Muscle Tissue

Figure 10.1 Tennis Player Athletes rely on toned skeletal muscles to supply the force required for movement. (credit: Emmanuel Huybrechts/flickr)

Chapter Objectives

After studying this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain the organization of muscle tissue

- Describe the function and structure of skeletal, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle

- Explain how muscles work with tendons to move the body

- Describe how muscles contract and relax

- Define the process of muscle metabolism

- Explain how the nervous system controls muscle tension

- Relate the connections between exercise and muscle performance

Introduction

When most people think of muscles, they think of the muscles that are visible just under the skin, particularly of the limbs. These are skeletal muscles, so-named because most of them move the skeleton. But there are two other types of muscle in the body, with distinctly different jobs. Cardiac muscle, found in the heart, is concerned with pumping blood through the circulatory system. Smooth muscle is concerned with various involuntary movements, such as having one’s hair stand on end when cold or frightened, or moving food through the digestive system. This chapter will examine the structure and function of these three types of muscles.

Overview of Muscle Tissues

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the different types of muscle

- Explain contractibility and extensibility

Muscle is one of the four primary tissue types of the body, and the body contains three types of muscle tissue: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle (Figure 10.2). All three muscle tissues have some properties in common; they all exhibit a quality called excitability as their plasma membranes can change their electrical states (from polarized to depolarized) and send an electrical wave called an action potential along the entire length of the membrane. While the nervous system can influence the excitability of cardiac and smooth muscle to some degree, skeletal muscle completely depends on signaling from the nervous system to work properly. On the other hand, both cardiac muscle and smooth muscle can respond to other stimuli, such as hormones and local stimuli.

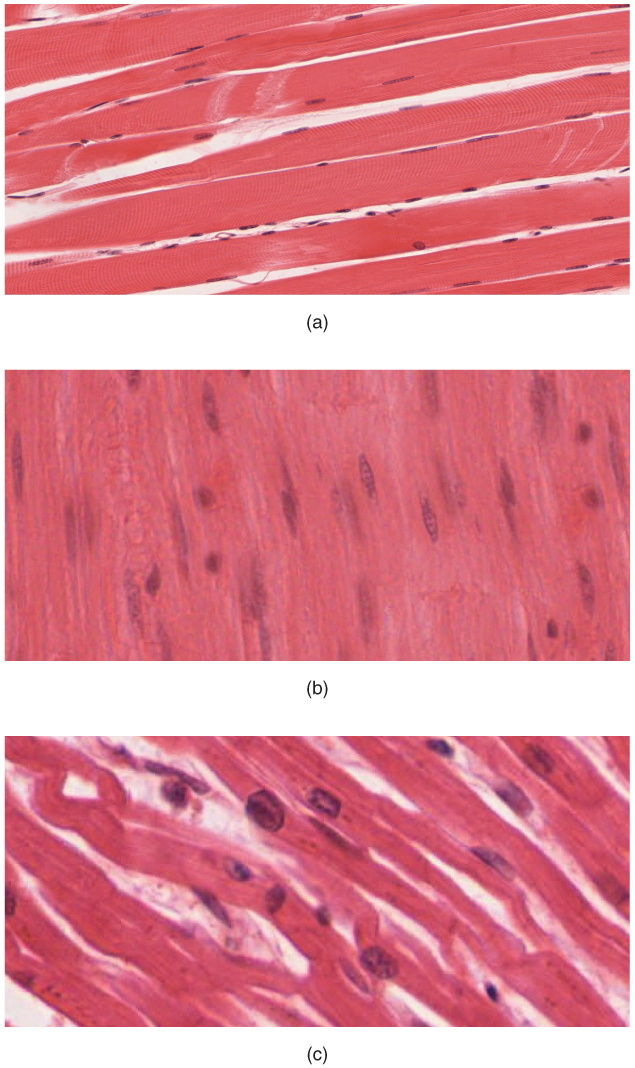

Figure 10.2 The Three Types of Muscle Tissue The body contains three types of muscle tissue: (a) skeletal muscle, (b) smooth muscle, and (c) cardiac muscle. (Micrographs provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

The muscles all begin the actual process of contracting (shortening) when a protein called actin is pulled by a protein called myosin. This occurs in striated muscle (skeletal and cardiac) after specific binding sites on the actin have been exposed in response to the interaction between calcium ions (Ca++) and proteins (troponin and tropomyosin) that “shield” the actin-binding sites. Ca++ also is required for the contraction of smooth muscle, although its role is different: here Ca++ activates enzymes, which in turn activate myosin heads. All muscles require adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to continue the process of contracting, and they all relax when the Ca++ is removed and the actin-binding sites are re-shielded.

A muscle can return to its original length when relaxed due to a quality of muscle tissue called elasticity. It can recoil back to its original length due to elastic fibers. Muscle tissue also has the quality of extensibility; it can stretch or extend. Contractility allows muscle tissue to pull on its attachment points and shorten with force.

Differences among the three muscle types include the microscopic organization of their contractile proteins—actin and myosin. The actin and myosin proteins are arranged very regularly in the cytoplasm of individual muscle cells (referred to as fibers) in both skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle, which creates a pattern, or stripes, called striations. The striations are visible with a light microscope under high magnification (see Figure 10.2). Skeletal muscle fibers are multinucleated structures that compose the skeletal muscle. Cardiac muscle fibers each have one to two nuclei and are physically and electrically connected to each other so that the entire heart contracts as one unit (called a syncytium).

Because the actin and myosin are not arranged in such regular fashion in smooth muscle, the cytoplasm of a smooth muscle fiber (which has only a single nucleus) has a uniform, nonstriated appearance (resulting in the name smooth muscle). However, the less organized appearance of smooth muscle should not be interpreted as less efficient. Smooth muscle in the walls of arteries is a critical component that regulates blood pressure necessary to push blood through the circulatory system; and smooth muscle in the skin, visceral organs, and internal passageways is essential for moving all materials through the body.

Skeletal Muscle

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the layers of connective tissues packaging skeletal muscle

- Explain how muscles work with tendons to move the body

- Identify areas of the skeletal muscle fibers

- Describe excitation-contraction coupling

The best-known feature of skeletal muscle is its ability to contract and cause movement. Skeletal muscles act not only to produce movement but also to stop movement, such as resisting gravity to maintain posture. Small, constant adjustments of the skeletal muscles are needed to hold a body upright or balanced in any position. Muscles also prevent excess movement of the bones and joints, maintaining skeletal stability and preventing skeletal structure damage or deformation. Joints can become misaligned or dislocated entirely by pulling on the associated bones; muscles work to keep joints stable. Skeletal muscles are located throughout the body at the openings of internal tracts to control the movement of various substances. These muscles allow functions, such as swallowing, urination, and defecation, to be under voluntary control. Skeletal muscles also protect internal organs (particularly abdominal and pelvic organs) by acting as an external barrier or shield to external trauma and by supporting the weight of the organs.

Skeletal muscles contribute to the maintenance of homeostasis in the body by generating heat. Muscle contraction requires energy, and when ATP is broken down, heat is produced. This heat is very noticeable during exercise, when sustained muscle movement causes body temperature to rise, and in cases of extreme cold, when shivering produces random skeletal muscle contractions to generate heat.

