Skeletal System

Figure 7.1 Child Looking at Bones Bone is a living tissue. Unlike the bones of a fossil made inert by a process of mineralization, a child’s bones will continue to grow and develop while contributing to the support and function of other body systems. (credit: James Emery)

Chapter Objectives

After studying this chapter, you will be able to:

- List and describe the functions of bones

- Describe the classes of bones

- Discuss the process of bone formation and development

- Explain how bone repairs itself after a fracture

- Discuss the effect of exercise, nutrition, and hormones on bone tissue

- Describe how an imbalance of calcium can affect bone tissue

Introduction

Bones make good fossils. While the soft tissue of a once living organism will decay and fall away over time, bone tissue will, under the right conditions, undergo a process of mineralization, effectively turning the bone to stone. A well-preserved fossil skeleton can give us a good sense of the size and shape of an organism, just as your skeleton helps to define your size and shape. Unlike a fossil skeleton, however, your skeleton is a structure of living tissue that grows, repairs, and renews itself. The bones within it are dynamic and complex organs that serve a number of important functions, including some necessary to maintain homeostasis.

Functions of the Skeletal System

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define bone, cartilage, and the skeletal system

- List and describe the functions of the skeletal system

Bone, or osseous tissue, is a hard, dense connective tissue that forms most of the adult skeleton, the support structure of the body. In the areas of the skeleton where bones move (for example, the ribcage and joints), cartilage, a semi-rigid form of connective tissue, provides flexibility and smooth surfaces for movement. The skeletal system is the body system composed of bones and cartilage and performs the following critical functions for the human body:

- supports the body

- facilitates movement

- protects internal organs

- produces blood cells

- stores and releases minerals and fat

Support, Movement, and Protection

The most apparent functions of the skeletal system are the gross functions—those visible by observation. Simply by looking at a person, you can see how the bones support, facilitate movement, and protect the human body.

Just as the steel beams of a building provide a scaffold to support its weight, the bones and cartilage of your skeletal system compose the scaffold that supports the rest of your body. Without the skeletal system, you would be a limp mass of organs, muscle, and skin.

Bones also facilitate movement by serving as points of attachment for your muscles. While some bones only serve as a support for the muscles, others also transmit the forces produced when your muscles contract. From a mechanical point of view, bones act as levers and joints serve as fulcrums (Figure 7.2). Unless a muscle spans a joint and contracts, a bone is not going to move. For information on the interaction of the skeletal and muscular systems, that is, the musculoskeletal system, seek additional content.

Figure 7.2 Bones Support Movement Bones act as levers when muscles span a joint and contract. (credit: Benjamin J. DeLong)

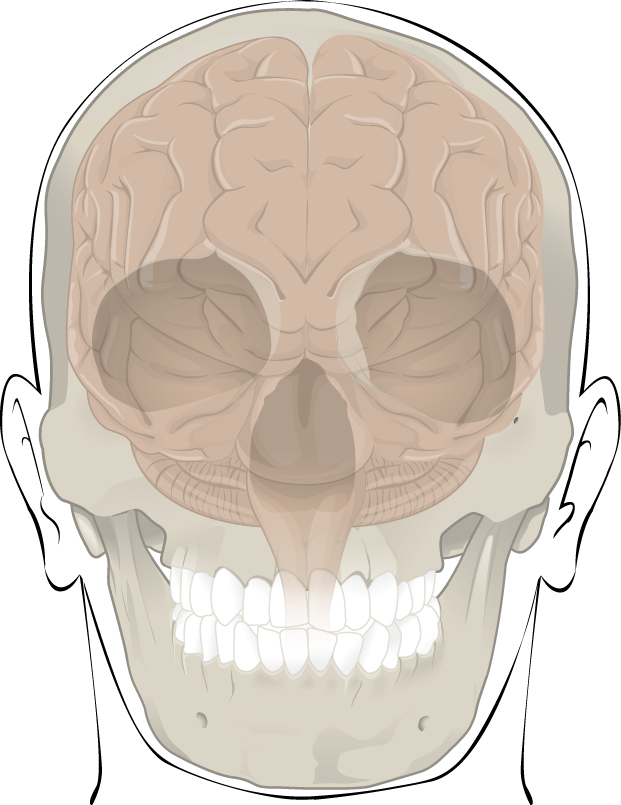

Bones also protect internal organs from injury by covering or surrounding them. For example, your ribs protect your lungs and heart, the bones of your vertebral column (spine) protect your spinal cord, and the bones of your cranium (skull) protect your brain (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Bones Protect Brain The cranium completely surrounds and protects the brain from non-traumatic injury.

Career Connection: Orthopedist

An orthopedist is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating disorders and injuries related to the musculoskeletal system. Some orthopedic problems can be treated with medications, exercises, braces, and other devices, but others may be best treated with surgery (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 Complex Brace An orthopedist will sometimes prescribe the use of a brace that reinforces the underlying bone structure it is being used to support. (credit: Becky Stern/Flickr)

While the origin of the word “orthopedics” (ortho- = “straight”; paed- = “child”), literally means “straightening of the child,” orthopedists can have patients who range from pediatric to geriatric. In recent years, orthopedists have even performed prenatal surgery to correct spina bifida, a congenital defect in which the neural canal in the spine of the fetus fails to close completely during embryologic development.

Orthopedists commonly treat bone and joint injuries but they also treat other bone conditions including curvature of the spine. Lateral curvatures (scoliosis) can be severe enough to slip under the shoulder blade (scapula) forcing it up as a hump. Spinal curvatures can also be excessive dorsoventrally (kyphosis) causing a hunch back and thoracic compression. These curvatures often appear in preteens as the result of poor posture, abnormal growth, or indeterminate causes. Mostly, they are readily treated by orthopedists. As people age, accumulated spinal column injuries and diseases like osteoporosis can also lead to curvatures of the spine, hence the stooping you sometimes see in the elderly.

Some orthopedists sub-specialize in sports medicine, which addresses both simple injuries, such as a sprained ankle, and complex injuries, such as a torn rotator cuff in the shoulder. Treatment can range from exercise to surgery.

Mineral Storage, Energy Storage, and Hematopoiesis

On a metabolic level, bone tissue performs several critical functions. For one, the bone matrix acts as a reservoir for a number of minerals important to the functioning of the body, especially calcium, and phosphorus. These minerals, incorporated into bone tissue, can be released back into the bloodstream to maintain levels needed to support physiological processes. Calcium ions, for example, are essential for muscle contractions and controlling the flow of other ions involved in the transmission of nerve impulses.

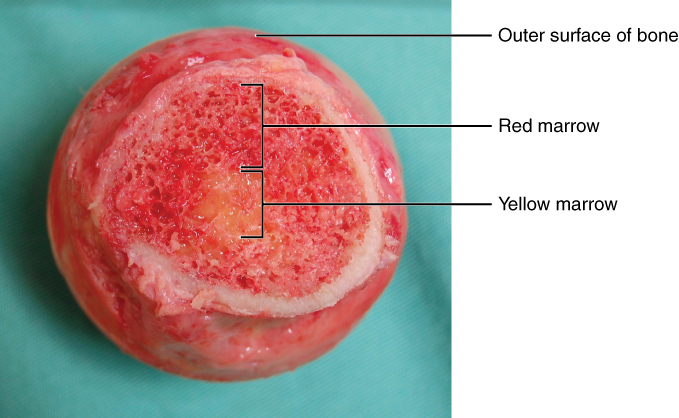

Bone also serves as a site for fat storage and blood cell production. The softer connective tissue that fills the interior of most bone is referred to as bone marrow (Figure 7.5). There are two types of bone marrow: yellow marrow and red marrow. Yellow marrow contains adipose tissue; the triglycerides stored in the adipocytes of the tissue can serve as a source of energy. Red marrow is where hematopoiesis—the production of blood cells—takes place. Red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets are all produced in the red marrow.

Figure 7.5 Head of Femur Showing Red and Yellow Marrow The head of the femur contains both yellow and red marrow. Yellow marrow stores fat. Red marrow is responsible for hematopoiesis. (credit: modification of work by “stevenfruitsmaak”/Wikimedia Commons)

Bone Classification

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Classify bones according to their shapes

- Describe the function of each category of bones

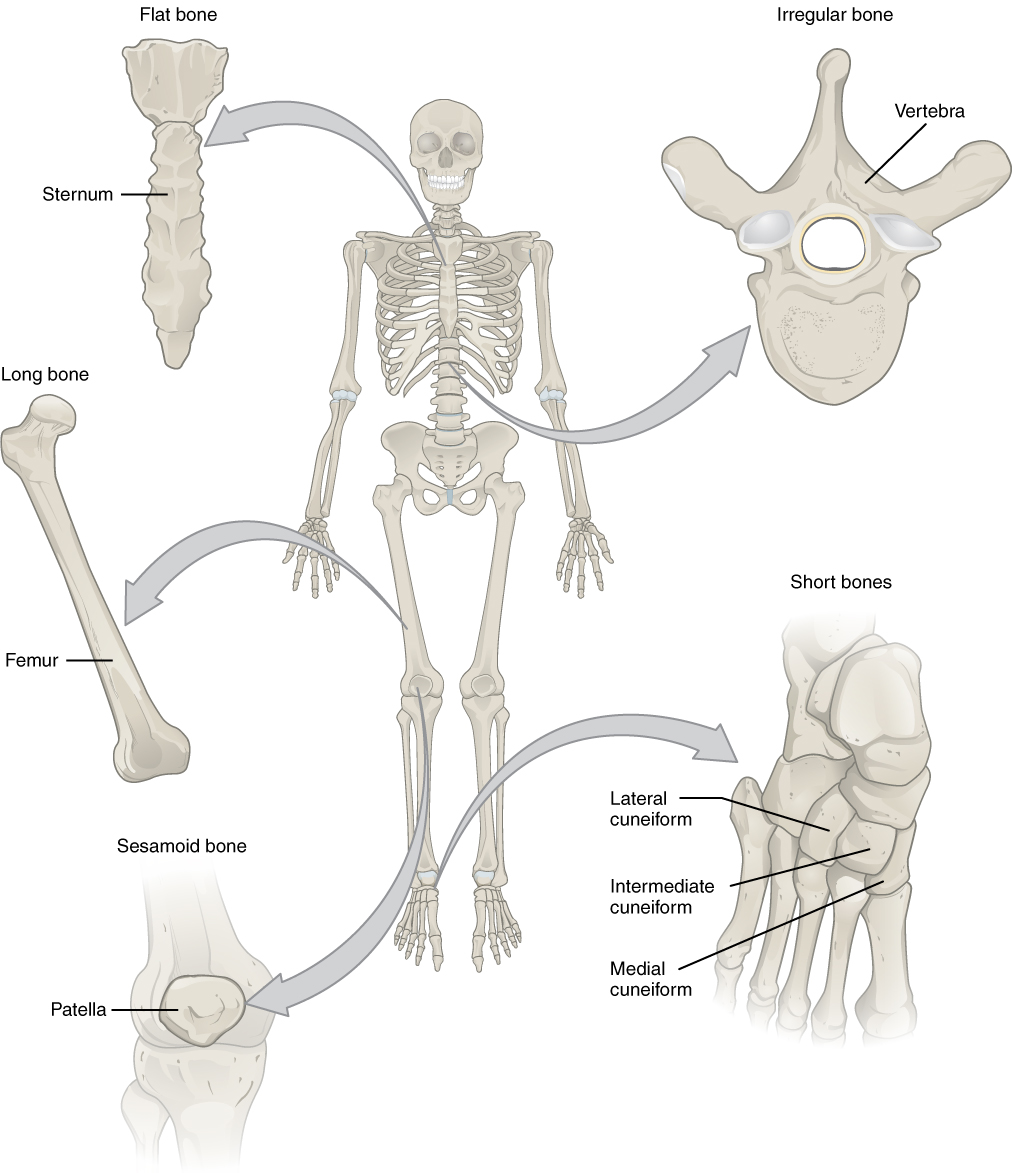

The 206 bones that compose the adult skeleton are divided into five categories based on their shapes (Figure 7.6). Their shapes and their functions are related such that each categorical shape of bone has a distinct function.

