hills, 90210, Melrose Place, and In Living Color. Luring affiliates away from other networks to increase its viewership, Fox also extended its programming schedule beyond the initial two-night-a-week broadcasts. By the time the fledgling network acquired the rights to National Football League (NFL) games with its $1.58 billion NFL deal in 1994, entitling it to four years of NFL games, Fox had established itself as a worthy rival to the other three broadcast networks. Its success turned the Big Three into the Big Four. In the 1994–1995 television season, 43 percent of U.S. households were watching the Big Four at any given moment during prime time (Poniewozik, 2009).

Fox’s success in the mid-1990s prompted the launch of several smaller networks. UPN (initially a joint venture between Chris-Craft Industries’ United Television and Paramount Television, a subsidiary of Viacom) debuted on January 16, 1995. The WB (a joint venture between Warner Bros. Entertainment, a division of Time Warner, and Tribune Broadcasting) debuted slightly earlier on January 11, 1995. Using strategies similar to Fox, the networks initially began broadcasting programs two nights a week, expanding to a six-day schedule by 2000. Targeting young and minority audiences with shows such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Moesha, Dawson’s Creek, and The Wayans Bros., the new networks hoped to draw stations away from their old network affiliations.

However, rather than replicating Fox’s success, UPN and WB struggled to make an impact. Unable to attract many affiliate stations, the two fledgling networks reached fewer households than their larger rivals, as some smaller cities were unable to obtain their programming. High start-up costs, relatively low audience ratings, and increasing production expenses spelled the end of the “netlets,” a term coined by Variety magazine for minor-league networks that lacked a whole week’s worth of programming. After losing $1 billion each, parent companies CBS (having split from Viacom) and Time Warner agreed to merge UPN and WB, resulting in the creation of the CW network in 2006. Targeting the desirable 18–34 age group, the network retained the most popular shows from before the merger—America’s Next Top Model and Veronica Mars from UPN, and Beauty and the Geek and Smallville from WB—as well as launching new shows such as Gossip Girl and The Vampire Diaries. Despite its cofounders’ claims that the CW would earn the distinction of the “fifth great broadcast network,” the collaboration got off to a shaky start. Frequently outperformed by Spanish-language television network Univision in 2008 and with declining ratings among its target audience, critics began to question the future of the CW network (Grego, 2010). However, the relative success of shows such as Gossip Girl and 90210 gave the network a foothold on its intended demographic, quashing rumors that co-owners CBS Corporation and Warner Bros. might disband the network. Warner Bros. Television Group President Bruce Rosenblum said, “I think the built-in assumption and the expectation is that the CW is here to stay (Collins, 2009).”

In 2019, CBS Corporation and Warner Bros. merged their shares in The CW, forming a joint venture. However, in 2022, Nexstar Media Group acquired a majority stake in the network. This acquisition led to several changes, including a shift in programming focus towards more conservative content. The network has also faced challenges with declining viewership and the departure of several popular shows. Today, their most popular programs include Trivial Pursuit, Penn and Teller: Fool Us, and Sullivan’s Crossing. Despite setbacks, The CW continues to operate, albeit with a different trajectory than it had in previous years.

Cable Challenges the Networks

The increasing dominance of cable television proved a far greater challenge to network television than the emergence of smaller competitors. Between 1994 and 2009, the percentage of U.S. households watching the Big Four networks during prime time plummeted from 43 percent to 27 percent (Poniewozik, 2009). Two key factors contributed to the rapid growth of cable television networks: industry deregulation and the use of satellites to distribute local TV stations nationwide.

FCC regulations restricted the growth of cable television during the 1970s, which protected broadcasters by establishing franchising standards and enforcing anti-siphoning rules that prevented cable from taking sports and movie programming away from the networks. However, during the late 1970s, a court ruled that the FCC had exceeded its authority and repealed anti-siphoning rules. This decision paved the way for the development of cable movie channels, contributing to the exponential growth of cable in the 1980s and 1990s. Further deregulation of cable in the 1984 Cable Communications Policy Act removed restrictions on cable rates, enabling operators to charge what they wanted for cable services as long as the service had effective competition (a standard that over 90 percent of all cable markets could meet). Other deregulatory policies implemented during the 1980s included the elimination of public-service requirements and the reduction of regulated advertising in children’s programming, thereby expanding the scope of cable channel stations. The government intended for deregulation to encourage competition within the industry, but instead, it enabled local cable companies to establish monopolies nationwide. In 1989, U.S. Senator Al Gore of Tennessee commented, “Precipitous rate hikes of 100 percent or more in one year have not been unusual since cable was given total freedom to charge whatever the market will bear…. Since cable was deregulated, we have also witnessed an extraordinary concentration of control and integration by cable operators and program services, manifesting itself in blatantly anticompetitive behavior toward those who would compete with existing cable operators for the right to distribute services (Zaretsky, 1995).” The FCC reintroduced regulations for basic cable rates in 1992, by which time more than 56 million households (over 60 percent of the households with televisions) subscribed to a cable service.