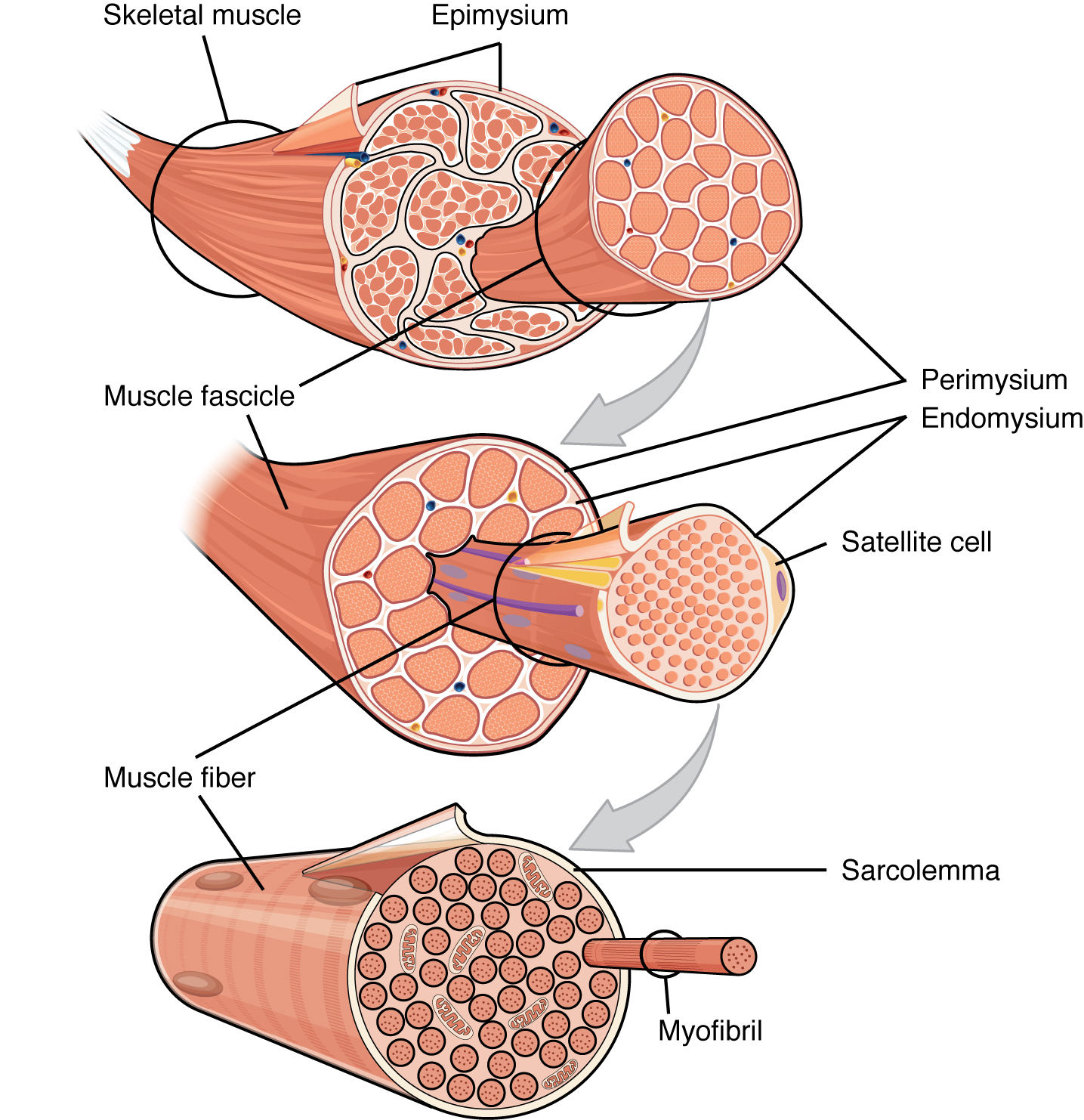

Each skeletal muscle is an organ that consists of various integrated tissues. These tissues include the skeletal muscle fibers, blood vessels, nerve fibers, and connective tissue. Each skeletal muscle has three layers of connective tissue (called “mysia”) that enclose it and provide structure to the muscle as a whole, and also compartmentalize the muscle fibers within the muscle (Figure 10.3). Each muscle is wrapped in a sheath of dense, irregular connective tissue called the epimysium, which allows a muscle to contract and move powerfully while maintaining its structural integrity. The epimysium also separates muscle from other tissues and organs in the area, allowing the muscle to move independently.

Figure 10.3 The Three Connective Tissue Layers Bundles of muscle fibers, called fascicles, are covered by the perimysium. Muscle fibers are covered by the endomysium.

Inside each skeletal muscle, muscle fibers are organized into individual bundles, each called a fascicle, by a middle layer of connective tissue called the perimysium. This fascicular organization is common in muscles of the limbs; it allows the nervous system to trigger a specific movement of a muscle by activating a subset of muscle fibers within a bundle, or fascicle of the muscle. Inside each fascicle, each muscle fiber is encased in a thin connective tissue layer of collagen and reticular fibers called the endomysium. The endomysium contains the extracellular fluid and nutrients to support the muscle fiber. These nutrients are supplied via blood to the muscle tissue.

In skeletal muscles that work with tendons to pull on bones, the collagen in the three tissue layers (the mysia) intertwines with the collagen of a tendon. At the other end of the tendon, it fuses with the periosteum coating the bone. The tension created by contraction of the muscle fibers is then transferred though the mysia, to the tendon, and then to the periosteum to pull on the bone for movement of the skeleton. In other places, the mysia may fuse with a broad, tendon-like sheet called an aponeurosis, or to fascia, the connective tissue between skin and bones. The broad sheet of connective tissue in the lower back that the latissimus dorsi muscles (the “lats”) fuse into is an example of an aponeurosis.

Every skeletal muscle is also richly supplied by blood vessels for nourishment, oxygen delivery, and waste removal. In addition, every muscle fiber in a skeletal muscle is supplied by the axon branch of a somatic motor neuron, which signals the fiber to contract. Unlike cardiac and smooth muscle, the only way to functionally contract a skeletal muscle is through signaling from the nervous system.

Skeletal Muscle Fibers

Because skeletal muscle cells are long and cylindrical, they are commonly referred to as muscle fibers. Skeletal muscle fibers can be quite large for human cells, with diameters up to 100 μm and lengths up to 30 cm (11.8 in) in the Sartorius of the upper leg. During early development, embryonic myoblasts, each with its own nucleus, fuse with up to hundreds of other myoblasts to form the multinucleated skeletal muscle fibers. Multiple nuclei mean multiple copies of genes, permitting the production of the large amounts of proteins and enzymes needed for muscle contraction.

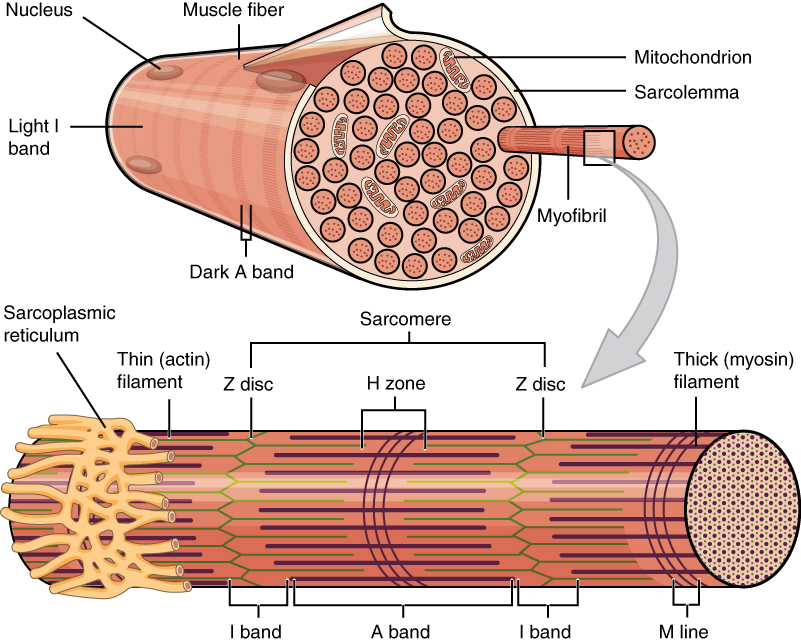

Some other terminology associated with muscle fibers is rooted in the Greek sarco, which means “flesh.” The plasma membrane of muscle fibers is called the sarcolemma, the cytoplasm is referred to as sarcoplasm, and the specialized smooth endoplasmic reticulum, which stores, releases, and retrieves calcium ions (Ca++) is called the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (Figure 10.4). As will soon be described, the functional unit of a skeletal muscle fiber is the sarcomere, a highly organized arrangement of the contractile myofilaments actin (thin filament) and myosin (thick filament), along with other support proteins.

