13.4 Compare and Contrast

The primary aim of comparing and contrasting in college writing is to clarify meaningful, non-obvious features of similarity and difference. In this case, comparison means showing similarity or likeness, and contrasting means showing difference or distinction. Comparing and contrasting is a vital skill in writing and critical thinking, and even essays that are not explicitly “compare-and-contrast” assignments require this skill as a means to clarify and sharpen your ideas.

There is no real point in explaining obvious or insignificant similarities and differences, of course, nor is there much of a point in comparing two similar subjects, or contrasting two different subjects. But this is where students most struggle with comparison and contrast: identifying obvious features or features that provide no real insight into their subjects.

For example, it would be a failure of thought and writing skills to spend time contrasting horror movies and romantic comedies by pointing out that horror movies typically involve more terror and violence than the love and hijinks of a romantic comedy. The two kinds of films are already different, so contrasting them in such a way adds no real insight. It would be an equal failure to compare horror movies and romantic comedies by pointing out that they are both genres of cinema that involve directors, producers, and actors. They are obvious similarities, so they fail to show meaningful connections.

Why do student writers so often fail in such ways? One reason is that listing the obvious is a quicker and simpler activity than real comparison and contrast, which is rigorous and requires both imaginative and critical thought. Another reason is the fear of being wrong, or of being informed that you are wrong, which is ever-present when venturing a new insight or creative idea. Instead, you must risk being wrong by seeking unique and significant connections and distinctions. And then you can do your best to use the writing process stages of revision and editing to clean out the bad ideas and sharpen the good ones. Regardless of the result, the mere act of going through this risk and process further conditions your imaginative and critical thinking, and further hones your writing skills.

Categories and Criteria

Comparison and contrast often work by engaging in classification, which means explaining how your subjects can fit a different type of category than readers would typically realize, or how your subjects should not be placed in their typically assumed categories. Although classification is often treated as a different type of writing assignment, it is often a version of comparison and contrast.

The use of categories takes a subject from one category and places it in a new category, but this classification works by drawing comparisons between the style, theme, and structure. You could take two subjects and classify them together in the same category through comparison. All of this can also be done through the lens of contrast.

Related to this use of categories is the use of criteria. Criteria are standards or qualities that candidates must meet or include. For example, criteria for a passing essay might include (1) a minimum of 2,500 words, (2) the use of MLA format, and (3) the citation of at least seven sources. Failing to meet one criterion of these three, such as the minimum word count, would mean that the essay does not fit the category of a passing essay, and it would thus fail.

Criteria can help sharpen and clarify your thinking about categories, and about how your subjects compare to and contrast with them, and with each other. You can establish criteria in your essay, explain what they are and why, and then you can apply your subjects to those criteria as candidates to see how they compare and contrast. This would be comparing and contrasting through the use of criteria.

There are many advantages to using criteria, such as the organization and expansiveness they lend automatically to essays, but this approach does add the extra stage of establishing the criteria, and that often requires rigorous critical thinking to come up with criteria that truly work.

Again, finding a new or unique category for a subject, and making that re-classification make worthwhile sense, requires both creative and critical thinking.

Conclusions and Judgments

One difficulty of comparison and contrast is that a worthwhile conclusion can sometimes seem evasive. Even if you can point out significant similarities or differences between your subjects, you might not have addressed the natural question, “So what?” What does it matter that your two similar subjects are significantly different? Or that your two different subjects are significantly similar? Especially for essays focused on contrast, this difficulty can be addressed by seeking a conclusion of judgment. That means determining which of your contrasting subjects is better, a kind of “this versus that” essay.

There are other types of conclusions available, but you must be mindful of the need to include some ultimate point or answer to, “So what?” An essay that shows its readers significant similarities and/or differences must also show them why that matters.

Organization

The compare-and-contrast essay often starts with a thesis that clearly states the subjects that are to be compared, contrasted, or both, as well as the reason for doing so. The thesis could lean more toward comparing, or contrasting, or it could focus on both equally. Remember that the point of comparing and contrasting is to provide insight to the reader. Take the following thesis as an example that leans more toward contrasting.

Here the thesis sets up the two subjects to be compared and contrasted (organic versus conventional vegetables), and it claims the results that might prove useful to the reader.