Figure 7.6 Classifications of Bones Bones are classified according to their shape.

Long Bones

A long bone is one that is cylindrical in shape, being longer than it is wide. Keep in mind, however, that the term describes the shape of a bone, not its size. Long bones are found in the arms (humerus, ulna, radius) and legs (femur, tibia, fibula), as well as in the fingers (metacarpals, phalanges) and toes (metatarsals, phalanges). Long bones function as levers; they move when muscles contract.

Short Bones

A short bone is one that is cube-like in shape, being approximately equal in length, width, and thickness. The only short bones in the human skeleton are in the carpals of the wrists and the tarsals of the ankles. Short bones provide stability and support as well as some limited motion.

Flat Bones

The term “flat bone” is somewhat of a misnomer because, although a flat bone is typically thin, it is also often curved. Examples include the cranial (skull) bones, the scapulae (shoulder blades), the sternum (breastbone), and the ribs. Flat bones serve as points of attachment for muscles and often protect internal organs.

Irregular Bones

An irregular bone is one that does not have any easily characterized shape and therefore does not fit any other classification. These bones tend to have more complex shapes, like the vertebrae that support the spinal cord and protect it from compressive forces. Many facial bones, particularly the ones containing sinuses, are classified as irregular bones.

Sesamoid Bones

A sesamoid bone is a small, round bone that, as the name suggests, is shaped like a sesame seed. These bones form in tendons (the sheaths of tissue that connect bones to muscles) where a great deal of pressure is generated in a joint. The sesamoid bones protect tendons by helping them overcome compressive forces. Sesamoid bones vary in number and placement from person to person but are typically found in tendons associated with the feet, hands, and knees. The patellae (singular = patella) are the only sesamoid bones found in common with every person. Table 7.1 reviews bone classifications with their associated features, functions, and examples.

Bone Classifications

|

Bone classification |

Features |

Function(s) |

Examples |

|

Long |

Cylinder-like shape, longer than it is wide |

Leverage |

Femur, tibia, fibula, metatarsals, humerus, ulna, radius, metacarpals, phalanges |

|

Short |

Cube-like shape, approximately equal in length, width, and thickness |

Provide stability, support, while allowing for some motion |

Carpals, tarsals |

|

Flat |

Thin and curved |

Points of attachment for muscles; protectors of internal organs |

Sternum, ribs, scapulae, cranial bones |

|

Irregular |

Complex shape |

Protect internal organs |

Vertebrae, facial bones |

|

Sesamoid |

Small and round; embedded in tendons |

Protect tendons from compressive forces |

Patellae |

Table 7.1

Bone Structure

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the anatomical features of a bone

- Define and list examples of bone markings

- Describe the histology of bone tissue

- Compare and contrast compact and spongy bone

- Identify the structures that compose compact and spongy bone

- Describe how bones are nourished and innervated

Bone tissue (osseous tissue) differs greatly from other tissues in the body. Bone is hard and many of its functions depend on that characteristic hardness. Later discussions in this chapter will show that bone is also dynamic in that its shape adjusts to accommodate stresses. This section will examine the gross anatomy of bone first and then move on to its histology.

Gross Anatomy of Bone

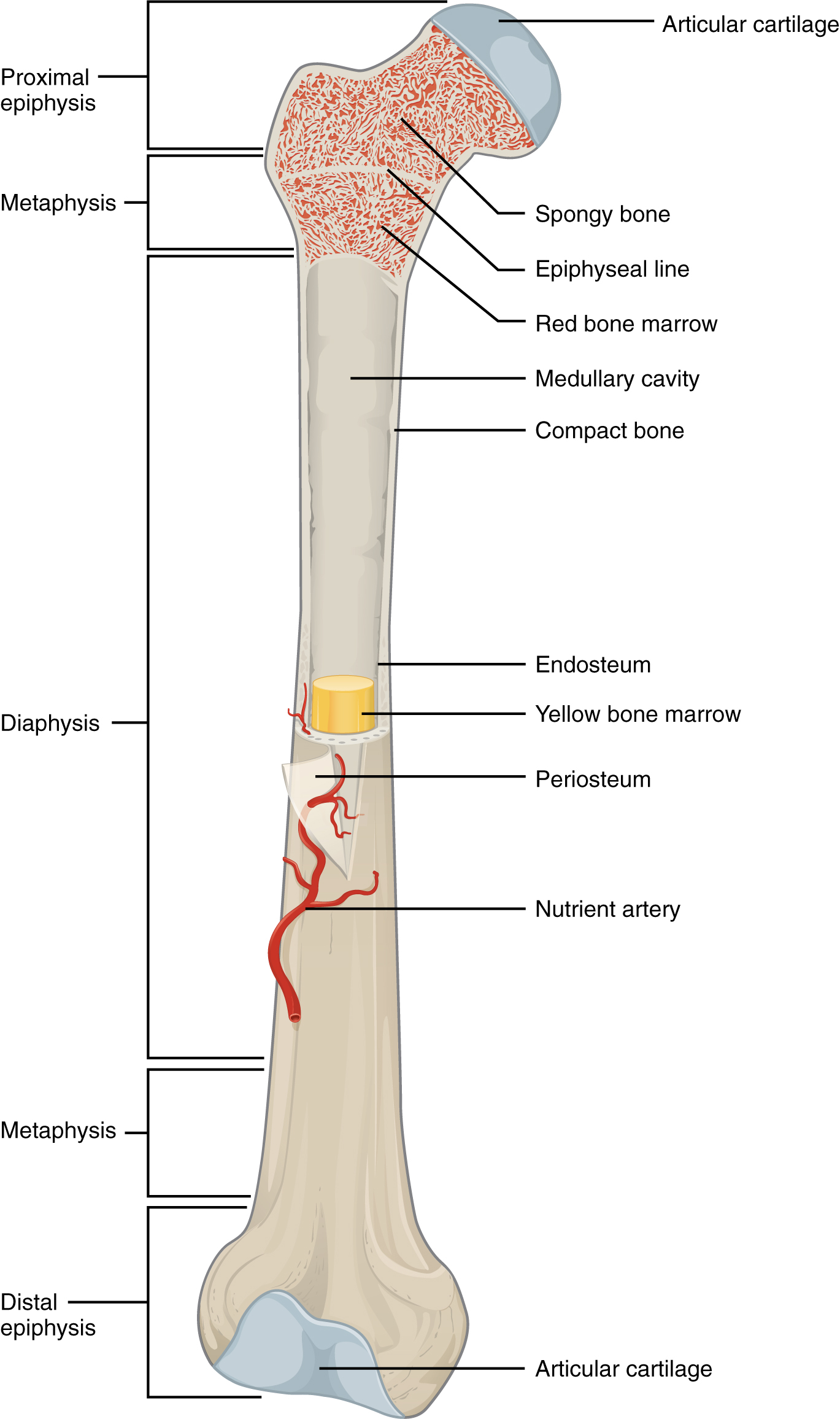

The structure of a long bone allows for the best visualization of all of the parts of a bone (Figure 7.7). A long bone has two parts: the diaphysis and the epiphysis. The diaphysis is the tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone. The hollow region in the diaphysis is called the medullary cavity, which is filled with yellow marrow. The walls of the diaphysis are composed of dense and hard compact bone.

Figure 7.7 Anatomy of a Long Bone A typical long bone shows the gross anatomical characteristics of bone.

The wider section at each end of the bone is called the epiphysis (plural = epiphyses), which is filled with spongy bone. Red marrow fills the spaces in the spongy bone. Each epiphysis meets the diaphysis at the metaphysis, the narrow area that contains the epiphyseal plate (growth plate), a layer of hyaline (transparent) cartilage in a growing bone. When the bone stops growing in early adulthood (approximately 18–21 years), the cartilage is replaced by osseous tissue and the epiphyseal plate becomes an epiphyseal line.

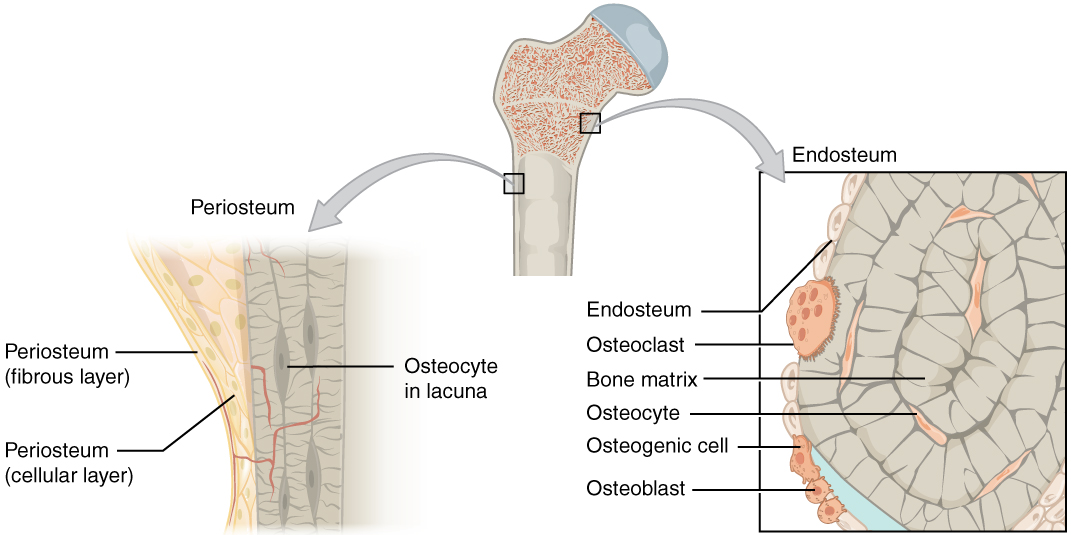

The medullary cavity has a delicate membranous lining called the endosteum (end- = “inside”; oste- = “bone”), where bone growth, repair, and remodeling occur. The outer surface of the bone is covered with a fibrous membrane called the periosteum (peri– = “around” or “surrounding”). The periosteum contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that nourish compact bone. Tendons and ligaments also attach to bones at the periosteum. The periosteum covers the entire outer surface except where the epiphyses meet other bones to form joints (Figure 7.8). In this region, the epiphyses are covered with articular cartilage, a thin layer of cartilage that reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber.