Figure 10.4 Muscle Fiber A skeletal muscle fiber is surrounded by a plasma membrane called the sarcolemma, which contains sarcoplasm, the cytoplasm of muscle cells. A muscle fiber is composed of many fibrils, which give the cell its striated appearance.

The Sarcomere

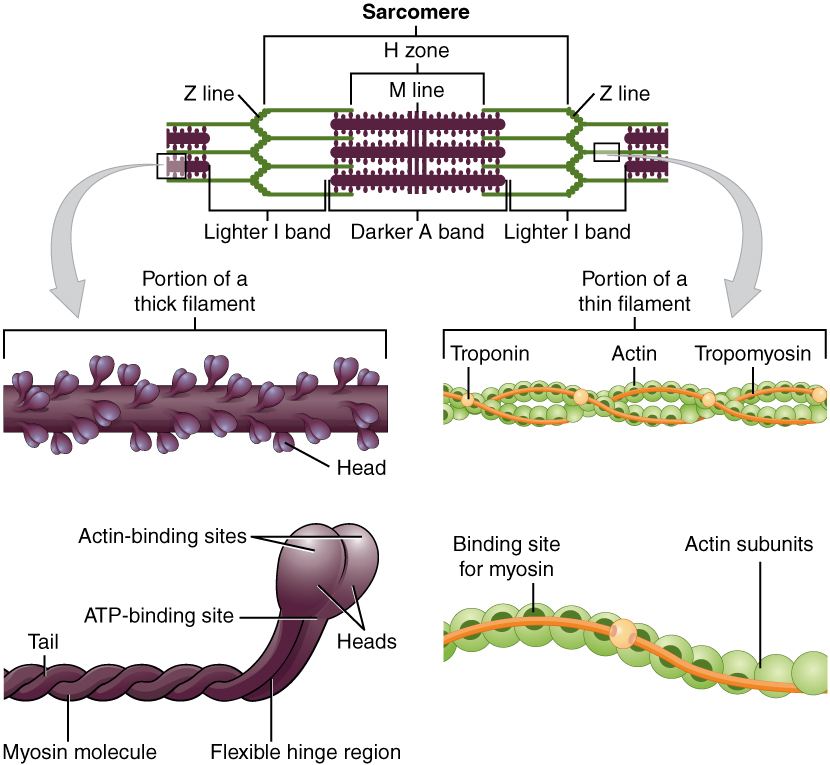

The striated appearance of skeletal muscle fibers is due to the arrangement of the myofilaments of actin and myosin in sequential order from one end of the muscle fiber to the other. Each packet of these microfilaments and their regulatory proteins, troponin and tropomyosin (along with other proteins) is called a sarcomere.

Interactive Link

Watch this video to learn more about macro- and microstructures of skeletal muscles. (a) What are the names of the “junction points” between sarcomeres? (b) What are the names of the “subunits” within the myofibrils that run the length of skeletal muscle fibers? (c) What is the “double strand of pearls” described in the video? (d) What gives a skeletal muscle fiber its striated appearance?

The sarcomere is the functional unit of the muscle fiber. The sarcomere itself is bundled within the myofibril that runs the entire length of the muscle fiber and attaches to the sarcolemma at its end. As myofibrils contract, the entire muscle cell contracts. Because myofibrils are only approximately 1.2 μm in diameter, hundreds to thousands (each with thousands of sarcomeres) can be found inside one muscle fiber. Each sarcomere is approximately 2 μm in length with a three-dimensional cylinder-like arrangement and is bordered by structures called Z-discs (also called Z-lines, because pictures are two-dimensional), to which the actin myofilaments are anchored (Figure 10.5). Because the actin and its troponin-tropomyosin complex (projecting from the Z-discs toward the center of the sarcomere) form strands that are thinner than the myosin, it is called the thin filament of the sarcomere. Likewise, because the myosin strands and their multiple heads (projecting from the center of the sarcomere, toward but not all to way to, the Z-discs) have more mass and are thicker, they are called the thick filament of the sarcomere.

Figure 10.5 The Sarcomere The sarcomere, the region from one Z-line to the next Z-line, is the functional unit of a skeletal muscle fiber.

The Neuromuscular Junction

Another specialization of the skeletal muscle is the site where a motor neuron’s terminal meets the muscle fiber—called the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). This is where the muscle fiber first responds to signaling by the motor neuron. Every skeletal muscle fiber in every skeletal muscle is innervated by a motor neuron at the NMJ. Excitation signals from the neuron are the only way to functionally activate the fiber to contract.

Interactive Link

Every skeletal muscle fiber is supplied by a motor neuron at the NMJ. Watch this video to learn more about what happens at the NMJ. (a) What is the definition of a motor unit? (b) What is the structural and functional difference between a large motor unit and a small motor unit? (c) Can you give an example of each? (d) Why is the neurotransmitter acetylcholine degraded after binding to its receptor?

Excitation-Contraction Coupling

All living cells have membrane potentials, or electrical gradients across their membranes. The inside of the membrane is usually around -60 to -90 mV, relative to the outside. This is referred to as a cell’s membrane potential. Neurons and muscle cells can use their membrane potentials to generate electrical signals. They do this by controlling the movement of charged particles, called ions, across their membranes to create electrical currents. This is achieved by opening and closing specialized proteins in the membrane called ion channels. Although the currents generated by ions moving through these channel proteins are very small, they form the basis of both neural signaling and muscle contraction.

Both neurons and skeletal muscle cells are electrically excitable, meaning that they are able to generate action potentials. An action potential is a special type of electrical signal that can travel along a cell membrane as a wave. This allows a signal to be transmitted quickly and faithfully over long distances.

