5.2 Titles and Introductions

Titles

The title may seem inconsequential in the grand scheme of writing a lengthy paper. However, a good title can work in your favor by catching your reader’s attention and helping to stand out. Titles are an opportunity to control the interpretation of your essay. When publishing, a title that grabs attention and succinctly summarizes the topic performs better.

- Use a phrase that identifies the subject.

- Consider a title that also suggests the main claim, or thesis (see below, and see the section Thesis for more information)

- Remember that the title is the writer’s main opportunity to control interpretation.

- Be creative in coming up with a title, but consider your audience!

- Don’t use a phrase that could easily apply to all the other students’ essays, such as the number or title of the assignment.

Titles should be specific and clear, and the quickest path to this is composing a title that states your exact subject. If you can also hint at your thesis in the title, it becomes that much more effective. Examples:

- The Extinction of Bees

- Peer Review in Writing Classes

- Why We Need Fantasy Literature

- Video Games and Art

- Video Games Can Never Be Art

In academic writing, it is also common to have a two-part title that consists of (1) a vivid or curious glimpse of some aspect of the subject and (2) a straightforward statement of the subject. This is generally used for longer essays, such as those comprising more than 2,000 words. Examples:

- Hashtag I’m Fired: Employment in the Era of Social Media

- Sanity in the Eye of the Beholder: The Dynamics of the Unreliable Narrator in “The Tell-Tale Heart”

Remember that titles are an opportunity to control the interpretation of your essay. Consider how the titles of films do this: What is the film Forrest Gump about? Most would agree it’s about the life of Forrest Gump. But what would the common answers be if the title had been Me and Jenny? It would probably be called a love story, which it kind of is given that title. Or what if it had been titled Me and Lieutenant Dan? Then it would probably be a buddy picture about friendship, which would be given that title. Use this quality of titles to guide your readers’ interpretations.

Introductions

This paragraph is the “first impression” paragraph. It needs to make an impression on the reader so that he or she becomes interested, understands your goal in the paper, and wants to read on. The intro often ends with the thesis.

Audiences want a clear idea of what they’re about to get into, what to expect, and what is so interesting about it, so use the introduction to give all of this to them. The biggest issue seen in introductions is that they don’t say anything substantive. As a result, students frequently write introductions for college papers in which the first two or three (or more) sentences are obvious or overly broad.

