In intimate relationships, such as friendships and romantic relationships, communication is key, as it is through communication that we begin, develop, maintain, and dissolve relationships. In this section, we will describe four stages of intimate relationships and present communication theories that help us better understand our communicative interactions during these stages.

8.2.1: Beginning Stage

In order to form a relationship with another person, we first must come into contact with them, whether it be face-to-face or through a mediated platform, such as a social networking site, dating site, or an app. In the beginning stage of the relationships, we interact with the other person to increase our knowledge about them and decide if we want to continue forming the relationship. During this stage, two communication theories can help us understand why we form relationships: Uncertainty Reduction Theory and Attraction Theory.

8.2.1.1: Uncertainty Reduction Theory:

Uncertainty Reduction Theory, also known as Initial Interaction Theory, can help us better understand the communicative behaviors involved in first interactions. The theory posits that, when interacting, people need information about the other party in order to reduce their uncertainty. Uncertainty is a sense of “not knowing” that people find to be unpleasant and seek to reduce through interpersonal communication. The theory identifies two types of uncertainty: cognitive and behavioral. Cognitive uncertainty pertains to the level of uncertainty associated with our thoughts (beliefs and attitudes) of each other in the situation.[4] Behavioral uncertainty is related to people’s actions and whether or not they fit our expectations for what we consider to be “normal” or not. Behavior that is outside of acceptable norms may increase uncertainty and reduce the chances for future interaction.

There are three types of strategies people may use to seek information about someone: passive (observing from afar), active (indirectly seeking information about the other), and interactive (seeking a direct exchange with the other). In gaining this information people are better able to predict the other’s behavior and resulting actions, all of which are crucial in the development of any relationship. The initial interaction of strangers can also be broken down into individual stages—the entry stage (when people engage in behavioral norms), the personal stage (when people tend to explore the other’s beliefs, attitudes, morals, etc.), and the exit stage

8.2.1.2: Attraction Theory:

Attraction Theory posits that three factors influence our attraction to others: their similarity to us, their proximity, and their interpersonal attractiveness (Alberts, Nakayama, & Martin, 2016).

- Similarity:

Have you ever heard the phrase ‘birds of a feather flock together’? Similarity is often an important determinant in whether or not we find someone else attractive. Research has shown that people are more strongly attracted to others who are similar in physical appearance, beliefs, attitudes, and who share similar co-cultural identities and backgrounds. Conversely, differences in these categories can lead to dislike or avoidance of others (Berkowitz, 1974; Singh & Ho, 2000; Bryne, London, & Reeves, 1968). - Proximity:

Proximity, how geographically and physically close we are to another person, also plays a role in relationship formation (Alberts, Nakayama, & Martin, 2016). In order to form a relationship with someone, we first have to come into contact with them. Historically, it was difficult to meet others outside of our geographical area. However, technology has transformed how we meet and carry out relationships since we are no longer constrained by geographic barriers. From social networking sites to mobile apps, we now have the ability to connect with anyone, anytime, anywhere. Mediated platforms have become a way to connect to others to start both romantic and platonic relationships because it is easier to connect with those who share similar interests and have similar relationship goals (such as hooking up, long-term relationship, non-monogamous relationship, etc). Still, when it comes to relationships, such as friendships, proximity is still one of the biggest determinants. Generally speaking, we are more likely to form relationships with people we actually meet face-to-face through, for example, being in the same class or working at the same place. - Interpersonal Attractiveness:

We communicate more with people we are attracted to (McCroskey & McCain, 1974, p. 261). Interpersonal attractiveness encompasses three components: physical attractiveness, social attractiveness, and task attractiveness (MrCroskey, McCrowskey, & Richmond, 2006). Physical attractiveness is the degree to which we find another person’s physical features to be pleasing. Social attractiveness encompasses characteristics such as friendliness, charisma, and warmth; whereas task attractiveness pertains to attraction based on another’s abilities, skills, and/or talents. (Alberts, Nakayama, & Martin, 2016, p. 192).

8.2.2: Developing Stage

The next stage of relationships is the development stage during which our communication and interactions with the other person increases. To help us better understand this stage, four communication theories explain the who, why, and how of relationship development, as well as some differences between face-to-face and mediated-communication relationship development. The theories are: Interpersonal Needs Theory, Social Exchange Theory, Social Penetration Theory, and Hyperpersonal Communication Theory.

8.2.2.1: Interpersonal Needs Theory:

(Image: © Cathy Thorne/www.everydaypeoplecartoons.com; printed with permission for use in I.C.A.T.)

(Image: © Cathy Thorne/www.everydaypeoplecartoons.com; printed with permission for use in I.C.A.T.)Interpersonal Needs Theory posits that we are likely to develop relationships with other people if they meet one or more of three basic interpersonal need. These three need operate on a continuum and are influenced by context (Schutz, W., 1966).