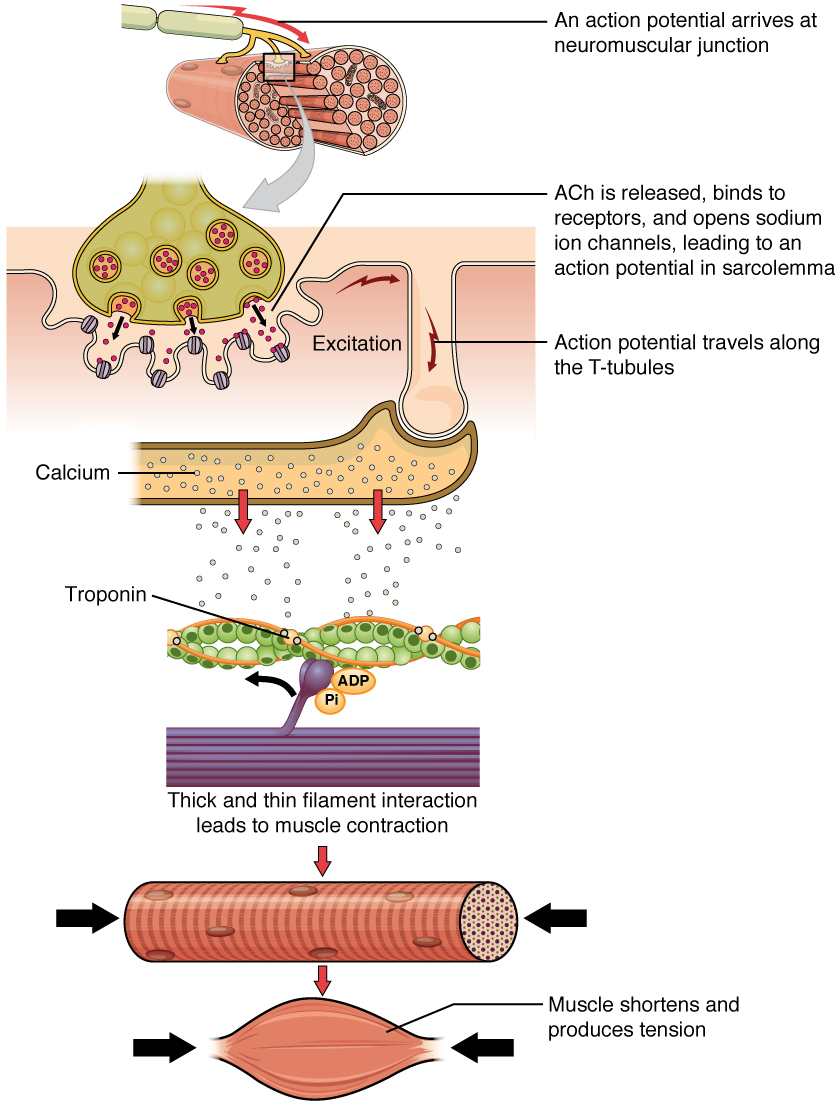

Although the term excitation-contraction coupling confuses or scares some students, it comes down to this: for a skeletal muscle fiber to contract, its membrane must first be “excited”—in other words, it must be stimulated to fire an action potential. The muscle fiber action potential, which sweeps along the sarcolemma as a wave, is “coupled” to the actual contraction through the release of calcium ions (Ca++) from the SR. Once released, the Ca++ interacts with the shielding proteins, forcing them to move aside so that the actin-binding sites are available for attachment by myosin heads. The myosin then pulls the actin filaments toward the center, shortening the muscle fiber.

In skeletal muscle, this sequence begins with signals from the somatic motor division of the nervous system. In other words, the “excitation” step in skeletal muscles is always triggered by signaling from the nervous system (Figure 10.6).

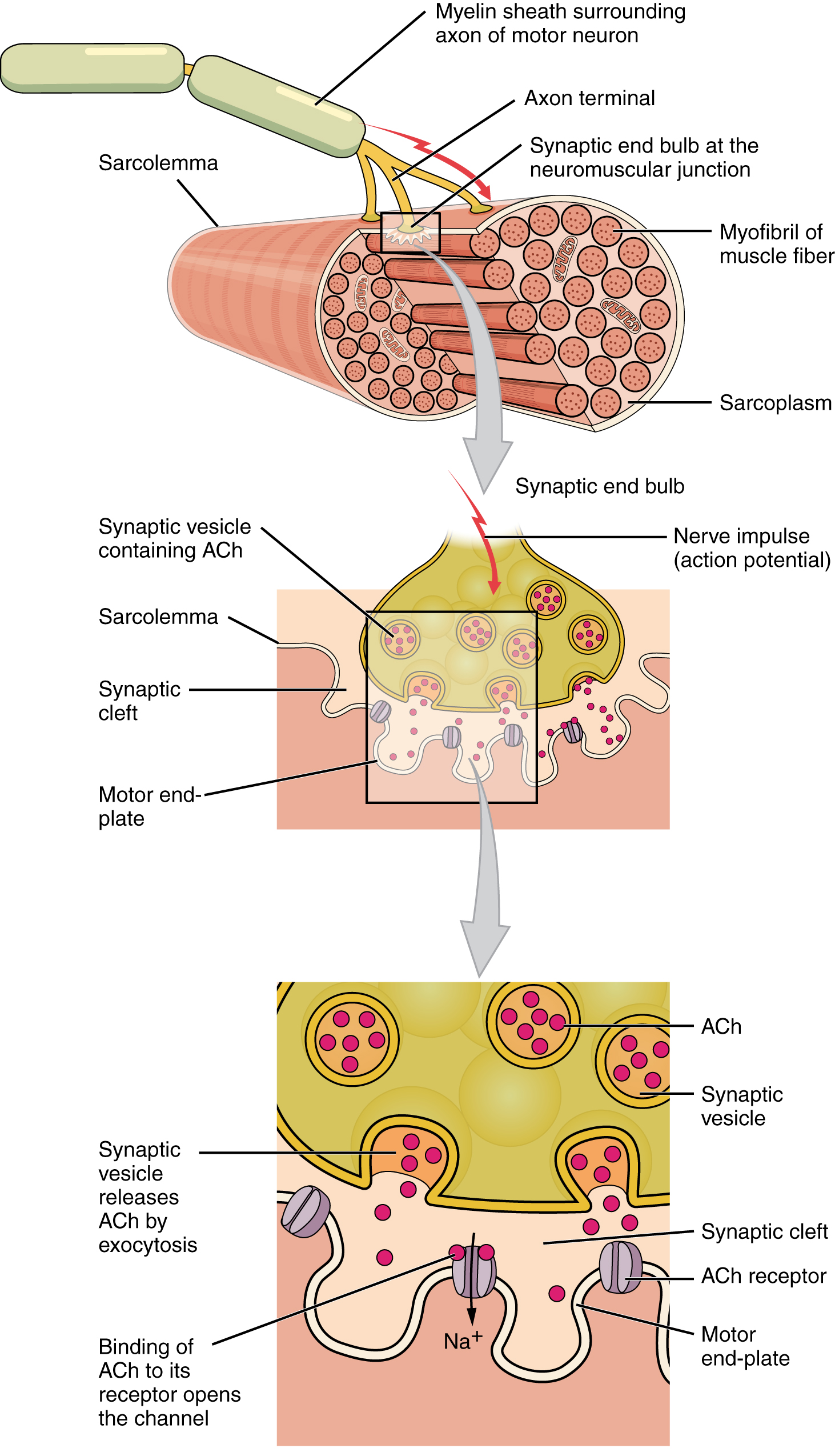

Figure 10.6 Motor End-Plate and Innervation At the NMJ, the axon terminal releases ACh. The motor end-plate is the location of the ACh-receptors in the muscle fiber sarcolemma. When ACh molecules are released, they diffuse across a minute space called the synaptic cleft and bind to the receptors.

The motor neurons that tell the skeletal muscle fibers to contract originate in the spinal cord, with a smaller number located in the brainstem for activation of skeletal muscles of the face, head, and neck. These neurons have long processes, called axons, which are specialized to transmit action potentials long distances— in this case, all the way from the spinal cord to the muscle itself (which may be up to three feet away). The axons of multiple neurons bundle together to form nerves, like wires bundled together in a cable.

Signaling begins when a neuronal action potential travels along the axon of a motor neuron, and then along the individual branches to terminate at the NMJ. At the NMJ, the axon terminal releases a chemical messenger, or neurotransmitter, called acetylcholine (ACh). The ACh molecules diffuse across a minute space called the synaptic cleft and bind to ACh receptors located within the motor end-plate of the sarcolemma on the other side of the synapse. Once ACh binds, a channel in the ACh receptor opens and positively charged ions can pass through into the muscle fiber, causing it to depolarize, meaning that the membrane potential of the muscle fiber becomes less negative (closer to zero.)

