4.2 History of Newspapers

Over its long and complex history, the newspaper has undergone many transformations. Examining the historical roots of newspapers can help shed light on how and why they have evolved into a multifaceted medium. Scholars commonly credit the ancient Romans with publishing the first newspaper-like product, the Acta Diurna, or “daily doings,” in 59 BCE. Carved on stone or metal and presented on message boards in public places, such as the Roman Forum, historians speculate that the Romans published chronicles of events, assemblies, births, deaths, and daily gossip.

In 1566, another ancestor of the modern newspaper appeared in Venice, Italy. These handwritten avisi, or gazettes, focused on politics and military conflicts. However, the absence of printing press technology greatly limited the circulation of the Acta Diurna and the Venetian papers.

As discussed in the previous chapter, Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press drastically changed the face of publishing. In 1440, Gutenberg invented a movable-type press that permitted the high-quality reproduction of printed materials at a rate of nearly 4,000 pages per day, or 1,000 times more than a scribe could complete by hand. This innovation drove down the price of printed materials and, for the first time, made them accessible to a mass market. Overnight, the new printing press transformed the scope and reach of the newspaper, paving the way for modern-day journalism.

European Roots

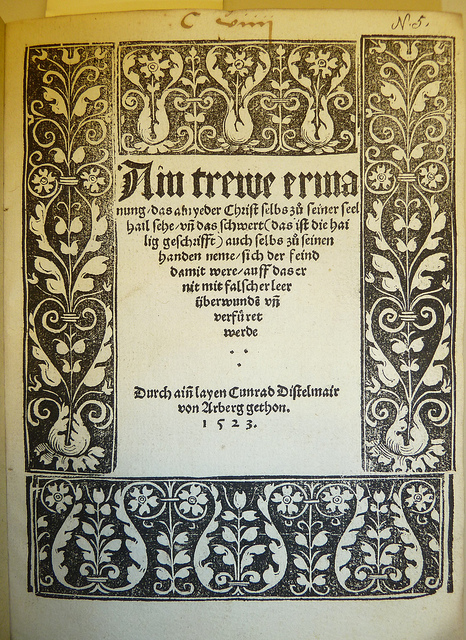

The first weekly newspapers to employ Gutenberg’s press emerged in 1609. Although the papers—Relations: Aller Furnemmen, printed by Johann Carolus, and Aviso Relations over Zeitung, printed by Lucas Schulte—did not name their cities of publication to avoid government persecution, their use of the German language helped identify their approximate location. Despite these concerns over persecution, the papers proved successful, and newspapers quickly spread throughout Central Europe. Over the next five years, weeklies popped up in Basel, Frankfurt, Vienna, Hamburg, Berlin, and Amsterdam. In 1621, England printed its first paper under the title Corante, or weekely newes from Italy, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Bohemia, France and the Low Countreys. By 1641, almost every country in Europe had a newspaper, as the printing press had spread to France, Italy, and Spain.

These early newspapers followed one of two major formats. The Dutch-style corantos densely packed reading material into a two- to four-page paper, while the German-style pamphlet (or broadside) offered a more expansive eight- to 24-page paper. Many publishers began printing in the Dutch format, but as their popularity grew, they changed to the larger German broadside style.

