Internet Sources

Most modern research begins with a quick internet search. However, please consider the wisdom imparted in this popular meme:

Most, if not all, sources found online will require further review and careful consideration before accepting that source as legitimate enough to cite within the presentation.

Domains

Some people hold the misconception that a website’s domain (the letters that follow the “dot” such as .com, .org, .edu, etc.) provides clues as to whether they may deem the information credible or not. In 1985, the world saw its first .com domain, Symbolics.com. At that time, the internet consisted of six top-level domains: .com, .org, .mil, .gov, .edu, and .net. During this period, for-profit corporations received the .com designation, non-profit organizations reserved .org, federal and state government entities used .gov, military branches seized .mil, higher education institutions claimed .edu, and .net generally applied to networking purposes only, such as email servers or internet service providers.

However, as the internet began to expand rapidly around 1991 and beyond, many of these protocols did not get enforced, especially for individuals or organizations wishing to register a website with a .org domain. Today, any person (without accountability or oversight) can register for a .com, .org, or .net domain, while .gov, .mil, and .edu face far more regulatory oversight. A vast array of top-level domains has sprung up, almost as a cottage industry. Nearly every country has their own unique domain (.ca, .jp, .uk, etc.). Other domain types include topic, interest, and industry-specific domains (.cloud, .link, .club, .bike, .hotel, .church, etc.) and ones aimed toward developing interpersonal relationships (.family, .dad , .home, .mom, etc.).

www.martinlutherking.org serves as an example of why the domain should not serve as a primary factor in determining the credibility of a website. In 1995, Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and leader of the controversial white supremacist group Stormfront Don Black purchased the rights to this website, along with mlking.org and mlking. com. Since then, Stormfront has resisted repeated attempts by other parties to take over the domain, both through court action as well as through outright purchase, and instead, continues to present information such as stating that the renowned civil rights leader had, in fact, lived his life as a drunken philandering con-man. It also proposed that the federal government appeal the holiday marking King’s birthday. Students using information from this site without carefully verifying or vetting the information by checking sources could end up facing a hostile audience due to the presentation of grossly inaccurate and factually incorrect information.

Who Runs the Site?

To vet such information on common websites, look for links marked as “About us” or “Hosted by ______ .” Explore those links, for they usually take the viewer to at least a brief paragraph explaining the mission of the organization and why they exist. Some authors who work for news organizations such as Huffington Post or Time, have hyperlinks embedded in their bylines to help provide access to additional information. Often, if the author appears to push an agenda, performing a quick internet search on that author’s name will return enough information to make an educated decision as to whether or not the person should become a credible source in the speech.

What Ads Populate the Site?

In addition to vetting the author(s), observe the products that get advertised on the site.

Quick caveat: In many cases an individual might see automatically generated ads based on cookies stored on her or his computer. A cookie represents a small piece of data sent by a website that gets stored in a user’s web browser while the user browses the internet. Every time the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the server to notify them of the user’s previous activity on that site.

The ads permanently loaded to the specific site reveal a lot about the values and stature of the organization presenting the information on the site. As the old saying goes, “money talks,” which means that advertisers pay revenue to the owner of that site for the opportunity to place their message amid the site’s information, and as a result, depending on the revenue, an advertising company could easily sway the owner of the site to alter the tone or content of said information.

How Old Is the Information?

Next, evaluate the age of the information presented on the site, particularly if dealing with date-sensitive information, such as technology-related topics. The following student account demonstrates the importance of checking the timeliness of information:

I was in a class my senior year, called Communication Consulting. In this class, we split into groups of four students each, and each group had to present a different consultation project summary. A group got up to speak before mine, and their topic was “How to handle yourself at an international business dinner.” One of the students in their group was covering people from Eastern Europe and their customs, and as she started speaking, she said something that struck us all as odd: “First thing you guys need to know is that you never want to call them Russians, as they prefer to be called Soviets.” Everyone in the audience started looking around at each other in disbelief, but she continued: “Also, don’t talk about the Iron Curtain, the arms race, or Communism. Instead, talk about topics like Glasnost or Perestroika.” Our eyes widened, because at that moment, we knew she was serious. We knew she was using some pretty sketchy information. Everyone started looking at our professor, whose face was turning redder by the minute. At the end of their presentation, the prof asked to see her sources, at which point, he pulled one of them up on the big screen, in front of the whole class. Imagine her shock when he pointed out that one of her sources, on the Soviet Union, was a snapshot of the World Book Encyclopedia from 1983!