As the membrane depolarizes, another set of ion channels called voltage-gated sodium channels are triggered to open. Sodium ions enter the muscle fiber, and an action potential rapidly spreads (or “fires”) along the entire membrane to initiate excitation-contraction coupling.

Things happen very quickly in the world of excitable membranes (just think about how quickly you can snap your fingers as soon as you decide to do it). Immediately following depolarization of the membrane, it repolarizes, re-establishing the negative membrane potential. Meanwhile, the ACh in the synaptic cleft is degraded by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) so that the ACh cannot rebind to a receptor and reopen its channel, which would cause unwanted extended muscle excitation and contraction.

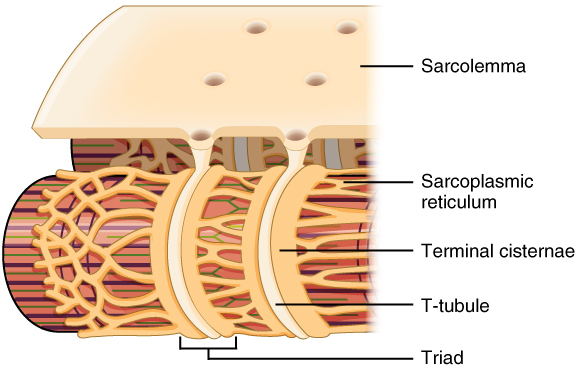

Propagation of an action potential along the sarcolemma is the excitation portion of excitation-contraction coupling. Recall that this excitation actually triggers the release of calcium ions (Ca++) from its storage in the cell’s SR. For the action potential to reach the membrane of the SR, there are periodic invaginations in the sarcolemma, called T-tubules (“T” stands for “transverse”). You will recall that the diameter of a muscle fiber can be up to 100 μm, so these T-tubules ensure that the membrane can get close to the SR in the sarcoplasm. The arrangement of a T-tubule with the membranes of SR on either side is called a triad (Figure 10.7). The triad surrounds the cylindrical structure called a myofibril, which contains actin and myosin.

Figure 10.7 The T-tubule Narrow T-tubules permit the conduction of electrical impulses. The SR functions to regulate intracellular levels of calcium. Two terminal cisternae (where enlarged SR connects to the T-tubule) and one T-tubule comprise a triad—a “threesome” of membranes, with those of SR on two sides and the T-tubule sandwiched between them.

The T-tubules carry the action potential into the interior of the cell, which triggers the opening of calcium channels in the membrane of the adjacent SR, causing Ca++ to diffuse out of the SR and into the sarcoplasm. It is the arrival of Ca++ in the sarcoplasm that initiates contraction of the muscle fiber by its contractile units, or sarcomeres.

Muscle Fiber Contraction and Relaxation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the components involved in a muscle contraction

- Explain how muscles contract and relax

- Describe the sliding filament model of muscle contraction

The sequence of events that result in the contraction of an individual muscle fiber begins with a signal—the neurotransmitter, ACh—from the motor neuron innervating that fiber. The local membrane of the fiber will depolarize as positively charged sodium ions (Na+) enter, triggering an action potential that spreads to the rest of the membrane which will depolarize, including the T-tubules. This triggers the release of calcium ions (Ca++) from storage in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). The Ca++ then initiates contraction, which is sustained by ATP (Figure 10.8). As long as Ca++ ions remain in the sarcoplasm to bind to troponin, which keeps the actin-binding sites “unshielded,” and as long as ATP is available to drive the cross-bridge cycling and the pulling of actin strands by myosin, the muscle fiber will continue to shorten to an anatomical limit.

Figure 10.8 Contraction of a Muscle Fiber A cross-bridge forms between actin and the myosin heads triggering contraction. As long as Ca++ ions remain in the sarcoplasm to bind to troponin, and as long as ATP is available, the muscle fiber will continue to shorten.

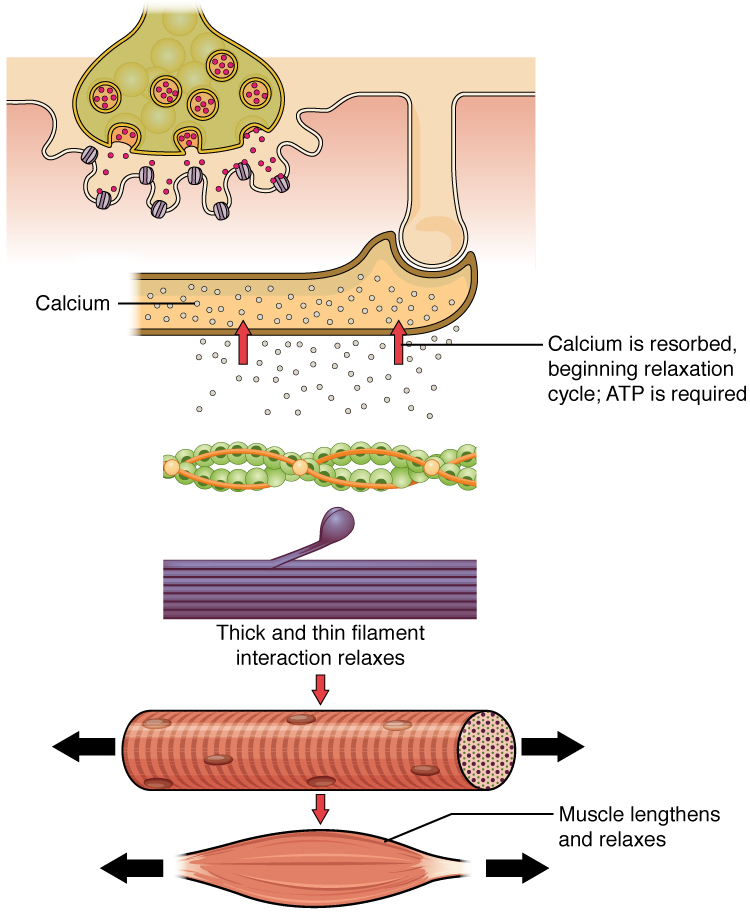

Muscle contraction usually stops when signaling from the motor neuron ends, which repolarizes the sarcolemma and T-tubules, and closes the voltage-gated calcium channels in the SR. Ca++ ions are then pumped back into the SR, which causes the tropomyosin to reshield (or re-cover) the binding sites on the actin strands. A muscle also can stop contracting when it runs out of ATP and becomes fatigued (Figure 10.9).

Figure 10.9 Relaxation of a Muscle Fiber Ca++ ions are pumped back into the SR, which causes the tropomyosin to reshield the binding sites on the actin strands. A muscle may also stop contracting when it runs out of ATP and becomes fatigued.

Interactive Link

The release of calcium ions initiates muscle contractions. Watch this video to learn more about the role of calcium. (a) What are “T-tubules” and what is their role? (b) Please describe how actin-binding sites are made available for cross-bridging with myosin heads during contraction.