Government Control and Freedom of the Press

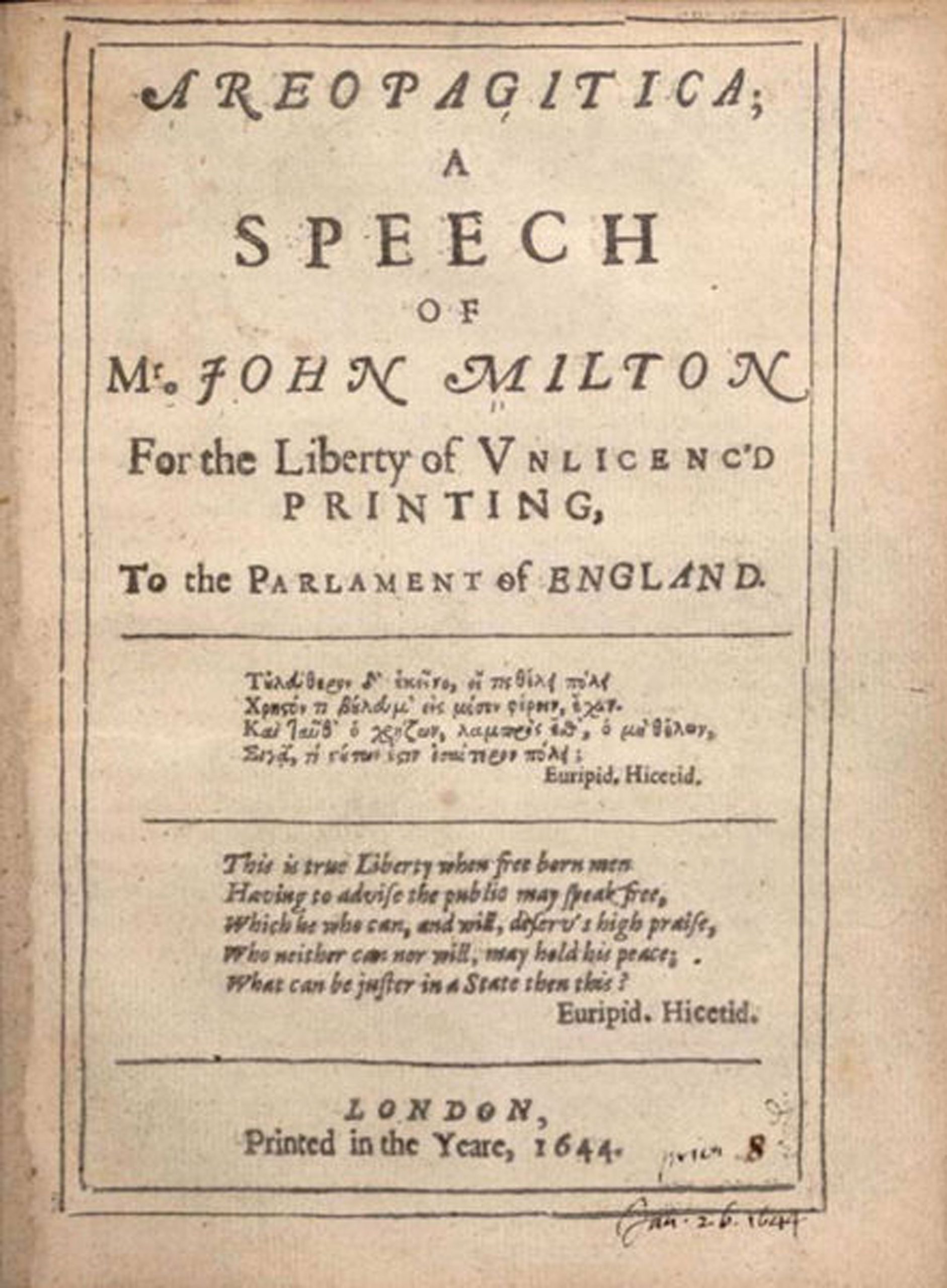

Because the government regulated many of these early publications, they did not report on local news or events. However, civil war broke out in England in 1641. As Oliver Cromwell and Parliament threatened and eventually overthrew King Charles I, citizens turned to local papers for coverage of these major events. In November 1641, a weekly paper titled The Heads of Severall Proceedings in This Present Parliament began focusing on domestic news (Goff, 2007). The paper fueled a discussion about the freedom of the press that John Milton later articulated in 1644 in his famous treatise Areopagitica.

Although the arguments in Areopagitica focused primarily on Parliament’s ban on certain books, it also addressed newspapers. Milton criticized the tight regulations on their content by stating, “Who kills a man kills a reasonable creature, God’s image; but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye (Milton, 1644).” Despite Milton’s emphasis on texts rather than on newspapers, the treatise had a major effect on printing regulations. In England, newspapers were freed from government control, and people began to understand the power of a free press.

Papers took advantage of this newfound freedom and began publishing more frequently. With biweekly publications, papers had additional space to run advertisements and market reports. This changed the role of journalists from simple observers to active players in commerce, as business owners and investors grew to rely on the papers to market their products and to help them predict business developments. Once publishers noticed the growing popularity and profit potential of newspapers, they founded daily publications. In 1650, a German publisher began printing the world’s oldest daily paper, Einkommende Zeitungen, and an English publisher followed suit in 1702 with London’s Daily Courant. Such daily publications, which employed the relatively new format of headlines and the embellishment of illustrations, turned papers into vital fixtures in the everyday lives of citizens.