- Affection:

People have a need for affection and appreciation. This need can be fulfilled through family, friendships, and romantic relationships. and Some people may crave many intimate relationships while other may choose to limit them. - Control:

The need for control pertains to our ability to influence people, events, and their environments. Just like with affection, some people crave less control of people, events, and their environments while others crave more. For example, in a friendship, one person may want to be the one who always decides where to hang out and the other may be okay with that. However, the need for control can also vary by individual levels of motivation and context. For example, in a friendship we may place less importance on who calls the shots, while in the workplace we may seek greater influence on others and events. - Belonging:

Finally, people desire to be around other people. Similar to our other two needs, the need for belonging exists on a continuum, can vary between individuals and is based on context. Some people may limit their interactions or choose smaller groups while others may crave more frequent interactions and attention.

8.2.2.2: Social Penetration Theory:

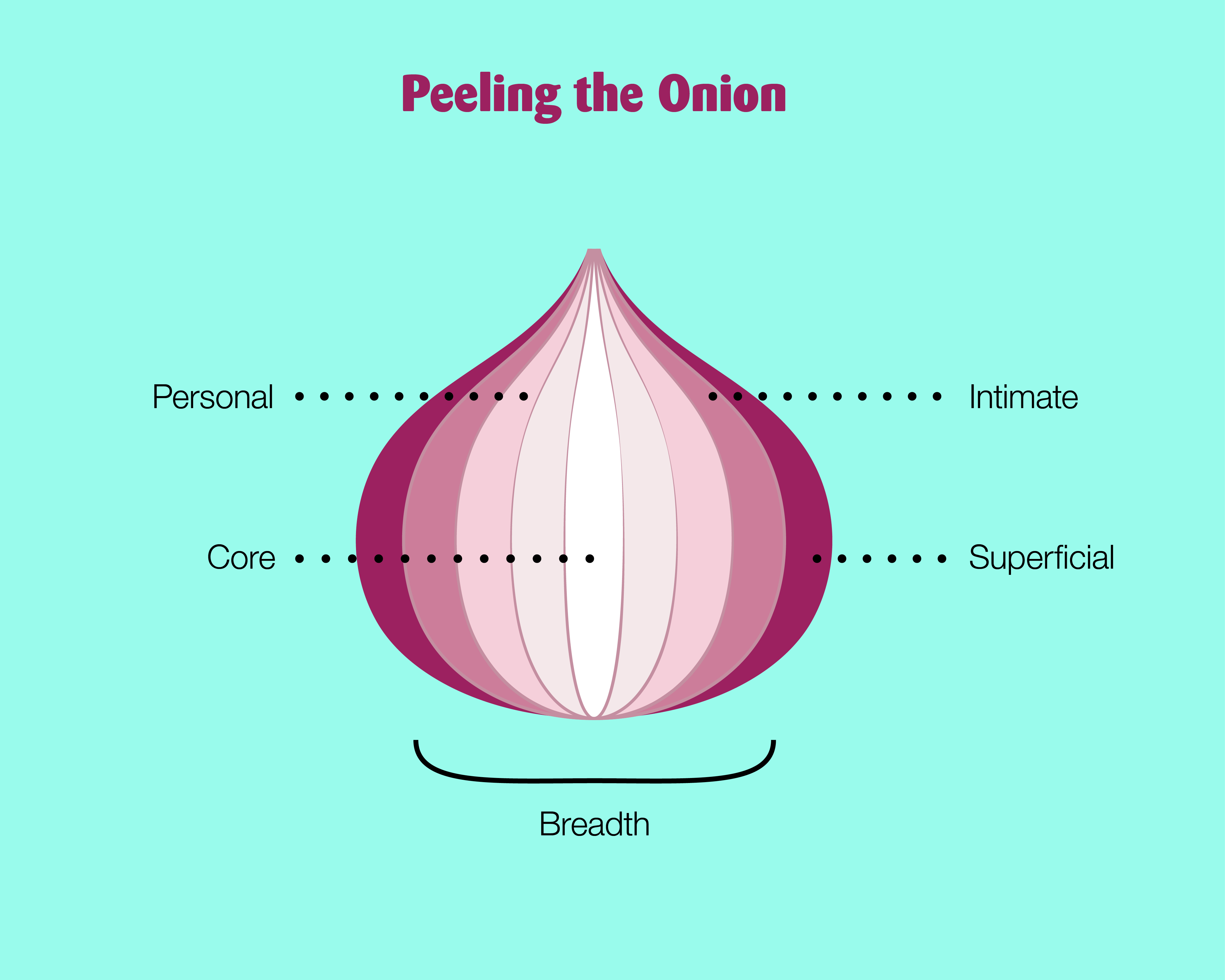

A key to understanding Social Penetration Theory is to first understand self-disclosure. Self-disclosure is the process of revealing information about yourself to others that is not readily known by them, and it plays a key role in the formation of relationships. As we get to know someone we engage in a reciprocal process of self-disclosure. The amount of self-disclosure changes in breadth and depth as the relationship develops. Depth pertains to how personal the information is where as breath refers to the range of topics that are discussed. Degrees of self-disclosure range from relatively safe (revealing your hobbies or musical preferences) to more personal topics (illuminating fears, dreams for the future, or fantasies). Typically, as relationships deepen and trust is established, self-disclosure increases in both breadth and depth. We tend to disclose facts about ourselves first (I am a Biology major), then move towards opinions (I feel the war is wrong), and finally disclose feelings (I’m sad that you said that).

An important aspect of self-disclosure is the rule of reciprocity. This rule states that self-disclosure between two people works best in a back and forth fashion. When you tell someone something personal, you probably expect them to do the same. When one person reveals more than another, there can be an imbalance in the relationship because the one who self discloses more may feel vulnerable as a result of sharing more personal information.

8.2.2.3: Social Exchange Theory:

Social Exchange Theory essentially entails a weighing of the costs and rewards in a given relationship (Harvey & Wenzel, 2006). Rewards are outcomes that we get from a relationship that benefit us in some way, such as companionship and/or social support. Costs can range from granting favors to providing emotional support. When we do not receive the outcomes or rewards that we think we deserve, then we may negatively evaluate the relationship, or at least a given exchange or moment in the relationship, and view ourselves as being under-benefited, which could lead to the eventual termination of the relationship. In an equitable relationship, costs and rewards are balanced, which usually leads to a positive evaluation of the relationship and satisfaction. Ultimately, relationships are more likely to succeed when there is satisfaction and commitment, meaning that we are pleased in a relationship intrinsically or by the rewards we receive.

8.2.2.4: Hyperpersonal Communication Theory:

Hyperpersonal Communication Theory examines how mediated-communication enables communicative advantages and how this can lead to intense, overly intimate, and idealized relationships. People who meet online have a better opportunity to make a favorable impression on the other. This is because we can decide which information we would like to share about ourselves by controlling our self-presentations online (O’Sullivan, 2002), giving us the power to disclose only our ‘good’ traits. According to Walther, we have the ability to present ourselves in highly strategic and highly positive ways. The asynchronous nature of mediated-communication also allows us to think about texts or emails before sending them. Further, prior to sending messages, we can rewrite them for clarity, sense, and relevancy. Online asynchronous experiences allow for “optimal and desirable” communication, ensuring that the messages are of high quality.

Additionally, because mediated communication enables us to selectively present ourselves, the exchange lacks ‘contrary cues,’. In face-to-face interactions, we would pay attention to not just what the person says, but also what they do. For example, the other person interacting rudely with a server over dinner would influence our overall impression of that person. However, we don’t necessarily get to see how a person acts with others and the world around them in mediated-communication relationships, which can lead to an idealized view of that other person that may not live up to reality.

8.2.3: Maintaining Stage

The next stage of relationships is the maintaining stage where the relationship is in a prolonged or continued state of relatively mutual satisfaction for both parties. During this stage, Relational Dialectics Theory can help us better understand how relationships are sustained.

8.2.3.1: Relational Dialectics:

Three relational dialectics influence our interpersonal relationships and understanding their role is key to maintaining healthy relationships.

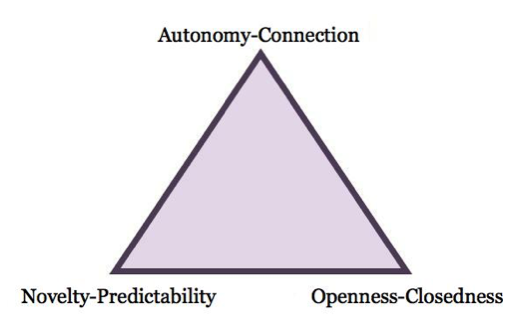

One way we can better understand our personal relationships is by understanding the notion of relational dialectics. Baxter (1988) describes three relational dialectics that are constantly at play in interpersonal relationships: autonomy-connection, novelty-predictability, and openness-closedness. Essentially, they are a continuum of needs for each participant in a relationship that must be negotiated by those involved.