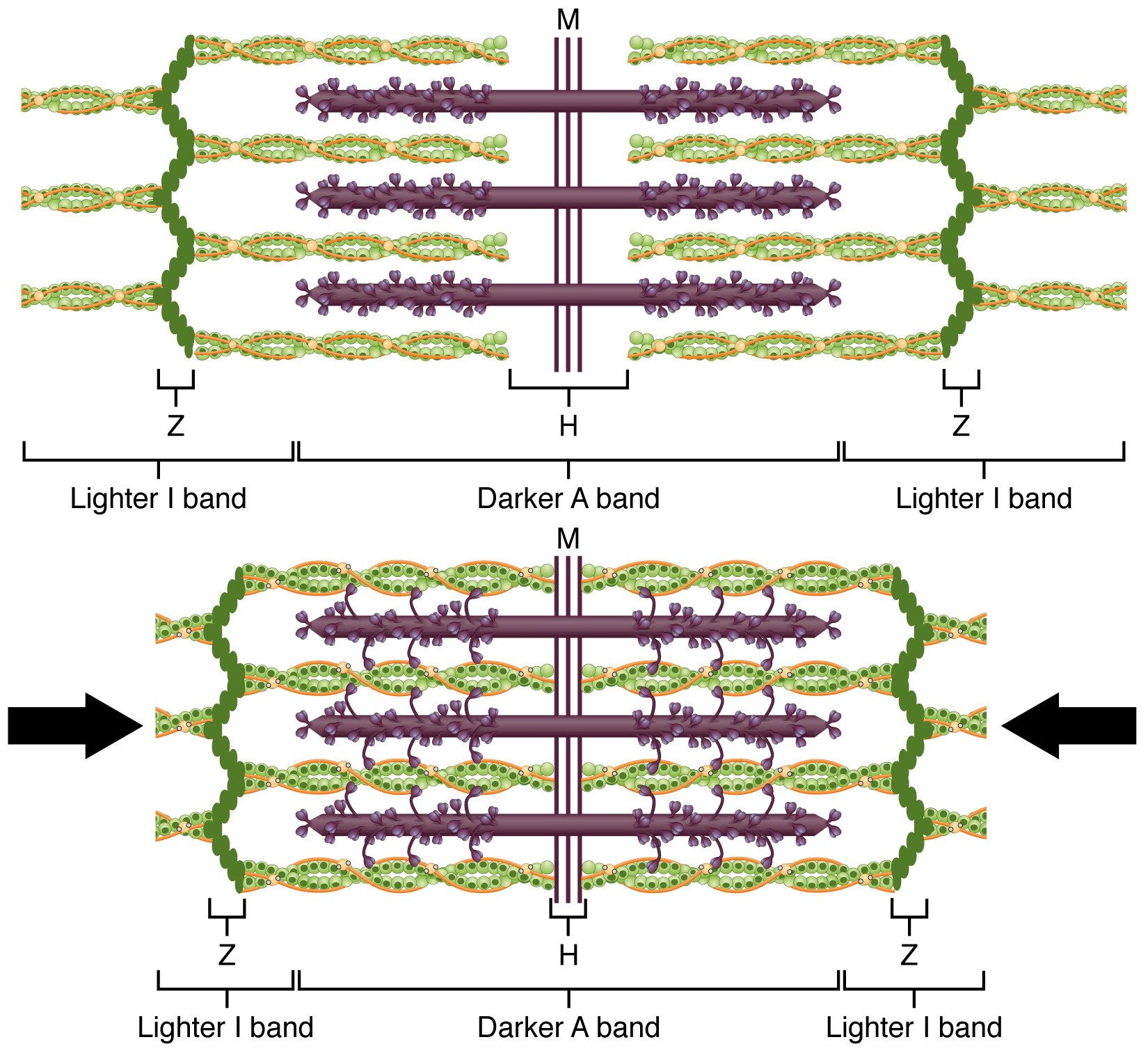

The molecular events of muscle fiber shortening occur within the fiber’s sarcomeres (see Figure 10.10). The contraction of a striated muscle fiber occurs as the sarcomeres, linearly arranged within myofibrils, shorten as myosin heads pull on the actin filaments.

The region where thick and thin filaments overlap has a dense appearance, as there is little space between the filaments. This zone where thin and thick filaments overlap is very important to muscle contraction, as it is the site where filament movement starts. Thin filaments, anchored at their ends by the Z-discs, do not extend completely into the central region that only contains thick filaments, anchored at their bases at a spot called the M-line. A myofibril is composed of many sarcomeres running along its length; thus, myofibrils and muscle cells contract as the sarcomeres contract.

The Sliding Filament Model of Contraction

When signaled by a motor neuron, a skeletal muscle fiber contracts as the thin filaments are pulled and then slide past the thick filaments within the fiber’s sarcomeres. This process is known as the sliding filament model of muscle contraction (Figure 10.10). The sliding can only occur when myosin-binding sites on the actin filaments are exposed by a series of steps that begins with Ca++ entry into the sarcoplasm.

Figure 10.10 The Sliding Filament Model of Muscle Contraction When a sarcomere contracts, the Z lines move closer together, and the I band becomes smaller. The A band stays the same width. At full contraction, the thin and thick filaments overlap completely.

Tropomyosin is a protein that winds around the chains of the actin filament and covers the myosin-binding sites to prevent actin from binding to myosin. Tropomyosin binds to troponin to form a troponin-tropomyosin complex. The troponin-tropomyosin complex prevents the myosin “heads” from binding to the active sites on the actin microfilaments. Troponin also has a binding site for Ca++ ions.

To initiate muscle contraction, tropomyosin has to expose the myosin-binding site on an actin filament to allow cross-bridge formation between the actin and myosin microfilaments. The first step in the process of contraction is for Ca++ to bind to troponin so that tropomyosin can slide away from the binding sites on the actin strands. This allows the myosin heads to bind to these exposed binding sites and form cross-bridges. The thin filaments are then pulled by the myosin heads to slide past the thick filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. But each head can only pull a very short distance before it has reached its limit and must be “re-cocked” before it can pull again, a step that requires ATP.