Figure 7.8 Periosteum and Endosteum The periosteum forms the outer surface of bone, and the endosteum lines the medullary cavity.

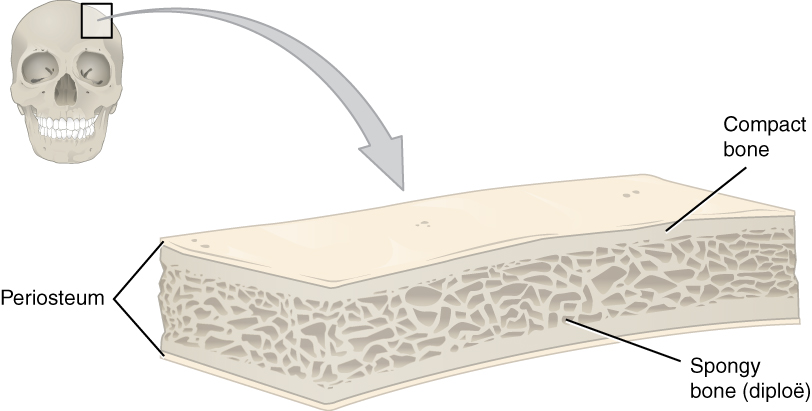

Flat bones, like those of the cranium, consist of a layer of spongy bone, lined on either side by a layer of compact bone (Figure 7.9). The two layers of compact bone and the interior spongy bone work together to protect the internal organs. If the outer layer of a cranial bone fractures, the brain is still protected by the intact inner layer.

Figure 7.9 Anatomy of a Flat Bone This cross-section of a flat bone shows the spongy bone lined on either side by a layer of compact bone.

Bone Markings

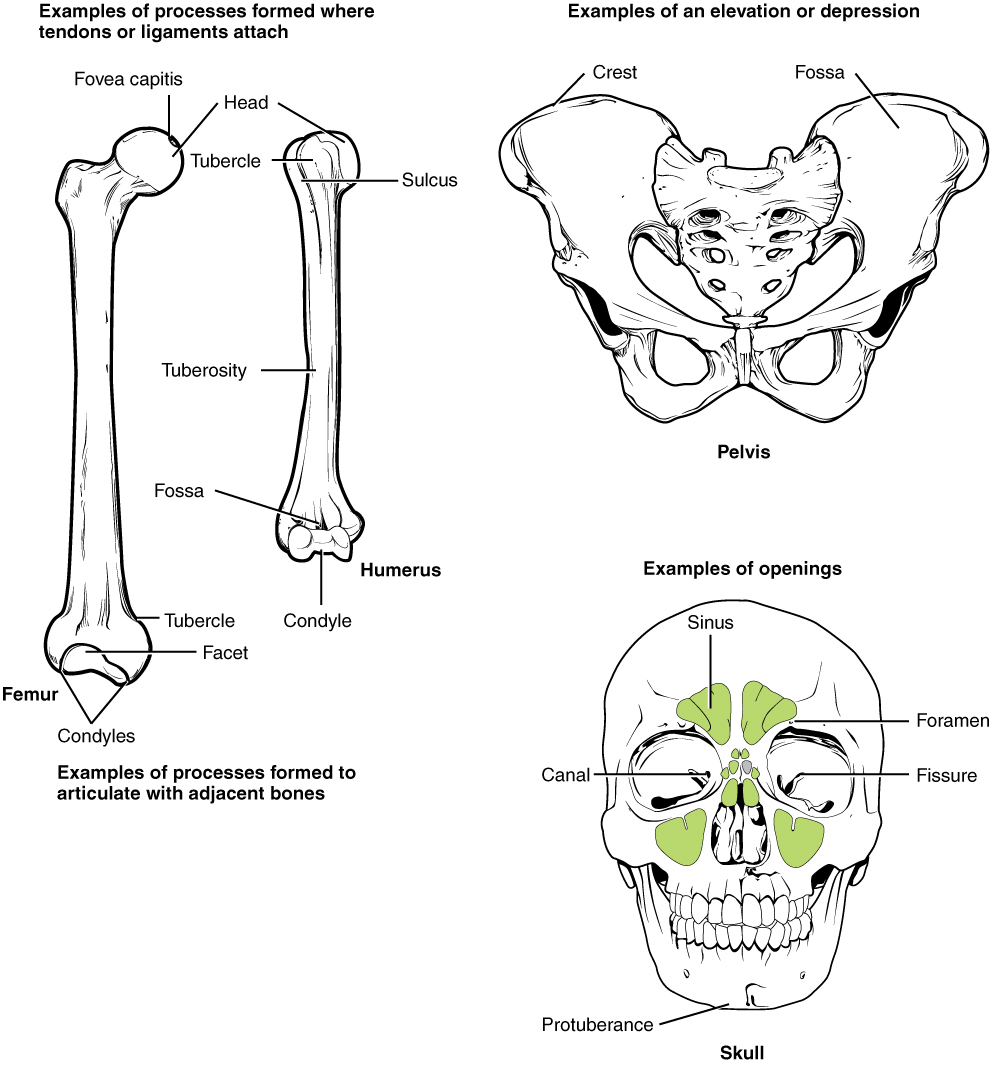

The surface features of bones vary considerably, depending on the function and location in the body. Table 7.2 describes the bone markings, which are illustrated in (Figure 7.10). There are three general classes of bone markings: (1) articulations, (2) projections, and (3) holes. As the name implies, an articulation is where two bone surfaces come together (articulus = “joint”). These surfaces tend to conform to one another, such as one being rounded and the other cupped, to facilitate the function of the articulation. A projection is an area of a bone that projects above the surface of the bone. These are the attachment points for tendons and ligaments. In general, their size and shape is an indication of the forces exerted through the attachment to the bone. A hole is an opening or groove in the bone that allows blood vessels and nerves to enter the bone. As with the other markings, their size and shape reflect the size of the vessels and nerves that penetrate the bone at these points.

Bone Markings

|

Marking |

Description |

Example |

|

Articulations |

Where two bones meet |

Knee joint |

|

Head |

Prominent rounded surface |

Head of femur |

|

Facet |

Flat surface |

Vertebrae |

|

Condyle |

Rounded surface |

Occipital condyles |

|

Projections |

Raised markings |

Spinous process of the vertebrae |

|

Protuberance |

Protruding |

Chin |

|

Process |

Prominence feature |

Transverse process of vertebra |

|

Spine |

Sharp process |

Ischial spine |

|

Tubercle |

Small, rounded process |

Tubercle of humerus |

|

Tuberosity |

Rough surface |

Deltoid tuberosity |

|

Line |

Slight, elongated ridge |

Temporal lines of the parietal bones |

|

Crest |

Ridge |

Iliac crest |

|

Holes |

Holes and depressions |

Foramen (holes through which blood vessels can pass through) |

|

Fossa |

Elongated basin |

Mandibular fossa |

|

Fovea |

Small pit |

Fovea capitis on the head of the femur |

|

Sulcus |

Groove |

Sigmoid sulcus of the temporal bones |

|

Canal |

Passage in bone |

Auditory canal |

|

Fissure |

Slit through bone |

Auricular fissure |

|

Foramen |

Hole through bone |

Foramen magnum in the occipital bone |

|

Meatus |

Opening into canal |

External auditory meatus |

|

Sinus |

Air-filled space in bone |

Nasal sinus |

Table 7.2

Figure 7.10 Bone Features The surface features of bones depend on their function, location, attachment of ligaments and tendons, or the penetration of blood vessels and nerves.

Bone Cells and Tissue

Bone contains a relatively small number of cells entrenched in a matrix of collagen fibers that provide a surface for inorganic salt crystals to adhere. These salt crystals form when calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate combine to create hydroxyapatite, which incorporates other inorganic salts like magnesium hydroxide, fluoride, and sulfate as it crystallizes, or calcifies, on the collagen fibers. The hydroxyapatite crystals give bones their hardness and strength, while the collagen fibers give them flexibility so that they are not brittle.

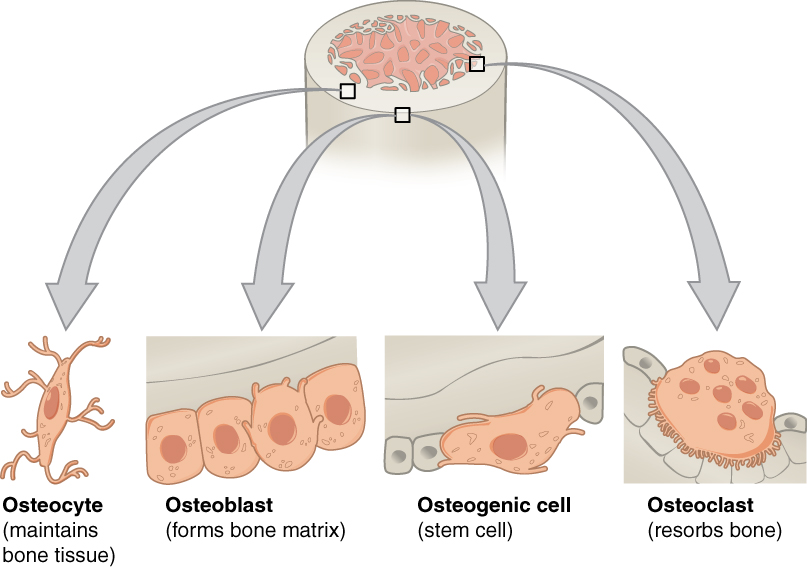

Although bone cells compose a small amount of the bone volume, they are crucial to the function of bones. Four types of cells are found within bone tissue: osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteogenic cells, and osteoclasts (Figure 7.11).

Figure 7.11 Bone Cells Four types of cells are found within bone tissue. Osteogenic cells are undifferentiated and develop into osteoblasts. When osteoblasts get trapped within the calcified matrix, their structure and function changes, and they become osteocytes. Osteoclasts develop from monocytes and macrophages and differ in appearance from other bone cells.

The osteoblast is the bone cell responsible for forming new bone and is found in the growing portions of bone, including the periosteum and endosteum. Osteoblasts, which do not divide, synthesize and secrete the collagen matrix and calcium salts. As the secreted matrix surrounding the osteoblast calcifies, the osteoblast become trapped within it; as a result, it changes in structure and becomes an osteocyte, the primary cell of mature bone and the most common type of bone cell. Each osteocyte is located in a space called a lacuna and is surrounded by bone tissue. Osteocytes maintain the mineral concentration of the matrix via the secretion of enzymes. Like osteoblasts, osteocytes lack mitotic activity. They can communicate with each other and receive nutrients via long cytoplasmic processes that extend through canaliculi (singular = canaliculus), channels within the bone matrix.

If osteoblasts and osteocytes are incapable of mitosis, then how are they replenished when old ones die? The answer lies in the properties of a third category of bone cells—the osteogenic cell. These osteogenic cells are undifferentiated with high mitotic activity and they are the only bone cells that divide. Immature osteogenic cells are found in the deep layers of the periosteum and the marrow. They differentiate and develop into osteoblasts.

