6.4 Improving the Five Paragraph Essay

Several new (and sometimes not-so-new) students are skilled wordsmiths and generally clear thinkers but are nevertheless stuck in a high-school style of writing. The skills that go into a very basic kind of essay—often called the five-paragraph theme—are indispensable. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clear and consistent thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and situating an argument within a broader context through the intro and conclusion. In college, you need to build on those essential skills.

The five-paragraph essay can come across as bland and formulaic. If you fall into this pitfall, your professors will be disappointed. They are looking for a more ambitious and arguable thesis, a nuanced and compelling argument, and real-life evidence for all key points, all in an organically structured paper.

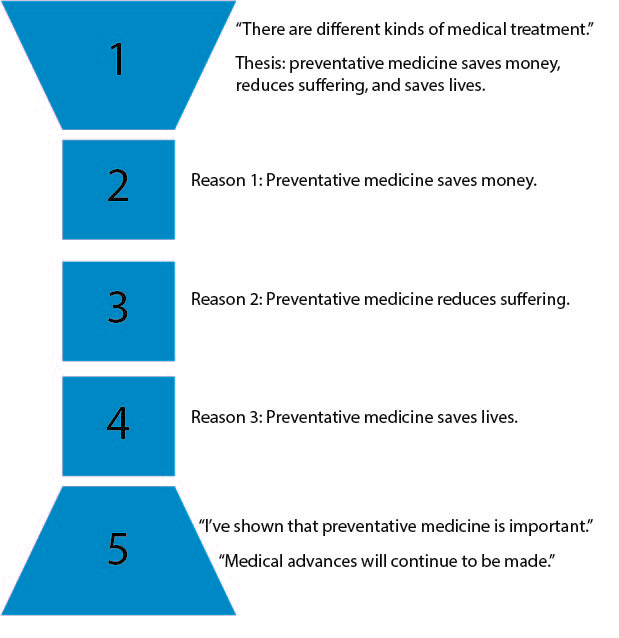

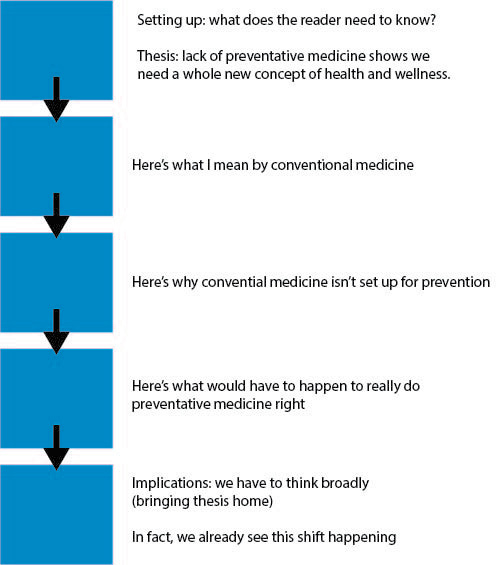

The images below contrast the standard five-paragraph theme and the organic college paper.

The five-paragraph theme, outlined in the first image, is probably what you’re used to: the introductory paragraph starts broad and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this idealized format, the thesis invokes the magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the final paragraph restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

In contrast, image two represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply positing several reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Huh. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on. The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph theme it hardly matters which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure, each paragraph specifically leads to the next.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay is driven by an ambitious, non-obvious argument, the reader comes to the concluding section thinking “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, the author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

The substantial time you spent mastering the five-paragraph was time well spent; it’s hard to imagine anyone succeeding with the more organic form without the organizational skills and habits of mind inherent in the simpler form. But if you assume that you must adhere rigidly to the simpler form, you’re blunting your intellectual ambition. Your professors will not be impressed by obvious theses, loosely related body paragraphs, and repetitive conclusions. They want you to undertake an ambitious independent analysis, one that will yield a thesis that is somewhat surprising and challenging to explain.

Attribution

Writing in College by Amy Guptill is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter has additions, edits, and organization by James Charles Devlin.