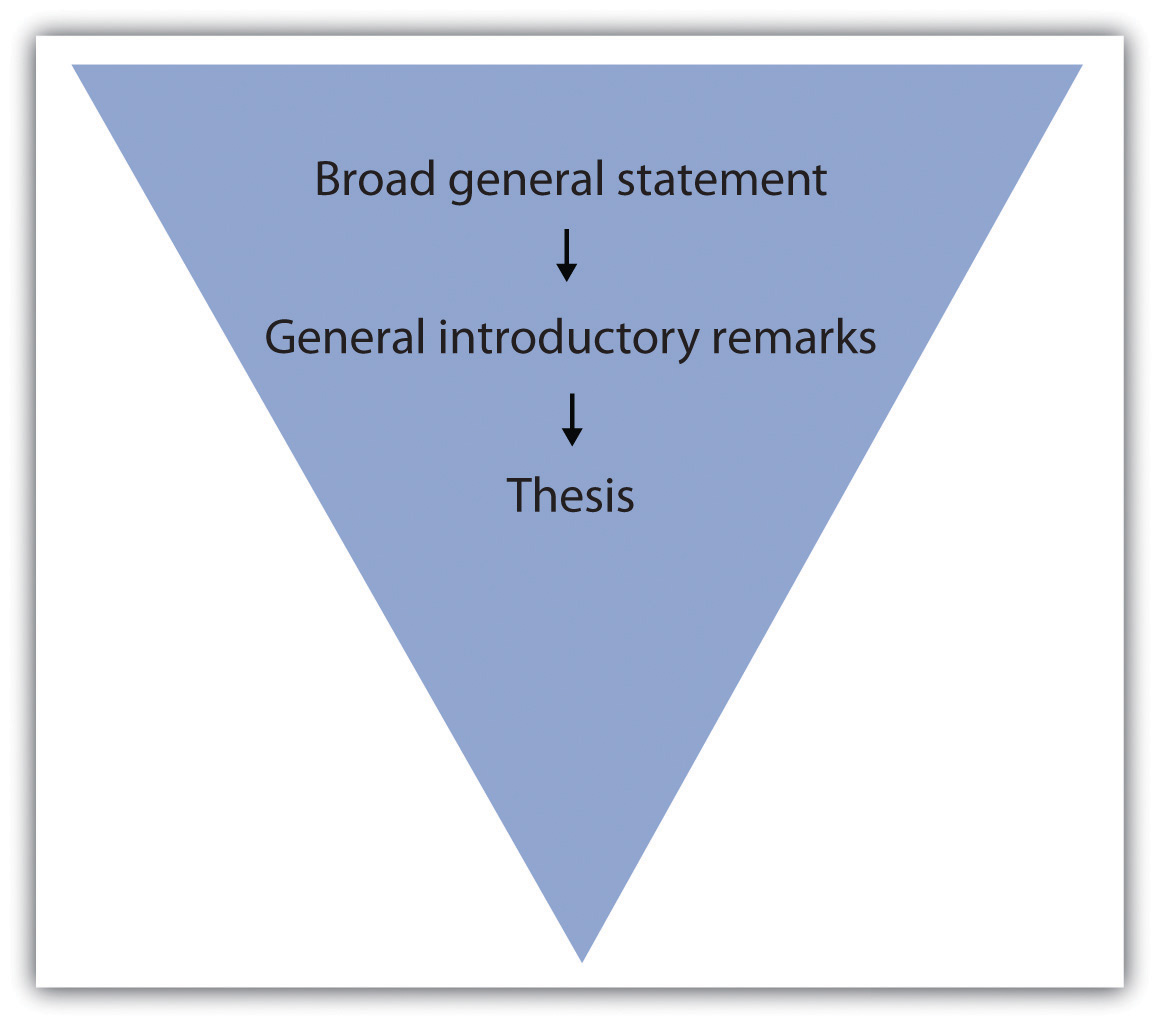

The most common strategy in an introduction is to move from the general context to a specific point. This often feels natural for writers and readers, so much so that we even see this kind of strategy in movies and shows: visuals of the whole city first, then of the one building, then of the specific room with the focal characters. In an essay, this works by first stating general facts or ideas about the subject. Then, as you move deeper into your introduction, you gradually narrow the focus, moving closer to your thesis. Moving smoothly and logically from your introductory remarks to your thesis statement can be visualized as a funnel-like structure, as illustrated in the diagram below:

Another strategy is to add something of specific and immediate interest right before this general context. This is done by employing the Classical advice of beginning in medias res, which means to start in the middle of things. Immediately offer a glimpse at a specific idea, example, or scenario that delves deep into a fascinating aspect of your subject, even if the meaning of it is not yet clear. In choosing this glimpse, consider what is surprising, counterintuitive, or vivid. This is often called “the attention grabber.”

That phrase is often misunderstood, for multitudes of student writers have written statements and questions that they find extremely boring, yet have told themselves they are doing so for the benefit of readers to “grab their attention.” The problem stems from assuming that readers are boring. They aren’t; they’re interesting, and they want to read interesting ideas. So bring up the interesting ideas. Don’t use false questions, such as those about the reader’s personal experience, those that have obvious answers, and those for which you won’t attempt specific or compelling answers.

After establishing this by beginning in medias res, you can then move to the first strategy noted above, moving from general context to a specific point, which in this case means explaining the subject you just introduced. Essentially, this is giving a larger understanding of what you mentioned above, such as what the important issue is or why it is significant. Don’t get detailed here; save details for the body paragraphs.

Building an Introduction Paragraph

Your first sentence should act as a hook. This sentence should pique the reader’s interest. This could be a memorable quotation, a relevant statistic, or a strong statement. As seen above, starting with a question can be seen as redundant and cliché.

- Begin by drawing your reader in: offer a statement that will pique their interest in your topic

- Immediately offer a glimpse at a specific idea, example, or scenario that delves deep into a fascinating aspect of your subject. This is often called “the attention grabber.”

- In choosing this glimpse, consider that which is surprising, counterintuitive, or vivid.

- Don’t use false questions, such as those about the reader’s personal experience, those that have obvious answers, or those for which you won’t attempt specific or compelling answers.

Next, it’s important to give context that will help your reader understand your argument. This might involve providing background information, giving an overview of important academic work or debates on the topic, and explaining difficult terms. This section would be the bulk of your introduction paragraph, and it should present information that will come up later.

- Context: Explain the subject you just introduced.

- Give a larger understanding of the glimpse above, such as what the important issue is, or why it is significant.

- Don’t get detailed. Save details for the body paragraphs.

One of your last sentences should make your main idea clear. That would be your thesis statement. Your claim should take a position or make a point about the subject, often by confirming or denying a proposition. Remember not to use a question or a fragment as a thesis, for those do not state points. Also, make sure to state your exact position on the subject, which is what a claim or thesis is, rather than simply stating the subject.

- Main Claim or Thesis: State the main claim or thesis of your entire essay in a single sentence.

- Your main claim or thesis is your position or point about the subject, often confirming or denying a proposition.

- For more details on thesis statements, see the section Thesis.

- Don’t use a question or a fragment as a main claim or thesis.

- Don’t confuse the subject with the main claim or thesis.

After you have made your claim or thesis clear, offer an essay map or a road map. This is the strategy of briefly naming the main points of the paragraphs to come, stating them in the same order that they will be used in the body of the essay. Avoid referencing your essay or your assignment, as with phrases such as “in this essay,” or “for my assignment,” or “I will discuss.” Instead, state your main points by discussing the subject itself rather than by discussing yourself writing it or the essay that contains it. Remember not to get detailed here either; save the details for the body paragraphs.

- Essay Map: Briefly name the three or more main points of the paragraphs to come, using the same order.

- Don’t reference your essay. State your main points by discussing the subject itself rather than by discussing the essay you’re writing.

- Don’t get detailed here either.

Attributions

The Writing Textbook by Josh Woods, editor, and contributor, as well as an unnamed author (by request from the original publisher), and other authors named separately is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter has additions, edits, and organization by James Charles Devlin.