The dynamic nature of bone means that new tissue is constantly formed, and old, injured, or unnecessary bone is dissolved for repair or for calcium release. The cell responsible for bone resorption, or breakdown, is the osteoclast. They are found on bone surfaces, are multinucleated, and originate from monocytes and macrophages, two types of white blood cells, not from osteogenic cells. Osteoclasts are continually breaking down old bone while osteoblasts are continually forming new bone. The ongoing balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts is responsible for the constant but subtle reshaping of bone. Table 7.3 reviews the bone cells, their functions, and locations.

Bone Cells

|

Cell type |

Function |

Location |

|

Osteogenic cells |

Develop into osteoblasts |

Deep layers of the periosteum and the marrow |

|

Osteoblasts |

Bone formation |

Growing portions of bone, including periosteum and endosteum |

|

Osteocytes |

Maintain mineral concentration of matrix |

Entrapped in matrix |

|

Osteoclasts |

Bone resorption |

Bone surfaces and at sites of old, injured, or unneeded bone |

Table 7.3

Compact and Spongy Bone

The differences between compact and spongy bone are best explored via their histology. Most bones contain compact and spongy osseous tissue, but their distribution and concentration vary based on the bone’s overall function. Compact bone is dense so that it can withstand compressive forces, while spongy (cancellous) bone has open spaces and supports shifts in weight distribution.

Compact Bone

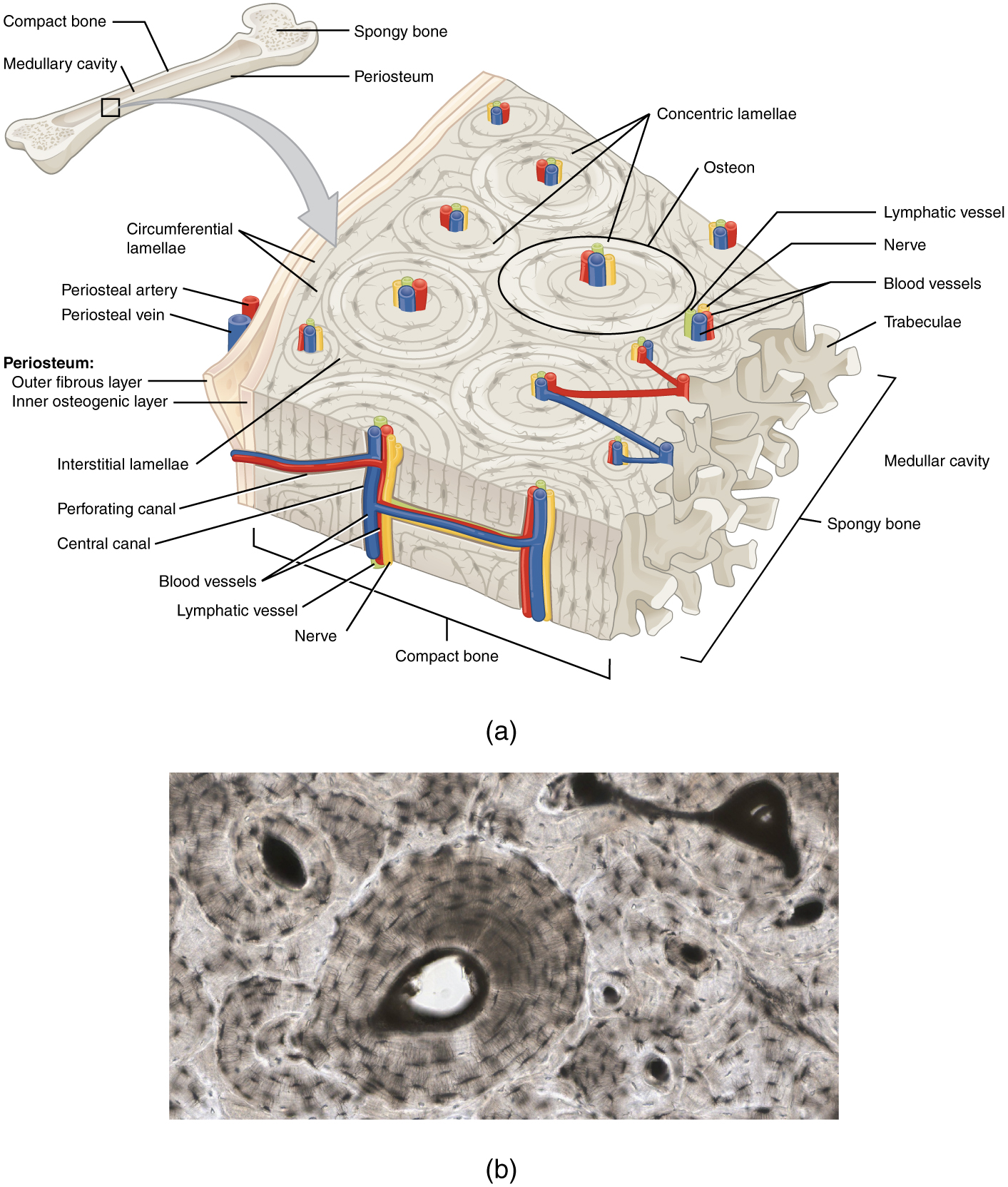

Compact bone is the denser, stronger of the two types of bone tissue (Figure 7.12). It can be found under the periosteum and in the diaphyses of long bones, where it provides support and protection.

Figure 7.12 Diagram of Compact Bone (a) This cross-sectional view of compact bone shows the basic structural unit, the osteon. (b) In this micrograph of the osteon, you can clearly see the concentric lamellae and central canals. LM × 40. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

The microscopic structural unit of compact bone is called an osteon, or Haversian system. Each osteon is composed of concentric rings of calcified matrix called lamellae (singular = lamella). Running down the center of each osteon is the central canal, or Haversian canal, which contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels. These vessels and nerves branch off at right angles through a perforating canal, also known as Volkmann’s canals, to extend to the periosteum and endosteum.

The osteocytes are located inside spaces called lacunae (singular = lacuna), found at the borders of adjacent lamellae. As described earlier, canaliculi connect with the canaliculi of other lacunae and eventually with the central canal. This system allows nutrients to be transported to the osteocytes and wastes to be removed from them.

Spongy (Cancellous) Bone

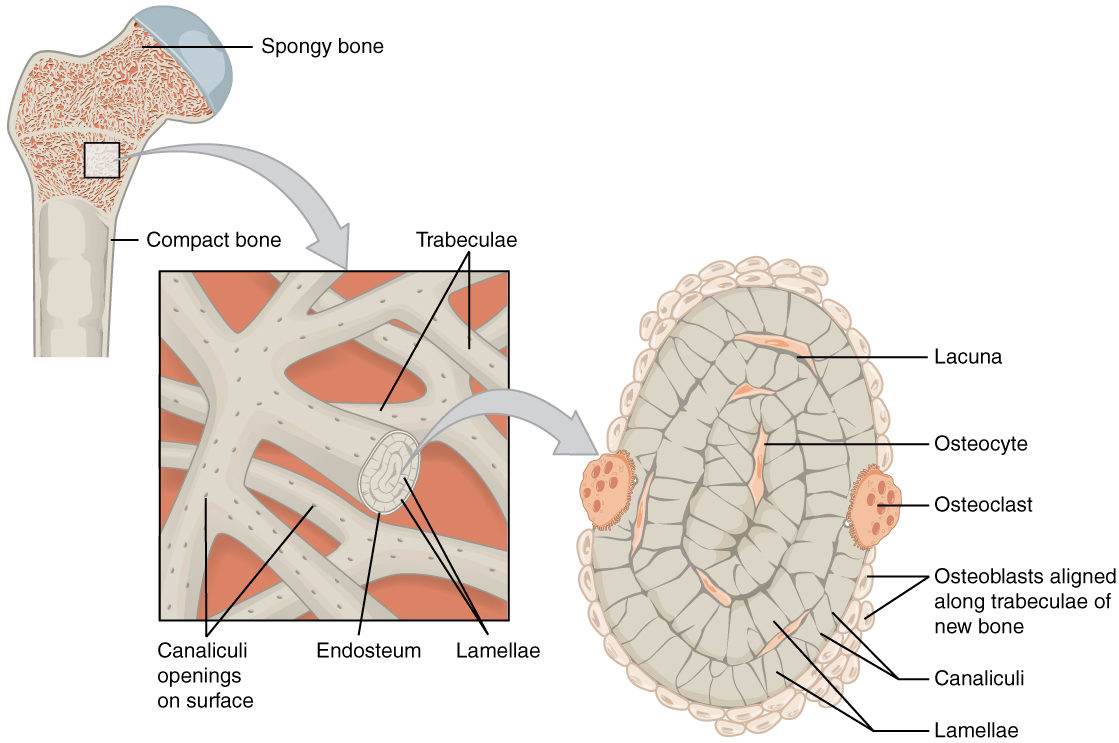

Like compact bone, spongy bone, also known as cancellous bone, contains osteocytes housed in lacunae, but they are not arranged in concentric circles. Instead, the lacunae and osteocytes are found in a lattice-like network of matrix spikes called trabeculae (singular = trabecula) (Figure 7.13). The trabeculae may appear to be a random network, but each trabecula forms along lines of stress to provide strength to the bone. The spaces of the trabeculated network provide balance to the dense and heavy compact bone by making bones lighter so that muscles can move them more easily. In addition, the spaces in some spongy bones contain red marrow, protected by the trabeculae, where hematopoiesis occurs.

Figure 7.13 Diagram of Spongy Bone Spongy bone is composed of trabeculae that contain the osteocytes. Red marrow fills the spaces in some bones.