- Autonomy-Connection:

refers to our need to have close connection with others as well as our need to have our own space and identity. We may miss our romantic partner when they are away but simultaneously enjoy and cherish that alone time. When you first enter a romantic relationship, you probably want to be around the other person as much as possible. As the relationship grows, you likely begin to desire fulfilling your need for autonomy, or alone time. In every relationship, each person must balance how much time to spend with the other, versus how much time to spend alone. - Novelty-Predictability:

is the idea that we desire predictability as well as spontaneity in our relationships. In every relationship, we take comfort in a certain level of routine as a way of knowing what we can count on the other person in the relationship. Such predictability provides a sense of comfort and security. However, it requires balance with novelty to avoid boredom. An example of balance might be friends who get together every Saturday for brunch, but make a commitment to always try new restaurants each week. - Openness-Closedness:

refers to the desire to be open and honest with others while at the same time not wanting to reveal everything about yourself to someone else. One’s desire for privacy does not mean they are shutting out others. It is a normal human need. We tend to disclose the most personal information to those with whom we have the closest relationships. However, even these people do not know everything about us. As the old saying goes, “We all have skeletons in our closet,” and that’s okay.

It’s important to note that these dialectics are dynamic and that our needs change over time. At times, we may even hold what appear to be contradictory needs. Relationship dissatisfaction is caused when our needs are not being met in a relationship, or when the other person falls on the opposite end of the continuum. For example, if you fall higher on the autonomy end of the continuum and your romantic partner falls higher on the connection end, you may end up feeling smothered or think that the other person is ‘clingy.’ Conversely, the other person may feel like you never want to spend time with them and thus are not as interested in the relationship as they are. Because negative feelings and miscommunication can arise as a result of dialectical imbalances, managing dialectics in a relationship is key. In the Communication Competence section of this chapter, we will discuss some techniques for how to better manage dialectics in relationships to increase relationship satisfaction.

8.2.4: Deteriorating Stage

In the deteriorating stage, relationships start to decline and may eventually be terminated. Typically, in this stage, people may start to avoid the other person, decrease communication with them, or engage in increased conflict (Verderber & Verderber, 2013). During this stage, Knapp’s Stages of Relational Interaction can help us better understand how relationships deteriorate and/or terminate. While the theory covers both stages of coming together and stages of coming apart, we only focus here on the latter: Differentiating, Circumscribing, Stagnating, Avoiding, and Terminating.

8.2.4.1: Differentiating:

Differentiating is a process of disengaging or uncoupling; differences between the relationship partners are emphasized, and what was thought to be similar begins to disintegrate. Instead of working together, partners quickly begin to become more individualistic in their attitudes. Conflict is a common form of communication during this stage and oftentimes it acts as a way to test how much the other can tolerate something that may threaten the relationship.

8.2.4.2: Circumscribing:

To circumscribe means to draw a line around something or put a boundary around it (Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2011). So when someone circumscribes, communication decreases and certain areas or subjects become restricted as individuals verbally close themselves off from each other. They may say things like “I don’t want to talk about that anymore” or “You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.”

8.2.4.3: Stagnating:

When a relationship has stagnated, it has come to a standstill, as individuals basically wait for the relationship to end. Outward communication may be avoided, but internal communication may be frequent. The relational conflict flaw of mindreading takes place as a person’s internal thoughts lead them to avoid communication. For example, a person may think, “There’s no need to bring this up again, because I know exactly how he’ll react!” This stage can be prolonged in some relationships, and some people may linger here because they don’t know how to end the relationship, want to avoid potential pain from termination, or may still hope to rekindle the spark that started the relationship.

8.2.4.4: Avoiding:

In this stage, as the name implies, when people engage in avoidance, they try to physically avoid each other. For example, you may decide not to go to a specific social gathering when you know that other person will be there. However, when actual physical avoidance cannot take place, people will simply avoid each other while they’re together and treat the other as if they don’t exist. When avoiding, the individuals in the relationship become separate from one another physically, emotionally, and mentally. When there is communication, it is often marked by antagonism or unfriendliness (“I just don’t want to see or talk to you”).[4] In addition to not spending time with one another, they both begin to avoid the other person’s needs and start to focus solely on themselves.

8.2.4.5: Terminating:

The terminating of a relationship can occur shortly after a relationship begins or after twenty-year relational history has been established. Termination can result from outside circumstances such as geographic separation or internal factors such as changing values or personalities that lead to a weakening of the bond. Termination exchanges involve some typical communicative elements and may begin with a summary message that recaps the relationship and provides a reason for the termination (e.g., “We’ve had some ups and downs over our three years together, but I’m getting ready to go to college, and I want to be free to explore who I am.”). The summary message may be followed by a distance message that further communicates the relational drift that has occurred (e.g., “We’ve really grown apart over the past year”), which may be followed by a disassociation message that prepares people to be apart by projecting what happens after the relationship ends (e.g., “I know you’ll do fine without me. You can use this time to explore your options and figure out if you want to go to college too or not.”).

Finally, there is often a message regarding the possibility for future communication in the relationship (e.g., “I think it would be best if we don’t see each other for the first few months, but text me if you want to.”) (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009). However, people also often engage in negative termination strategies such as yelling, blaming the other person, or ghosting, which is “the practice of suddenly ending all contact with a person without explanation (Dictionary.com).”