6.2 Strong Writers Still Need Revision

It is an unhealthy fiction that good writers summon forth beautiful, lean, yet intricate sentences onto a page without sweating. What writers need is revision. Novice writers, experienced writers, all writers. Anyone interested in writing clearer, stronger, more persuasive, and passionate prose, even those of us who are procrastinators, panicking because we need to get a project finished or a paper written and it’s 2:00 a.m. the night before our deadline—writers need revision because revision is not a discrete step. Revision is not the thing writers do when they’re done writing. Revision is the writing.

It’s important to keep in mind that revision is not the same step as proofreading or copyediting; no amount of grammatical, spelling, and style corrections transforms a piece of writing like focused attention to fundamental questions about purpose, evidence, and organization. Revision is the heavy lifting of working through why we are writing, who we are writing for, and how we structure writing logically and effectively.

Revision Is Writing

Writing students are usually relieved to hear that published authors often find writing just as fraught as they do. Like college students, people paid to write—the journalists and the novelists and the technical writers—more often than not despair at the difference between what’s in their heads and hearts and what ends up on the page the first time around. The professionals are just a little better at waiting things out, pushing through what Anne Lamott calls “shitty first drafts” and all the ones that follow.

Revision is not a sign of weakness, inexperience, or poor writing. The more writers push through chaos to get to the good stuff, the more they revise. The more writers revise, whether that be the keystrokes they sweat in front of a blinking, demanding cursor or the unofficial revising they do in our heads when they’re showering, driving, or running, the more the ideal reader becomes a part of their craft and muscle memory, of who they are as writers, so at some point, they may not know where the writing stops and the revision begins.

Because writing and revision are impossible to untangle, revision is just as situational and interpretive as writing. In other words, writers interact with readers—writing and revision are social, responsive, and communal. Effective revising isn’t making changes for the sake of change but instead making smarter changes. And professional writers—practiced writers—have this awareness even if they aren’t aware of it. In Stephen King’s memoir On Writing, he calls this instinct the ideal reader: an imagined person a writer knows and trusts but rewrites in response to, a kind of collaborative dance between writer and reader. To writers, the act of writing is an act of thinking.

Global and Local Revision

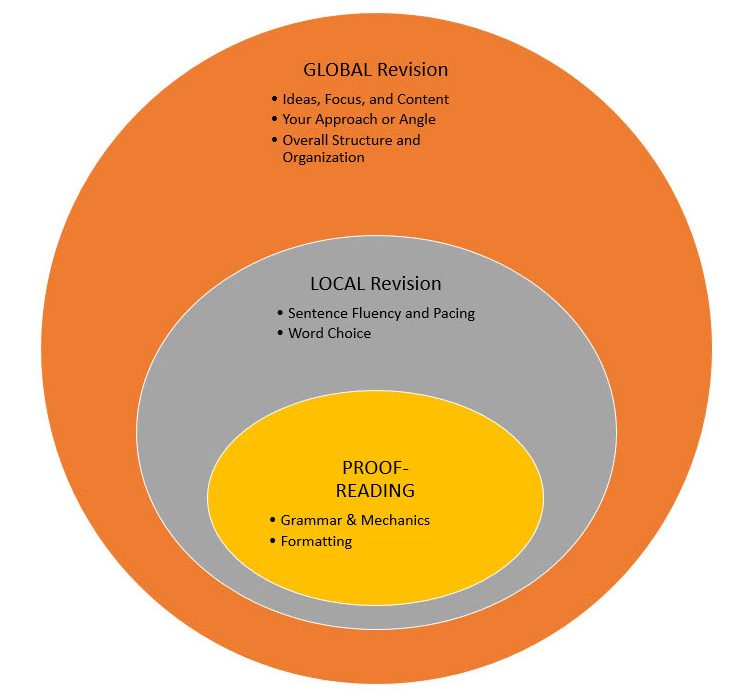

Revision isn’t just about polishing—it’s about seeing your piece from a new angle, with “fresh eyes.” Often, we get so close to our writing that we need to be able to see it from a different perspective to improve it. Revision happens on many levels. What you may have been trained to think of as revision—grammatical and mechanical fixes—is just one tier. Here’s how I like to imagine it:

Even though all kinds of revision are valuable, your global issues are first-order concerns, and proofreading is a last-order concern. If your entire topic, approach, or structure needs revision, it doesn’t matter if you have a comma splice or two. You’ll likely end up rewriting that sentence anyway. Fortunately, there are a handful of techniques you can experiment with to practice true revision.

First, if you can, take some time away from your writing. When you return, you will have a clearer head. You will even, in some ways, be a different person when you come back—since we as humans are constantly changing from moment to moment, day to day, you will have a different perspective with some time away. This might be one way for you to make procrastination work in your favor: if you know you struggle with procrastination, try to bust out a quick first draft the day an essay is assigned. Then you can come back to it a few hours or a few days later with fresh eyes and a clearer idea of your goals.