ATP and Muscle Contraction

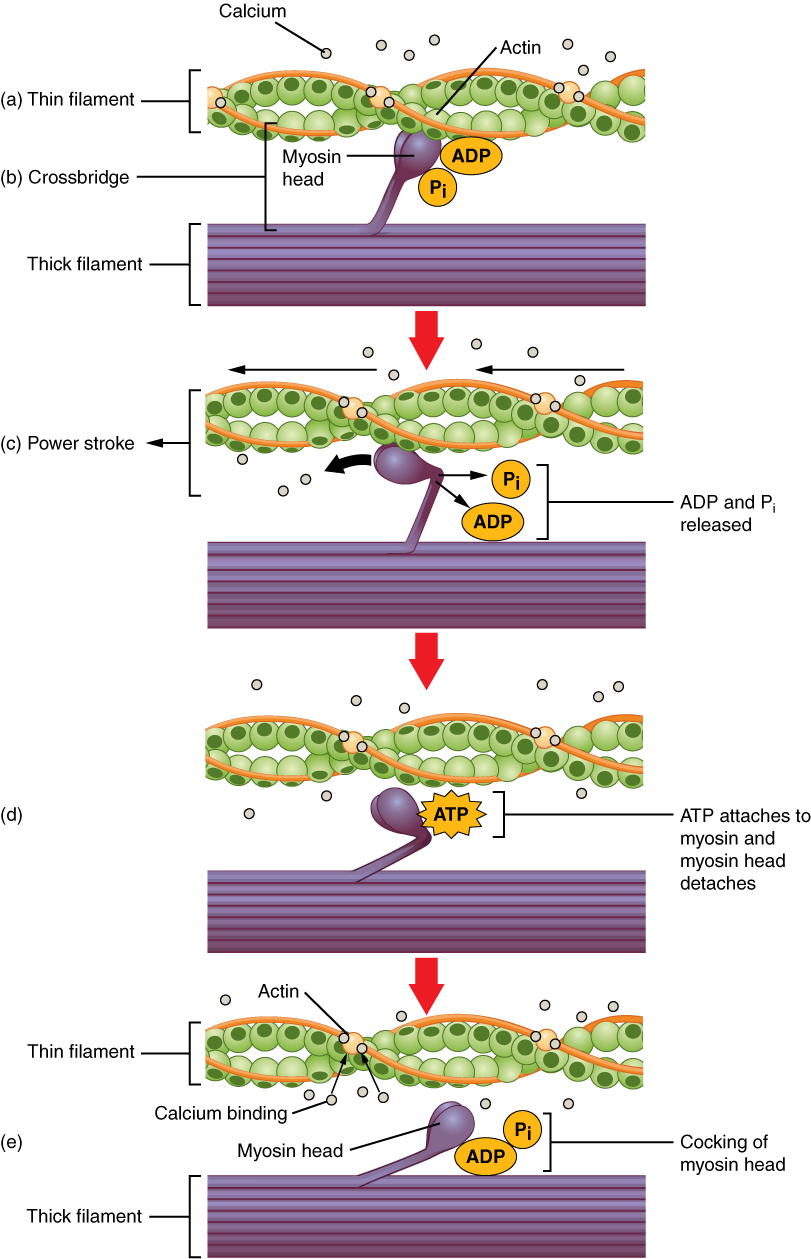

For thin filaments to continue to slide past thick filaments during muscle contraction, myosin heads must pull the actin at the binding sites, detach, re-cock, attach to more binding sites, pull, detach, re-cock, etc. This repeated movement is known as the cross-bridge cycle. This motion of the myosin heads is similar to the oars when an individual rows a boat: The paddle of the oars (the myosin heads) pull, are lifted from the water (detach), repositioned (re-cocked) and then immersed again to pull (Figure 10.11). Each cycle requires energy, and the action of the myosin heads in the sarcomeres repetitively pulling on the thin filaments also requires energy, which is provided by ATP.

Figure 10.11 Skeletal Muscle Contraction (a) The active site on actin is exposed as calcium binds to troponin. (b) The myosin head is attracted to actin, and myosin binds actin at its actin-binding site, forming the cross-bridge. (c) During the power stroke, the phosphate generated in the previous contraction cycle is released. This results in the myosin head pivoting toward the center of the sarcomere, after which the attached ADP and phosphate group are released. (d) A new molecule of ATP attaches to the myosin head, causing the cross-bridge to detach. (e) The myosin head hydrolyzes ATP to ADP and phosphate, which returns the myosin to the cocked position.

Cross-bridge formation occurs when the myosin head attaches to the actin while adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi) are still bound to myosin (Figure 10.11a,b). Pi is then released, causing myosin to form a stronger attachment to the actin, after which the myosin head moves toward the M-line, pulling the actin along with it. As actin is pulled, the filaments move approximately 10 nm toward the M-line. This movement is called the power stroke, as movement of the thin filament occurs at this step (Figure 10.11c). In the absence of ATP, the myosin head will not detach from actin.

One part of the myosin head attaches to the binding site on the actin, but the head has another binding site for ATP. ATP binding causes the myosin head to detach from the actin (Figure 10.11d). After this occurs, ATP is converted to ADP and Pi by the intrinsic ATPase activity of myosin. The energy released during ATP hydrolysis changes the angle of the myosin head into a cocked position (Figure 10.11e). The myosin head is now in position for further movement.

When the myosin head is cocked, myosin is in a high-energy configuration. This energy is expended as the myosin head moves through the power stroke, and at the end of the power stroke, the myosin head is in a low-energy position. After the power stroke, ADP is released; however, the formed cross-bridge is still in place, and actin and myosin are bound together. As long as ATP is available, it readily attaches to myosin, the cross-bridge cycle can recur, and muscle contraction can continue.

Note that each thick filament of roughly 300 myosin molecules has multiple myosin heads, and many cross-bridges form and break continuously during muscle contraction. Multiply this by all of the sarcomeres in one myofibril, all the myofibrils in one muscle fiber, and all of the muscle fibers in one skeletal muscle, and you can understand why so much energy (ATP) is needed to keep skeletal muscles working. In fact, it is the loss of ATP that results in the rigor mortis observed soon after someone dies. With no further ATP production possible, there is no ATP available for myosin heads to detach from the actin-binding sites, so the cross-bridges stay in place, causing the rigidity in the skeletal muscles.

Sources of ATP

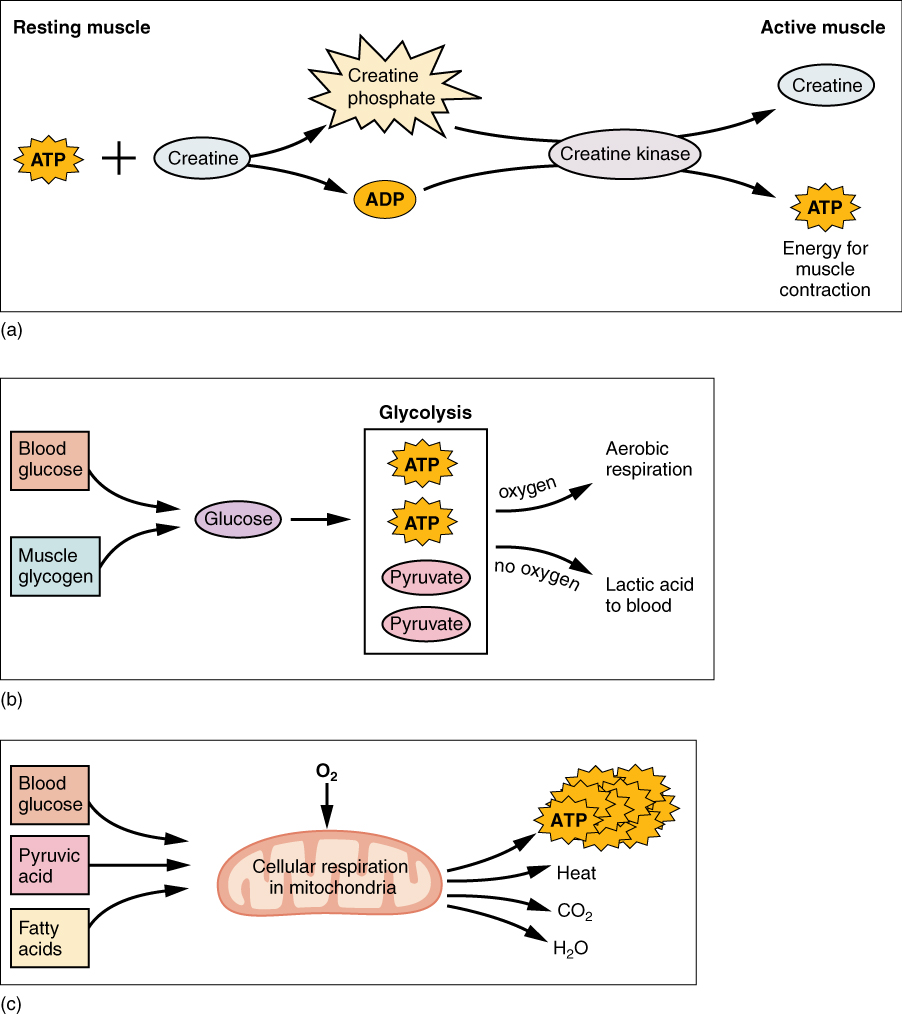

ATP supplies the energy for muscle contraction to take place. In addition to its direct role in the cross-bridge cycle, ATP also provides the energy for the active-transport Ca++ pumps in the SR. Muscle contraction does not occur without sufficient amounts of ATP. The amount of ATP stored in muscle is very low, only sufficient to power a few seconds worth of contractions. As it is broken down, ATP must therefore be regenerated and replaced quickly to allow for sustained contraction. There are three mechanisms by which ATP can be regenerated in muscle cells: creatine phosphate metabolism, anaerobic glycolysis, and aerobic respiration.