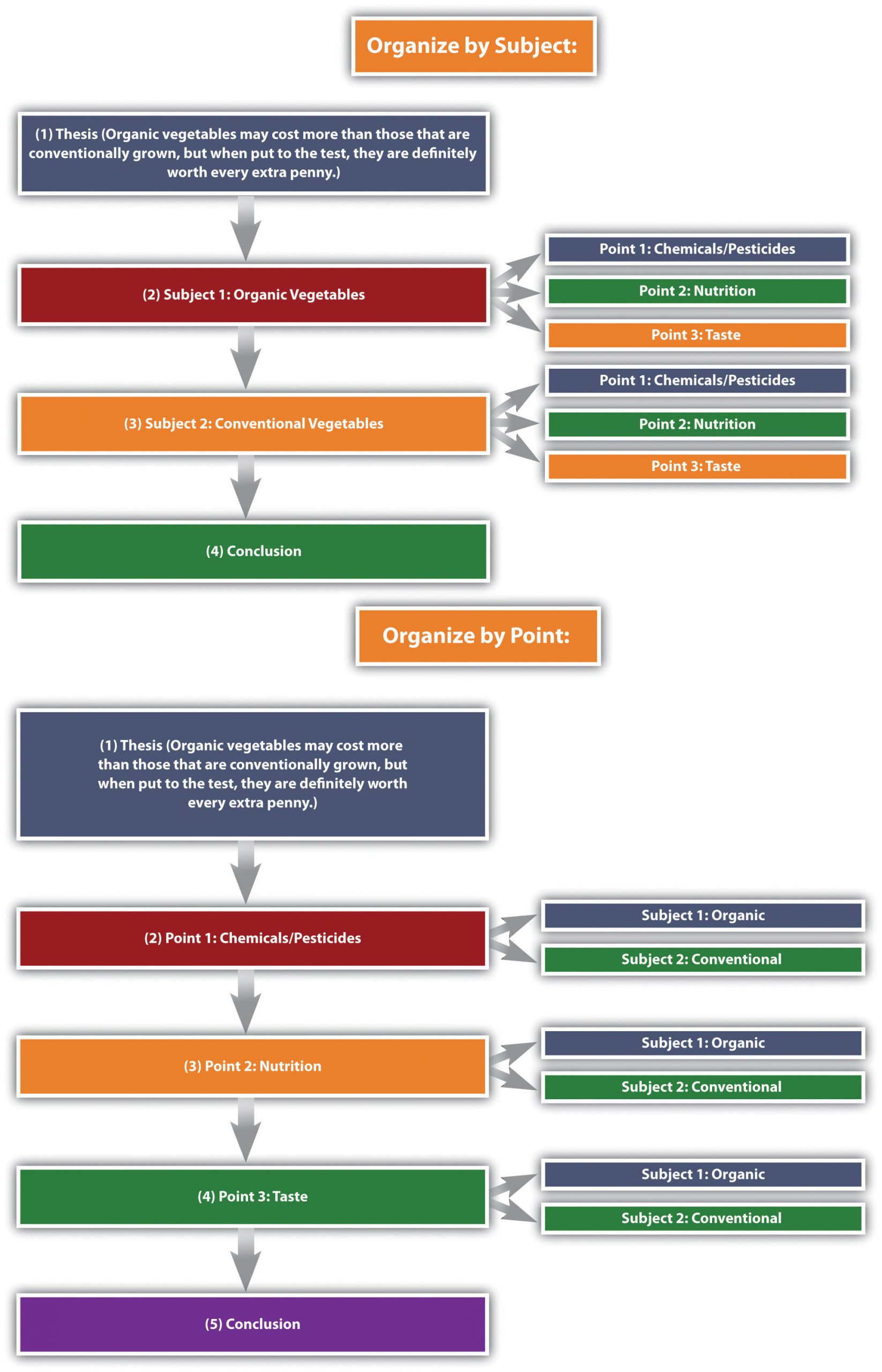

The standard compare-and-contrast essays could be organized in one of the following two ways:

- According to the subjects themselves, discussing one then the other

- According to individual points, discussing each subject about each point

The figures below diagram the two different types of typical organization, using the example of organic versus conventional vegetables.

These two types of organization apply to most types of compare-and-contrast essays, even those involving categories and criteria, which often use the second organizational strategy (organizing by points). But there are far too many possibilities and variations to say that these are the only two types of organization. Ultimately, you must make your organizational decisions based on your subject, your purpose, and your audience.

Additional Resources

- This website covers several examples of literary essays and terms. Here is their brief on Compare and Contrast Essays.

Attributions

The Writing Textbook by Josh Woods, editor and contributor, as well as an unnamed author (by request from the original publisher), and other authors named separately is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter has additions, edits, and organization by James Charles Devlin.