Second, you can challenge yourself to reimagine your writing using global and local revision techniques. You may have been taught that revision means fixing commas, using a thesaurus to brighten up word choice, and maybe tweaking a sentence or two. However, you might prefer to think of revision as “re | vision.”

Third, you can (and should) read your paper aloud, if only to yourself. This technique distances you from your writing; by forcing yourself to read aloud, you may catch sticky spots, mechanical errors, abrupt transitions, and other mistakes you would miss if you were immersed in your writing. Some students chose to use an online text-to-speech voice reader to create this same separation. By listening along and taking notes, she can identify opportunities for local- and proofreading-level revision.)

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, you should rely on your learning community. Because you most likely work on tight deadlines and don’t always have the opportunity to take time away from our projects, you should solicit feedback from your classmates, the writing center, your instructor, your peer workshop group, or your friends and family. As readers, they have valuable insight into the rhetorical efficacy of your writing: their feedback can be useful in developing a piece that is conscious of the audience. To begin setting expectations and procedures for your peer workshop, turn to the first activity in this section.

Good writing cannot exist in a vacuum; similarly, good rewriting often requires a supportive learning community. Even if you have had negative experiences with peer workshops before, give them another chance. Not only do professional writers consistently work with other writers, but students are nearly always surprised by just how helpful it is to work alongside their classmates. Everyone has something valuable to offer in a learning community. There are so many different elements on which to articulate feedback, you can provide meaningful feedback to your workshop, even if you don’t feel like an expert writer.

During the many iterations of revising, remember to be flexible and to listen. Seeing your writing with fresh eyes requires you to step outside of yourself, figuratively. Listen actively and seek to truly understand feedback by asking clarifying questions and asking for examples. The reactions of your audience are a part of writing that you cannot overlook, so revision ought to be driven by the responses of your colleagues.

On the other hand, remember that the ultimate choice to use or disregard feedback is at the author’s discretion. Provide all the suggestions you want as a group member, but use your best judgment as an author. If members of your group disagree—great! Contradictory feedback reminds us that writing is a dynamic, transactional action that is dependent on the specific rhetorical audience. You can always go to your instructor with questions.

Revision: Alive and Kicking

All this revision talk could lead to the counterargument that revision is a death spiral, a way of shoving off the potential critique of a finished draft forever. Tinkering is something we think of as quaint but not very efficient. Writers can always make the excuse that something is a work in progress, that they just don’t have time for all this revision today. But this critique echoes the point that writing is social and responsive to its readers. Writing is almost always meant to be read and responded to, not hoarded away.

A recent large-scale study on writing’s impact on learning supports the idea that specific interventions in the writing process matter more in learning to write than how much students are writing (Anderson et al.). Among these useful interventions are participation in a lively revision culture and an interactive and social writing process, such as talking over drafts and soliciting feedback from instructors and classmates.

Typically, when we define an essay (noun) as a short piece of writing on a particular subject. It might be more instructive to think about the essay (verb): to try, to test, to explore, to attempt to understand. An essay (noun), then, is an attempt and an exploration. Popularized shortly before the Enlightenment era by Michel de Montaigne, the essay form was invested in the notion that writing invites discovery: the idea was that he, as a layperson without formal education in a specific discipline, would learn more about a subject through the act of writing itself.

Extending the modern definition of writing more broadly to composing in any medium, revision is as bound to writing as breathing is to living. If anything, humans are doing more writing and revision today. Sure, some people call themselves writers and mean that it is part of their formal job title. But then there are the greater numbers of us who are writers but don’t label ourselves as such, the millions of us just noodling around on Facebook, YouTube, or Instagram. Facebook and Instagram have an edit feature on posts. Google Docs includes a revision history tool and our phones have autocorrect. We edit our comments and texts to clarify them; we cannot resist. Revision as writing is an idea that we should not abandon or trash—and it may not even be possible to do so if we tried.

There is no one correct way of writing and speaking.

Most people implicitly understand that the way they communicate changes with different groups of people, from bosses to work colleagues to peers to relatives. They understand that conversations that may be appropriate over a private dinner may not be appropriate at the workplace. These conversational shifts might be subtle, but they are distinct. While most people accept and understand these nuances exist and will adapt to these unspoken rules—and while we have all committed a social faux pas when we didn’t understand these unspoken rules—we do not often afford this same benefit of the doubt to people who are new to our communities or who are learning our unspoken rules.

By perpetuating the myth of one correct way of writing, we are effectively marginalizing substantial swaths of the population linguistically and culturally. The first step in combating this is as easy as recognizing how correctness reinforces inequality and affects our perceptions of people, and questioning our assumptions about communication, and the second step is valuing code-switching in a wide swath of communicative situations.

Additional Resources

There Is More Than One Correct Way of Writing and Speaking Copyright © 2022 by Anjali Pattanayak; Liz Delf; Rob Drummond; and Kristy Kelly.

Attributions

A Dam Good Argument Copyright © 2022 by Liz Delf, Rob Drummond, and Kristy Kelly is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter has additions, edits, and organization by James Charles Devlin.