Colonial American Newspapers

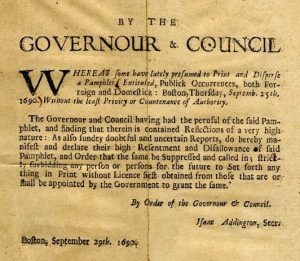

Newspapers did not come to the American colonies until September 25, 1690, when Benjamin Harris printed Publick Occurrences, Both FORREIGN and DOMESTICK. Harris had worked as a newspaper editor in England before fleeing to America after he published an article about a purported Catholic plot against England. The first article printed in his new colonial paper stated, “The Christianized Indians in some parts of Plimouth, have newly appointed a day of thanksgiving to God for his Mercy (Harris, 1690).” The other articles in Publick Occurrences, however, shared similarities with Harris’s previously more controversial style (for instance, he suggested King William “used to lie with the Son’s Wife”). The publication folded after just one issue, and the government ordered all copies to be destroyed.

Fourteen years passed before the next American newspaper, The Boston News-Letter, was launched. Fifteen years after that, the Boston Gazette began publication, followed immediately by the American Weekly Mercury in Philadelphia. Trying to avoid following in Harris’s footsteps, these early papers carefully eschewed political discussion to avoid offending colonial authorities. After a lengthy absence, politics reentered American papers in 1721, when James Franklin published a criticism of smallpox inoculations in the New England Courant. The following year, the paper accused the colonial government of failing to protect its citizens from pirates, which resulted in Franklin’s imprisonment.

After Franklin offended authorities once again for mocking religion, a court dictated that he could no longer “print or publish The New England Courant, or any other Pamphlet or Paper of the like Nature, except it be first Supervised by the Secretary of this Province (Massachusetts Historical Society).” Immediately following this order, Franklin turned over the paper to his younger brother, Benjamin. Benjamin Franklin, who went on to become a renowned statesman and played a pivotal role in the American Revolution, also had a substantial impact on the printing industry as the publisher of The Pennsylvania Gazette and the creator of subscription libraries.

Journalism and news reporting during the colonial period in American history differed significantly from modern practices. Early newspapers were primarily concentrated in port cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, serving as vital sources of information for merchants and the business community. These publications typically prioritized business news, shipping reports, and advertisements, reflecting the economic focus of the colonies. However, the number of newspapers was limited in the early colonial period, and many struggled to survive financially due to factors such as high production costs, limited distribution networks, government censorship, and increasing competition.

The newspapers of the time did not resemble their modern counterparts. Objective coverage was rare, and many publications openly expressed partisan viewpoints, which could be considered libelous by today’s standards. Colonial papers sometimes included satire, literary excerpts, poetry, and even serialized fiction. They often focused on stories that concerned trade, British politics, and European affairs, though as the colonies matured, local news became more prevalent. While newspapers were more accessible to wealthier and more educated colonists, they were also read by a broader segment of society, including merchants, clergy, and some artisans and tradespeople; however, limited literacy and high costs restricted their wider circulation.

As the American Revolution drew near, newspapers became increasingly partisan, serving as vital tools for disseminating political ideologies. Patriot publications, such as Isaiah Thomas’s The Massachusetts Spy and the Journal of Occurrences, helped inform colonists about perceived British misdeeds and rallied support for resistance, often aligning with the activities of groups like the Sons of Liberty. On the Loyalist (Tory) side, newspapers such as James Rivington’s Royal Gazette defended British policies and the authority of the Crown. While some colonists initially sought reconciliation and greater representation within the existing British system, this position became increasingly untenable as tensions escalated. As the revolution drew closer, Loyalist papers faced growing hostility, threats, and even violence, leading to the closure of some publications. At the same time, Patriot newspapers gained significant influence and fueled the revolutionary movement.

The Trial of John Peter Zenger

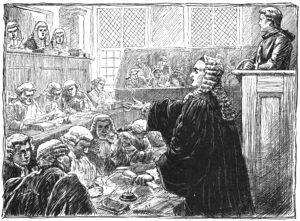

Political discussions began to appear in other newspapers around the colonies. In 1733, John Peter Zenger founded The New York Weekly Journal. Zenger’s paper soon began criticizing the newly appointed colonial governor, William Cosby, who had replaced members of the New York Supreme Court when he could not control them. In late 1734, Cosby had Zenger arrested, claiming that his paper contained “divers scandalous, virulent, false and seditious reflections (Archiving Early America).” Eight months later, prominent Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton defended Zenger in a groundbreaking trial. Hamilton compelled the jury to consider the truth and determine whether Zenger had printed factual statements. Ignoring the judge’s disapproval of Zenger and his actions, the jury returned a not-guilty verdict to the courtroom after only a short deliberation. Zenger’s trial resulted in two significant developments in the march toward press freedom. First, the prosecution demonstrated to the papers that they could potentially print honest criticism of the government without fear of retribution. Second, the British became afraid that an American jury would never convict an American journalist.