Aging and the…Skeletal System: Paget’s Disease

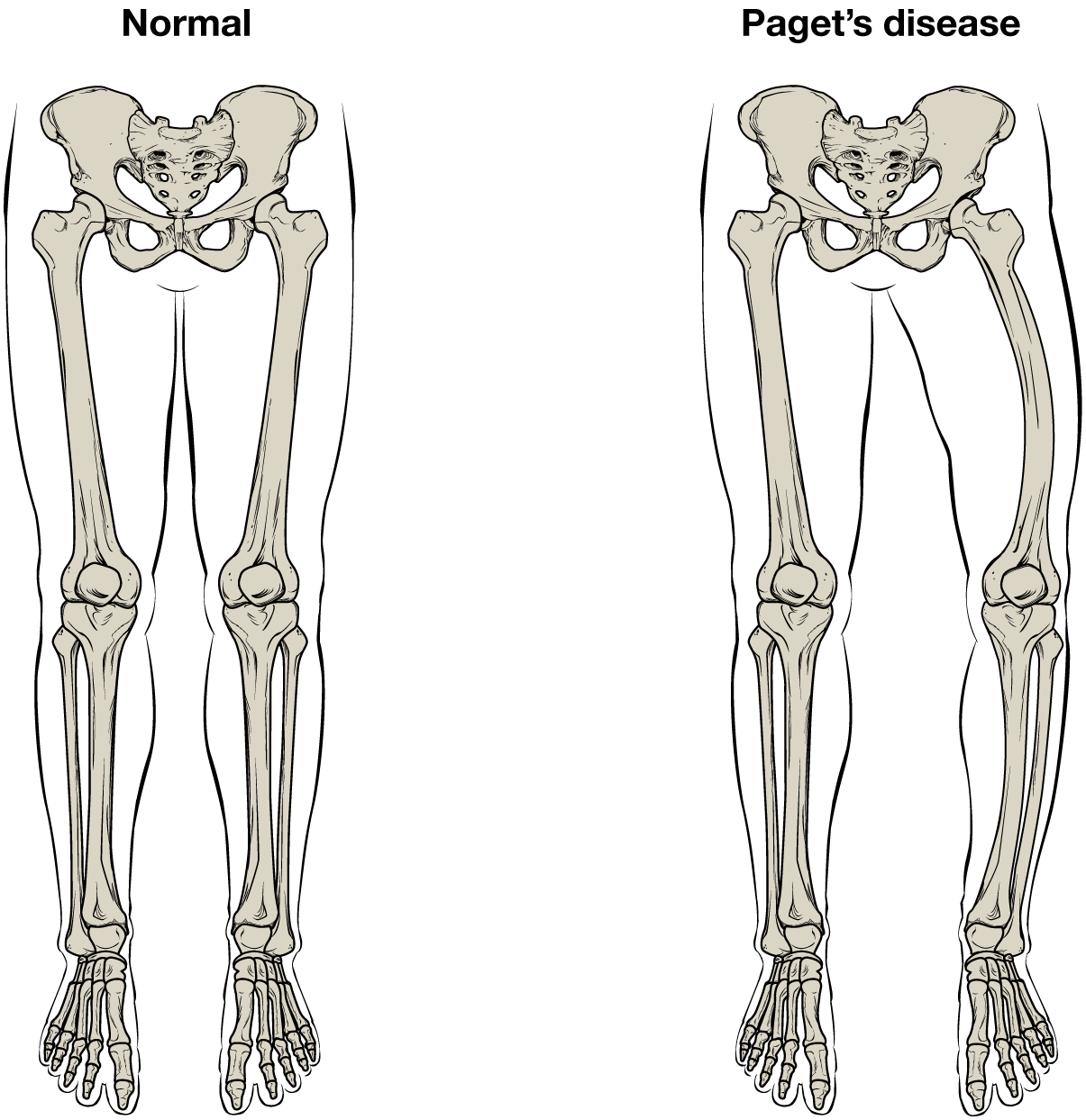

Paget’s disease usually occurs in adults over age 40. It is a disorder of the bone remodeling process that begins with overactive osteoclasts. This means more bone is resorbed than is laid down. The osteoblasts try to compensate but the new bone they lay down is weak and brittle and therefore prone to fracture.

While some people with Paget’s disease have no symptoms, others experience pain, bone fractures, and bone deformities (Figure 7.14). Bones of the pelvis, skull, spine, and legs are the most commonly affected. When occurring in the skull, Paget’s disease can cause headaches and hearing loss.

Figure 7.14 Paget’s Disease Normal leg bones are relatively straight, but those affected by Paget’s disease are porous and curved.

What causes the osteoclasts to become overactive? The answer is still unknown, but hereditary factors seem to play a role. Some scientists believe Paget’s disease is due to an as-yet-unidentified virus.

Paget’s disease is diagnosed via imaging studies and lab tests. X-rays may show bone deformities or areas of bone resorption. Bone scans are also useful. In these studies, a dye containing a radioactive ion is injected into the body. Areas of bone resorption have an affinity for the ion, so they will light up on the scan if the ions are absorbed. In addition, blood levels of an enzyme called alkaline phosphatase are typically elevated in people with Paget’s disease.

Bisphosphonates, drugs that decrease the activity of osteoclasts, are often used in the treatment of Paget’s disease. However, in a small percentage of cases, bisphosphonates themselves have been linked to an increased risk of fractures because the old bone that is left after bisphosphonates are administered becomes worn out and brittle. Still, most doctors feel that the benefits of bisphosphonates more than outweigh the risk; the medical professional has to weigh the benefits and risks on a case-by-case basis. Bisphosphonate treatment can reduce the overall risk of deformities or fractures, which in turn reduces the risk of surgical repair and its associated risks and complications.

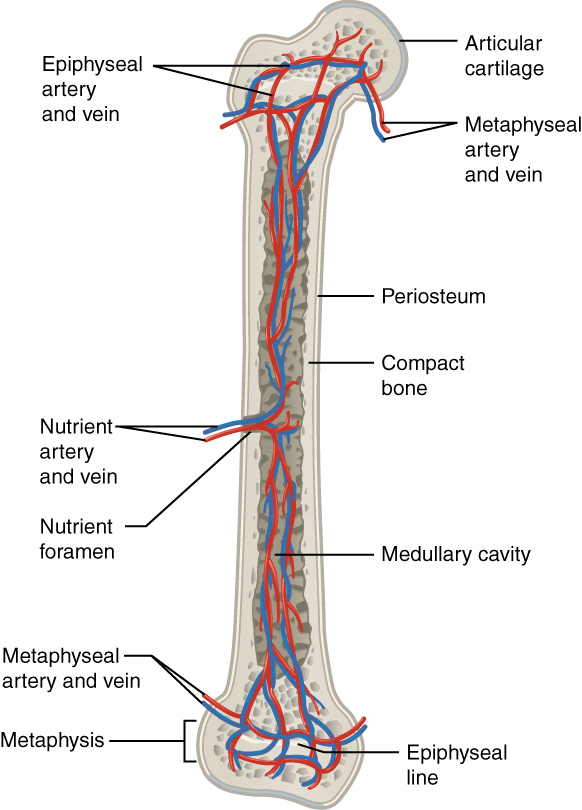

Blood and Nerve Supply

The spongy bone and medullary cavity receive nourishment from arteries that pass through the compact bone. The arteries enter through the nutrient foramen (plural = foramina), small openings in the diaphysis (Figure 7.15). The osteocytes in spongy bone are nourished by blood vessels of the periosteum that penetrate spongy bone and blood that circulates in the marrow cavities. As the blood passes through the marrow cavities, it is collected by veins, which then pass out of the bone through the foramina.

In addition to the blood vessels, nerves follow the same paths into the bone where they tend to concentrate in the more metabolically active regions of the bone. The nerves sense pain, and it appears the nerves also play roles in regulating blood supplies and in bone growth, hence their concentrations in metabolically active sites of the bone.

Figure 7.15 Diagram of Blood and Nerve Supply to Bone Blood vessels and nerves enter the bone through the nutrient foramen.

Interactive Link

Watch this video to see the microscopic features of a bone.

Bone Formation and Development

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the function of cartilage

- List the steps of intramembranous ossification

- List the steps of endochondral ossification

- Explain the growth activity at the epiphyseal plate

- Compare and contrast the processes of modeling and remodeling

In the early stages of embryonic development, the embryo’s skeleton consists of fibrous membranes and hyaline cartilage. By the sixth or seventh week of embryonic life, the actual process of bone development, ossification (osteogenesis), begins. There are two osteogenic pathways—intramembranous ossification and endochondral ossification—but bone is the same regardless of the pathway that produces it.

Cartilage Templates

Bone is a replacement tissue; that is, it uses a model tissue on which to lay down its mineral matrix. For skeletal development, the most common template is cartilage. During fetal development, a framework is laid down that determines where bones will form. This framework is a flexible, semi-solid matrix produced by chondroblasts and consists of hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate, collagen fibers, and water. As the matrix surrounds and isolates chondroblasts, they are called chondrocytes. Unlike most connective tissues, cartilage is avascular, meaning that it has no blood vessels supplying nutrients and removing metabolic wastes. All of these functions are carried on by diffusion through the matrix. This is why damaged cartilage does not repair itself as readily as most tissues do.

Throughout fetal development and into childhood growth and development, bone forms on the cartilaginous matrix. By the time a fetus is born, most of the cartilage has been replaced with bone. Some additional cartilage will be replaced throughout childhood, and some cartilage remains in the adult skeleton.

Intramembranous Ossification

During intramembranous ossification, compact and spongy bone develops directly from sheets of mesenchymal (undifferentiated) connective tissue. The flat bones of the face, most of the cranial bones, and the clavicles (collarbones) are formed via intramembranous ossification.

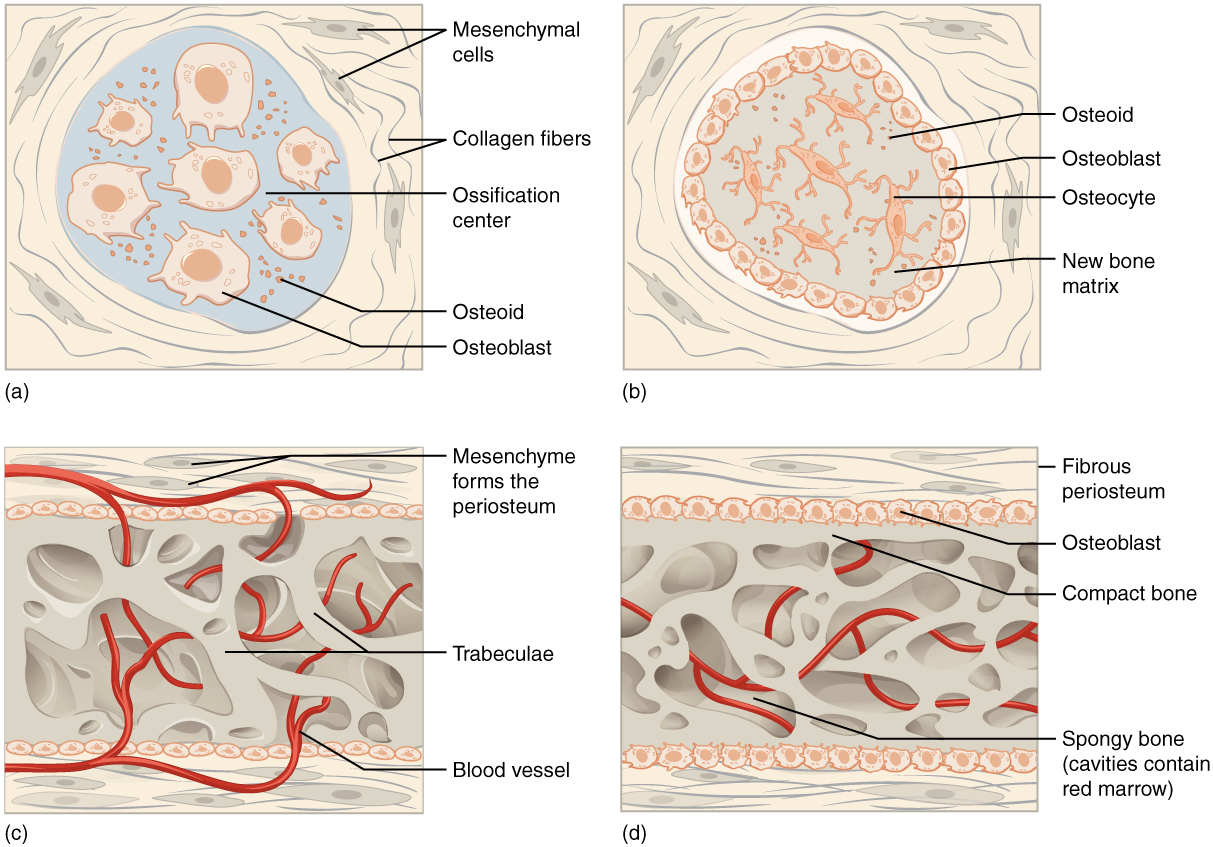

The process begins when mesenchymal cells in the embryonic skeleton gather together and begin to differentiate into specialized cells (Figure 7.16a). Some of these cells will differentiate into capillaries, while others will become osteogenic cells and then osteoblasts. Although they will ultimately be spread out by the formation of bone tissue, early osteoblasts appear in a cluster called an ossification center.

