Survey Research

Passive information collection works well in many cases, but sometimes a presenter wants to guarantee a successful speech. At this point, consider pursuing more active means of collecting data on the audiences. Accomplish this goal by conducting survey research.

Types of Questions

Survey questions come in the form of two general categories: open-ended and closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions have no definitive answers, allowing the survey respondents to answer with anything they see fit, such as “What is your favorite movie of all time, and why?” Closed-ended questions limit the number of responses a respondent may offer, such as either-or questions (yes/no, true/false, etc.), multiple choice questions, and scaled questions (“On a scale from 1 to 10, rate your knowledge of…).

Both question classifications yield specific types of results. Open-ended questions provide detailed information about each individual taking the survey, and as such, these questions may prove challenging to categorize due to the variety of responses they inspire. While the answers offer valuable information that might appear in the speech in order to tailor content to very specific members of the audience, they fail at providing a more basic snapshot of the audience as a whole. To fill this void, closed-ended questions work well. Limiting the number of responses to a question allows the speaker to more efficiently collect and analyze data about highly specific aspects of the topic.

Methods to Administer Surveys

In addition to question types, consider how to deliver, or administer, the survey to the audience, because each type of survey brings with it a different set of benefits and challenges.

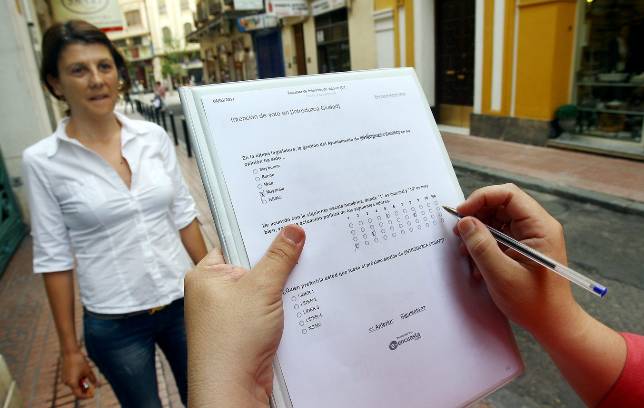

One of the simplest ways to conduct a survey is to deliver it face-to-face in a sort of informal interview approach. Write the questions out on a single sheet of paper, then approach people in the room, ask them the questions and record their responses. This cheap and relatively quick (depending on the number of questions asked) method comes with drawbacks. If any of the questions get remotely personal or invasive, meaning that they dig a little too deep, they may activate social desirability bias, or the tendency for most people to want to bend the truth ever so slightly on surveys to make themselves seem better than they actually are. For example, speakers including a survey question that asks respondents face-to-face how many illicit drugs they have tried in the last month can expect that most people will answer none, even though statistics suggest otherwise.

Another method of conducting a survey is to create a single sign-up or pass-around sheet that contains all of the questions, allowing each member of the audience to see how others before them have answered. While this provides an equally cost-effective solution as the previous example, it also may activate the social desirability bias. In addition, it adds the potential for groupthink, or the tendency for people to respond how the majority of others have responded before them, even if they don’t truly feel that way.

A third method employs technological means to create online surveys. A quick internet search for “free online survey tools” will turn up a wide variety of websites designed to create surveys effortlessly, before providing a link (URL) that the user can then email to everyone in the audience. Additionally, such survey tools provide free analysis options, allowing the speaker to automatically calculate a wide array of basic statistics (averages, distributions, percentages, etc.). Such surveys are quick to take, free to produce, and seem like they might offer the best option available, but they come with their own unique problems. Most notably: response rates are notoriously low. Most online survey websites tell their users up front to expect response rates of around 20–25%, so for every 20 people polled, expect that a mere 5–6 will respond. Sadly, this does not provide a very representative picture of the audience to assist the speaker.

The final option, the old-fashioned paper survey, may represent the best of all possible benefits. When speakers need to know as much as possible about their audience to effectively create an audience-centered speech, individual paper surveys present extensive benefits. First, depending on the length of the survey, one can copy and paste the same set of questions multiple times on a single page, thereby keeping printing cost to a minimum. Second, an individual paper survey provides anonymity and/or confidentiality to the survey-taker, thereby negating or minimizing the social desirability bias. Third, individual paper surveys, if handed out to a captive audience, capture the highest possible response rate by taking advantage of physical audience presence. While paper surveys require the survey-asker to tabulate and analyze the results, unlike the online survey method, it does capture a large sample, resulting in the best possible snapshot of the audience.

Survey Length

So how long should the survey be? The speaker’s topic should determine the appropriate length for the survey. Consider the number of questions needed for the following topics:

- Caffeine intake of college students

- Differences between political parties

- Depression and anxiety

The first topic might need, at most, 3–5 questions to determine the audience’s average weekly caffeine consumption. The second topic, however, has much more nuance and require up to 20 or more questions to determine the audience’s political views. While that may seem excessive, consider the third topic, which is so broad and complex it necessitates 100 or more questions (and likely a lot more time than one might have in a speech class) to accurately diagnose.

In addition to one’s topic, context plays a large role as audience demographics might determine how many questions seem appropriate. For example, if speaking to a group of first-grade children, asking five or more questions will likely tax their attention spans. Speakers may also want to consider the amount of time they have to deliver the survey, the size of the audience to survey, and the survey’s method of delivery. All these factors and more may require speakers to choose their questions wisely.