With Zenger’s verdict providing more freedom to the press, some began to call for emancipation from England, and newspapers became their conduit for political discussion.

Freedom of the Press in the Early United States

The Stamp Act of 1765, which imposed a tax on various paper goods, including newsprint, created significant economic hardship for colonial newspapers. While the British government claimed to be taxing the physical paper and not the ideas contained within, the act was widely seen as an attempt to suppress dissent. Some newspapers temporarily suspended publication in protest, while others continued to publish, sometimes defying the tax outright.

In 1791, the nascent United States of America adopted the First Amendment as part of the Bill of Rights. This act states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceable to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances (Cornell University Law School).” In this one sentence, U.S. law formally guaranteed freedom of the press. The Stamp Act’s impact on the Founding Fathers in creating this legislation cannot be overstated. It solidified the notion that a free press is essential for a functioning democracy and catalyzed the American Revolution.

However, as a reaction to harsh partisan writing, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Act in 1798, which declared that “writing, printing, uttering, or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States” was punishable by fine and imprisonment (Constitution Society, 1798). When Thomas Jefferson won the presidency in 1800, he allowed the Sedition Act to lapse, claiming the country would undergo “a great experiment…to demonstrate the falsehood of the pretext that freedom of the press is incompatible with orderly government (University of Virginia).” This free press experiment has continued to the present day.

As late as the early 1800s, newspapers still required extensive expenses to print. Although daily papers had become more common and gave merchants up-to-date, vital trading information, most cost about 6 cents a copy, well above what artisans and other working-class citizens could afford. As such, newspaper readership did not extend beyond the elite.

All that changed in September 1833 when Benjamin Day created The Sun. Printed on small, letter-sized pages, The Sun sold for just a penny. With the Industrial Revolution in full swing, Day employed the new steam-driven, two-cylinder press to print The Sun. While the old printing press could print approximately 125 newspapers per hour, this technologically improved version printed approximately 18,000 copies per hour. As he reached out to new readers, Day knew that he wanted to alter the concept of news, which had heavily featured inflammatory partisan commentary up until that point. He printed the paper’s motto at the top of every front page of The Sun: “The object of this paper is to lay before the public, at a price within the means of every one, all the news of the day, and at the same time offer an advantageous medium for advertisements (Starr, 2004).”

The Sun sought out stories that would appeal to the new mainstream consumer. As such, the paper primarily published human-interest stories and police reports. Additionally, Day left ample room for advertisements. Day’s adoption of this new format and industrialized method of printing proved highly successful. The Sun became the first paper of what became known as the penny press. Before the emergence of the penny press, the most popular paper, New York City’s Courier and Enquirer, had sold 4,500 copies per day. By 1835, The Sun sold 15,000 copies per day.

The Sun would eventually compete with another early successful penny paper, James Gordon Bennett’s New York Morning Herald, which debuted in 1835. Bennett made his mark on the publishing industry by offering nonpartisan political reporting. He also introduced more aggressive methods for gathering news, hiring both interviewers and foreign correspondents. His paper became the first to send a reporter to a crime scene to witness an investigation. In the 1860s, Bennett hired 63 war reporters to cover the U.S. Civil War. Although the Herald initially emphasized sensational news, it later became one of the country’s most respected papers for its accurate reporting.

The Abolitionist Press

The abolitionist press played a vital role in the anti-slavery movement in the United States from the 1830s to the Civil War. It served as a crucial platform for disseminating anti-slavery ideas, mobilizing public opinion, and organizing abolitionist activities. Unlike the mainstream press of the time, which often ignored or even supported slavery, the abolitionist press provided a powerful counter-narrative, exposing the horrors of slavery and advocating for its immediate abolition.