The osteoblasts secrete osteoid, uncalcified matrix, which calcifies (hardens) within a few days as mineral salts are deposited on it, thereby entrapping the osteoblasts within. Once entrapped, the osteoblasts become osteocytes (Figure 7.16b). As osteoblasts transform into osteocytes, osteogenic cells in the surrounding connective tissue differentiate into new osteoblasts.

Osteoid (unmineralized bone matrix) secreted around the capillaries results in a trabecular matrix, while osteoblasts on the surface of the spongy bone become the periosteum (Figure 7.16c). The periosteum then creates a protective layer of compact bone superficial to the trabecular bone. The trabecular bone crowds nearby blood vessels, which eventually condense into red marrow (Figure 7.16d).

Figure 7.16 Intramembranous Ossification Intramembranous ossification follows four steps. (a) Mesenchymal cells group into clusters, and ossification centers form. (b) Secreted osteoid traps osteoblasts, which then become osteocytes. (c) Trabecular matrix and periosteum form. (d) Compact bone develops superficial to the trabecular bone, and crowded blood vessels condense into red marrow.

Intramembranous ossification begins in utero during fetal development and continues on into adolescence. At birth, the skull and clavicles are not fully ossified nor are the sutures of the skull closed. This allows the skull and shoulders to deform during passage through the birth canal. The last bones to ossify via intramembranous ossification are the flat bones of the face, which reach their adult size at the end of the adolescent growth spurt.

Endochondral Ossification

In endochondral ossification, bone develops by replacing hyaline cartilage. Cartilage does not become bone. Instead, cartilage serves as a template to be completely replaced by new bone. Endochondral ossification takes much longer than intramembranous ossification. Bones at the base of the skull and long bones form via endochondral ossification.

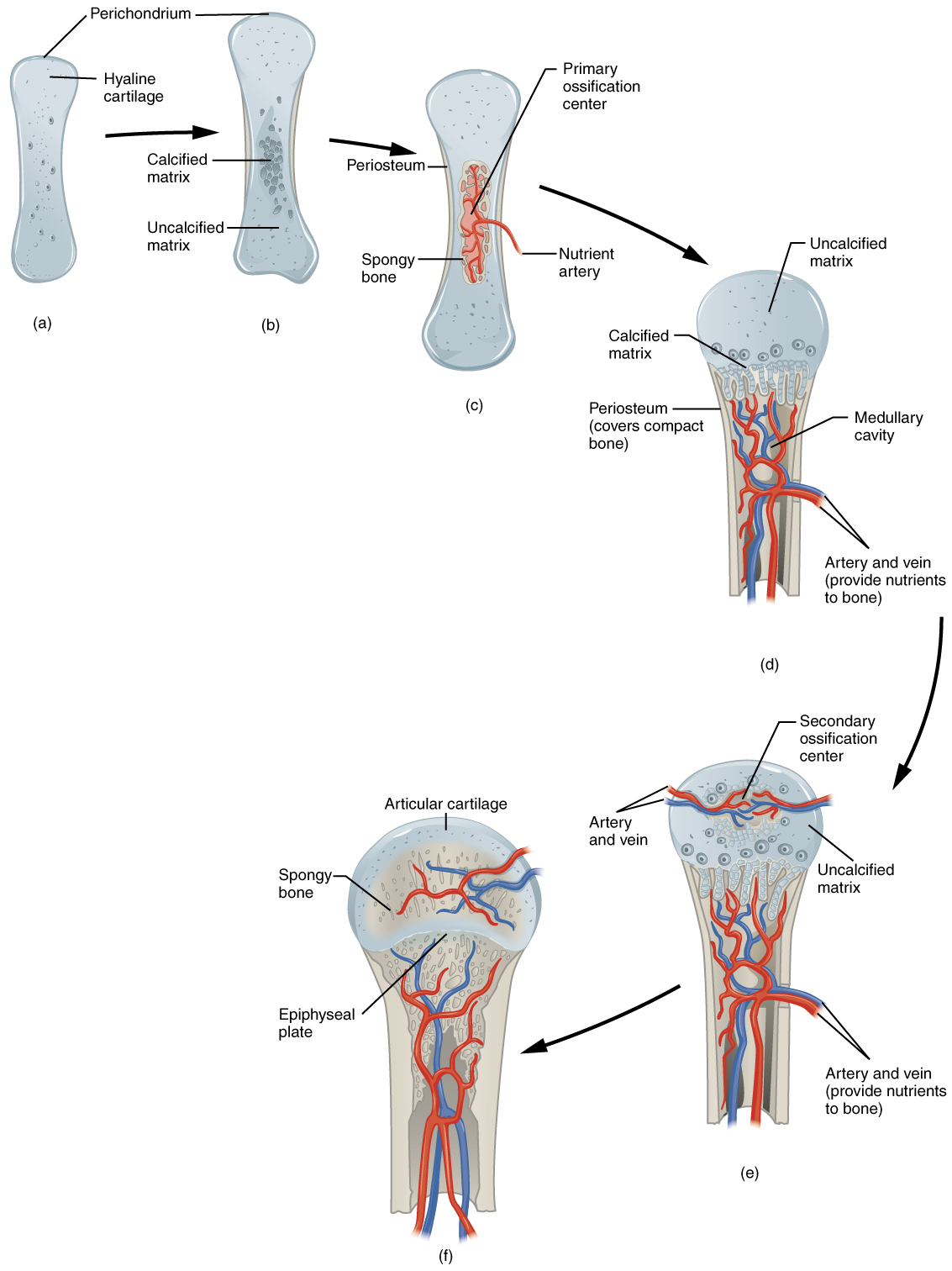

In a long bone, for example, at about 6 to 8 weeks after conception, some of the mesenchymal cells differentiate into chondrocytes (cartilage cells) that form the cartilaginous skeletal precursor of the bones (Figure 7.17a). Soon after, the perichondrium, a membrane that covers the cartilage, appears Figure 7.17b).

Figure 7.17 Endochondral Ossification Endochondral ossification follows five steps. (a) Mesenchymal cells differentiate into chondrocytes. (b) The cartilage model of the future bony skeleton and the perichondrium form. (c) Capillaries penetrate cartilage. Perichondrium transforms into periosteum. Periosteal collar develops. Primary ossification center develops. (d) Cartilage and chondrocytes continue to grow at ends of the bone. (e) Secondary ossification centers develop. (f) Cartilage remains at epiphyseal (growth) plate and at joint surface as articular cartilage.

As more matrix is produced, the chondrocytes in the center of the cartilaginous model grow in size. As the matrix calcifies, nutrients can no longer reach the chondrocytes. This results in their death and the disintegration of the surrounding cartilage. Blood vessels invade the resulting spaces, not only enlarging the cavities but also carrying osteogenic cells with them, many of which will become osteoblasts. These enlarging spaces eventually combine to become the medullary cavity.

As the cartilage grows, capillaries penetrate it. This penetration initiates the transformation of the perichondrium into the bone-producing periosteum. Here, the osteoblasts form a periosteal collar of compact bone around the cartilage of the diaphysis. By the second or third month of fetal life, bone cell development and ossification ramps up and creates the primary ossification center, a region deep in the periosteal collar where ossification begins (Figure 7.17c).

While these deep changes are occurring, chondrocytes and cartilage continue to grow at the ends of the bone (the future epiphyses), which increases the bone’s length at the same time bone is replacing cartilage in the diaphyses. By the time the fetal skeleton is fully formed, cartilage only remains at the joint surface as articular cartilage and between the diaphysis and epiphysis as the epiphyseal plate, the latter of which is responsible for the longitudinal growth of bones. After birth, this same sequence of events (matrix mineralization, death of chondrocytes, invasion of blood vessels from the periosteum, and seeding with osteogenic cells that become osteoblasts) occurs in the epiphyseal regions, and each of these centers of activity is referred to as a secondary ossification center (Figure 7.17e).

How Bones Grow in Length

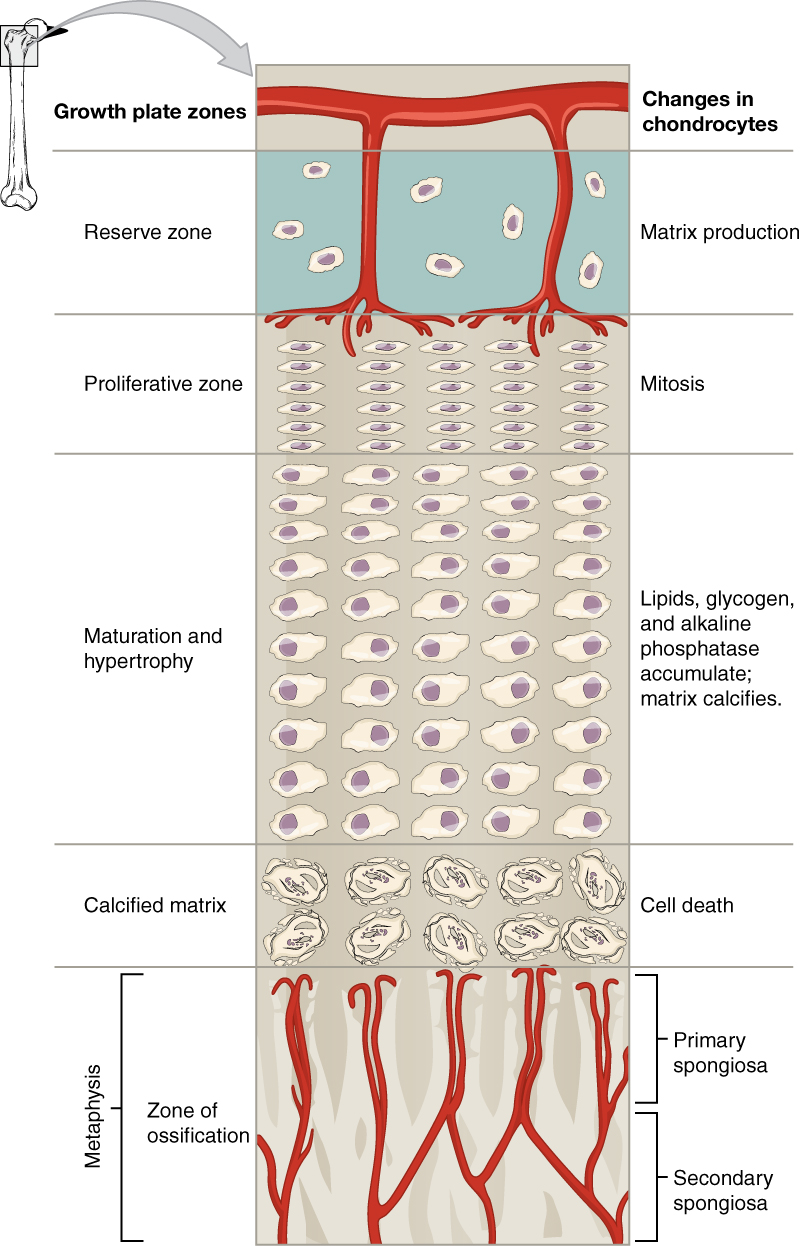

The epiphyseal plate is the area of growth in a long bone. It is a layer of hyaline cartilage where ossification occurs in immature bones. On the epiphyseal side of the epiphyseal plate, cartilage is formed. On the diaphyseal side, cartilage is ossified, and the diaphysis grows in length. The epiphyseal plate is composed of four zones of cells and activity (Figure 7.18). The reserve zone is the region closest to the epiphyseal end of the plate and contains small chondrocytes within the matrix. These chondrocytes do not participate in bone growth but secure the epiphyseal plate to the osseous tissue of the epiphysis.