Creatine phosphate is a molecule that can store energy in its phosphate bonds. In a resting muscle, excess ATP transfers its energy to creatine, producing ADP and creatine phosphate. This acts as an energy reserve that can be used to quickly create more ATP. When the muscle starts to contract and needs energy, creatine phosphate transfers its phosphate back to ADP to form ATP and creatine. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme creatine kinase and occurs very quickly; thus, creatine phosphate-derived ATP powers the first few seconds of muscle contraction. However, creatine phosphate can only provide approximately 15 seconds worth of energy, at which point another energy source has to be used (Figure 10.12).

Figure 10.12 Muscle Metabolism (a) Some ATP is stored in a resting muscle. As contraction starts, it is used up in seconds. More ATP is generated from creatine phosphate for about 15 seconds. (b) Each glucose molecule produces two ATP and two molecules of pyruvic acid, which can be used in aerobic respiration or converted to lactic acid. If oxygen is not available, pyruvic acid is converted to lactic acid, which may contribute to muscle fatigue. This occurs during strenuous exercise when high amounts of energy are needed but oxygen cannot be sufficiently delivered to muscle. (c) Aerobic respiration is the breakdown of glucose in the presence of oxygen (O2) to produce carbon dioxide, water, and ATP. Approximately 95 percent of the ATP required for resting or moderately active muscles is provided by aerobic respiration, which takes place in mitochondria.

As the ATP produced by creatine phosphate is depleted, muscles turn to glycolysis as an ATP source. Glycolysis is an anaerobic (non-oxygen-dependent) process that breaks down glucose (sugar) to produce ATP; however, glycolysis cannot generate ATP as quickly as creatine phosphate. Thus, the switch to glycolysis results in a slower rate of ATP availability to the muscle. The sugar used in glycolysis can be provided by blood glucose or by metabolizing glycogen that is stored in the muscle. The breakdown of one glucose molecule produces two ATP and two molecules of pyruvic acid, which can be used in aerobic respiration or when oxygen levels are low, converted to lactic acid (Figure 10.12b).

If oxygen is available, pyruvic acid is used in aerobic respiration. However, if oxygen is not available, pyruvic acid is converted to lactic acid, which may contribute to muscle fatigue. This conversion allows the recycling of the enzyme NAD+ from NADH, which is needed for glycolysis to continue. This occurs during strenuous exercise when high amounts of energy are needed but oxygen cannot be sufficiently delivered to muscle. Glycolysis itself cannot be sustained for very long (approximately 1 minute of muscle activity), but it is useful in facilitating short bursts of high-intensity output. This is because glycolysis does not utilize glucose very efficiently, producing a net gain of two ATPs per molecule of glucose, and the end product of lactic acid, which may contribute to muscle fatigue as it accumulates.

Aerobic respiration is the breakdown of glucose or other nutrients in the presence of oxygen (O2) to produce carbon dioxide, water, and ATP. Approximately 95 percent of the ATP required for resting or moderately active muscles is provided by aerobic respiration, which takes place in mitochondria. The inputs for aerobic respiration include glucose circulating in the bloodstream, pyruvic acid, and fatty acids. Aerobic respiration is much more efficient than anaerobic glycolysis, producing approximately 36 ATPs per molecule of glucose versus four from glycolysis. However, aerobic respiration cannot be sustained without a steady supply of O2 to the skeletal muscle and is much slower (Figure 10.12c). To compensate, muscles store small amount of excess oxygen in proteins call myoglobin, allowing for more efficient muscle contractions and less fatigue. Aerobic training also increases the efficiency of the circulatory system so that O2 can be supplied to the muscles for longer periods of time.

Muscle fatigue occurs when a muscle can no longer contract in response to signals from the nervous system. The exact causes of muscle fatigue are not fully known, although certain factors have been correlated with the decreased muscle contraction that occurs during fatigue. ATP is needed for normal muscle contraction, and as ATP reserves are reduced, muscle function may decline. This may be more of a factor in brief, intense muscle output rather than sustained, lower intensity efforts. Lactic acid buildup may lower intracellular pH, affecting enzyme and protein activity. Imbalances in Na+ and K+ levels as a result of membrane depolarization may disrupt Ca++ flow out of the SR. Long periods of sustained exercise may damage the SR and the sarcolemma, resulting in impaired Ca++ regulation.

Intense muscle activity results in an oxygen debt, which is the amount of oxygen needed to compensate for ATP produced without oxygen during muscle contraction. Oxygen is required to restore ATP and creatine phosphate levels, convert lactic acid to pyruvic acid, and, in the liver, to convert lactic acid into glucose or glycogen. Other systems used during exercise also require oxygen, and all of these combined processes result in the increased breathing rate that occurs after exercise. Until the oxygen debt has been met, oxygen intake is elevated, even after exercise has stopped.

Relaxation of a Skeletal Muscle

Relaxing skeletal muscle fibers, and ultimately, the skeletal muscle, begins with the motor neuron, which stops releasing its chemical signal, ACh, into the synapse at the NMJ. The muscle fiber will repolarize, which closes the gates in the SR where Ca++ was being released. ATP-driven pumps will move Ca++ out of the sarcoplasm back into the SR. This results in the “reshielding” of the actin-binding sites on the thin filaments. Without the ability to form cross-bridges between the thin and thick filaments, the muscle fiber loses its tension and relaxes.

Muscle Strength

The number of skeletal muscle fibers in a given muscle is genetically determined and does not change. Muscle strength is directly related to the amount of myofibrils and sarcomeres within each fiber. Factors, such as hormones and stress (and artificial anabolic steroids), acting on the muscle can increase the production of sarcomeres and myofibrils within the muscle fibers, a change called hypertrophy, which results in the increased mass and bulk in a skeletal muscle. Likewise, decreased use of a skeletal muscle results in atrophy, where the number of sarcomeres and myofibrils disappear (but not the number of muscle fibers). It is common for a limb in a cast to show atrophied muscles when the cast is removed, and certain diseases, such as polio, show atrophied muscles.

Disorders of the…Muscular System

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a progressive weakening of the skeletal muscles. It is one of several diseases collectively referred to as “muscular dystrophy.” DMD is caused by a lack of the protein dystrophin, which helps the thin filaments of myofibrils bind to the sarcolemma. Without sufficient dystrophin, muscle contractions cause the sarcolemma to tear, causing an influx of Ca++, leading to cellular damage and muscle fiber degradation. Over time, as muscle damage accumulates, muscle mass is lost, and greater functional impairments develop.

DMD is an inherited disorder caused by an abnormal X chromosome. It primarily affects males, and it is usually diagnosed in early childhood. DMD usually first appears as difficulty with balance and motion, and then progresses to an inability to walk. It continues progressing upward in the body from the lower extremities to the upper body, where it affects the muscles responsible for breathing and circulation. It ultimately causes death due to respiratory failure, and those afflicted do not usually live past their 20s.

Because DMD is caused by a mutation in the gene that codes for dystrophin, it was thought that introducing healthy myoblasts into patients might be an effective treatment. Myoblasts are the embryonic cells responsible for muscle development, and ideally, they would carry healthy genes that could produce the dystrophin needed for normal muscle contraction. This approach has been largely unsuccessful in humans. A recent approach has involved attempting to boost the muscle’s production of utrophin, a protein similar to dystrophin that may be able to assume the role of dystrophin and prevent cellular damage from occurring.