The abolitionist press attempted to appeal to the public’s conscience by highlighting the moral and religious wrongness of slavery. They published narratives of enslaved people, accounts of the brutality of slavery, and arguments based on spiritual and ethical principles in a wide range of publications, from weekly newspapers to pamphlets and books. It included voices from both Black and white abolitionists, as well as men and women. Compared to more moderate anti-slavery efforts, the abolitionist press often took a radical stance, demanding immediate and unconditional emancipation. This radicalism usually put them at odds with both pro-slavery forces and more gradualist anti-slavery advocates.

Freedom’s Journal, founded in New York City by John Russwurm and Samuel Cornish, is considered the first African American-owned and operated newspaper in the United States. It addressed issues of slavery and racial discrimination, providing a platform for Black voices and perspectives. Though short-lived, it set a precedent for future Black-owned newspapers and played a crucial role in early Black activism.

William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, published in Boston, became one of the most influential and uncompromising voices in the abolitionist movement. Garrison’s advocacy for immediate emancipation made him a controversial figure, but his newspaper played a pivotal role in galvanizing the abolitionist cause. Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved man and powerful orator, established The North Star in Rochester, New York. His newspaper provided a crucial platform for Black perspectives on slavery and other social issues. Douglass’s eloquent writing and powerful arguments made The North Star a leading voice in the abolitionist movement.

Abolitionist publishers faced significant challenges, including financial difficulties, censorship, and violent attacks. Presbyterian minister Elijah Lovejoy published the Alton Observer in Alton, Illinois, a border state with strong pro-slavery sentiment. Lovejoy’s outspoken condemnation of slavery made him a target of pro-slavery mobs. He lost his life in 1837 while defending his printing press from an angry mob, becoming a martyr for the abolitionist cause and freedom of the press.

Despite such setbacks, the Abolitionist Press laid the groundwork for the Civil War and demonstrated the power of the press to challenge injustice and advocate for social change.

Growth of Wire Services and Printing Capacity

Another major historical technological breakthrough for newspapers came when Samuel Morse helped improve the electric telegraph in 1837. Newspapers turned to emerging telegraph companies to receive up-to-date news briefs from cities across the globe. The significant expense of this service led to the formation of the Associated Press (AP) in 1846 as a cooperative arrangement of five major New York papers: the New York Sun, the Journal of Commerce, the Courier and Enquirer, the New York Herald, and the Express. The success of the Associated Press led to the development of wire services between major cities. According to the AP, this meant that editors were able to “actively collect news as it [broke], rather than gather already published news (Associated Press).” This collaboration between papers allowed for more reliable reporting, and the increased breadth of subject matter lent subscribing newspapers mass appeal for not only upper- but also middle- and working-class readers.

The invention of the steam-powered printing press in the early 19th century revolutionized the newspaper industry, drastically increasing production speed and lowering costs. Before this innovation, printing relied on manual labor using hand-operated presses, a slow and laborious process that limited the circulation and availability of newspapers. The steam press, pioneered by figures like Friedrich Koenig, automated the printing process, allowing for the printing of hundreds, and eventually thousands, of pages per hour.

This technological leap had profound consequences for journalism. Increased printing speed enabled newspapers to reach a much wider audience, leading to the rise of mass-circulation newspapers and the emergence of the Penny Press. Lower production costs made newspapers more affordable, expanding readership beyond the elite and fostering greater public access to information. This wider news dissemination contributed to increased literacy rates and a more informed public discourse. The steam press also enabled newspapers to include more content, leading to larger and more comprehensive publications. With the growth of railroads and steamboats, news could now travel quicker than ever.