Figure 7.18 Longitudinal Bone Growth The epiphyseal plate is responsible for longitudinal bone growth.

The proliferative zone is the next layer toward the diaphysis and contains stacks of slightly larger chondrocytes. It makes new chondrocytes (via mitosis) to replace those that die at the diaphyseal end of the plate. Chondrocytes in the next layer, the zone of maturation and hypertrophy, are older and larger than those in the proliferative zone. The more mature cells are situated closer to the diaphyseal end of the plate. The longitudinal growth of bone is a result of cellular division in the proliferative zone and the maturation of cells in the zone of maturation and hypertrophy.

Most of the chondrocytes in the zone of calcified matrix, the zone closest to the diaphysis, are dead because the matrix around them has calcified. Capillaries and osteoblasts from the diaphysis penetrate this zone, and the osteoblasts secrete bone tissue on the remaining calcified cartilage. Thus, the zone of calcified matrix connects the epiphyseal plate to the diaphysis. A bone grows in length when osseous tissue is added to the diaphysis.

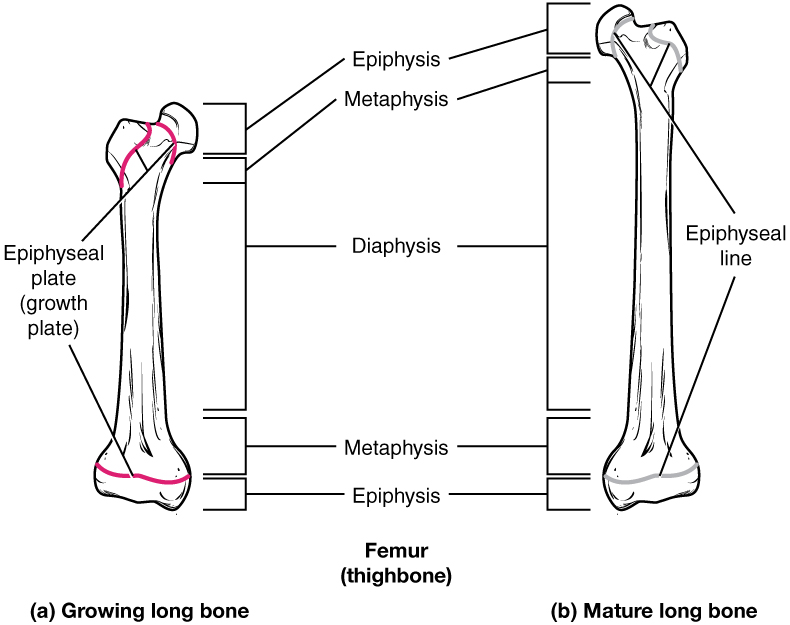

Bones continue to grow in length until early adulthood. The rate of growth is controlled by hormones, which will be discussed later. When the chondrocytes in the epiphyseal plate cease their proliferation and bone replaces the cartilage, longitudinal growth stops. All that remains of the epiphyseal plate is the epiphyseal line (Figure 7.19).

Figure 7.19 Progression from Epiphyseal Plate to Epiphyseal Line As a bone matures, the epiphyseal plate progresses to an epiphyseal line. (a) Epiphyseal plates are visible in a growing bone. (b) Epiphyseal lines are the remnants of epiphyseal plates in a mature bone.

How Bones Grow in Diameter

While bones are increasing in length, they are also increasing in diameter; growth in diameter can continue even after longitudinal growth ceases. This is called appositional growth. Osteoclasts resorb old bone that lines the medullary cavity, while osteoblasts, via intramembranous ossification, produce new bone tissue beneath the periosteum. The erosion of old bone along the medullary cavity and the deposition of new bone beneath the periosteum not only increase the diameter of the diaphysis but also increase the diameter of the medullary cavity. This process is called modeling.

Bone Remodeling

The process in which matrix is resorbed on one surface of a bone and deposited on another is known as bone modeling. Modeling primarily takes place during a bone’s growth. However, in adult life, bone undergoes remodeling, in which resorption of old or damaged bone takes place on the same surface where osteoblasts lay new bone to replace that which is resorbed. Injury, exercise, and other activities lead to remodeling. Those influences are discussed later in the chapter, but even without injury or exercise, about 5 to 10 percent of the skeleton is remodeled annually just by destroying old bone and renewing it with fresh bone.

Diseases of the…Skeletal System

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a genetic disease in which bones do not form properly and therefore are fragile and break easily. It is also called brittle bone disease. The disease is present from birth and affects a person throughout life.

The genetic mutation that causes OI affects the body’s production of collagen, one of the critical components of bone matrix. The severity of the disease can range from mild to severe. Those with the most severe forms of the disease sustain many more fractures than those with a mild form. Frequent and multiple fractures typically lead to bone deformities and short stature. Bowing of the long bones and curvature of the spine are also common in people afflicted with OI. Curvature of the spine makes breathing difficult because the lungs are compressed.

Because collagen is such an important structural protein in many parts of the body, people with OI may also experience fragile skin, weak muscles, loose joints, easy bruising, frequent nosebleeds, brittle teeth, blue sclera, and hearing loss. There is no known cure for OI. Treatment focuses on helping the person retain as much independence as possible while minimizing fractures and maximizing mobility. Toward that end, safe exercises, like swimming, in which the body is less likely to experience collisions or compressive forces, are recommended. Braces to support legs, ankles, knees, and wrists are used as needed. Canes, walkers, or wheelchairs can also help compensate for weaknesses.

When bones do break, casts, splints, or wraps are used. In some cases, metal rods may be surgically implanted into the long bones of the arms and legs. Research is currently being conducted on using bisphosphonates to treat OI. Smoking and being overweight are especially risky in people with OI, since smoking is known to weaken bones, and extra body weight puts additional stress on the bones.

Interactive Link

Watch this video to see how a bone grows.

Calcium Homeostasis: Interactions of the Skeletal System and Other Organ Systems

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the effect of too much or too little calcium on the body

- Explain the process of calcium homeostasis

Calcium is not only the most abundant mineral in bone, it is also the most abundant mineral in the human body. Calcium ions are needed not only for bone mineralization but for tooth health, regulation of the heart rate and strength of contraction, blood coagulation, contraction of smooth and skeletal muscle cells, and regulation of nerve impulse conduction. The normal level of calcium in the blood is about 10 mg/dL. When the body cannot maintain this level, a person will experience hypo- or hypercalcemia.

Hypocalcemia, a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of calcium, can have an adverse effect on a number of different body systems including circulation, muscles, nerves, and bone. Without adequate calcium, blood has difficulty coagulating, the heart may skip beats or stop beating altogether, muscles may have difficulty contracting, nerves may have difficulty functioning, and bones may become brittle. The causes of hypocalcemia can range from hormonal imbalances to an improper diet. Treatments vary according to the cause, but prognoses are generally good.

Conversely, in hypercalcemia, a condition characterized by abnormally high levels of calcium, the nervous system is underactive, which results in lethargy, sluggish reflexes, constipation and loss of appetite, confusion, and in severe cases, coma.

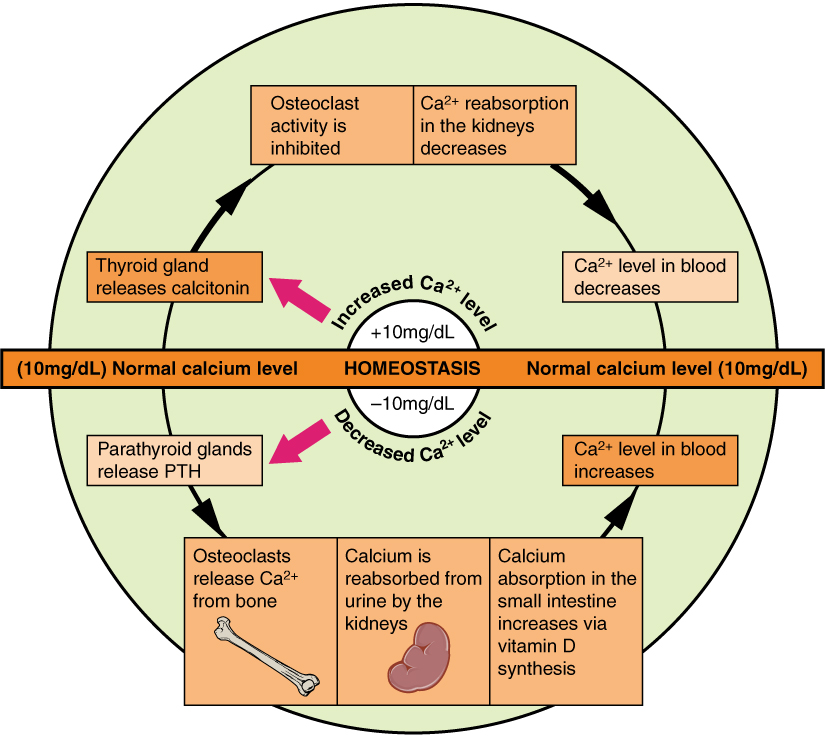

Obviously, calcium homeostasis is critical. The skeletal, endocrine, and digestive systems play a role in this, but the kidneys do, too. These body systems work together to maintain a normal calcium level in the blood (Figure 6.24).

Figure 6.24 Pathways in Calcium Homeostasis The body regulates calcium homeostasis with two pathways; one is signaled to turn on when blood calcium levels drop below normal and one is the pathway that is signaled to turn on when blood calcium levels are elevated.

Calcium is a chemical element that cannot be produced by any biological processes. The only way it can enter the body is through the diet. The bones act as a storage site for calcium: The body deposits calcium in the bones when blood levels get too high, and it releases calcium when blood levels drop too low. This process is regulated by PTH, vitamin D, and calcitonin.