The student in this example failed to look for a date reference of any kind, and instead, accepted everything she read as contemporary fact, and in the end, she ended up feeling humiliated in front of her peers. Always check for a date. Consider moving on to another source that includes one if unable to find one.

Wikipedia

No conversation about research would seem complete without discussing Wikipedia, which happens to commonly rank #1 in search results regardless of the topic of research. The common argument against using Wikipedia as a research resource is that the site allows anyone to change information in any article at any time. This raises concerns that whatever information the site presents could be manipulated and false. While this holds some truth, it only presents a small fraction of what really goes on behind the scenes of a Wikipedia article.

Hypothetical Case Study: “Asphalt Aaron” (loosely based on real events)

Hi, I’m Aaron, and to say that I am passionate about asphalt paving is an understatement. It is my life, my livelihood, and all I care about. You might suggest I need a better hobby, but I wouldn’t listen. One day, after work, I am surfing the web, looking up new and innovative advances in asphalt paving technology, when I decide to see what Wikipedia has to say about my passion, but lo and behold, there is no such article. Emboldened by this oversight, I take it upon myself to create one.

I then have to sign up to create the article in the first place, which presents very little difficulty, but then I have to learn the Wikipedia interface as a means to create my article and do it justice. Unfortunately, learning to create this article requires some advanced understanding of coding and programming lingo, but I am passionate about this, so I remain convinced that it is my duty to bring this article to life. Eventually, I learn my way around, craft a well-composed article on asphalt paving, and I submit it for publication.

At this point, the article goes to a volunteer editor at Wikipedia. Think, for just a moment, about the type of person who volunteers their time to edit articles for Wikipedia—for free. These people get aptly referred to as “grammar police” and they quickly point out inconsistencies and errors, so getting an article accepted by them could prove difficult. Many articles require source material to back up assertions, high quality writing, and uniqueness of topic to achieve publication, otherwise, they get swiftly deleted by these editors, who ultimately have the final say.

However, throughout a process of editing and revision back and forth between the editor and I, my article finally goes live. The next day, however, my mortal enemy, Concrete Chris, decides to play a cruel joke on me and edit my article to suggest that concrete paving has superior qualities compared to asphalt. He signs up, enters my article, and makes the edits, proud of his work to undo everything I have done. At that point, I receive an email notification telling me that someone has edited my pet project. Given the amount of time and effort put into my article, I likely would try to find a computer quickly to see the revisions. As soon as I see my nemesis’ writing, I can click a button to notify those same volunteer editors that I dispute the edit, at which point, my article reverts back to the last saved version prior to Concrete Chris’ edits while the site resolves the issue.