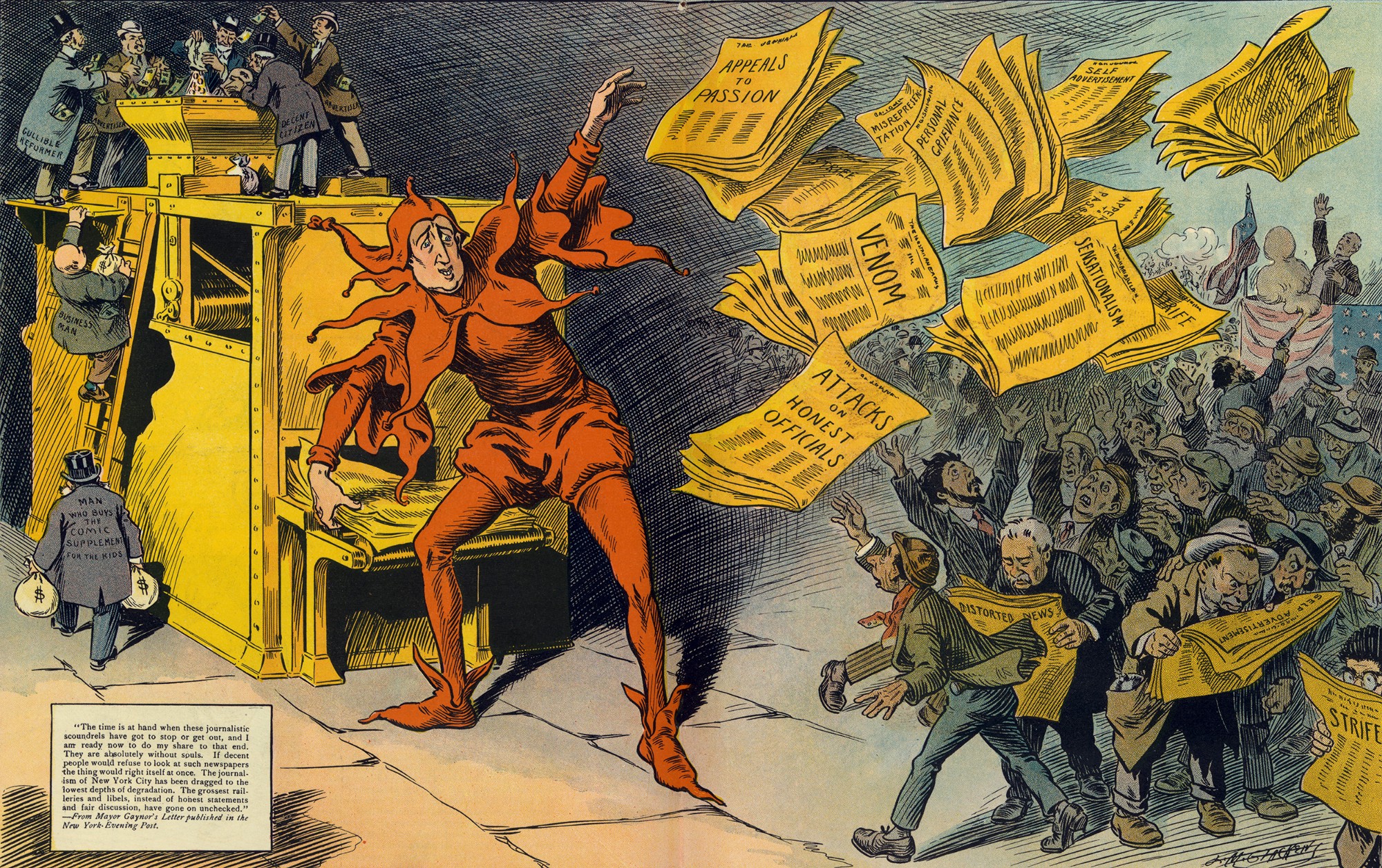

Yellow Journalism

In the late 1800s, Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World, developed a new journalistic style that relied on an intensified use of sensationalism—stories focused on crime, violence, emotion, and sex. Although he made major strides in the newspaper industry by creating an expanded section focusing on women and pioneering the use of advertisements as news, Pulitzer relied primarily on violence and sex in his headlines to sell more copies. Ironically, journalism named its most prestigious award after him. His New York World became famous for such headlines as “Baptized in Blood” and “Little Lotta’s Lovers (Fang, 1997).” This sensationalist style served as the forerunner for today’s tabloids. Editors relied on shocking headlines to sell their papers, and although investigative journalism filled the pages, editors often took liberties with how they told the story. Newspapers usually printed an editor’s interpretation of the story without maintaining objectivity.

At the same time, Pulitzer had established the New York World, William Randolph Hearst—an admirer and principal competitor of Pulitzer—took over the New York Journal. The battle between these two major New York newspapers escalated as Pulitzer and Hearst attempted to outdo one another. The papers slashed their prices back down to a penny, stole editors and reporters from each other, and filled their papers with outrageous, sensationalist headlines. Both shared an equal passion for motivating the United States to go to war with Spain, and they succeeded with the declaration of the Spanish-American War. Both Hearst and Pulitzer filled their papers with huge front-page headlines and gave bloody—if sometimes inaccurate—accounts of the war. As historian Richard K. Hines writes, “The American Press, especially ‘yellow presses’ such as William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal [and] Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World … sensationalized the brutality of the reconcentrado and the threat to American business interests. Journalists frequently embellished Spanish atrocities and invented others (Hines, 2002).” Hearst’s life partially inspired the 1941 classic film Citizen Kane.