Cells of the parathyroid gland have plasma membrane receptors for calcium. When calcium is not binding to these receptors, the cells release PTH, which stimulates osteoclast proliferation and resorption of bone by osteoclasts. This demineralization process releases calcium into the blood. PTH promotes reabsorption of calcium from the urine by the kidneys, so that the calcium returns to the blood. Finally, PTH stimulates the synthesis of vitamin D, which in turn, stimulates calcium absorption from any digested food in the small intestine.

When all these processes return blood calcium levels to normal, there is enough calcium to bind with the receptors on the surface of the cells of the parathyroid glands, and this cycle of events is turned off (Figure 6.24).

When blood levels of calcium get too high, the thyroid gland is stimulated to release calcitonin (Figure 6.24), which inhibits osteoclast activity and stimulates calcium uptake by the bones, but also decreases reabsorption of calcium by the kidneys. All of these actions lower blood levels of calcium. When blood calcium levels return to normal, the thyroid gland stops secreting calcitonin.

Chapter Review

The Functions of the Skeletal System

The major functions of the bones are body support, facilitation of movement, protection of internal organs, storage of minerals and fat, and hematopoiesis. Together, the muscular system and skeletal system are known as the musculoskeletal system.

Bone Classification

Bones can be classified according to their shapes. Long bones, such as the femur, are longer than they are wide. Short bones, such as the carpals, are approximately equal in length, width, and thickness. Flat bones are thin, but are often curved, such as the ribs. Irregular bones such as those of the face have no characteristic shape. Sesamoid bones, such as the patellae, are small and round, and are located in tendons.

Bone Structure

A hollow medullary cavity filled with yellow marrow runs the length of the diaphysis of a long bone. The walls of the diaphysis are compact bone. The epiphyses, which are wider sections at each end of a long bone, are filled with spongy bone and red marrow. The epiphyseal plate, a layer of hyaline cartilage, is replaced by osseous tissue as the organ grows in length. The medullary cavity has a delicate membranous lining called the endosteum. The outer surface of bone, except in regions covered with articular cartilage, is covered with a fibrous membrane called the periosteum. Flat bones consist of two layers of compact bone surrounding a layer of spongy bone. Bone markings depend on the function and location of bones. Articulations are places where two bones meet. Projections stick out from the surface of the bone and provide attachment points for tendons and ligaments. Holes are openings or depressions in the bones.

Bone matrix consists of collagen fibers and organic ground substance, primarily hydroxyapatite formed from calcium salts. Osteogenic cells develop into osteoblasts. Osteoblasts are cells that make new bone. They become osteocytes, the cells of mature bone, when they get trapped in the matrix. Osteoclasts engage in bone resorption. Compact bone is dense and composed of osteons, while spongy bone is less dense and made up of trabeculae. Blood vessels and nerves enter the bone through the nutrient foramina to nourish and innervate bones.

Bone Formation and Development

All bone formation is a replacement process. Embryos develop a cartilaginous skeleton and various membranes. During development, these are replaced by bone during the ossification process. In intramembranous ossification, bone develops directly from sheets of mesenchymal connective tissue. In endochondral ossification, bone develops by replacing hyaline cartilage. Activity in the epiphyseal plate enables bones to grow in length. Modeling allows bones to grow in diameter. Remodeling occurs as bone is resorbed and replaced by new bone. Osteogenesis imperfecta is a genetic disease in which collagen production is altered, resulting in fragile, brittle bones.

Fractures: Bone Repair

Fractured bones may be repaired by closed reduction or open reduction. Fractures are classified by their complexity, location, and other features. Common types of fractures are transverse, oblique, spiral, comminuted, impacted, greenstick, open (or compound), and closed (or simple). Healing of fractures begins with the formation of a hematoma, followed by internal and external calli. Osteoclasts resorb dead bone, while osteoblasts create new bone that replaces the cartilage in the calli. The calli eventually unite, remodeling occurs, and healing is complete.

Exercise, Nutrition, Hormones, and Bone Tissue

Mechanical stress stimulates the deposition of mineral salts and collagen fibers within bones. Calcium, the predominant mineral in bone, cannot be absorbed from the small intestine if vitamin D is lacking. Vitamin K supports bone mineralization and may have a synergistic role with vitamin D. Magnesium and fluoride, as structural elements, play a supporting role in bone health. Omega-3 fatty acids reduce inflammation and may promote production of new osseous tissue. Growth hormone increases the length of long bones, enhances mineralization, and improves bone density. Thyroxine stimulates bone growth and promotes the synthesis of bone matrix. The sex hormones (estrogen and testosterone) promote osteoblastic activity and the production of bone matrix, are responsible for the adolescent growth spurt, and promote closure of the epiphyseal plates. Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by decreased bone mass that is common in aging adults. Calcitriol stimulates the digestive tract to absorb calcium and phosphate. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) stimulates osteoclast proliferation and resorption of bone by osteoclasts. Vitamin D plays a synergistic role with PTH in stimulating the osteoclasts. Additional functions of PTH include promoting reabsorption of calcium by kidney tubules and indirectly increasing calcium absorption from the small intestine. Calcitonin inhibits osteoclast activity and stimulates calcium uptake by bones.

Calcium Homeostasis: Interactions of the Skeletal System and Other Organ Systems

Calcium homeostasis, i.e., maintaining a blood calcium level of about 10 mg/dL, is critical for normal body functions. Hypocalcemia can result in problems with blood coagulation, muscle contraction, nerve functioning, and bone strength. Hypercalcemia can result in lethargy, sluggish reflexes, constipation and loss of appetite, confusion, and coma. Calcium homeostasis is controlled by PTH, vitamin D, and calcitonin and the interactions of the skeletal, endocrine, digestive, and urinary systems.

Critical Thinking Questions

The skeletal system is composed of bone and cartilage and has many functions. Choose three of these functions and discuss what features of the skeletal system allow it to accomplish these functions.

What are the structural and functional differences between a tarsal and a metatarsal?

What are the structural and functional differences between the femur and the patella?

If the articular cartilage at the end of one of your long bones were to degenerate, what symptoms do you think you would experience? Why?

In what ways is the structural makeup of compact and spongy bone well suited to their respective functions?

In what ways do intramembranous and endochondral ossification differ?

If you were a dietician who had a young female patient with a family history of osteoporosis, what foods would you suggest she include in her diet? Why?

During the early years of space exploration our astronauts, who had been floating in space, would return to earth showing significant bone loss dependent on how long they were in space. Discuss how this might happen and what could be done to alleviate this condition.

Describe the effects caused when the parathyroid gland fails to respond to calcium bound to its receptors.

Key Terms

articular cartilage

thin layer of cartilage covering an epiphysis; reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber

articulation

where two bone surfaces meet

bone

hard, dense connective tissue that forms the structural elements of the skeleton

canaliculi

(singular = canaliculus) channels within the bone matrix that house one of an osteocyte’s many cytoplasmic extensions that it uses to communicate and receive nutrients

cartilage

semi-rigid connective tissue found on the skeleton in areas where flexibility and smooth surfaces support movement

central canal

longitudinal channel in the center of each osteon; contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels; also known as the Haversian canal

compact bone

dense osseous tissue that can withstand compressive forces

diaphysis

tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of a long bone

diploë

layer of spongy bone, that is sandwiched between two the layers of compact bone found in flat bones

endochondral ossification

process in which bone forms by replacing hyaline cartilage

endosteum

delicate membranous lining of a bone’s medullary cavity

epiphyseal line

completely ossified remnant of the epiphyseal plate

epiphyseal plate

(also, growth plate) sheet of hyaline cartilage in the metaphysis of an immature bone; replaced by bone tissue as the organ grows in length

epiphysis

wide section at each end of a long bone; filled with spongy bone and red marrow

flat bone

thin and curved bone; serves as a point of attachment for muscles and protects internal organs

fracture

broken bone

fracture hematoma

blood clot that forms at the site of a broken bone

hematopoiesis

production of blood cells, which occurs in the red marrow of the bones

hole

opening or depression in a bone

hypercalcemia

condition characterized by abnormally high levels of calcium

hypocalcemia

condition characterized by abnormally low levels of calcium

intramembranous ossification

process by which bone forms directly from mesenchymal tissue

irregular bone

bone of complex shape; protects internal organs from compressive forces

lacunae

(singular = lacuna) spaces in a bone that house an osteocyte

long bone

cylinder-shaped bone that is longer than it is wide; functions as a lever

medullary cavity

hollow region of the diaphysis; filled with yellow marrow

modeling

process, during bone growth, by which bone is resorbed on one surface of a bone and deposited on another

nutrient foramen

small opening in the middle of the external surface of the diaphysis, through which an artery enters the bone to provide nourishment

osseous tissue

bone tissue; a hard, dense connective tissue that forms the structural elements of the skeleton

ossification

(also, osteogenesis) bone formation

ossification center

cluster of osteoblasts found in the early stages of intramembranous ossification

osteoblast

cell responsible for forming new bone

osteoclast

cell responsible for resorbing bone

osteocyte

primary cell in mature bone; responsible for maintaining the matrix

osteogenic cell

undifferentiated cell with high mitotic activity; the only bone cells that divide; they differentiate and develop into osteoblasts

osteoid

uncalcified bone matrix secreted by osteoblasts

osteon

(also, Haversian system) basic structural unit of compact bone; made of concentric layers of calcified matrix

osteoporosis

disease characterized by a decrease in bone mass; occurs when the rate of bone resorption exceeds the rate of bone formation, a common occurrence as the body ages

perforating canal

(also, Volkmann’s canal) channel that branches off from the central canal and houses vessels and nerves that extend to the periosteum and endosteum

periosteum

fibrous membrane covering the outer surface of bone and continuous with ligaments

primary ossification center

region, deep in the periosteal collar, where bone development starts during endochondral ossification

projection

bone markings where part of the surface sticks out above the rest of the surface, where tendons and ligaments attach

proliferative zone

region of the epiphyseal plate that makes new chondrocytes to replace those that die at the diaphyseal end of the plate and contributes to longitudinal growth of the epiphyseal plate

red marrow

connective tissue in the interior cavity of a bone where hematopoiesis takes place

remodeling

process by which osteoclasts resorb old or damaged bone at the same time as and on the same surface where osteoblasts form new bone to replace that which is resorbed

sesamoid bone

small, round bone embedded in a tendon; protects the tendon from compressive forces

short bone

cube-shaped bone that is approximately equal in length, width, and thickness; provides limited motion

skeletal system

organ system composed of bones and cartilage that provides for movement, support, and protection

spongy bone

(also, cancellous bone) trabeculated osseous tissue that supports shifts in weight distribution

trabeculae

(singular = trabecula) spikes or sections of the lattice-like matrix in spongy bone

yellow marrow

connective tissue in the interior cavity of a bone where fat is stored

zone of calcified matrix

region of the epiphyseal plate closest to the diaphyseal end; functions to connect the epiphyseal plate to the diaphysis

zone of maturation and hypertrophy

region of the epiphyseal plate where chondrocytes from the proliferative zone grow and mature and contribute to the longitudinal growth of the epiphyseal plate