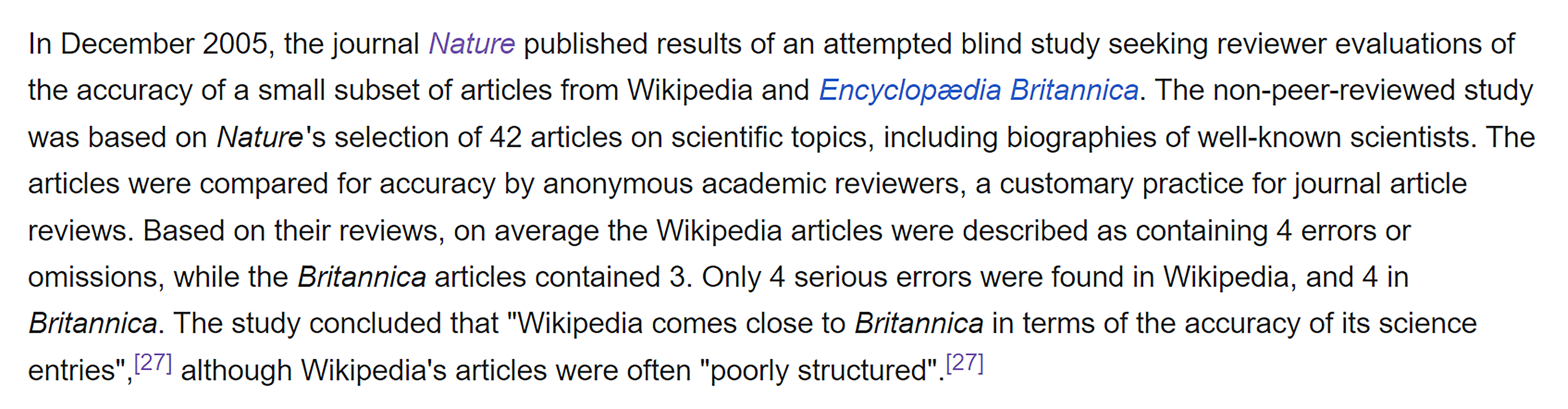

While anyone can edit a Wikipedia article, the process to do so remains rather rigorous and regimented. Although this does not equate to full accountability, this, combined with previous studies on the accuracy of Wikipedia that shows the site’s accuracy equals (if not exceeds) print sources such as Encyclopedia Britannica (Giles, 2005), demonstrates the validity of utilizing it as a research tool.

However, note that Wikipedia does not have an “author,” as the site provides access to an aggregate of information compiled by millions of individual authors. For this primary reason, never quote Wikipedia as a primary source. Doing so would be like reading a book from your college library, and then, in your speech, stating, “According to the library…”

Instead of referencing Wikipedia, browse the article’s sources cited within the entry. For example, take a look at the following excerpt from a Wikipedia entry on the reliability of Wikipedia:

Take note of the hyperlinked numbers in brackets. Clicking on that number takes the user to the following entry in the bibliography at the bottom of the article:

This represents the kind of information worthy of citation in a speech. For example, “According to a study conducted by the journal, Nature, in 2005…” However, take the time to verify the information and follow the trail to the original source, consume that information, and verify that the source truly says what the Wikipedia author contends. The last thing speakers should do is cite false or inaccurate information and end up with an audience member who knows this, for that person will immediately attempt to point out the flaw once the Q&A starts!

Blogs

Anyone can write a blog for any reason. They pre-date social media applications like Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, YouTube, and others, so many of them started as passion projects developed by people who wished to communicate their thoughts to the world. When conducting a web search with any search engine, dozens, if not hundreds, of blogs appear in the search results for nearly any topic or search string. Blogs can present a single person’s opinion, information from a scholarly journal of a researcher, or the output of a collection of like-minded individuals sharing their perspectives on a topic. Major news outlets like the New York Times, the L.A. Times, and others, have blog sections in their publications where knowledgeable journalists and credentialed individuals share their opinions on a subject or present deeply researched current event information. Look carefully at blogs, just as with any website, to evaluate the accuracy, trustworthiness, and credibility of the author and the information presented before using it as a source. Key questions people should ask when evaluating blogs include:

- What kind of blog is it?

- What is the blog’s overall purpose?

- Did the blog list its credentials or contact information?

- Does the blog provide source citations and links to supplemental information?

- Is the blog current?

- Does the blog seem to present a noticeable bias by its usage of loaded rhetoric or selective facts?

- Does the information in the blog contradict information found in another source?

Note to Self

Blog Spotlight

Started by renowned attorney, Harvard Law professor, and Supreme Court advocate Tom Goldstein in 2002, scotusblog.com has become a highly respected comprehensive source for what happens at the Supreme Court. The blog contains commentary and analysis by credentialed and well-respected experts in the legal community. Attorneys, students, and professionals view the blog as a trusted resource.