In this section, we will address the six principles of identity: how identities are plural, dynamic, have different and changing meanings, are contextual and intersectional, negotiated, and can be privileged, marginalized, silenced, or ignored

4.2.1: Identities are Plural

Every person has a range of identities, according to how they see themselves (and how others see them) in terms of gender, ethnicity, sexuality, age, and so on. This means that seeing an individual in terms of one aspect of their identity – as a black person, for example, rather than as (say) a black working-class woman who is also a social worker, a mother and a school governor – is inevitably reductive and misleading.

4.2.2: Identities are Dynamic

The identities people assume, and the relative importance they attach to them, change over time because of both personal change in their lives and change in the external world (for example, as a result of changing ideas about being differently abled). Consequently, identity should not be seen as something ‘fixed’ within people.

4.2.3: Identities Have Different and Changing Meanings

Aspects of identity may have different meanings at different times in people’s lives, and the meanings that they attribute to aspects of their identity (for example, ethnicity) may be different from the meaning it has for others. For example, being black may be a source of pride for you, but the basis of someone else’s negative stereotyping.

4.2.4: Identities are Contextual and Interactional

Different identities assume greater or less importance, and play different roles in different contexts and settings, and in interactions with different people. Different aspects of people’s identity may come to the fore in the workplace and in the home. For example, people might emphasize different aspects of themselves to different people (and different people may see different identities when they meet them).

4.2.5: Identities are Negotiated

In constructing their identities, people can only draw on terms that are available in society at that time, which have meanings and associations attached. However, people may attribute different meanings and importance to those labels. This means people always negotiate their identities in the context of the different meanings attached to them. Taking this contextual view of identity- as a social process that people engage in, rather than as a fixed essence inside them- is not to deny that particular identities are extremely important for certain groups and individuals. Being a Sikh, or a woman, or gay, may feel like the most important and ‘deepest’ part of you. However, a contextual and social model of identity is useful because it makes it difficult to reduce people to any one aspect of their identity, or to use one particular social identity (such as gender, race, sexual orientation, etc) as a way of explaining every aspect of their behavior and needs.

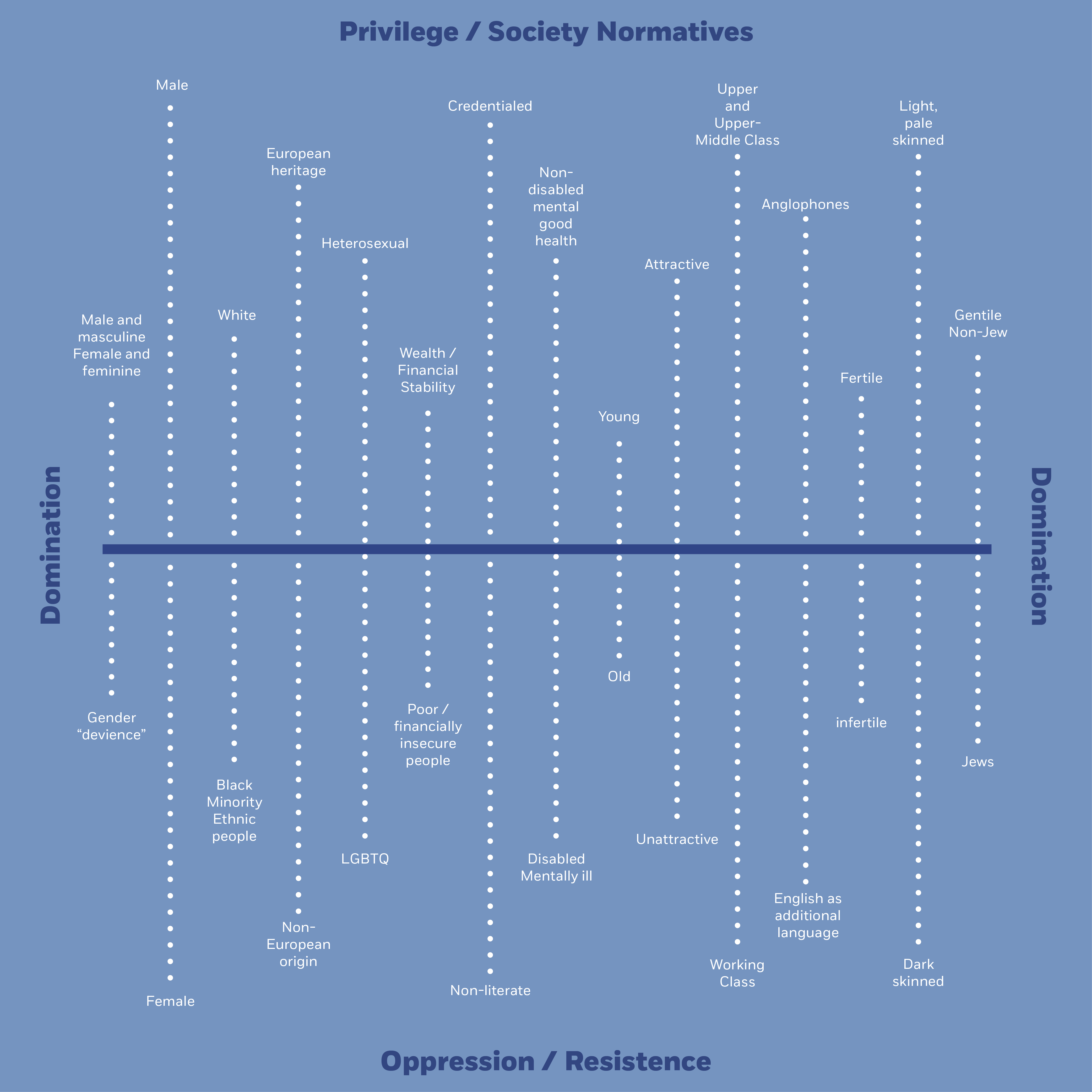

4.2.6: Identities can be Privileged, Marginalized, Silenced, or Ignored

The various cultural and co-cultural groups we belong to may work to advantage or disadvantage us, and, as such, our identities can be privileged or marginalized. For example, the co-cultural identity of race may grant some people with lighter skin colors advantages/privileges over those with darker skin color. Those who do have darker skin color have historically been rendered lesser than/inferior, or ‘othered’ in our culture. This is highlighted by the use of the common terminology white and non-white, which situates white as the norm and others and marginalizes. In addition, because humans are often grouped into binary categories, identities that are non-binary get silenced or ignored. For example, humans are usually placed into categories such as man or woman, straight or gay/lesbian. This ignores identities that fall outside of these categories or do not fit neatly into them, such as people who identify as pan or omni sexual. Conversely, those who identify as a cisgender man or woman have always had their identities embraced, acknowledged, and rendered the norm.

In addition, because our identities are plural and we are not just one thing or another, the intersectionality of our identities can work to both privilege and oppress us. For example, a white man who is of a lower economic status may experience privileges associated with skin color and maleness while simultaneously experiencing class oppression. It’s usually pretty easy to identify ways in which we feel we are oppressed or disadvantaged in some way, but a lot harder for most people to acknowledge ways in which they are privileged.

Intersectionality: Our identities are intersectional, which means that they are plural and we are not just one thing or another based off factors such as gender, race, class, etc; instead the components of our identities intersect with each other to create our unique positionalities. These various aspects of our identities and our positionality may simultaneously work to privilege or oppress us, based on the context.