The growth of cable TV gained momentum with the development of a national satellite distribution system. Pioneered by Time Inc., which founded cable network company HBO, the corporation used satellite transmission in 1975 to beam the “Thrilla from Manila”—the historic heavyweight boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier—into people’s homes. Shortly afterward, entrepreneur Ted Turner, owner of independent Atlanta-based station WTBS, uplinked his station’s signal onto the same satellite as HBO, enabling cable operators to downlink the station on one of their channels. Initially provided free to subscribers to encourage interest, the station offered TV reruns, wrestling, and live sports from Atlanta. Having created the first “superstation,” Turner expanded his realm by founding 24-hour news network CNN in 1980. At the end of the year, cable television networks offered 28 national programming services, marking the beginning of the cable revolution. Over the next decade, the industry experienced a period of rapid growth and increased popularity, and by 1994, viewers could choose from 94 basic and 20 premium cable services.

The rise of cable television has significantly reshaped the broadcasting landscape. Cable channels, with their ability to offer specialized programming, have introduced more explicit content, including heightened levels of violence, sexuality, and mature themes. To compete, major broadcast networks have gradually relaxed their content restrictions, allowing for shows with more graphic elements. While this has attracted larger audiences for programs like Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead, it has also drawn criticism from conservative groups.

Despite these efforts, broadcast networks have faced declining viewership. The increasing availability of streaming services and on-demand content has diverted audiences away from traditional television. As a result, broadcast networks have had to adapt their strategies to remain competitive in the evolving media landscape.

Nielsen Ratings: Measuring the Evolving Television Audience

Nielsen Media Research stands as the foremost authority in television audience measurement, meticulously tracking which shows are watched in homes across the country. This crucial data serves as the foundation for how advertising rates are formulated for television stations. However, accurately rating audiences presents significant challenges, particularly when accounting for the diverse landscape of major and minor broadcast networks, as well as the vast array of major and minor cable networks.

A primary hurdle in traditional measurement has been the rise of Digital Video Recorders (DVRs). To address the complexity of time-shifted viewing, Nielsen has developed various metrics beyond “Live Only” viewing. These include “Live + SD” (same day), which incorporates viewing within the same broadcast day, “Live + 3” (within three days), and “Live + 7” (within seven days), providing a more comprehensive picture of viewership. In larger markets, “people meters” are employed to gather granular data on who is watching. Additionally, “sweeps periods” in November, February, May, and July are critical times when Nielsen intensively measures the audience size of individual stations, directly influencing their advertising revenue potential.

Nielsen data has consistently highlighted a continuing trend of declining linear television viewership, reflecting a profound shift in consumer habits. In 2025, streaming surpassed both broadcast and cable television viewership for the first time. While the average American still dedicates a substantial amount of time to television viewing, the way they consume content has undergone a dramatic diversification. Key metrics, such as “Rating point” – representing the percentage of the potential television audience watching a show – and “Share” – indicating the percentage of television sets in use that are tuned to a specific show – remain vital, but their context is rapidly changing.

In response to the seismic shift towards digital consumption, Nielsen has expanded its measurement capabilities to include streaming services, acknowledging their growing dominance. A significant development has been the willingness of major streaming platforms to release their viewership data to Nielsen, providing a more holistic view of the total television landscape. This collaborative effort now includes data from a wide array of services such as Netflix, YouTube (central platform), Disney+, Hulu (SVOD content), Prime Video, HBO Max, Paramount+, Peacock, The Roku Channel, Pluto TV, Tubi, and Apple TV+, offering advertisers and content creators unprecedented insights into how audiences are engaging with content across all platforms.

Game On, TV On: How Sports Shaped the Small Screen

Sports events consistently rank among the most popular draws on television, captivating massive audiences worldwide. Iconic spectacles like the Super Bowl and the FIFA World Cup consistently command unparalleled viewership, underscoring the enduring appeal of live athletic competition. Beyond these global titans, sports broadcasting has also been a crucible for technological innovation. A landmark moment occurred during the 1963 Army-Navy football game, which famously marked the debut of instant replay, forever changing how fans experienced key plays. This innovation was swiftly followed by the introduction of slow-motion replay, which further enhanced the viewing experience and deepened engagement with the action on screen.