Kid Blink’s Uprising: How Newsies Took on Giants

Newsies were a ubiquitous presence in American cities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These young children, primarily boys, hawked newspapers on street corners, shouting headlines and vying for the attention of passersby. They played a vital part in distributing newspapers, particularly for evening editions, and their cries were a familiar soundtrack of urban life.

Life as a newsie was far from glamorous. The children worked long hours, often in harsh weather conditions, for meager earnings. Newsies typically purchased their newspapers from publishers at a wholesale price and then resold them for a small profit. This meant they bore the risk of unsold papers, which cut into their already slim earnings.

In 1899, this precarious existence led to the Newsboys Strike in New York City. Led by Kid Blink (Louis Baletti), a charismatic young newsie with a legendary eye patch, the strike was sparked by a price increase imposed by influential publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. Pulitzer’s New York World and Hearst’s New York Journal had been engaged in a fierce circulation war, driving down the price of newspapers to attract readers. However, when the Spanish-American War ended, they colluded to raise the price they charged newsies, squeezing their already tight margins.

The newsies, many of whom were impoverished and homeless, organized a strike, refusing to sell the World and Journal. They formed a union, held rallies, and even disrupted the publishers’ distribution efforts. The strike garnered public sympathy and media attention, putting pressure on the publishers to negotiate.

After two weeks, the strike ended in a partial victory for the newsies. While they didn’t achieve a complete rollback of the price increase, they won a significant concession: the right to return unsold papers for a refund. This reduced their financial risk and improved their working conditions.

The Newsboys Strike of 1899 is a remarkable example of child labor activism and the power of collective action. It highlights the struggles faced by working children in the Industrial Age and their ability to organize and fight for their rights. The strike also highlights the role of newspapers in shaping public discourse and the power of public opinion to influence even the most powerful media moguls.

Comics and Stunt Journalism

As the publishers vied for readership, newspapers introduced an entertaining new element to their pages: the comic strip. In 1896, Hearst’s New York Journal published R. F. Outcault’s the Yellow Kid in an attempt to “attract immigrant readers who otherwise might not have bought an English-language paper (Yaszek, 1994).” Readers rushed to buy papers featuring the successful, yellow nightshirt-wearing character. The cartoon “provoked a wave of ‘gentle hysteria,’ and soon began to appear on buttons, cracker tins, cigarette packs, and ladies’ fans—and even as a character in a Broadway play (Yaszek, 1994).” The cartoon’s popularity gave rise to the term yellow journalism to describe the types of papers in which it appeared.

Pulitzer responded to the success of the Yellow Kid by introducing a new form of journalism, known as stunt journalism. The publisher hired journalist Elizabeth Cochrane, who wrote under the name Nellie Bly, to report on aspects of life that the publishing industry had previously ignored. Her first article focused on the New York City Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell Island. Bly feigned insanity and had herself committed to the infamous asylum. She recounted her experience in her first article, “Ten Days in a Madhouse.” “It was a brilliant move. Her madhouse performance inaugurated the performative tactic that would become her trademark reporting style (Lutes, 2002).”

Such articles brought Bly much notoriety and fame, and she became known as the first stunt journalist. Some considered her stunts lowbrow entertainment, and more traditional journalists often criticized female stunt reporters. Regardless, Pulitzer’s decision to hire Bly represented a huge step for women in the newspaper business. Bly and her fellow stunt reporters “were the first newspaperwomen to move, as a group, from the women’s pages to the front page, from society news into political and criminal news (Lutes, 2002).”

Despite the sometimes questionable tactics of both Hearst and Pulitzer, each made significant contributions to the growing journalism industry. By 1922, Hearst, a ruthless publisher, had created the country’s largest media holding company. At that time, he owned 20 daily papers, 11 Sunday papers, two wire services, six magazines, and a newsreel company. Likewise, toward the end of his life, Pulitzer turned his focus to establishing a school of journalism. In 1912, a year after his death and 10 years after Pulitzer had initiated his educational campaign, classes were established at the Columbia University School of Journalism. At the time of its opening, the school had approximately 100 students from 21 countries. Additionally, in 1917, the Pulitzer Prize awarded its first accolades for excellence in journalism.