Within the realm of sports broadcasting, Disney’s ESPN has solidified its position as the dominant sports channel. While specific profitability figures can fluctuate and are often reported within broader segment results, ESPN consistently remains a significant revenue generator and one of Disney’s most valuable assets. For instance, in Disney’s fiscal first quarter ending December 28, 2024, the Sports segment, primarily driven by ESPN, reported revenues of $4.85 billion and saw a significant turnaround in operating income, moving from a loss in the prior year to a gain of $247 million. This underscores the substantial financial impact that major sports networks continue to have within large media conglomerates.

The appeal of sports on television transcends mere entertainment; it fosters a communal viewing experience, drives technological advancements in broadcasting, and remains a cornerstone of advertising revenue for networks. The ability to witness live, unscripted drama unfold, coupled with sophisticated production techniques like instant and slow-motion replays, ensures that sports will continue to be a central pillar of the television landscape.

Narrowcasting

Because the proliferation of cable channels provided viewers with numerous choices, broadcasters began to shift away from mass-oriented programming in favor of more targeted shows. Whereas the broadcast networks sought to obtain the widest audience possible by avoiding programs that might only appeal to a small minority of viewers, cable channels sought out niche audiences within specific demographic groups—a process known as narrowcasting. In much the same way that specialist magazines target readers interested in a particular sport or hobby, cable channels focus on one topic or a group of related topics that appeal to specific viewers (often those who have been overlooked by broadcast television). People interested in current affairs can tune into CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, or any number of other news channels, while those interested in sports can switch to ESPN, Fox Sports, or NBC Sports. Other channels focus on music, shopping, comedy, science fiction, or programs aimed at specific cultural or gender groups. Narrowcasting has proved beneficial for advertisers and marketers, who no longer need to time their communications based on the groups of people most likely to watch television at certain times of the day. Instead, they focus their approach on subscription channels that directly appeal to their target consumers.

A Feast for All Eyes: Food Network’s Commitment to Culinary Representation

The Food Network has long been recognized for its notable commitment to on-screen diversity, particularly when compared to many other television channels. This is especially evident in its popular competition series, such as Chopped, which consistently features a wide array of contestants from diverse ethnic backgrounds, culinary traditions, and professional experiences. This inclusive casting not only reflects the rich tapestry of the culinary world but also provides viewers with a broad spectrum of cooking styles and cultural influences.

Beyond Chopped, numerous other programs on the network contribute to its diverse representation. Shows like Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives, hosted by Guy Fieri, celebrate the varied culinary landscape of America by showcasing a multitude of local eateries run by people from different walks of life and serving a vast range of cuisines. Similarly, the network has featured and continues to feature a diverse roster of celebrity chefs and hosts, including those who highlight specific ethnic cuisines or bring unique cultural perspectives to their cooking demonstrations and competitions. This broad representation, both in front of and behind the camera, reinforces Food Network’s reputation as a channel that embraces and celebrates the global nature of food and cooking.

Television and Violence: A History of Research and Debate

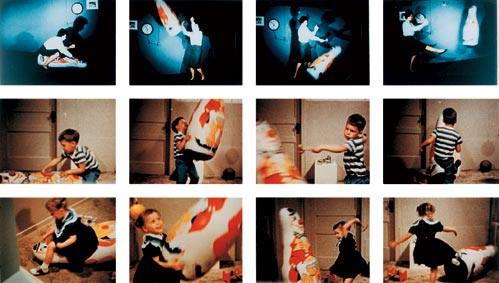

The relationship between television content and violent behavior has been a subject of extensive academic inquiry for decades, with hundreds of studies conducted and millions of dollars invested in understanding this complex dynamic. Early and influential research in the 1950-60s included the groundbreaking Bobo doll studies. These experiments demonstrated that children exposed to televised violence were significantly more likely to mimic the aggressive behaviors they witnessed in a laboratory setting, such as punching the Bobo doll, compared to those who were not exposed. These findings provided early evidence of observational learning about media.

Decades later, a comprehensive review of the accumulated research was presented in the influential 1992 report, “Big World, Small Screen: The Role of Television in American Society.” This report concluded that “The accumulated research demonstrates a correlation between viewing violence and aggressive behavior. Children and adults who watch a large number of aggressive programs also tend to hold attitudes and values that favor the use of violence.” It is crucial to note, however, that while this research established a strong correlation, correlation does not equate to causation. This distinction is vital in understanding that while a relationship exists, it does not necessarily mean that watching television violence directly causes aggressive behavior in all individuals, but rather suggests a complex interplay of factors where media consumption can play a role.